This guide explains emotional flexibility and offers practical exercises to help leaders stay calm under pressure, adapt to change and remain open when plans evolve.

Modern leadership takes place in conditions of constant movement. Strategies shift, markets evolve, and teams face continuous disruption. In this environment, rigidity becomes a liability. Flexibility is not about being indecisive or inconsistent. It is the capacity to adjust thinking, behaviour, and emotion in response to new information or changing demands, without losing core purpose or stability.

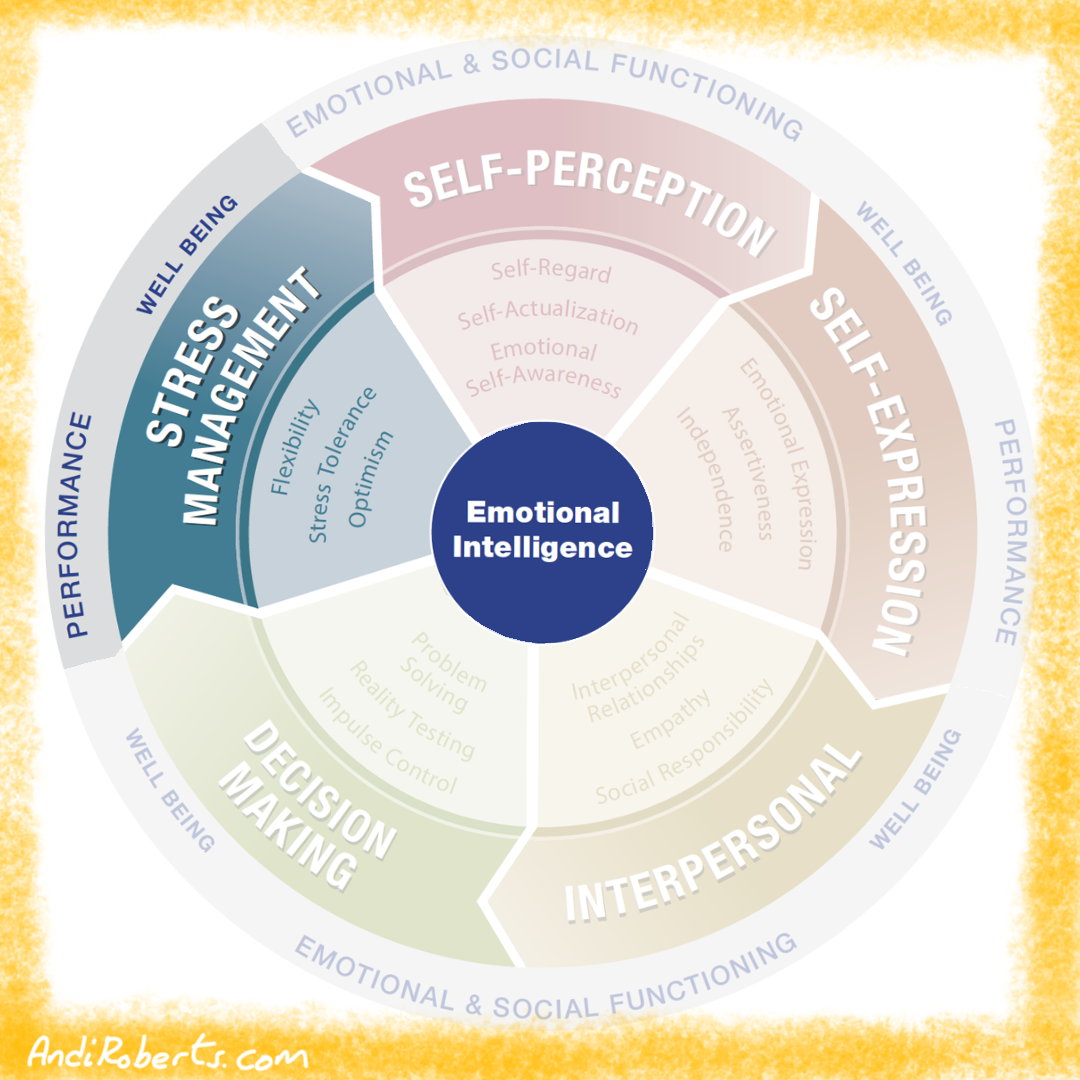

In the EQ-i model, flexibility is defined as the ability to adjust one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviours to unfamiliar, unpredictable, and dynamic circumstances (Stein & Book, 2011). It is what allows a person to move fluidly between perspectives, to release a plan that no longer fits, and to find composure in uncertainty. Flexible leaders are not simply tolerant of change; they work with it consciously, using curiosity and openness to turn disruption into insight.

