Modern leadership does not unfold in calm or predictable conditions. Priorities shift, demands stack, and expectations arrive faster than capacity can replenish. In this environment pressure is not an occasional spike. It is the normal texture of work. Stress tolerance is not about avoiding tension. It is the capacity to remain steady, clear, and relational when activation rises in the moment.

In the EQ-i model, stress tolerance is defined as the ability to withstand adverse events and stressful situations without falling apart by actively coping with stress rather than avoiding or being overwhelmed by it (Stein and Book, 2011). It is what enables a leader to stay connected to their thinking when the body is signalling urgency. Stress tolerant leaders are not less emotional. They are less hijacked. They maintain access to judgement while the nervous system is under load.

Without stress tolerance, even capable leaders lose presence. They react faster than they can think. They pursue certainty instead of clarity. They interpret challenge as threat and mistake urgency for importance. Over time, repeated micro-hijacks narrow emotional bandwidth, degrade decision quality, and create interpersonal friction. Pressure becomes a distorting force rather than an informational signal.

With stress tolerance, leaders keep agency inside intensity. They can hold tension without collapsing into fight, flight, or appease. They can stay in dialogue when criticised. They can maintain standards without turning to control. They experience stress but are not defined by it. Research in resilience and stress physiology shows that those who stay regulated during activation recover faster, think more flexibly, and protect long-term wellbeing (Bonanno, 2004; McEwen, 2007).

Stress tolerance also underpins other emotional competencies. It protects problem solving by preventing tunnel vision. It supports empathy by preserving the ability to listen while triggered. It strengthens impulse control by slowing the time between stimulus and action. It even safeguards reality testing by reducing the drift into catastrophic interpretation under load. Stress tolerance is not hardening. It is skilful contact with pressure.

Why stress tolerance matters

If stress tolerance is the capacity to function well while activated, why is it such a critical leadership capability? Because leadership does not happen when the world is calm. It happens when the stakes are non trivial and time is short.

Resilience under pressure: In uncertain and fast moving contexts, leaders face situations that stretch their skill. Stress tolerance allows them to stay anchored while intensity rises so they do not lose access to their best judgement.

Better decision making: Stress tolerant leaders can think while activated. They maintain cognitive flexibility and resist the pull towards premature closure or catastrophic interpretation. This protects quality of thought under strain.

Stronger relationships: Teams experience leaders not in their calmest moments but in their pressured ones. Stress tolerant leaders signal psychological safety by staying steady in conflict and challenge. Trust grows when pressure does not become aggression or withdrawal.

Within the EQ-i framework, stress tolerance is a foundational pillar of effective emotional functioning. It protects clarity, steadiness, and agency in moments where they are most easily lost. Developing stress tolerance is not about being unaffected by stress. It is about being effective while stress is present.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Stress tolerance refers to the ability to remain steady, cope effectively with pressure, and believe that one can manage difficult situations in ways that maintain movement and constructive engagement. High scores are not automatically better. When stress tolerance is underused, leaders can become anxious and reactive. When overused, they can become numb to risk, too relaxed, or insufficiently responsive. The continuum below illustrates how this composite typically looks at different levels of expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Uses ineffective coping mechanisms. |

Uses coping strategies that maintain control under pressure. |

Appears too relaxed even when urgency is required. |

|

Reacts quickly without intentionality. |

Remains calm and thoughtful when load increases. |

Does not notice or respond to overload signals. |

|

Anxiety drives decision making. |

Holds emotional steadiness without suppression. |

Is too calm and emotionally flat. |

|

Fear limits confident action. |

Adapts to change without becoming destabilised. |

Lacks appropriate urgency or momentum. |

|

Interprets pressure as threat rather than load. |

Treats pressure as a manageable condition. |

Avoids decisions and does not move situations forward. |

Balancing factors that keep stress tolerance adaptive and not passive

Stress tolerance is most effective when it is supported by complementary skills that keep calmness from becoming complacency. These balancing scales help leaders determine whether their steadiness is grounded purposefulness or simply disengagement.

Problem Solving: Effective problem solving converts emotional stability into productive action. Calm without problem solving simply becomes stillness. Calm combined with structured analysis turns pressure into progress. This scale provides the capability to act rather than simply cope.

Flexibility: Flexibility prevents stress tolerance becoming rigid detachment. Leaders with healthy flexibility can adjust their approach as circumstances shift. Calmness is no longer passive acceptance, it becomes an adaptable stance that keeps movement alive rather than fixed.

Interpersonal Relationships: Healthy relational engagement prevents stress tolerance from disconnecting the leader from others. Calm is helpful only if others feel understood and supported. When interpersonal connection is strong, calmness becomes co-regulation rather than silence or withdrawal.

Eight practices for strengthening stress tolerance

Stress tolerance grows through repeated exposure, conscious regulation, and deliberate recovery. Each practice in this section explores a different aspect of functioning well under activation: preparing before stress arrives, staying steady in the moment of intensity, and recovering quickly after the surge has passed so that strain does not accumulate.

Each practice follows the same structure:

- Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

- Steps to take guide you through the process.

- Examples show it in real contexts.

- Variations suggest ways to adapt.

- Why it matters grounds the practice in research and insight.

Stress tolerance, at its core, is the art of staying capable while activated. It allows leaders to meet pressure without losing clarity or becoming captive to urgency. When cultivated over time, stress tolerance turns load into workable ground and intensity into information rather than threat.

Capacity banking

Most people only think about coping once they are already overloaded. They wait until pressure is present before trying to regulate their reaction. By then, attention is narrow, options feel limited and the nervous system is already activated. Capacity banking reverses that sequence. It is the habit of accumulating resources before they are needed so that stress meets a well-prepared system, not a depleted one.

