We live in a culture that often equates success with accumulation: more achievements, more possessions, more recognition. Yet many people discover, sometimes painfully, that climbing this ladder does not necessarily bring a richer or more satisfying life. The pursuit of self-actualisation asks a different set of questions. It is less about having more and more about becoming more.

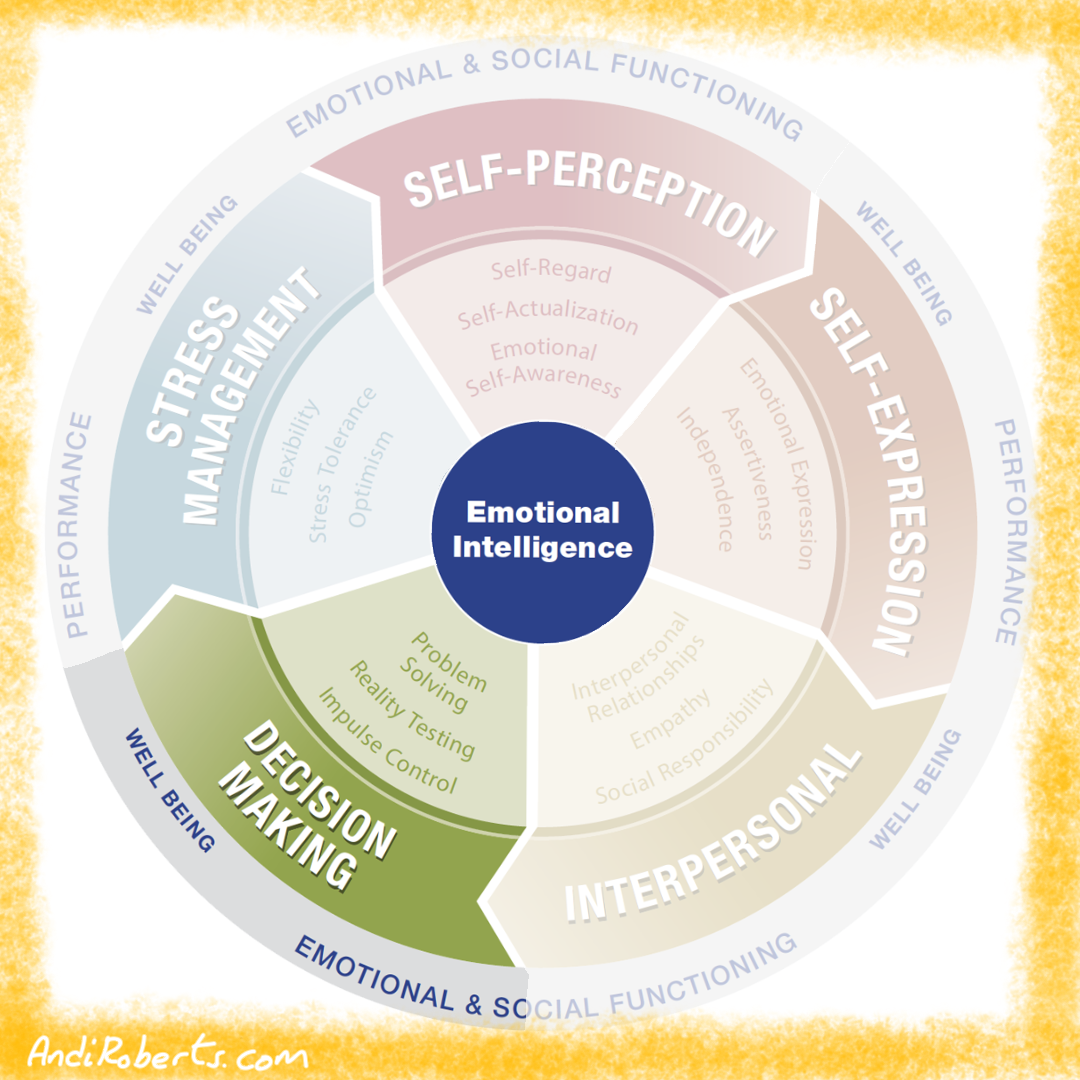

In the EQ-i model of emotional intelligence, self-actualisation is defined as the willingness to persistently improve oneself and to engage in the pursuit of personally meaningful goals that lead to a fulfilling life (Stein and Book, 2011). It is not a one-off achievement but an ongoing process of striving toward the fullest expression of one’s abilities, capacities, and talents.

Psychologists have long described this as one of the highest human motivations. Abraham Maslow (1943) placed self-actualisation at the peak of his hierarchy of needs, suggesting that once basic safety and belonging are met, humans yearn to grow into their potential. Modern research has expanded on this, showing that people who pursue personally meaningful goals report greater vitality, stronger resilience, and higher well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Sheldon and Elliot, 1999).

Self-actualisation is not about perfection or grand gestures. It is about daily choices that connect you to meaning. Choosing to pursue a passion project, to cultivate a strength, or to live in line with your values are all small but powerful steps. Over time, these choices form a pattern of life that feels coherent and satisfying.

Why self-actualisation matters

If self-actualisation is about living into your potential, the natural question follows: why does it matter? Why should we give energy to this lifelong pursuit?

Sustaining resilience

Life is filled with setbacks, changes, and pressures. When goals are rooted only in external approval, they crumble when recognition fades. Self-actualisation provides a steadier anchor. Research on self-concordant goals shows that when objectives are aligned with authentic values, people persist longer, recover more quickly from stress, and experience less burnout (Sheldon and Elliot, 1999). For example, a teacher driven by a deep value for fairness will find greater resilience in reforming classroom practice than one motivated purely by external rewards.