Without flexibility, even capable leaders become trapped by habit. They cling to past methods, resist new ideas, or struggle when situations deviate from the expected. This resistance often arises not from stubbornness but from fear of losing control or competence. Over time, inflexibility narrows perception, slows decision-making, and diminishes creativity. When change inevitably arrives, it feels threatening rather than energising.

With flexibility, leaders adapt without abandoning their principles. They shift between analysis and intuition, between planning and improvisation, between confidence and humility. They can respond to evolving circumstances with both stability and openness. Research on adaptability and cognitive flexibility shows that those who reframe change as information rather than danger experience lower stress and perform more effectively in complex environments (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Martin & Rubin, 1995).

Flexibility also acts as a bridge between emotional and cognitive intelligence. It balances persistence with learning, conviction with curiosity, and direction with discovery. It enables empathy by allowing a person to consider perspectives that differ from their own. It strengthens problem-solving by widening the range of possible approaches. It even supports impulse control and reality testing by helping leaders release unhelpful reactions and see multiple sides of a situation.

Why flexibility matters

If flexibility is the capacity to adapt to what is changing while staying centred in what matters, why is it such a vital leadership skill? The answer lies in its ability to sustain both effectiveness and wellbeing.

Resilience under change: In periods of rapid transformation, leaders face ambiguity that challenges their assumptions. Flexibility allows them to absorb disruption without becoming destabilised. By staying open to what is emerging, they recover faster and maintain direction when others lose clarity.

Better decision-making: Flexible leaders are able to reframe problems and consider new options. They recognise when conditions have changed and when a different approach is needed. Research on cognitive adaptability shows that this openness leads to more creative solutions and better long-term outcomes (Kahneman, 2011; Dweck, 2006).

Stronger collaboration and trust: Teams thrive under leaders who are consistent in values but adaptive in methods. Flexibility signals respect for others’ ideas and responsiveness to reality. It helps prevent conflict born from rigidity and encourages dialogue grounded in mutual understanding.

Within the EQ-i framework, flexibility supports multiple emotional competencies. It enables stress tolerance by allowing adjustment under pressure. It enhances problem-solving by expanding mental models. It strengthens interpersonal relationships by fostering empathy and perspective-taking. Flexibility is not a loss of structure; it is the intelligent use of structure in motion.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Flexibility refers to the ability to adjust emotions, thinking, and behaviour in response to unfamiliar, unpredictable, and changing circumstances. High scores are not automatically better. When flexibility is underused, leaders can become rigid, closed, and stuck in habitual patterns even when the environment has already shifted. When overused, they can become inconsistent, easily influenced by others, and too quick to abandon an idea or direction. The continuum below illustrates how this composite typically looks at different levels of expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Rigid and resistant to new ideas |

Adapts approach without losing direction |

Too changeable and inconsistent |

|

Sticks to familiar patterns even when ineffective |

Open to alternative methods or viewpoints |

Easily swayed by others |

|

Difficulty shifting perspective |

Able to revise assumptions in real time |

Lacks commitment or follow through |

|

Gets stuck in habitual responses |

Behaviour changes are intentional and proportionate |

Abandons ideas too quickly |

|

Needs certainty before acting |

Uses flexibility as a strategic capability |

“Change junkie” behaviour, novelty seeking |

Balancing factors that keep flexibility adaptive not chaotic

Flexibility is most effective when it is supported by complementary EQ i skills that ensure adaptation remains purposeful rather than reactive. These balancing scales help leaders distinguish healthy flex from random shape shifting.

Problem Solving: Problem solving provides analytical structure. Change only has value if it improves the reasoning quality. Without this scale, flexibility becomes novelty. With it, flexibility becomes strategic choice. It keeps adaptation rooted in evidence rather than emotional avoidance.

Independence: Independence prevents flexibility from collapsing into people pleasing. Leaders who stay centred in their own judgement can shift without losing their point of view. Independence ensures that adaptation remains self authored rather than driven by external validation.

Impulse Control: Impulse control slows the reflex to pivot. It ensures flexibility is considered rather than automatic. Leaders can still change direction, but they do so with intention rather than emotional reactivity. This scale converts flexibility from reaction into option selection.

Eight practices for strengthening flexibility

Flexibility grows through deliberate experimentation, reflection, and reframing. Each practice in this section explores a different aspect of adaptability: interrupting old patterns, shifting perspectives, stretching scenarios, and restoring balance after emotional disruption.

Each practice follows the same structure:

Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

Steps to take guide you through the process.

Examples show it in real contexts.

Variations suggest ways to adapt.