This approach is drawn from proactive coping research. It assumes that stress is not simply a function of load. It is a function of the relationship between demands and resources. When leaders invest in capacity ahead of exposure, they experience pressure as challenge rather than threat. They do not enter stressful moments empty-handed. They arrive with capability, support, time, and inner stability already in reserve.

Steps to take

1 – Identify upcoming stress exposures

Choose one or two situations in the next few weeks that will likely demand emotional steadiness or cognitive bandwidth.

Why: Anticipation primes the brain. When the mind sees stress as a future condition rather than a sudden ambush, fear and reactivity are reduced.

2 – Name the resource category

Decide whether you need skill, clarity, support, more physical energy, or protected time.

Why: This makes investment specific. Stress is lowered fastest when the resource built matches the nature of the demand.

3 – Take one small resource-building action

Block calibration time with a peer. Practise the skill. Book the preparation session. Organise expectations earlier.

Why: Banking capacity is not grand. It is incremental. Small actions compound into future composure.

4 – Remove one resource leak

Close an unnecessary meeting, clarify a boundary, or decline a low-value request.

Why: You build capacity not only by adding but by protecting what already exists.

5 – Review weekly

Ask yourself: “Are my resources rising or being eroded?”

Why: The review consolidates agency. Banking then becomes a habit, not a rescue manoeuvre.

Examples

A programme director knows that the next steering committee will include challenge and scrutiny. She books two short sense-check sessions with trusted colleagues to sharpen the story. When the meeting comes, confidence is grounded, not performed. Her nervous system is responding to familiarity, not threat.

A product manager anticipates a surge in stakeholder requests during a critical release window. She blocks protected focus time in advance and aligns expectations early with her sponsor. When the pressure arrives, she is working from surplus, not deficit.

A parent knows the school term ahead will include evening logistics and social demands. He reorganises routines, sets earlier bedtimes for the household, and pre-plans simpler weeknight meals. The period is still busy, but it is no longer chaotic.

A runner sees that a marathon training block will increase physical and emotional load. She proactively books sports massage, limits late-night screen time, and recruits a training buddy for support. When fatigue spikes, she draws on strength she has already banked.

Variations

Fast version: one future stressor, one resource, one small action.

Team version: end each week with everyone naming one resource they are banking for next week.

Energy version: choose one thing to stop this week to preserve capacity.

Strategic version: link capacity banking to quarterly goals.

Personal wellbeing version: bank physical energy before a heavy period.

Why it matters: Capacity banking changes the equation of stress. Demands do not shrink, but your ability to meet them expands. When the nervous system encounters pressure with preparation already in place, arousal does not spike so quickly. Leaders then experience more control, more choice, and more composure. They are not reacting to stress. They are drawing from reserves they built earlier. This is how stress becomes more tolerable. It becomes less of an emergency and more of a challenge.

The deeper truth: Stress is not just “what is happening”. Stress is the gap between what is required and what is available. When you bank capacity, you close that gap before the moment arrives. You are not simply getting better at absorbing stress. You are shifting the conditions under which stress occurs. Over time, this changes your relationship to pressure itself. You stop fearing what is ahead, because you have already invested in who you will be when you meet it.

Stress rehearsal

Stress tolerance does not grow by thinking about being calm. It grows by practising calm in the presence of stress signals. Stress rehearsal is the intentional practice of staying present inside small, controlled increases in physiological activation. Instead of avoiding discomfort until a high-stakes moment, you expose yourself to mild challenge so your nervous system learns to remain steady rather than reflexively tighten, rush or shut down.

This is not preparation in the strategic sense. It is conditioning in the somatic sense. It is closer to strength training than planning. When leaders practise staying regulated while activation is rising, their body learns that stress is not fatal, nor urgent, nor evidence of loss of control. The signal becomes information, not threat. They are not trying to eliminate stress. They are expanding their ability to function inside it.

Steps to take

1 – Pick a mild stressor

Choose a trigger that raises activation to a 3–4 out of 10 on your internal scale. Examples: opening a meeting with a clear dissenting view, making the first contribution in a senior forum, thirty seconds of cool water at the end of a shower, or a short elevator pitch to a peer. Define a safe boundary in advance: location, duration, and what “stop” looks like.

Why: Learning happens at the edge, not the cliff. Setting intensity and boundaries prevents overwhelm and turns exposure into deliberate practice.

2 – Stay with the wave

As activation rises, attend to three channels: body (tight jaw, heat in chest, flutter in stomach), emotion (apprehension, urgency), mind (fast thoughts, catastrophising). Name each briefly: “tight chest,” “rush,” “urge to fix.” Keep posture open, feet grounded, and eyes steady. Avoid self-judgement. You are observing, not evaluating.

Why: Labelling and posture cues keep you in contact with experience rather than fusing with it. Observation interrupts avoidance and begins to rewire reflex.

3 – Regulate deliberately

Choose a simple protocol and stick to it for the whole interval. Options: paced breathing at approximately 5–6 breaths per minute; grounding through the soles of the feet while feeling weight shift; soft focus by widening peripheral vision; or a cue phrase such as “steady and present.” Do not try to erase sensation. Aim to coexist with it.

Why: One consistent regulation channel teaches your system that activation can sit alongside agency. Chasing multiple tricks increases noise and fragility.

4 – Hold for a short interval

Set a timer for 10–30 seconds to begin. Keep attention cycling between sensation and your chosen regulation cue. If intensity climbs past 6/10, reduce duration or lighten the stressor next round. If it stays 3–4/10, extend by 10 seconds next time, never beyond what you can recover from quickly. End the interval on purpose, not by flinching.