Enhancing decision-making

Self-actualisation sharpens the ability to choose wisely. When you know what matters most, you can filter opportunities and distractions more effectively. A leader who understands that creativity and sustainability are core values will choose projects that express both, even if they are harder in the short term. This clarity prevents the common trap of chasing achievements that look impressive but feel empty once gained.

Strengthening relationships

Pursuing authentic goals also influences how you connect with others. Leaders and colleagues who are anchored in self-actualisation often bring more integrity, openness, and energy to relationships. They are less threatened by feedback and more committed to shared purpose. Research on meaning-making shows that people who live with a sense of purpose foster stronger social bonds and communities (Steger, 2012).

Building fulfilment across time

Perhaps most importantly, self-actualisation creates a sense of coherence across a lifetime. Instead of experiencing success and failure as disconnected episodes, you begin to see them as part of a larger narrative of growth. You are not simply chasing milestones; you are shaping a story that reflects your values and potential.

The more profound truth is this: self-actualisation matters because it turns life from a series of tasks into a journey of meaning. It grounds resilience, sharpens choices, deepens relationships, and weaves your efforts into a coherent whole. Without it, you may accumulate achievements yet still feel a lingering absence. With it, even ordinary days become part of a rich and satisfying life.

Exercise 1: Values-to-goals alignment

Many of us inherit goals rather than choose them. We pursue promotions because others expect it, accumulate achievements because culture celebrates them, or follow routines because they are familiar. Yet goals that are detached from values rarely nourish self-actualisation. They may bring temporary satisfaction, but the energy soon fades.

Self-actualisation requires a deeper anchor. It is not the pursuit of success in general but the pursuit of meaningful success, goals that embody what you most care about. This is why values-to-goals alignment matters. It forces the question: Am I striving toward what is mine, or toward what belongs to someone else’s story of success?

Psychologists Sheldon and Elliot (1999) demonstrated that when people set self-concordant goals, objectives aligned with authentic interests and values, they reported greater vitality, less stress, and higher well-being over time. By contrast, goals shaped by external pressure often created strain and disengagement. In other words, when your goals express your values, striving feels like an extension of yourself rather than a performance.

This practice is not about rewriting your entire life plan in one sitting. It is about tracing the thread from what matters most, values, to what you are actively working toward, goals. Over time, that thread becomes a compass, allowing you to persist not because you “should” but because you genuinely want to.

Steps

-

Clarify core values. Choose three to five values that feel most central to who you are, such as creativity, fairness, learning, compassion. Write them down.

-

Name long-term goals. For each value, ask: What would it look like to live this value more fully in the next five years? Write a concrete aspiration.

-

Design short-term actions. Break each long-term goal into practical steps you can take this month.

-

Check alignment. Ask: Does this goal reflect my authentic values, or external pressure? Adjust until the link feels genuine.

-

Create accountability. Share one value-goal pair with a trusted colleague, mentor, or friend who can support you.

Examples

-

Workplace example: Creativity

-

Value: “I care about originality and expression.”

-

Long-term goal: “Within five years, I want to design a new product line that reflects sustainable design principles.”

-

Short-term action: “In the next month, I will set up one lunchtime brainstorm with colleagues on eco-friendly design.”

-

Effect: Instead of waiting for permission, the individual activates their value now, making creativity not a distant aspiration but a living practice.

-

-

Leadership example: Fairness

-

Value: “I care about justice and equity.”

-

Long-term goal: “Over the next three years, I want to make hiring in my department more inclusive.”

-

Short-term action: “This month I will review our job descriptions for unconscious bias and suggest revisions.”

-

Effect: A lofty aspiration translates into a small, tangible step that signals commitment to fairness.

-

-

Personal life example: Learning

-

Value: “I care about growth and knowledge.”

-

Long-term goal: “I want to become fluent in Spanish within four years.”

-

Short-term action: “This week I will download a language app and book one community class.”

-

Effect: The value of learning comes alive in a structured, achievable path.

-

-

Family life example: Compassion

-

Value: “I care about caring for others.”

-

Long-term goal: “I want to volunteer regularly with a community health project.”

-

Short-term action: “I will call two local organisations this month and attend one orientation session.”

-

Effect: Compassion shifts from a sentiment into a consistent pattern of action.

-

Why it matters: Without alignment, goals can leave you busy but empty. You may achieve the promotion, finish the project, or tick the milestone, yet still feel the question lingering: Was this really mine? Misaligned goals often drain more than they give, because they require constant willpower without the deeper fuel of meaning.

When values and goals are aligned, striving becomes sustainable. Effort feels energising rather than depleting. Failures sting less because they are in service of something you believe in. Successes feel more satisfying because they reflect who you are.

In organisations, values-to-goals alignment creates employees who are not just compliant but committed. A manager who links their value of fairness to inclusive hiring practices is more resilient in the face of resistance. A designer who links creativity to sustainability finds renewed motivation in long hours of iteration.

On the personal level, aligned goals support a more coherent and fulfilling life story. Instead of living someone else’s script, you live your own. The deeper truth is this: self-actualisation is not about chasing more, but about choosing what matters most and persisting with it over time.

Exercise 2: The ideal day and week map

Self-actualisation is rarely achieved in grand gestures. It is lived in the shape of ordinary days and weeks. Yet many people drift into patterns dictated by deadlines, routines, or cultural expectations rather than by what genuinely nourishes them. Over time, this drift can leave life feeling busy but not fulfilling.