Why it matters grounds the practice in research and insight.

Flexibility, at its core, is the art of staying responsive without losing integrity. It allows leaders to navigate complexity with confidence, turning uncertainty into learning and disruption into renewal.

Pattern interrupt

Much of what undermines flexibility happens before we notice it. We fall into grooves of thought, language, and reaction that once served us well but now limit our options. The same meeting routines, the same defences when challenged, the same quick judgements about people or plans. These patterns are efficient, but they are rarely intelligent. Flexibility begins when we interrupt them.

Pattern interrupts are deliberate acts of awareness. They create a pause long enough for a different response to emerge. Research in cognitive psychology shows that most behaviour is guided by automatic scripts rather than conscious reasoning (Kahneman, 2011). Under pressure, these scripts tighten: we default to familiar responses even when the context has changed. A conscious break in that sequence restores agency. It moves the mind from reacting to responding.

Steps to take

1 – Spot your loops

Identify one or two recurring situations where your reactions feel predictable. It could be how you respond to criticism, how you start meetings, or how you manage conflict.

Why: Awareness is the entry point for flexibility. When you name a pattern, you create distance from it. You begin to see behaviour as something you do, not something you are.

2 – Label the trigger

When the moment arises, silently name what is happening: “Here comes my control reflex” or “I’m rushing to fill silence again.”

Why: Labelling a trigger recruits the brain’s language and reasoning centres. This reduces emotional reactivity and increases the likelihood of making a conscious choice rather than a habitual one.

3 – Do something different

Change one element of your normal pattern. If you always speak first, pause and let others contribute. If you withdraw, ask one curious question.

Why: Doing something different teaches the nervous system that safety and identity do not depend on old routines. Even small acts of deviation expand behavioural range and make adaptability more natural.

4 – Reflect soon after

Within a few hours, note what happened and how it felt. Did the outcome shift? Did tension ease? Did new perspectives appear?

Why: Reflection transforms the experiment into learning. It strengthens awareness and reveals how the new behaviour changed the dynamic, building confidence to repeat it.

5 – Reinforce the new route

Each time a new response works better, acknowledge it. This helps consolidate the neural pathway so the more adaptive pattern becomes easier next time.

Why: The brain learns through repetition and reward. Recognising success turns flexibility from an effortful practice into an automatic strength.

Examples

Project team: A project manager realises that she interrupts whenever discussions drift. She starts counting to three before responding. In doing so, she notices that colleagues often resolve points on their own. The pause reduces tension and increases trust.

Design review: An engineer sees his habit of dismissing ideas quickly. He decides that once a week he will deliberately explore a suggestion he would normally reject. The result is not only better designs but also stronger collaboration.

Family reset: A parent notices that every family argument follows the same pattern: raised voices, retreat, silence. They introduce a “reset word” that anyone can use to signal a restart. The next disagreement ends with laughter instead of slammed doors.

Personal wellbeing: A runner recognises that stress drives her to overtrain. She replaces her usual reaction with a five-minute breathing routine before deciding whether to run. Most days, she still trains but now from choice, not compulsion.

Variations

Team version: Invite team members to identify one collective pattern the group could interrupt, such as over-analysis or constant urgency.

Fast version: Use a physical cue like unclenching your hands or standing up to reset attention.

Reflective version: Journal one recurring pattern per week and describe what a different response might look like.

Coach-assisted version: Ask a peer or mentor to observe your language and highlight repeated scripts.

Organisational version: Apply during project reviews to identify systemic loops, such as recurring delays or decision bottlenecks, and test alternative behaviours.

Why it matters: Interrupting patterns builds flexibility because it weakens the automatic links between trigger and reaction. Neurologically, it strengthens the prefrontal cortex’s capacity to override habitual responses, enhancing emotional and cognitive control (Ochsner and Gross, 2005). Psychologically, it nurtures tolerance for ambiguity, a key attribute in leaders who navigate complexity.

In organisations, flexibility separates those who adapt from those who entrench. Teams that challenge their collective habits learn faster, avoid repetitive errors, and stay innovative under constraint. Pattern interrupts restore agency in systems where routine has replaced reflection. They remind people that choice is always available, even when conditions feel fixed.

The deeper truth: Flexibility is not about endless change but about conscious movement. It means being able to shift course without losing integrity. Every time you interrupt an old pattern, you reclaim a small piece of freedom from habit and ego.

Over time, these small interruptions accumulate into transformation. You become less bound by reaction and more guided by intention. In that space between the old reflex and the new response lies the essence of adaptability: the ability to stay true to your purpose while meeting the world as it really is.