Why: Time under controlled activation is the training stimulus. Ending deliberately encodes “I can exit by choice,” which reduces fear the next time.

5 – Recover consciously

After the interval, take three slow breaths, shake out the hands and shoulders, and do a brief neutral movement, like a short walk. Write one sentence: “What rose, what worked, what I will try next.” Schedule the next micro-session in your diary. Frequency beats intensity: aim for three to five short reps per week.

Why: Recovery consolidates learning and signals safety to the nervous system. Brief reflection extracts the skill from the moment. Repetition builds familiarity into resilience.

Examples

A commercial lead practises answering difficult questioning while rehearsing answers with a peer who deliberately interrupts and pushes. The goal is not to “win the argument” but to stay grounded while activation rises. Over time, spikes feel like weather rather than threat.

A product manager rehearses saying “I disagree” three times a week in meetings where the cost is low. The nervous system learns that tension can be voiced without harm. In real conflict, she is noticeably more composed.

A cyclist finishes training rides with thirty seconds of cold-water exposure. The goal is to breathe through shock without flinching. The body learns that sharp stimulus does not require panic.

A guitarist plays a short improvised solo at open mic nights where no one knows him. He practises staying present through shaky fingers and adrenaline. After several weeks, the physical sensations are familiar rather than destabilising.

Variations

Micro social version: share one stretching idea early in a meeting.

Cold version: 10–20 seconds of cold shower at the end of a warm one.

Cognitive version: rehearse one tough sentence each morning.

Rhythm version: three slow breaths before answering a challenging question.

Team version: normalise small stress drills at start of workshops.

Why it matters: Stress rehearsal trains the state, not the story. The nervous system becomes accustomed to activation and stops treating it as emergency. Instead of trying to remove stress, you are increasing your ability to operate well in the presence of stress. This reduces physiological debt. Leaders who have rehearsed activation are less hijacked by it. Their threat response is slower to ignite, and their recovery is faster.

The deeper truth: Stress resilience is not the absence of arousal. It is the ability to stay in contact with yourself while your body is activated. Stress rehearsal teaches this directly. You are proving to yourself that you can remain a participant rather than a passenger in your own physiology. Over time, this becomes liberation. Stress becomes a state you can inhabit, not a state that owns you.

Steady state breathing

Stress tolerance is not the same as stress removal. Even highly experienced leaders confuse these two. They try to think clearly while their physiology is in full defensive mode. In those moments the nervous system has already moved into protection and thinking cannot lead. State always precedes story. When the body is in a stress cascade, the prefrontal cortex loses bandwidth, assumptions narrow, and urgency overrides choice.

Steady state breathing is the fastest manual lever to reverse this sequence. By shaping breath into a slow, even rhythm of approximately five seconds in and five seconds out, the cardiovascular and respiratory systems move back toward coherence. When physiology steadies, cognition becomes usable again. This technique is not about deep calm or relaxation. It is a practical way to regain decision capable presence in the middle of pressure, not after it.

Steps to take

1 – Establish the rhythm

Inhale gently through the nose for five seconds. Exhale slowly for five seconds through soft lips. This is the whole method.

Why: Equal pacing of inhale and exhale engages the vagus nerve which interrupts rising arousal. The rhythm drives the state.

2 – Release facial tension

Soften the eyes, relax the jaw, loosen the tongue.

Why: Facial muscles are direct inputs into the brainstem. When the face relaxes, threat cues reduce and the body stops bracing.

3 – Breathe from the lower ribs

Place attention low, not in the upper chest.

Why: Diaphragmatic breathing lowers panic chemistry. Upper chest breathing amplifies adrenaline and confusion.

4 – Maintain the rhythm for 60 to 90 seconds

Commit to the pattern without trying to reduce sensation.

Why: The goal is not to remove activation. It is to restore coherence so higher function becomes available again.

5 – Return to action with one intentional move

When the minute is complete, speak one line or ask one clear question.

Why: Behavioural re entry seals the reset. Agency is strengthened through action, not stillness.

Examples

A head of strategy is challenged mid presentation. She keeps her face neutral, shifts to five five breathing while others speak, and replies with one specific clarifying question rather than defending her stance.

An engineering lead notices that his throat is tightening during a technical argument. He quietly moves into the rhythm while watching the slide on screen. The spike passes and he contributes with steadier tone.

A parent feels pressure rising during a school drop off argument. He steps two metres back, breathes five five for a minute, then returns and names one simple next step for the child.

A runner feels panic rising when pace slips. She breathes five five, relaxes her jaw, shifts attention to her lower ribs, and regains form.

variations

Portable: use steady state rhythm while someone else talks

Covert: hands still on the table and only breath is adjusted

Movement: breathe five five while walking a corridor

Team version: open a tense virtual meeting with 60 seconds of steady breathing in silence

Why it matters: Steady state breathing restores decision quality in the moment. It stops the nervous system from cascading into tunnel vision, defensive tone, or impulsive reaction. It is fast, portable, invisible and learnable. Leaders who can regulate during pressure are less likely to commit the errors that come from urgency rather than clarity.

The deeper truth: Stress tolerance is not the absence of activation. It is the ability to stay connected to intention while your body is alert. Steady state breathing is one of the most direct ways to do this. You are not avoiding stress. You are retaining choice inside it.