The Ideal Day and Week Map brings your attention back to design. It asks two connected questions: What would a meaningful day look like? and How would a week feel if it reflected my deepest values? Together these perspectives reveal both rhythm and balance. A single day shows the details of how you want to live, while a week shows the wider composition of your commitments, relationships, and renewal.

Research supports this approach. Studies of “possible selves” show that when people create vivid images of the lives they want to live, they are more motivated and resilient in pursuing them (Markus and Nurius, 1986). Work on “mental simulation” shows that imagining a process in detail increases follow-through (Taylor et al., 1998). And research on work-life balance confirms that intentional time allocation across roles improves satisfaction and reduces stress (Greenhaus and Allen, 2011). The Ideal Day and Week Map integrates these insights into a practical reflection you can repeat as life evolves.

Steps: Part 1 – The ideal day script

-

Set the scene. Take 20 minutes in a quiet place with pen and paper.

-

Picture waking. Write what time you wake, how you feel, and what your morning looks like.

-

Describe purpose. Capture how you spend your productive hours, whether in paid work, study, creativity, or service.

-

Include relationships. Note who you spend time with and how those interactions feel.

-

Add play and rest. Record leisure, hobbies, or rest that bring joy.

-

Reflect on closure. Describe how you feel at the end of the day, and what makes you satisfied.

-

Highlight themes. Underline recurring values, such as learning, connection, or freedom.

Steps: Part 2 – The deal week map

-

Draw the framework. Sketch a weekly calendar with seven columns.

-

Block essentials. Mark fixed commitments such as work hours, caregiving, or classes.

-

Layer values. For each of your core values, ask: Where in the week does this live? Write in activities that express it.

-

Balance roles. Ensure time for work, relationships, self-care, growth, and contribution.

-

Check rhythm. Look at energy flow across the week. Are there recovery points after high-demand days?

-

Mark gaps. Circle values or roles that are missing and decide how to introduce them, even in small ways.

-

Choose one change. Identify a small experiment you can implement in the next week.

Examples

-

Professional example: An engineer

-

Ideal Day: Wakes at 7am, spends the morning on complex design projects, has lunch with colleagues, mentors a junior engineer, ends with exercise and dinner with friends.

-

Ideal Week: Three days of deep design work, one day dedicated to learning new tools, Friday afternoons mentoring or collaborating, weekend mornings for hiking and recovery.

-

-

Family life example: A parent

-

Ideal Day: Morning breakfast with children, part-time project work mid-morning, family time outdoors in the afternoon, evening reading once children are asleep.

-

Ideal Week: Work three school-day mornings, volunteer one afternoon, set aside Wednesday evenings as family game night, Sunday afternoons as extended family time.

-

-

Creative example: An artist

-

Ideal Day: Wakes early to sketch, works in the studio, shares lunch with peers, takes an inspiration walk, teaches an evening class.

-

Ideal Week: Four studio days, two teaching days, one day for community art projects and reflection.

-

Variations

-

Future focus. Write an Ideal Day and Week ten years from now, then compare with today.

-

Team version. Invite colleagues to share ideal workdays and weeks, then identify overlapping needs and redesign practices.

-

Micro-experiment. Adjust just one part of your week, such as creating an “ideal morning” or reclaiming Sunday evenings for renewal.

Why it matters: The Ideal Day and Week Map matters because self-actualisation is not an abstract idea. It is the lived reality of how you spend your hours. Many people postpone fulfilment, waiting for the right job, the right conditions, or the right stage of life. This exercise reminds you that you already have the power to shape meaning within your current days and weeks.

The day script shows what makes a single day rich and satisfying. The week map ensures that across time, you are balancing multiple values rather than living in a single dimension. When used together, they help you catch two dangers: the risk of living without rhythm, repeating days that feel hollow, and the risk of living without balance, pouring energy into one area while neglecting others.

In organisations, collective use of this exercise can surface cultural blind spots. If most people’s ideal weeks include uninterrupted creative time but their real weeks are fragmented, leaders have clear data for redesign. On a personal level, the practice helps you live more intentionally. Even small adjustments, like shifting a weekly meeting to protect a creative morning, can create ripple effects in energy and satisfaction.

The deeper truth is this: life is not made up of years but of days and weeks. If you can shape them with intention, you are already moving toward a self-actualised life.

Exercise 3: Signature strengths expansion

Many people approach growth by focusing on deficits. The question becomes, What is wrong with me, and how do I fix it? While addressing weaknesses matters, self-actualisation requires another lens: What is strong in me, and how can I bring more of it into the world?

The VIA Character Strengths framework provides this lens. Developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004), it identifies 24 universal strengths of character that cut across cultures and traditions. These strengths are grouped into six virtues:

-

Wisdom: creativity, curiosity, judgment, love of learning, perspective

-

Courage: bravery, honesty, perseverance, zest

-

Humanity: kindness, love, social intelligence

-

Justice: fairness, leadership, teamwork

-

Temperance: forgiveness, humility, prudence, self-regulation

-

Transcendence: appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humour, spirituality

Everyone possesses all 24 strengths, but to varying degrees. Signature strengths are those that come most naturally. They feel energising rather than draining, authentic rather than forced. Using them creates a sense of flow and meaning.