Perspective shifting

Flexible leaders know that their first interpretation is rarely the only one. When faced with disagreement or confusion, their instinct is not to defend their view but to explore another’s. Perspective shifting is the practice of deliberately seeing a situation through someone else’s frame of reference. It does not mean agreeing, but it does mean understanding deeply enough to describe their view as they would.

In the EQ-i framework, flexibility involves openness to new information and willingness to adjust. Perspective shifting is one of its most practical forms. It stretches empathy, improves decision quality, and reduces conflict born of assumption. It helps you lead with awareness rather than certainty.

Steps to take

1. Choose a situation of tension

Select a real situation where you feel misunderstood, frustrated, or certain you are right. It might be with a colleague, client, or family member. Choose something emotionally safe enough for reflection but real enough to matter.

Why: Perspective shifting has little value in theory. Working with live tension grounds the practice in emotion, where rigidity usually appears first. Real stakes make insight stick.

2. Describe your view first

Write a short paragraph about the issue from your perspective. Note what you think happened, what you value, and what you believe should occur next. Be honest about your reasoning and feelings.

Why: Capturing your own stance first clarifies the lens through which you are seeing. It externalises bias and assumption, giving you a clearer baseline before stepping into another view.

3. Step into their frame

Now write a second paragraph as if you were the other person, using “I” language. Describe the same situation as they might see it: their goals, concerns, pressures, and interpretations. Use empathy and imagination rather than judgement.

Why: This is the essence of perspective shifting. By writing from their point of view, you override the mental shortcut that assumes others think as you do. It activates curiosity and slows reactive certainty.

4. Identify what matters most to each side

Under each paragraph, list the underlying needs, fears, or values driving the behaviour. For you, it might be control, clarity, or fairness; for them, it might be autonomy, recognition, or speed.

Why: Understanding motives transforms conflict. When you see what is at stake beneath behaviour, your options for collaboration multiply. It becomes easier to respond constructively rather than defensively.

5. Find the overlap and the blind spot

Circle what both sides value and highlight what only one side is protecting. The overlap is your bridge; the blind spot is your growth edge.

Why: This analysis reveals how difference can complement rather than compete. Shared values remind you that disagreement often arises not from opposition but from prioritisation. Recognising this reduces emotional charge.

6. Adjust one behaviour

Decide on one practical behaviour you can change based on what you have learned. It might be asking more questions before responding, offering reassurance, or changing the way you present an idea.

Why: Perspective shifting becomes meaningful only when it shapes action. A small behavioural change signals genuine understanding and invites reciprocity. Over time, this builds trust and emotional agility.

Examples

Project collaboration: A designer feels frustrated that a project manager keeps asking for detailed plans. Writing from the manager’s view reveals a fear of last-minute surprises. The designer starts sending early updates, easing tension and improving cooperation.

Feedback conversation: A leader feels attacked by a team member’s criticism. Stepping into the other’s frame shows that the team member was seeking recognition, not confrontation. The leader responds with appreciation, turning conflict into openness.

Customer relationship: A consultant believes a client is indecisive. Writing as the client shows that they are balancing internal politics. The consultant slows the pace, builds clarity, and wins longer-term trust.

Family dynamic: A parent assumes a teenager is lazy about chores. Writing as the teenager reveals a wish for autonomy. Negotiating shared ownership transforms friction into dialogue.

Variations

-

Two-chair reflection: Physically switch seats to speak from each perspective aloud.

-

Email empathy: Before replying to a difficult message, rewrite it from the sender’s imagined point of view.

-

Values mapping: Use sticky notes to list what each party values most and where overlap exists.

-

Emotional mirror: Note the emotion you feel and ask, “What might they be feeling that mirrors this?”

-

Daily pause: Practise shifting perspective once each day, even in minor situations such as traffic or meetings.

-

Third-party lens: Imagine how an impartial observer might describe the dynamic between you both.

Why it matters: Perspective shifting builds flexibility by loosening the grip of certainty. It expands the emotional and cognitive space in which you operate. Leaders who practise this consistently are more resilient because they interpret challenges with greater nuance. They do not collapse complexity into blame.

Research on conflict and decision-making shows that perspective-taking reduces defensiveness, increases cooperation, and improves creative problem-solving (Galinsky et al., 2008). In fast-changing environments, this capacity to see through multiple lenses becomes a decisive advantage.

The deeper truth: The most rigid moments in leadership are rarely about facts. They are about identity: the need to be right, seen, or respected. Perspective shifting softens that grip. It reminds you that understanding another view does not diminish your own; it expands it.