Pressure labelling

One of the fastest ways stress takes control is through fusion. The moment something feels threatening, the mind and body collapse into a single frame: “this is bad” or “this is personal” or “this is me failing.” Labelling pressure interrupts that fusion. When we name the stress response directly, we separate sensation from interpretation. The stimulus remains, but hijack does not. The act of putting language to the state recruits regions of the prefrontal cortex and gives the nervous system a chance to move from reflex back toward choice.

This is not about positive thinking and it is not a cognitive trick. It is a micro recognition skill that converts intensity into data. Leaders who practise pressure labelling do not deny discomfort. They locate it, name it, and then engage with it as information instead of identity.

Steps to take

1 – Catch the moment of surge

Begin by noticing the micro signs that activation is rising. It might be a sudden drop in breath, a flush of heat in the chest, faster speech, or a feeling of urgency to respond immediately. For example, a leader who feels their voice getting sharper in a negotiation can use that shift as the moment to intervene.

Why: Most hijack happens in the two seconds before we realise it. The earlier you recognise the lift in activation, the more agency you preserve.

2 – Name it in plain language

Once you detect the surge, silently name it with a very simple phrase such as “this is pressure” or “activation is here.” Keep it short so it feels like a label not a sentence. A team lead who hears their heart rate climb when a timeline is challenged could internally say “pressure now” while maintaining eye contact.

Why: The act of naming shifts processing from limbic automaticity toward prefrontal control. Naming is a form of neural distancing that interrupts reflex.

3 – Keep the label literal not interpretive

The temptation under stress is to instantly attach meaning. Phrases like “I am failing” or “they do not trust me” collapse sensation into identity. Avoid this. Keep the label strictly factual. For example, when a senior product manager feels their stomach tighten in a tough board Q and A, the correct label is “activation present” not “I am losing credibility.”

Why: Literal labels reduce threat because they do not attach narrative to sensation. Interpretive labels reinforce danger and accelerate emotional flooding.

4 – Stay with one line only

Do not upgrade your phrase or expand it into commentary. Hold the same short line for at least two slow breaths. When a head of sales notices herself beginning to speed up in a tense forecast review, she may silently repeat “pressure here” twice while breathing normally.

Why: Single-line repetition prevents rumination. Rumination invites collapse. Clarity stabilises.

5 – Proceed with one grounded action

Complete the sequence by taking one deliberate small behaviour. Ask one clarifying question, request one piece of information, or say one sentence that advances the conversation. For example, a delivery manager who has just labelled pressure might ask “Which part of this assumption worries you most?”

Why: Behavioural follow through seals the shift into agency. Stress tolerance is strengthened by doing not by pausing.

Examples

A senior account manager feels heat rise in a client escalation call. She silently says “pressure here” and keeps eyes soft. She then asks one precise clarifying question before responding.

A CTO hears that her launch date will slip. Thoughts rush. She names “activation present.” That phrase stops the mental tailspin and she can pivot into negotiation rather than defensiveness.

A parent feels irritation spike when a child spills juice just before leaving the house. He pauses and says internally “pressure here.” Tone softens. They clean up together without sharpness.

A pianist loses tempo during a live recital. Instead of chasing the mistake, he names “activation is rising” and returns to phrase shape rather than panic.

Variations

Physical anchor version: say the phrase while placing both feet evenly on the floor

Hand cue version: lightly pinch thumb and forefinger while naming the state

Post it version: keep the phrase “pressure here” on the corner of laptop screen

Team cue version: agree one shared phrase in project reviews to normalise tension as information

Why it matters: Pressure labelling converts stress from subjective overwhelm into objective signal. The brain works better when intensity is classified rather than swallowed. It interrupts limbic dominance and enables deliberate response rather than rushed reaction. The difference in practice is often just three seconds but that three seconds can decide whether someone snaps or stays intentional.

The deeper truth: Stress tolerance is not the elimination of pressure. It is the ability to recognise pressure without becoming it. Labelling gives leaders a vocabulary for state. Once you can name what is happening, you can choose how to move next. This shift is subtle but profound. Stress stops being a verdict and becomes information.

Stress fingerprinting

Escalation rarely begins at the moment we notice it. In most cases the stress cascade began several seconds earlier. The body signalled subtle micro shifts long before the mind registered threat. Leaders often believe pressure appears suddenly, but in practice the nervous system always whispers before it shouts. The challenge is that we are not listening to the right frequency. We are busy with task, logic, content and pace. Stress fingerprinting is the work of tuning perception to these faint early signals in real time so the moment remains influenceable rather than runaway.

Every person has unique pre spike cues. Some tighten the jaw. Some narrow peripheral vision. Some harden the voice. Some lose fine detail focus and go abstract. Some over speak to regain control. Some go mute. These are physiological signatures, not character flaws. When you know your fingerprint, the moment of escalation becomes visible earlier and therefore interceptable. Instead of discovering pressure after you are already in limbic hijack, you see it at the point of lift. This is the difference between reacting and steering.

Steps to take

Step one: commit to micro signals

Begin a live interaction and tell yourself that your job is not to manage the other person but to listen for your own earliest physical change. For example, notice when your heel lifts slightly, when your tongue presses the palate, when your blink rate changes, or when your breath shifts shallower. Choose one or two micro channels only.

Why: The body presents the first reliable data. Attention to micro physiology is the only way to see the rise before it becomes overwhelming.

Step two: call the cue in real time

As soon as you detect a micro signal, internally mark it. Use a simple mental label such as tight jaw or narrowing focus. Keep it strictly literal. Keep it short.

Why: The act of internal marking shifts the moment into conscious processing. Now you are in contact with the shift rather than fused with it.

Step three: stabilise posture not content

Hold posture baseline steady. Unclench hands. Let shoulders drop. Place both feet flat. You are not fixing content yet. You are stabilising your instrument.