Research shows that applying signature strengths intentionally predicts higher well-being and life satisfaction (Park, Peterson, and Seligman, 2004). Even more powerful is using them in new ways. In one study, participants who applied a top strength in a fresh context each day reported lasting increases in happiness and reductions in depression (Seligman et al., 2005). The Signature Strengths Expansion exercise harnesses this principle by asking you to identify your top strengths, design new uses for them, and reflect on their impact.

Steps

-

Take the VIA Survey. Complete the free assessment at viacharacter.org and note your top five strengths.

-

Select one strength. Choose a strength that feels energising or especially relevant right now.

-

Design a new use. Brainstorm one way to apply this strength in a context where you do not usually use it.

-

Plan the action. Be specific about when and where you will try it in the next week.

-

Watch for the shadow. Every strength has a risk when overused. Write down what to avoid.

-

Reflect after use. Ask: How did this feel? What effect did it have on me and others? Did the shadow side show up?

-

Repeat with another strength. Over time, explore each of your top five.

Examples

-

Strength: Curiosity

-

New use: In a recurring staff meeting, ask two open questions rather than defaulting to answers.

-

Shadow: Curiosity may slip into distraction or endless questioning.

-

Reflection: “The questions sparked new ideas and kept me engaged, but I noticed I needed to stop myself from going off-track.”

-

-

Strength: Kindness

-

New use: Write a note of appreciation to a colleague you rarely interact with.

-

Shadow: Kindness can become overextension or rescuing.

-

Reflection: “The colleague felt seen, which built goodwill. I also kept it brief so I did not overcommit myself.”

-

-

Strength: Perseverance

-

New use: Apply steady effort to a neglected personal goal, such as finishing a book draft or learning an instrument.

-

Shadow: Perseverance may turn into stubbornness or ignoring fatigue.

-

Reflection: “I made real progress, but I also noticed I skipped breaks. Next time I will set time limits.”

-

-

Strength: Humour

-

New use: Open a tense client meeting with a light but relevant story.

-

Shadow: Humour may undermine seriousness if overdone.

-

Reflection: “The room relaxed, but I kept the story short so the tone remained professional.”

-

Variations

Option A: Balanced Strengths Practice

Top strengths can cause friction when pushed too hard. Perseverance can become stubbornness, honesty can feel blunt, kindness can drift into rescuing. Balance comes from pairing an overused strength with a complementary one, then practising both with intention.

Steps

-

Review your VIA results and circle one top strength you may overuse.

-

Choose a balancing strength that would counter the risk. Examples: prudence to balance honesty, self-regulation to balance zest, fairness to balance leadership.

-

Design two micro-behaviours: one guardrail for the overuse and one activation for the balancing strength.

-

Set an if-then plan such as “If I notice [trigger], then I will [guardrail or activation].”

-

Collect one piece of feedback from a colleague or partner.

-

Reflect on what changed in outcomes, relationships, and your energy.

Examples

-

Honesty → Prudence: Pause for three breaths before giving feedback.

-

Perseverance → Self-regulation: Use a 50-minute focus timer, then rest.

-

Kindness → Prudence: Check your diary before agreeing to help.

-

Leadership → Fairness: Hold back your view until two others have spoken.

Balanced Strengths Practice matters because it prevents your best qualities from backfiring. It helps you keep strengths useful under pressure and broadens your repertoire beyond a single identity.

Option B: Strengths Stretch Challenge

Self-actualisation is also about growth at the edges. By practising a strength that is less natural, you expand your range and discover new sources of energy.

Steps

-

Identify one of your bottom five VIA strengths.

-

Brainstorm one simple action to practise it for ten minutes a day over five days.

-

Anchor the practice to an existing routine such as morning coffee.

-

Track energy and usefulness each day on a scale from 1 to 5.

-

Reflect on what surprised you and decide whether to continue or rotate to another low strength.

Examples

-

Appreciation of beauty: Photograph one everyday scene and share why you value it.

-

Humility: Credit someone else’s idea before adding your own.

-

Bravery: Voice one concern early in a discussion.

-

Gratitude: Write a three-line thank-you note to a colleague.

-

Prudence: Before a decision, list two risks and one mitigation.

-

Teamwork: Ask “How can I help the group move this forward today?”

Strengths Stretch Challenge matters because it reduces over-reliance on a narrow set of traits and helps you grow in directions you might normally avoid.

Why it matters: Many development efforts stall because they are framed as repair work. Self-actualisation thrives when you build from strengths. Signature Strengths Expansion matters because it grounds growth in what is authentic, energising, and already present in you.

Balanced Strengths Practice prevents blind spots by pairing strengths with counterweights. Strengths Stretch Challenge widens range by cultivating capacities that are less natural. Together, these approaches ensure that strengths become not just habits but instruments of deliberate growth.

The deeper truth is this: self-actualisation is not about becoming someone else. It is about becoming more fully yourself, using your natural capacities with awareness, balance, and creativity. Signature Strengths Expansion helps you walk that path deliberately.

Exercise 4: Growth edge commitment

Self-actualisation is not only about living by values or enjoying passions. It also requires leaning into discomfort, because growth often begins at the edges of our current abilities. The “growth edge” is the zone where you feel stretched, challenged, and slightly vulnerable, yet still capable of progress. Too much comfort breeds stagnation, while too much stretch leads to overwhelm. The growth edge sits in between.

This practice helps you identify one meaningful area of stretch and commit to it deliberately. Instead of drifting into challenges by accident, you choose them in service of becoming more fully yourself. The psychologist Lev Vygotsky described this as the “zone of proximal development,” the space just beyond what you can already do, where learning is most alive (Vygotsky, 1978). Research on deliberate practice echoes this: skills improve most when effort is focused just beyond current competence, paired with feedback and reflection (Ericsson et al., 1993).