When you practise this often, you start noticing how every opinion is a partial truth. Each perspective contributes to a larger picture that no one person can see alone. Flexibility, then, is not weakness. It is a sign of maturity—the ability to stand in uncertainty without losing yourself.

True openness is not agreement. It is the discipline of curiosity, even when emotion rises. In that space, empathy becomes intelligence in action.

Cognitive reappraisal

Flexibility is not only mental but emotional. The ability to reinterpret events, to see meaning differently, allows you to steer emotional responses instead of being ruled by them. This is the skill of cognitive reappraisal: consciously reframing a situation to alter its emotional impact without denying reality.

Research shows that reappraisal is among the most effective and sustainable forms of emotion regulation (Gross and John, 2003). It helps people experience fewer negative emotions, recover more quickly from stress, and maintain better relationships. Unlike suppression, which hides emotion but increases tension, reappraisal transforms how we understand events, changing feeling through meaning.

Steps to take

Notice the trigger in real time

Catch yourself in the moment when emotion surges such as frustration, disappointment, defensiveness, or fear. Pause long enough to name what you are feeling and what triggered it. The aim is not to suppress, but to recognise the spark before it becomes a flame.

Why: Awareness is the first doorway to flexibility. You cannot change what you cannot see. Recognising emotion as it arises activates your prefrontal cortex, making reflection possible and keeping the reaction from taking full control.

Label the interpretation, not just the emotion

Beneath every feeling lies a thought or judgement: “They disrespected me,” “I failed,” or “This is unfair.” Write or silently name that interpretation. Do not correct it yet; simply make it visible.

Why: Emotions are fuelled by interpretation. By naming the thought that gives rise to emotion, you move from being inside the reaction to observing it. This separation allows you to choose whether the thought is accurate or helpful.

Generate alternative explanations

Deliberately create two or three other ways of viewing the event. For instance: “They might be under pressure,” “I may have misread the tone,” or “This is feedback, not rejection.” Even if they feel artificial at first, explore them as possibilities rather than replacements.

Why: Reappraisal is not positive thinking; it is plural thinking. By widening the interpretive field, you loosen the hold of any single story. The emotional intensity drops because certainty softens.

Test the emotional shift

Revisit the situation through each new lens and notice how your emotional state changes. What happens to your body, your breathing, or your sense of proportion? Which interpretation allows you to stay most resourceful and fair?

Why: Feelings are feedback. Observing emotional change helps you sense which interpretation supports wise action. This testing phase strengthens the link between cognition and physiology, which is the essence of self-regulation.

Act from the grounded frame

Choose the interpretation that balances realism and calm. Use it to guide your next action, such as a question you ask, a tone you adjust, or a boundary you set. Afterwards, note how this change of meaning influenced the outcome.

Why: Emotional intelligence exists to improve real-world effectiveness. Acting from the reappraised frame completes the loop: insight becomes behaviour. Each time you do this, you reinforce a neural pattern of pause, reinterpret, and respond.

Examples

Customer interaction: A service lead feels slighted by a client’s abrupt email. Instead of replying defensively, she pauses and reappraises: “He is probably under intense time pressure.” The empathy calms her tone, and the conversation resolves quickly.

Team meeting: During a heated discussion, an engineer interprets a colleague’s interruption as dismissal. Catching the thought, he reframes it: “She is passionate, not disrespectful.” The meeting continues with less friction and more focus.

Leadership feedback: A director receives a blunt performance review and initially thinks, “They do not value me.” Later, he reframes it as “They believe I can do better.” The new frame turns resentment into motivation.

Personal setback: After losing a major pitch, a consultant reinterprets it as useful data: “We learned where our assumptions broke down.” This mental shift restores perspective and energy for the next opportunity.

Variations

-

Real-time reappraisal: Practise during live interactions. Notice tone, pace, or phrasing that trigger emotion and immediately search for alternate meanings.

-

Post-event reflection: After a stressful day, journal one event that evoked emotion. Write the initial thought, two reappraisals, and what each changes in feeling.

-

External perspective: Ask a trusted colleague, “How else might you read what happened?” Borrowing another’s interpretation trains mental agility.

-

Somatic anchor: Pair reappraisal with breathing or posture changes. When the story softens, let the body follow.

-

Language reframing: Replace absolute words such as “always,” “never,” or “disaster” with balanced ones such as “often,” “sometimes,” or “challenge.” Language precision shapes emotion.

-

Future lens: Imagine explaining the event to yourself six months later. What story would you tell then?

-

Coaching dialogue: Use reappraisal as a live coaching tool: “What might be another way of understanding this?”

-

Values lens: Reframe the event in terms of a core value: “How could courage or integrity guide my interpretation here?”