Why: Posture is the backbone of state. A grounded body makes grounded behaviour possible. If you try to fix content while physiology is peaking you lose agency.

Step four: introduce one small anchor

Use one single steadying mechanism. One slow exhale. One foot press into the floor. One fraction slower sentence. Maintain only that one.

Why: Anchoring creates a hinge. The hinge separates moment from spiral. If you choose multiple anchors, you amplify noise not stability.

Step five: act minimally forward

Speak one clarifying question. Request one repeat. Or offer one short sentence. That small forward behaviour prevents stalling and rumination.

Why: Small forward movement reintroduces agency. Agency is the reset. You have not removed stress. You have reclaimed orientation within it.

Examples

A CFO notices that in tense board questions his breath thins. He monitors exhale length as he speaks. The longer breath holds his thinking open long enough to choose a better response rather than rush to defend.

A project director recognises that when challenged he locks shoulders. In the next difficult meeting he drops shoulder tension deliberately and asks one short clarifying question before responding. The question slows the spike.

A parent senses jaw tension rising when siblings argue. He softens jaw deliberately, takes one longer exhale and asks each child to repeat their last sentence instead of escalating.

A violinist notices her fingers stiffen during difficult passages. At the first sign she loosens grip and breathes slower for two bars. Mistakes reduce not because anxiety is gone but because she did not let the spike take over.

Variations

Sensory channel version: detect only breath or only jaw for an entire week

Cognitive version: detect when narrative speed increases

Social version: ask a trusted colleague to tell you what early signs they see in you

Time based version: set a twenty second window in which you actively scan for the earliest cue in a high stakes moment

Why it matters: Stress fingerprinting teaches your perception to move upstream in the stress arc. You are not waiting for the crash. You are catching the lift. This increases the window of intervention and reduces the period of hijack. Leaders who train early detection disrupt the default reflex of reacting first and thinking later. It prevents overcorrection and preserves high quality judgement in the moments that matter most.

The deeper truth: Stress rarely arrives in one piece. It arrives in fragments. When you learn to see the fragments you no longer get surprised by the wave. You do not need zero stress to lead well. You need awareness at the moment the wave begins. That awareness is the doorway to choice.

Micro recovery protocol

Stress tolerance is not simply about staying composed while pressure is present. It is equally about how quickly and cleanly you return to baseline after a high arousal moment. Most leaders do not lack skill in the stressful moment itself. What erodes wellbeing and clarity is the residue that remains afterwards. The nervous system holds on to activation long after the moment ends. If you do not clear it, the next conversation, the next meeting or the next decision is made on top of a nervous system that is already partially jammed.

Micro recovery is a short reset that follows a stressful spike. Two or three minutes is enough. The purpose is not reflection or analysis. It is physiological reset. You are signalling to the body that the threat has passed. You are telling your system that you are safe, the moment is complete, and it is time to return to neutral. This protects your capacity for what comes next.

Steps to take

1- Mark the end of the spike

Create a visible or physical cue that the acute moment is over. Close your notebook, push the chair back, stand up, or step to the doorway. Say to yourself, this moment has ended. If you are on a call, click end and pause before opening the next window.

Why: The body often stays in threat mode because there was no clear signal of completion. A brief ritual tells the nervous system to switch context from defence to recovery.

2 – Downshift breathing and pace

Take six to eight slow breaths with a longer exhale. If possible, walk slowly for twenty to thirty seconds or simply reduce your movement speed by a third. Keep shoulders loose and jaw relaxed.

Why: Long exhale and slower movement are the fastest bottom-up routes to reduce arousal. Pace and breath inform the autonomic system that urgency has passed.

3 – Discharge residual tension

Let the body release what it was holding. Shake out hands once, roll shoulders, circle wrists, unclench the jaw, stretch fingers, or stand and sway gently. Keep the movements small and unfussy.

Why: Muscles brace during stress. Small mobility work allows accumulated tension to leave rather than migrate into the next task as irritability or fatigue.

4 – Orient to the environment

Widen your attention to the space you are in. Look slowly around the room. Name three neutral objects silently. Feel the weight through your feet or the chair under you. Let eyes soften to widen peripheral vision.

Why: Orientation re-anchors perception in present space. The visual system strongly influences threat tone, so widening the field of view lowers background alarm.

5 – Re-enter with one intentional micro action

Choose the next tiny step on purpose. Send one email, sip water, review the next calendar line, or write one closing sentence about what just happened and stop. Then resume your day.

Why: Recovery is complete when behaviour restarts from choice rather than momentum. A small, deliberate move seals the reset and prevents rumination.

Examples

A finance director ends a difficult approval meeting where tension ran high. before returning to email she stands, walks to the window for thirty seconds, names three objects and breathes slowly until her shoulders drop. she returns to her desk clearer, not sharper.

An account manager leaves a call where the client pushed aggressively on price. he takes three slow breaths by the window, looks at the horizon and then deliberately walks slower back to his next conversation.

After a tough school run argument a parent pauses in the car before driving off. two minutes of grounding restores the body before the next part of the day begins.

After finishing a difficult phone call with a relative someone stands by the sink and slowly washes hands in warm water for thirty seconds. this signals to the body that the moment has ended.

Variations

Movement version: walk slowly for two to three minutes at a pace that is intentionally thirty per cent slower than your normal. The aim is not steps but decompression. Let the pace signal there is no chase.

Nature version: look at sky or tree canopy for one to two minutes. This widens peripheral vision, which reduces autonomic threat tone. The visual system is one of the fastest routes to calming.