Self-actualisation is not achieved by repeating what is easy. It is realised through persistence in areas that matter but do not yet feel comfortable.

Steps

-

Name the edge: Ask: What challenge excites and unsettles me at the same time? Where do I hesitate, but know growth waits? Examples: public speaking, giving tough feedback, creative risk-taking.

-

Frame the purpose: Clarify why this edge matters to you. Connect it to a value or long-term aspiration. Example: “Public speaking matters because I value influence and want to share my research more widely.”

-

Design a small commitment: Break the edge into a manageable action for the next month. Example: “I will volunteer to give a five-minute update at the next team meeting.”

-

Seek feedback and support: Ask a trusted colleague, friend, or coach to observe and reflect back what they notice. Growth edges sharpen more clearly when seen with others.

-

Reflect and recalibrate: After the action, journal: What did I learn? What surprised me? What is my next step at the edge?

Examples

-

Leader

-

Growth edge: addressing conflict directly.

-

Purpose: fairness and trust.

-

Action: schedule one candid conversation with a team member about unmet expectations.

-

-

Student

-

Growth edge: sharing work publicly.

-

Purpose: creativity and courage.

-

Action: submit one piece of writing to the student magazine.

-

-

Parent

-

Growth edge: asking for help.

-

Purpose: balance and connection.

-

Action: call a friend to babysit instead of carrying the load alone.

-

-

Entrepreneur

-

Growth edge: pitching to investors.

-

Purpose: vision and contribution.

-

Action: rehearse with a mentor and deliver a short version at a networking event.

-

Variations

-

Stretch cycle: every quarter, choose a new growth edge. Review progress and set a fresh challenge.

-

Edge buddy: partner with someone else. Share your edge and hold one another accountable.

-

Micro-edge: if the stretch feels daunting, pick a micro-action, such as speaking up once in a small meeting rather than delivering a keynote.

Why it matters: Self-actualisation depends on momentum. If you only stay within comfort zones, your potential remains dormant. If you only face overwhelming challenges, discouragement follows. The growth edge provides the middle path: a deliberate stretch that builds both skill and confidence.

Research shows that people who engage in sustained, meaningful challenge report higher satisfaction and stronger learning (Dweck, 2006). Facing a growth edge also builds resilience, because you learn to tolerate discomfort without retreating. Over time, the repeated act of leaning into edges creates not only new skills but also a self-story of courage and persistence.

The deeper truth is this: to actualise yourself is to risk yourself. By stepping into edges, you show respect for your potential and trust in your capacity to grow.

Exercise 5: Passion project practice

Self-actualisation is not fuelled by obligation alone. While values and goals provide direction, joy and passion provide energy. Many of us devote nearly all of our time to responsibilities, deadlines, and the urgent demands of others. The result is that pursuits which bring vitality — painting, music, gardening, writing, volunteering, building something with your hands — are pushed aside as luxuries.

The paradox is that these so-called luxuries often carry the essence of self-actualisation. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990) called this state flow: the experience of being fully absorbed in an activity that stretches skill and sparks enjoyment. Flow activities replenish energy, build competence, and remind us of who we are beyond roles and obligations.

Passion projects are not limited to personal life. They can flourish at work too. A software developer may explore machine learning outside of immediate job tasks. A manager might pilot a small initiative on employee well-being. A nurse could research a quality improvement idea for patient care. These are not side hustles but expressions of curiosity and meaning within the workplace. When supported, they enhance engagement, innovation, and loyalty.

This practice is about reclaiming one of those pursuits as a “passion project.” A passion project is not a performance strategy. It is an activity that feels deeply your own, chosen for its meaning and enjoyment rather than external reward. By giving it space, even in small doses, you cultivate a richer and more sustainable path of self-actualisation.

Steps

-

Recall sources of passion

-

List activities, past or present, that have absorbed you so fully that time seemed to vanish. They might be creative, physical, intellectual, or relational.

-

Example: “Cooking elaborate meals,” “Fixing old bicycles,” “Writing stories,” “Practising the guitar.”

-

-

Choose one project

-

Select one activity that feels both exciting and realistic in your current life. This is not about doing everything at once, but choosing one door back into joy.

-

-

Frame it as a project

-

Define a shape and direction. Projects have a goal, however modest.

-

Example: “Prepare three new dishes over the next month” or “Write one short story in six weeks.”

-

-

Carve out time

-

Schedule dedicated blocks, even if only 30 minutes a week. Treat the time as non-negotiable.

-

-

Engage fully

-

When working on the project, turn off distractions. Let the activity absorb you.

-

-

Reflect on meaning

-

After each session, jot one or two sentences about what the project gave you — energy, insight, relaxation, or pride.

-

Examples

-

Engineer (workplace)

-

Passion project: exploring renewable energy solutions.

-

Goal: build a prototype of a solar-powered device within the next six months.

-

Outcome: deepened technical expertise and reignited excitement for problem-solving beyond daily project deadlines.

-

-

Teacher (personal)

-

Passion project: writing poetry.

-

Goal: complete a small chapbook of 20 poems within a year.

-

Outcome: regained a sense of personal voice, which enriched classroom teaching.

-

-

Manager (workplace)

-

Passion project: designing a peer-mentoring scheme.

-

Goal: pilot the programme in one department over the next quarter.

-

Outcome: created stronger cross-team collaboration and personal fulfilment through developing others.