Why it matters: Cognitive reappraisal is both a stress management tool and a leadership discipline. Research consistently shows it predicts higher wellbeing, better interpersonal functioning, and lower emotional exhaustion (Gross and John, 2003; Troy et al., 2010). People who reappraise effectively experience emotion as informative rather than overwhelming.

In teams, this skill transforms culture. Leaders who can reinterpret feedback, setbacks, and conflict in constructive terms model emotional steadiness. They reduce contagion of negativity and encourage others to face tension with curiosity instead of fear. Over time, reappraisal creates climates of trust and psychological safety, the soil of adaptability.

The deeper truth: Every emotion carries a story. Cognitive reappraisal teaches that while the feeling is real, the story is optional. This realisation expands both freedom and responsibility. You cannot always control what happens, but you can control the frame through which you make meaning.

In a volatile world, leaders often face moments when control is lost and perception is all that remains. Reappraisal turns those moments into mastery. It is not denial or detachment, but disciplined interpretation, the art of turning reaction into reflection, and reflection into wiser response.

The deeper truth is that flexibility begins with compassion: for your own mind, which leaps to protect you, and for others, whose actions often make sense in ways you cannot yet see. Reappraisal invites you to pause between event and emotion, the space where choice lives. And in that space, every leader finds not control over life, but freedom within it.

Value core, flex surface

Flexibility is not the same as inconsistency. True adaptability comes from knowing what must stay firm and what can bend. Leaders who flex too easily risk losing credibility, while those who never flex become rigid and disconnected from changing realities. The art lies in holding steady at the core while allowing movement at the surface.

Values provide that core. They define who you are and what principles guide your choices, even when context shifts. Around that core sits behaviour, which can change with situation, audience, or time. This exercise helps you clarify which parts of yourself are non-negotiable and which are available for adaptation. The aim is to develop a stable inner compass that allows outer agility.

Steps to take

1. Clarify your value anchors

List five personal values that matter most to you in how you lead. These might include fairness, learning, courage, humility, or care. Then narrow the list to three that feel essential, values without which your sense of integrity would weaken.

Why: Clarity about core values reduces overreaction under pressure. When values are named, leaders can adjust actions while staying true to purpose. Research shows that value affirmation increases stress tolerance and decision consistency (Sherman and Cohen, 2006).

Case example: Maria, a regional operations director, is leading a project that has fallen behind schedule. Under pressure from the executive team, she feels torn between two impulses: to push harder on her team or to listen and support them. She lists her five top leadership values and identifies three that matter most: fairness, transparency, and care. Seeing them written down reminds her that fairness is not optional; it is who she is as a leader. That clarity helps her breathe more steadily amid the noise of deadlines.

2. Identify flexible zones

For each of your three core values, write down what that value looks like in behaviour. Think of the ways you usually express it. For example, if your value is fairness, you might normally demonstrate it by asking for everyone’s input before making a decision. If your value is respect, you might show it through direct feedback and honest conversation.

Next, consider alternative expressions that would still honour the value but fit different situations. Fairness could also mean making a quick decision when delay would disadvantage the team. Respect might mean pausing feedback until emotions have settled. The question to keep asking is, “What is the essence of this value, and what forms can it take?”

Write at least two contrasting expressions for each value. This helps you separate the value itself (the principle you will not compromise) from the behaviour (the method that can vary).

Why: Many people mistake their preferred style for a moral position. They equate being fair with consulting everyone, or being honest with being blunt. This limits flexibility and creates unnecessary conflict. By identifying flexible zones, you learn to adapt without abandoning your integrity. Leaders who master this distinction adjust behaviour confidently because they know what is constant beneath the surface.

Case example: Under normal circumstances, Maria lives fairness by gathering every team member’s input before acting. But the project delay makes that approach impractical. She sketches two behavioural versions of fairness:

-

Version A: Full consultation before decisions.

-

Version B: Transparent explanation after a quicker decision.

-

She realises both honour fairness, just in different forms. By choosing Version B, she still acts from fairness, explaining her reasoning and showing consistency, but without slowing progress.

3. Map tensions between core and surface

Think of recent situations where your values and context seemed to clash. For example, valuing openness in a culture that rewards restraint, or valuing directness in a setting that prizes diplomacy. Note how you managed those tensions. Did you hold the value but shift the behaviour, or did you sacrifice the value to fit in?

Why: Seeing these moments clearly turns abstract values into lived practice. The reflection builds awareness of when you are anchored and when you drift.