Writing version: take a blank note or notes app and write one single sentence about what just happened and stop. The point is not processing. The point is closure. Short is more powerful than long.

Auditory version: listen to neutral sound for one minute such as rain, wind, fan noise or pink noise. not music. Music pushes emotion. Neutral sound resets baseline sensory load.

Micro touch version: wash hands in warm water for thirty seconds and feel the temperature consciously. Sensory grounding moves the brain from narrative to direct contact with experience.

why it matters: Micro recovery protects state hygiene. It prevents one charged moment leaking into the next. Most organisational reactivity is not caused by the moment itself but by residue from a previous moment, colouring perception. Small resets interrupt that contamination. They restore the signal-to-noise ratio in attention. The brain stops pattern-matching everything as a threat. Over a full day this produces a radically different cognitive landscape. Leaders become less brittle and more discerning. They do not need to try harder. They simply arrive clearer.

The deeper truth: Stress is only damaging when it does not finish. The body can metabolise intensity. What it cannot metabolise is unfinished activation that has nowhere to go. Micro recovery is an act of completion. It turns each stressful episode into a closed loop rather than a narrative that continues running in the background. Completion is a kindness to the future version of you. It preserves your capacity for the moments that have not yet arrived.

Brain dump reset

After stress spikes most leaders continue carrying the residue in their head. The moment might be over but the mind stays busy. There is a background loop that keeps the nervous system slightly activated. We try to hold tasks, questions, half-formed sentences and concerns inside working memory so they are not lost. This creates cognitive drag. The threat is not the stressor any more. The threat is the unparked fragments.

Brain dump reset is the practice of emptying the mind into an external container so the brain can release vigilance. The intention is not to solve or make meaning. It is simply to take what is rattling around internally and put it somewhere safe. When the fragments have a home outside the mind the nervous system can downshift. Working memory frees. Attention becomes available again for the next thing.

Steps to take

1 – capture the residue

Take a blank page, a note app or a clean document. List the raw fragments exactly as they appear in the mind. Use short phrases if that is your natural way of thinking. Or if the moment holds narrative tension then write one or two short sentences that describe the activation. Keep it fast and unedited. Let the pen or keyboard move faster than the judge in your head.

Why: the mind relaxes when it believes it is no longer the sole container. speed reduces over processing. accuracy of capture is not the point. transference is.

2 – Assign a return path

Decide where each item will live next. It could be tomorrow’s morning list, a specific calendar slot, a task system bucket, a whiteboard column, or a single checkpoint in your diary to revisit and decide later. You are not solving. You are locating a future touch point.

Why: stress often comes not from confusion but from lack of date. knowing when you will return to it is enough to release tension today.

3 – close the container

Close the note. Put the notebook away. Minimise the screen. Turn the phone over. Physically separate the capture from your visual field. This is the signal that the loop is now external and complete for now.

Why: the nervous system takes its cue from the body. a physical close is a more credible signal of completion than a mental intention.

Examples

After a tense commercial negotiation a project lead writes six short phrases in her notebook plus two sentences that hold the emotional tone. each line is then assigned to a place. once she closes the notebook she notices her chest relax.

After escalation from operations a CTO uses a notes app to brain dump three concerns and parks them on a calendar entry at 8.15 the next morning. he then returns to the product session present rather than distracted.

After a difficult call about a family member’s health someone writes one short sentence in the notes app and sets a reminder for tomorrow. this anchors the concern in a future slot and prevents carry over into the evening.

At the end of a draining day a teacher writes eight words on a bedside card and places it under the lamp. the body settles because tomorrow has been notified.

Variations

Free write variation: Set a two minute timer and write continuously without stopping. No structure. No editing. The aim is to discharge narrative pressure not to solve. When the timer ends close the page. Free writing gives the emotional system a fast exit route. It works well when the content holds strong feeling rather than tasks.

Voice capture variation: On the walk to the lift or car simply speak one or two sentences into voice notes. Do not over explain. One breath worth is enough. The power comes from speed and externalisation. This serves leaders who move between moments quickly and need hands free discharge.

Anchor task variation: Take one small actionable item from the dump and do it inside sixty seconds. Something tiny like send the meeting link or put one object into your bag. One small act is often enough to reassure the system that momentum exists. Small action seals completion.

Collect and return variation: Have one consistent page or note called parking lot. You return to that same place each time. The brain trusts the container because it is always the same home. This reduces the worry that fragments will disappear into different systems.

Why it matters: Unfinished thinking acts like low grade threat. It keeps the body alert because the mind cannot risk forgetting. Once the fragments are externalised and placed the alert system can relax. Leaders who brain dump reset arrive at the next moment with more cognitive bandwidth and more emotional steadiness. They are not carrying yesterday into today. They are present with what is in front of them.

The deeper truth: The mind was never meant to be storage. It was meant to be processing. When you remove the storage burden you return it to its rightful function. Brain dump reset gives you back to yourself. Presence is not a personality trait. It is a by product of reduced cognitive residue.

Five percent release

Stress does not always require a grand intervention to change direction. Most of the time the nervous system is not asking for a strategic reset. It is asking for a slight reduction in intensity so it can regain traction. The five percent release is a practice built around this principle. It teaches leaders to reduce pressure by tiny, workable increments in the moment rather than waiting for large windows of time that rarely arrive. It is the discipline of taking small agency while stress is still in motion rather than waiting for perfect conditions.