-

-

Parent (personal)

-

Passion project: community garden.

-

Goal: plant a shared vegetable patch with neighbours this season.

-

Outcome: combined love of nature with connection, modelling sustainability for children.

-

-

Healthcare professional (workplace)

-

Passion project: researching new approaches to patient experience.

-

Goal: present findings at the annual staff development day.

-

Outcome: sparked departmental interest and built momentum for broader improvements in care quality.

-

-

Entrepreneur (personal/work blend)

-

Passion project: photography.

-

Goal: curate one exhibition of personal photos for colleagues and clients.

-

Outcome: rediscovered creative energy, strengthening both personal resilience and professional brand identity.

-

Variations

-

Micro-projects: choose something that can be completed in a week or even a day, such as composing a short song or baking a new recipe.

-

Collaborative projects: partner with a friend or colleague. Shared passion strengthens bonds.

-

Seasonal projects: align with natural rhythms, such as gardening in spring or hiking in autumn.

-

Passion sabbatical: once a year, dedicate a longer stretch (a weekend or week) solely to your project.

Why it matters: Passion projects feed the part of you that responsibility alone cannot reach. They provide renewal, build skills, and connect you with intrinsic motivation. Research on flow shows that engaging in such activities increases well-being and even enhances performance in other areas of life (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

At work, they are often the seedbed of innovation. Google’s famous “20 percent time” allowed employees to pursue personal projects, leading to products like Gmail and Google Maps. In smaller organisations, even modest encouragement, an afternoon a month for exploration, can unleash creativity and engagement.

In personal life, passion projects build identity beyond productivity. They remind you that worth is not only measured by output or role, but by the joy and meaning you bring to your days.

The deeper truth is that passion projects remind you that life is not only about striving toward distant goals, but also about inhabiting joy here and now. They are not distractions from self-actualisation. They are among its purest expressions.

Exercise 6: Contribution mapping

Self-actualisation is often understood as a personal journey of growth. Yet it also carries a relational dimension. We flourish not only by developing ourselves but also by seeing how our efforts contribute to something larger than us. A sense of contribution anchors self-actualisation in meaning.

Contribution can be subtle or grand. It might be mentoring a junior colleague, supporting a friend in crisis, improving a process at work, or advocating for a community cause. The common thread is this: you see that your actions make a difference. Research on meaningful work shows that people who connect their daily tasks to a broader purpose report higher engagement, resilience, and well-being (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997; Pratt & Ashforth, 2003).

The danger is that contribution often goes unrecognised. Many people underestimate the ripple effects of their behaviour, focusing only on outcomes tied to metrics or praise. Contribution mapping is a practice of deliberately tracing the ways, large and small, that your presence creates value for others. It shifts attention from What did I achieve? to How did I matter?

Steps

-

Choose a timeframe: Decide whether to reflect on a single day, a week, or a recent project.

-

List interactions and actions: Write down key activities you engaged in: conversations, meetings, tasks, or informal moments.

-

Ask the contribution question: For each, ask: What difference did this make for someone else? Look beyond outcomes to effects such as encouragement, clarity, or stability.

-

Note the ripple: Trace how the action may have extended further. Example: “By clarifying the plan for my team, I reduced their stress, which likely improved their focus with clients.”

-

Highlight themees: Identify recurring forms of contribution, such as bringing calm, sparking ideas, or offering empathy.

-

Name one forward intention: Choose one way to strengthen or repeat a form of contribution in the coming week.

Examples

-

Project manager (workplace)

-

Action: clarified meeting agenda.

-

Contribution: gave the team structure and confidence.

-

Ripple: enabled smoother collaboration with external partners.

-

Theme: clarity.

-

Intention: prepare agendas in advance for all major meetings.

-

-

Healthcare assistant (workplace)

-

Action: comforted a patient before a minor procedure.

-

Contribution: reduced fear in the moment.

-

Ripple: created trust that eased cooperation for the whole medical team.

-

Theme: reassurance.

-

Intention: continue to notice and name small moments of support.

-

-

Parent (personal)

-

Action: played a board game with child after dinner.

-

Contribution: fostered joy and connection.

-

Ripple: child went to bed more relaxed, improving family atmosphere.

-

Theme: presence.

-

Intention: protect at least two evenings a week for shared play.

-

-

Community volunteer (personal)

-

Action: delivered groceries to an elderly neighbour.

-

Contribution: provided practical help and reduced isolation.

-

Ripple: inspired neighbour to consider volunteering for others once recovered.

-

Theme: service.

-

Intention: expand involvement in neighbourhood initiatives.

-

Variations

-

Team mapping: in a group, invite each member to share one contribution they saw another bring during a project. This builds mutual recognition.

-

Micro-contributions: focus on small, often invisible acts such as listening attentively or sharing encouragement.

-

Visual map: draw contributions as nodes on a page, with arrows to show ripple effects. Seeing the web of impact can be illuminating.

Why it matters: Contribution mapping helps counteract a narrow focus on outcomes and achievements. It expands awareness of the many ways your actions create value, often in intangible but vital forms. This recognition strengthens motivation, reduces burnout, and fosters humility, you see that what matters is not only the big wins but the steady accumulation of small contributions.

At work, contribution mapping deepens engagement. Employees who connect their tasks to broader organisational or societal impact report greater satisfaction and persistence (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003). In personal life, it nurtures gratitude and belonging, reminding us that self-actualisation is tied to community as much as to individuality.