Maria’s moment: In the following week, a senior executive challenges Maria publicly for missing a milestone. Her instinct is to defend herself, but her value of transparency reminds her to stay open. Instead of reacting, she acknowledges the issue, outlines the plan, and later gives her team a calm update. Later reflection shows her that she kept the core value intact (transparency) but flexed the surface behaviour (tone and timing). She did not hide, but she also did not escalate.

4. Draft your guiding sentence

Write one sentence that captures how you want to combine firmness and flexibility, such as: “I will stay rooted in honesty while choosing the form that serves the situation.” Keep it visible for a week and revisit after key conversations or decisions.

Why: A concise personal statement transforms reflection into guidance. It serves as a quick reset under pressure and helps maintain alignment between identity and action.

Maria’s moment: At the end of the month, Maria writes her sentence: “I will stay rooted in fairness and transparency while adapting the form that keeps people moving.” She prints it on a small card and keeps it by her laptop. When deadlines tighten, she glances at it as a visual reminder that firmness and flexibility can coexist.

Examples

Project pressure: A leader under performance stress clarifies her top values and recognises that fairness can take multiple forms. She shortens decision cycles while explaining her reasoning, keeping the principle intact but adapting the process.

Cross-functional tension: A programme manager values collaboration but learns that some partners prefer autonomy. She reduces meeting frequency but maintains shared clarity through transparent updates, preserving collaboration without excess coordination.

Family balance: A parent values responsibility but learns that sharing it means allowing others to take different paths to the same goal. They remain anchored in the value but flex on method.

Mentorship: A coach values honesty but tempers blunt feedback with curiosity, ensuring the message is heard rather than resisted.

Variations

-

Value cards: Write your top five values on cards. In moments of tension, shuffle and pick the one most relevant to the situation. Ask, “What would this value look like here?”

-

Contrast diary: Keep a short log of when you stood firm and when you flexed. Review patterns over a month to identify balance or drift.

-

Colleague mirror: Ask trusted peers what values they see you hold most consistently and where they notice flexibility.

-

Boundary experiment: Choose one situation this week to flex more deliberately and one to hold more firmly. Reflect on impact.

-

Mentor dialogue: Discuss with a mentor when flexibility risks becoming compromise. Learn from their experience of balance.

-

Morning cue: Before starting the day, remind yourself of one value and one behaviour you may need to flex.

Why it matters: Anchoring flexibility in values prevents adaptability from sliding into inconsistency. Research on authentic leadership shows that when behaviour aligns with core values, trust and engagement increase even during change (Avolio and Gardner, 2005). Conversely, when leaders shift behaviour without a visible moral anchor, teams perceive instability and withdraw confidence.

Values act as cognitive stabilisers. They simplify complex environments by offering consistent decision criteria. At the same time, flexibility at the behavioural level keeps those values effective in diverse contexts. Leaders who practise this balance adapt faster because they are not defending ego or habit, only principle. They remain both steady and responsive.

The deeper truth: Flexibility without grounding drifts into pleasing or avoidance. Grounding without flexibility hardens into control. Leadership maturity lies in navigating between these poles. When you know what defines you, you can enter new situations without losing yourself.

Anchored flexibility is the quiet confidence that says, “I can change how I act without changing who I am.” It is the quality that allows leaders to move between cultures, teams, and crises with integrity intact. Over time, this balance builds the reputation that matters most: not of being unshakable, but of being steady enough to bend.

Change rehearsal

Adaptability is not only tested in moments of change; it is strengthened through practice. Just as athletes visualise their moves before the game, flexible leaders mentally and emotionally rehearse change before it arrives. By pre-playing possible futures, they reduce reactivity and increase the speed of recovery when circumstances shift.

The aim of this exercise is to make flexibility a habit rather than a reaction. You do this by imagining and practising adjustments in advance, using both reflection and small behavioural trials. In doing so, you build a wider repertoire of responses that keeps you steady when the unexpected occurs.

Steps to take

1. Identify an upcoming or potential change

Think of a situation where you anticipate change: a new strategy, role transition, technology shift, or team restructure. Choose one that carries a mix of uncertainty and personal stakes.

Why: Starting with a tangible context grounds the rehearsal in reality. Abstract change rarely provokes genuine reflection or emotion. Working with a real scenario brings the emotional material to the surface and prepares you for what flexibility will actually demand.

2. Map your likely reactions

Describe how you would typically respond if the change occurred today. Note emotional, cognitive, and behavioural reactions. For instance, would you resist, seek more information, withdraw, or jump into problem-solving? Write these responses down without editing.

Why: Self-awareness precedes self-management. Mapping your default responses makes automatic patterns visible. Once seen, they can be shaped rather than repeated.