Most people delay recovery and tell themselves they will decompress once the meeting ends or once the quarter closes or once the inbox is under control. Yet stress does not accumulate in whole hours. It accumulates in micro residues across the day. The nervous system stores these residues whether or not the calendar allows a break. Five percent release is the antidote to that deferred recovery model. It is micro-recovery as a doing not micro-recovery as a promise. It builds the habit of adjusting the dial slightly and repeatedly so that you never fall so far into depletion that getting back becomes a separate project in itself.

steps to take

1 – feel where the stress has collected

Before doing anything, pause and take two slow breaths. Then scan the body with curiosity. Notice exactly where the residue is sitting. Shoulders pulled up. Jaw clenched. Upper chest tight. Hollow belly. Heat in the face. Do not interpret or judge the sensation. Just locate it, like marking a pin on a map.

Why: When you locate stress in the body, it stops being a vague psychological cloud. The nervous system shifts from abstract threat to specific sensation, which makes it changeable.

2 – ask one question

Silently ask yourself one line: what would reduce this by five per cent right now. Not solve. Not fix. Reduce by five per cent. The wording matters because it creates a small request that the nervous system can accept. Imagine you are adjusting a dial slightly, not swapping an entire machine.

Why: The nervous system resists big change when it is activated. Small achievable requests increase agency because they feel possible. Possibility downregulates fear.

3 – choose the smallest move that is still real

Look at the options available in this exact moment. Something that takes less than one minute. If you can send one short bridging message, do that. If you can get a drink of water, do that. If you can put one item in the correct folder, do that. If the tension is relational, park one single sentence into a notes page for tomorrow. Choose the option that requires no preparation.

Why: Behaviour is the fastest route to agency. The body learns agency through action, not insight. Small action interrupts paralysis.

4 – complete the action immediately

Do it inside the next sixty seconds. Do not think about whether another action would be better. The power is in immediacy. Even a tiny move pulls the nervous system forward and signals that this moment has changed. When you are done, take one short breath out and notice the drop.

Why: Immediate action stops rumination forming. Delay invites story. Movement tells the system that you are not stuck, which lowers threat tone quickly.

examples

Senior leader, work: After a tense pricing discussion, a commercial lead takes sixty seconds to write a single line summarising the next step and parks one clarifying question for tomorrow. The nervous system registers closure. The rest of the day is easier because there is no background swirl.

Project analyst, work: An analyst on a delayed tech delivery feels internal pressure building. She closes one browser tab and updates the top row of her kanban. It takes forty seconds. The pressure drops just enough for concentration to return.

Dentist’s waiting room: Someone waiting for an appointment feels anxious. Instead of spiralling, he stands up for one minute, walks to get a glass of water, and sits back down. Five per cent less activation, enough to stay present.

End of long commute: After a heavy commute home, a parent pauses in the car for sixty seconds before going inside. He takes three slow breaths and decides on one tiny gesture of generosity for the next quarter hour at home. Stress softens just enough that the arrival is human, not explosive.

variations

Micro-closure variation

Pick one loose end and close it. It could be as small as sending a quick follow-up email, ticking one checklist box, or deleting a redundant file. The act of closure restores a sense of completion, which signals the nervous system that the load is lighter.

Sensory reset variation

Change one sensory channel to signal a state shift. Step into natural light, rinse your hands under cool water, open a window, or stretch your arms wide. Physical contrast tells the body that the threat moment is over and it can recalibrate.

Social micro-repair variation

If tension involves another person, send a low-stakes bridge message: “Glad we resolved that,” or “Thanks for your time earlier.” This single act clears relational residue. The point is not reconciliation but emotional decompression through acknowledgement.

Cognitive park-and-return variation

When the mind keeps looping, take a scrap of paper or digital note and write one line: “Return to this tomorrow at 9am.” Then close it. By giving the worry a future slot, you teach the brain that the issue is contained and no longer needs constant attention.

why it matters

Stress compounds through residue, not through single spikes. Most leaders do not burn out because of one visible crisis but because they never clear the micro build-up between moments. Five percent release keeps the system mobile and responsive. By learning to reduce stress in small increments, you maintain capacity across the day. Tiny releases prevent exhaustion from becoming identity. They keep flexibility alive.

This practice also builds psychological confidence. Each micro-action is a vote for your own capability. Over time, these small acts recondition your brain’s sense of control. When pressure arrives, your system already knows how to shift state rather than freeze.

the deeper truth

Recovery is not an event. It is a rhythm. Five percent release teaches the nervous system that you do not need to win the whole moment to regain control. You only need to move it slightly. Most resilience is not heroic; it is incremental. The real art of composure lies in reclaiming choice in fragments, not in grand resets. Over time, these small shifts accumulate into durable steadiness. The body learns that control is not something you achieve later. It is something you practise now.

Conclusion: the art of staying steady inside activation

Stress tolerance is not the absence of stress. It is the capacity to stay grounded while stress is present. It is the skill of maintaining clarity, agency, and perspective in the moments when the nervous system is activated. This is what allows leaders to remain composed under scrutiny, to stay relational when challenged, and to think clearly when urgency presses for speed rather than wisdom.

The practices in this section are designed to strengthen that capacity. They do not aim to eliminate pressure but to change your relationship with it. Some practices address stress before it arrives by building preparedness and reducing shock. Others support presence in the heat of the moment so that activation does not hijack behaviour. And some restore balance afterwards so that strain does not accumulate across the day. Together they form a training ground for the nervous system rather than a rescue kit for collapse.

This matters because unmanaged stress is not simply uncomfortable. It is costly. Under pressure, perceptual bandwidth narrows, conflict escalates faster, and judgement deteriorates. Wellbeing erodes not in obvious breakdowns but in a slow drift into fatigue, impatience, and emotional rigidity. Leaders who cannot regulate stress become brittle and reactive. They perform their job while gradually losing access to their best thinking.