The deeper truth is this: self-actualisation is not simply about becoming your best self for your own sake. It is about bringing that self into relationship, so that others benefit too. Contribution mapping makes that link visible and invites you to live it intentionally.

Exercise 7: Legacy letter

Self-actualisation is not only about the present moment. It is also about the long arc of a life. One of the most powerful ways to clarify what truly matters is to imagine looking back from the future and asking, What do I hope my life stood for? This is the essence of the Legacy Letter.

The practice draws on the tradition of ethical wills, in which people write down lessons, values, and hopes to pass on to the next generation. In psychology, research on meaning-making shows that reflecting on long-term purpose increases resilience, motivation, and well-being (Steger, 2012). Writing a Legacy Letter helps connect today’s choices with tomorrow’s story. It shifts attention from immediate success or failure to the enduring values you want to embody.

This exercise is not about crafting a grand speech or perfect vision. It is about honesty. A Legacy Letter can be a single page that answers: What do I want to be remembered for? What values do I want to live by? What message would I give to my future self or to those I love?

By writing in this way, you anchor self-actualisation in meaning. Daily struggles take on new context when seen as part of a bigger narrative.

Steps

-

Set the frame: Imagine yourself many years in the future, looking back on your life.

-

Choose an audience: You might write to your younger self, your children, a close friend, or simply your present self.

-

Name your values: Write about the qualities you hope to have embodied. Examples: courage, kindness, fairness, creativity, love.

-

Describe the impact: Record the ways you hope those values influenced others.

-

Acknowledge imperfection: Include struggles or failures. Show how they shaped your growth.

-

Close with guidance: Offer a sentence or two of encouragement or advice to your present self.

Examples (shortened)

-

Professional life: “I want to be remembered as someone who combined clarity with compassion. I hope people will say I created spaces where ideas and people could grow. My failures taught me to slow down and listen.”

-

Personal life: “I want my children to remember that I showed up, even when I was tired or uncertain. I hope they will know that love and humour carried us through. My doubts became part of what made me steady in the end.”

-

Creative life: “I want to be remembered as someone who dared to make beauty, even when it was imperfect. I hope my work showed that courage is not the absence of fear but the willingness to keep creating.”

-

Leadership: “I want colleagues to say I built trust by being honest, even in hard times. That I stood for fairness and inclusion, and that my influence left people stronger, not smaller.”

Variations

-

Short form: Write a one-page version focused on three values only.

-

Audio or video letter: Record your legacy message as a spoken reflection.

-

Annual revision: Revisit the letter each year. Notice how your vision evolves with experience.

-

Shared practice: In a leadership retreat or family gathering, invite each person to draft and share a brief legacy statement.

Why it matters: Self-actualisation can easily collapse into chasing the next milestone. A Legacy Letter lifts your gaze. It reminds you that your worth is not measured by yesterday’s mistake or tomorrow’s promotion, but by the kind of person you are becoming across a lifetime.

Research in positive psychology shows that reflecting on meaning and long-term values supports well-being and strengthens resilience (Steger, 2012). Leaders who articulate legacy also lead with more integrity and long-term perspective, reducing the temptation to cut corners for short-term gains.

The deeper truth is this: self-actualisation is not only about what you do but who you are becoming. A Legacy Letter makes that truth visible and memorable. It becomes a compass you can return to when the path feels uncertain.

Exercise 8: Self-renewal rituals

Self-actualisation is a lifelong pursuit. It asks not only for ambition and persistence but also for sustainability. Without renewal, even the most meaningful goals become exhausting. Burnout, cynicism, and depletion are signs that self-actualisation has tilted into overextension. Renewal is not indulgence. It is the foundation that allows growth to continue.

Psychologist Stephen Covey (1989) described renewal as “sharpening the saw,” the practice of pausing to maintain and strengthen the very capacity that does the work. Research in recovery and resilience shows that deliberate rest, reflection, and replenishment increase creativity, well-being, and long-term performance (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Self-renewal rituals transform this insight into practice.

Rituals differ from routines. A routine is something you do regularly, like brushing your teeth. A ritual is charged with meaning. It reminds you of who you are and what you value. A morning walk can be routine, or it can be a ritual of gratitude if you use it to notice the beauty of the world. Renewal rituals embed meaning into ordinary actions, creating rhythms that keep self-actualisation alive across years.

Steps

-

Identify renewal sources: Reflect on what restores you: nature, music, prayer, physical activity, writing, solitude, connection.

-

Choose one rhythm: Decide where renewal fits best: daily, weekly, monthly, or seasonally. Example: daily journaling, weekly yoga, seasonal retreat.

-

Frame it as a ritual: Add intention or symbolism. Lighting a candle before journaling, saying a phrase of gratitude after exercise, dedicating a walk to reflection on one question.

-

Protect the practice: Treat it as non-negotiable, not something you squeeze in if time permits.

-

Reflect on its effect: After each ritual, ask: How do I feel now? What has been restored or clarified?

-

Adjust as life changes: Renewal rituals are not static. They shift as seasons and needs change.

Examples (shortened)

-

Leader (workplace)

-

Ritual: Friday afternoon reflection.

-

Practice: spend 15 minutes noting three contributions made and one learning from the week.

-

Effect: finishes the week with clarity, not just exhaustion, and enters the weekend with gratitude.

-

-

Healthcare worker (workplace)

-

Ritual: transition walk after each shift.

-

Practice: walk for 10 minutes outdoors before returning home. Use the walk to release the emotional weight of the day.

-

Effect: restores energy and prevents stress spillover into family life.

-

-

Parent (personal)

-

Ritual: evening gratitude circle.

-

Practice: each family member names one thing they appreciated about the day.

-

Effect: strengthens connection and models resilience through appreciation.

-

-

Artist (personal)

-

Ritual: seasonal retreat.

-

Practice: once every three months, spend a day in silence creating, reading, and walking.

-

Effect: renews inspiration and prevents creative burnout.

-

-

Entrepreneur (personal/work blend)

-

Ritual: Monday morning “vision reset.”

-

Practice: review long-term goals and ask how the week’s tasks serve them.

-

Effect: keeps daily grind connected to meaningful purpose.

-

Variations

-

Micro-renewals: weave 2–5 minute pauses into the day — a breath before a meeting, a short stretch between calls, a mindful sip of tea.

-

Communal rituals: create shared practices with teams or families, such as opening meetings with one moment of silence or ending the week with a shared appreciation.

-

Digital sabbath: designate one day or evening each week free of screens to reconnect with yourself and others.

-

Ritual of release: symbolically let go of stresses or failures — write them down and discard them, or share them with a trusted friend.

Why it matters: Without renewal, self-actualisation collapses under its own weight. People may begin with energy but lose vitality because they never pause to restore it. Renewal rituals create sustainable cycles: effort followed by replenishment, striving followed by rest, giving followed by receiving.

Research shows that deliberate recovery improves both well-being and effectiveness. Daily detachment from work predicts lower fatigue and higher engagement the next day (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Ritualising renewal also builds resilience: you know where to find stability when life’s demands grow intense.

The deeper truth is this: self-actualisation is not a sprint to a finish line. It is a way of living across decades. Renewal rituals ensure that the pursuit of growth does not consume the very self it seeks to fulfil. They create the conditions for joy, meaning, and resilience to endure.

Conclusion: Living into your potential

Self-actualisation is not a destination you reach once and for all. It is a way of living, a posture of growth, and a rhythm of aligning who you are with what you do. It is the willingness to keep stretching toward your potential while also finding joy in the process.

The eight practices in this article are not tasks to master or boxes to tick. They are invitations into a way of inhabiting your life more fully:

-

Values-to-Goals Alignment keeps your striving rooted in what matters most.

-

Ideal Day and Week Mapping helps you design rhythms that reflect your best self.

-

Character Strengths Activation invites you to live from your gifts with awareness of their shadows.

-

Passion Projects turn energy into action that nourishes vitality.

-

Learning Quests ensure you are always expanding your horizons.

-

Mentorship Mapping connects your growth to relationships that stretch and guide you.

-

Contribution Journaling grounds motivation in the difference you already make.

-

Self-Renewal Rituals protect the long arc of growth by building in recovery and replenishment.

Together, these practices form a cycle. You clarify what matters, design your days and weeks accordingly, activate your strengths, channel them into projects, keep learning, draw on mentors, celebrate your impact, and renew yourself along the way. When life changes, you repeat the cycle with fresh insight.

Self-actualisation is therefore not about perfection or permanent arrival. It is about persistence and presence. It is the ongoing commitment to growth, paired with the humility to rest, reflect, and recalibrate. It allows you to meet challenges with resilience, to pursue ambitions with clarity, and to savour the process as much as the outcomes.

Reflective questions

-

Which of the eight practices feels most natural to you right now, and which feels most uncomfortable? What does that reveal about your growth edge?

-

When you picture your ideal week, what small adjustments could you make tomorrow to bring it closer to reality?

-

Which character strength do you most want to activate in the coming month, and what shadow do you need to watch for?

-

What passion project or learning quest have you postponed that deserves attention now?

-

Who are the mentors, peers, or companions who can help sustain your pursuit of growth, and how might you reach out to them this week?

-

How do you currently celebrate your contributions, and what would it look like to do this more intentionally?

-

What renewal ritual, daily or weekly, could help you sustain your energy for the long journey of becoming?

Self-actualisation is less about achieving greatness and more about inhabiting your own potential with integrity and joy. Each practice is a doorway, and each doorway leads to the same destination: a life lived with purpose, energy, and dignity.

Do you have any tips or advice on self actualisation?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

References

Baumeister, R.F. and Leary, M.R., 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), pp.497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Brown, B., 2010. The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Center City, MN: Hazelden.

Dweck, C.S., 2006. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Edmondson, A., 1999. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp.350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Judge, T.A., Bono, J.E., Erez, A. and Locke, E.A., 2005. Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), pp.257–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.257

London, M. and Smither, J.W., 2002. Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Human Resource Management Review, 12(1), pp.81–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(01)00043-2

Maslow, A.H., 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), pp.370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Neff, K.D., 2003. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), pp.85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K.D., 2011. Self-compassion: The proven power of being kind to yourself. New York: William Morrow.

Peterson, C. and Seligman, M.E.P., 2004. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L., 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), pp.68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Seligman, M.E.P., Steen, T.A., Park, N. and Peterson, C., 2005. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), pp.410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Sheldon, K.M. and Elliot, A.J., 1999. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), pp.482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482

Sherman, D.K. and Cohen, G.L., 2006. The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, pp.183–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38004-5

Steger, M.F., 2012. Making meaning in life. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), pp.381–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2012.720832

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E., 2011. The EQ Edge: Emotional intelligence and your success. 3rd ed. Mississauga, ON: Jossey-Bass.

Wilson, T.D. and Gilbert, D.T., 2008. Explaining away: A model of affective adaptation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), pp.370–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00085.x

Leave A Comment