Stress tolerance protects the capacity to choose. It preserves the ability to respond rather than react. Leaders who build this discipline remain connected to purpose, values and perspective while the body is activated. They can hold discomfort without needing to escape it. They can uphold standards without turning to control. And they can navigate turbulent conditions without being consumed by them.

Ultimately, stress tolerance is a foundational leadership capability because leadership is not performed in ideal conditions. It is performed in constraint, pressure, trade-off and uncertainty. Stress tolerance turns these conditions into workable ground. It asks a grounding question that keeps leadership human: In this moment of activation, what action would reflect who I want to be?

Reflective questions

- Where does pressure most reliably hijack your behaviour or tone?

- Which stress signals are early enough that you could intervene sooner?

- What are your most reliable micro habits when you recover well?

- Which practice in this chapter could you use today, not later, while pressure is still present?

- If you aimed to reduce stress by five per cent rather than fifty, what would change?

Stress tolerance is not a finish line. It is a living discipline. With practice, you reclaim agency from urgency and replace strain with steadiness. Over time, activation becomes information rather than threat. That shift is the beginning of resilient leadership.

Do you have any tips or advice on stress tolerance?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

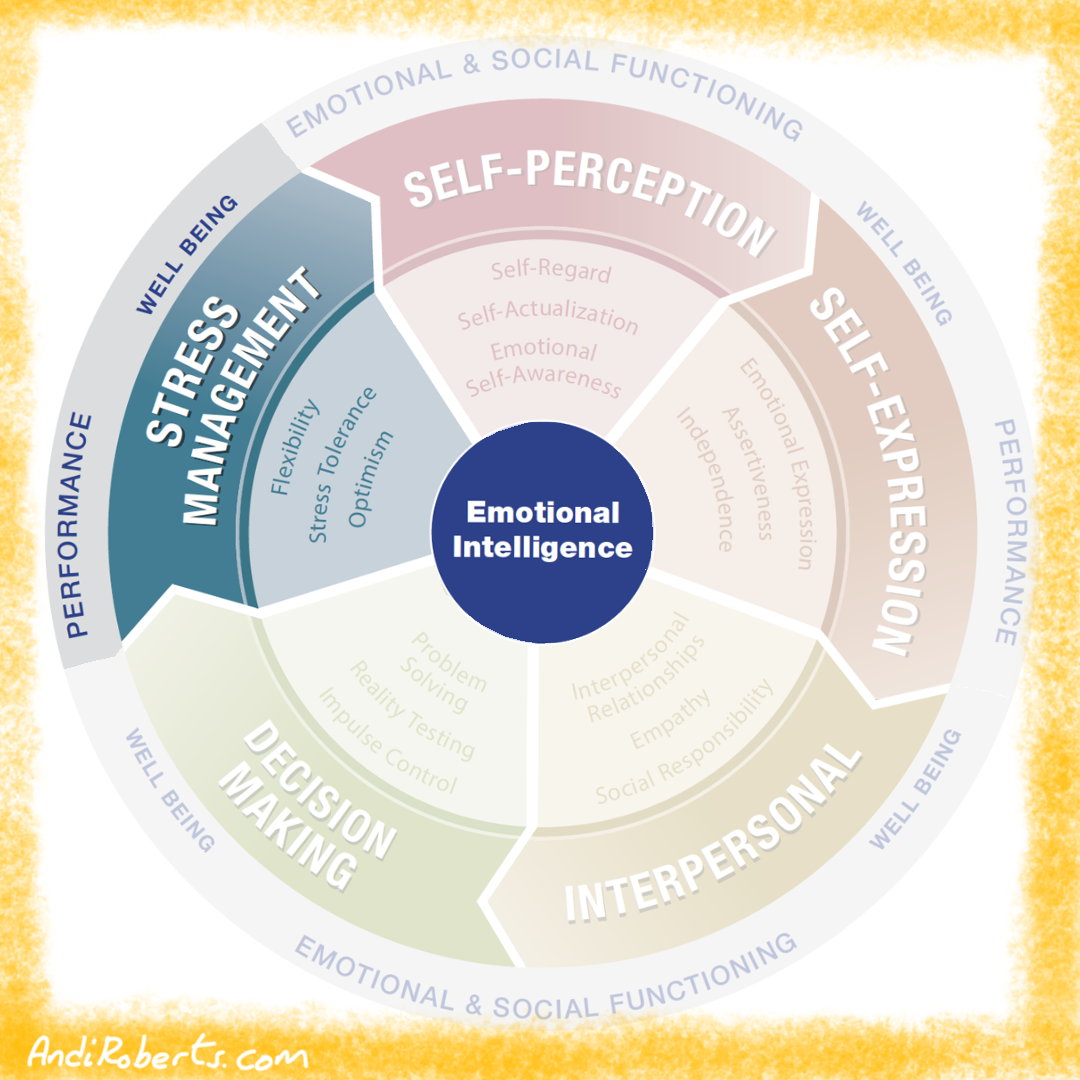

Stress tolerance is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Optimism and Flexibility in the Stress Management facet.

Sources:

Bonanno, G.A. (2004) ‘Loss, trauma, and human resilience’, American Psychologist, 59(1), pp. 20–28.

Gross, J.J. (2002) ‘Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences’, Psychophysiology, 39(3), pp. 281–291.

McEwen, B.S. (2007) ‘Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation’, Physiological Reviews, 87(3), pp. 873–904.

Sapolsky, R.M. (2004) Why zebras do not get ulcers. 3rd edn. New York: Holt.

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E. (2011) The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. 3rd edn. Mississauga: Jossey-Bass.

Leave A Comment