3. Rehearse alternative responses

Now imagine the same scenario, but this time choose a response that expresses openness and learning. Ask: “What would a flexible version of me do?” Picture yourself acting that way in detail, including tone, posture, words, and timing. The goal is to create a clear mental script.

Why: Neuroscience shows that mental rehearsal activates similar neural pathways as actual behaviour (Jeannerod, 1994). Practising flexibility in imagination strengthens readiness and reduces threat perception when change occurs.

4. Trial a micro-behaviour

Select a small, safe situation this week where you can test one aspect of flexibility: trying a new tool, asking for feedback, or letting someone else lead a discussion. The point is to make flexibility observable, not just imagined.

Why: Flexibility develops through repeated low-risk experiments that gradually expand tolerance for uncertainty. Small actions build confidence and make adaptability a default habit rather than an exception.

5. Reflect and refine

After the real or imagined practice, take five minutes to capture what felt easy, what felt hard, and what surprised you. Ask yourself, “What did I learn about my flexibility?” Identify one insight to carry forward.

Why: Reflection turns experience into learning. Without it, rehearsal becomes repetition. Reviewing the outcome anchors insight and increases intentionality next time.

Examples

Leadership transition: A manager preparing to take over a new team rehearses first-week conversations, imagining scenarios where people resist direction. By visualising calm, curious responses, she starts the role with composure.

Technology shift: An analyst anxious about AI automation practises responding to new tools with curiosity rather than comparison. When the rollout comes, he engages early, becoming a local champion instead of a sceptic.

Family relocation: Before moving abroad, a couple visualises the first month’s stress points and their coping strategies. This rehearsal helps them handle disorientation with humour and empathy.

Public speaking: A leader who fears questions from senior stakeholders rehearses answering with pauses and clarity. When asked on the day, she feels less startled and more grounded.

Variations

-

Mental movie: Close your eyes and imagine a future scenario of change from start to finish. Visualise your body language, tone, and calmness.

-

Role play: Ask a trusted colleague to play the part of a difficult stakeholder. Practise staying steady while exploring solutions.

-

Reverse rehearsal: Instead of imagining success, rehearse the moment of failure and how you recover. This strengthens resilience rather than perfectionism.

-

Flexibility cue: Choose a short phrase like “reset” or “breathe” to remind yourself during real change moments to act from choice, not reflex.

-

Pre-commitment: Write one small adaptive action you will take next week and share it with a colleague for accountability.

-

Weekly reflection: Every Friday, note one situation that required flexibility and how you responded. Observe patterns of growth.

Why it matters: Change rehearsal builds psychological readiness. When people mentally and behaviourally prepare for disruption, their brains register novelty as challenge rather than threat. This reduces cortisol levels and increases creative problem-solving under pressure (Jamieson et al., 2013).

It also normalises discomfort. Leaders who practise small flexibility acts develop a wider emotional range and lower reactivity. They no longer treat change as an intrusion but as an expected condition of leadership. Over time, this produces steadier confidence and faster recovery after disruption.

The deeper truth: Flexibility is not about liking change; it is about being less ruled by it. Mental and behavioural rehearsal trains the nervous system to treat uncertainty as familiar terrain. By rehearsing, you convert anticipation into agency.

The more you practise responding before you must, the more resilient you become when life moves faster than your plans. True flexibility is not spontaneous chaos but disciplined readiness: a capacity to move with life rather than against it.

Scenario stretching

Rigid thinking often hides behind confidence in a single plan. Flexibility grows when you learn to hold multiple futures in mind without clinging to one. Scenario stretching is a way to practise this mental elasticity. It involves exploring a range of plausible outcomes for a situation and imagining how you would respond to each.

This is not about predicting the future but preparing for it. When leaders stretch their scenarios, they reduce shock and increase agility. They develop a habit of asking, “What else could be true?” and “How might I adapt if this happened?” This mental rehearsal strengthens emotional balance and decision-making under uncertainty.

Steps to take

1. Choose a live situation

Select a real situation that carries uncertainty. It might be a project with shifting timelines, a career transition, or a relationship at work that feels unpredictable. Choose something that genuinely matters to you and has several possible outcomes.

Why: Working with a live situation increases emotional engagement. Flexibility develops most when the stakes are meaningful, not abstract. When the brain senses relevance, it encodes learning more deeply and strengthens resilience pathways.

2. Create three plausible futures

Write three possible futures for this situation: one positive, one challenging, and one neutral. For example, success, setback, and steady progress. Avoid extremes such as “total failure” or “wild success.” Each scenario should feel realistic enough to imagine living through.

Why: Considering multiple outcomes trains cognitive flexibility. It helps prevent the brain’s tendency toward tunnel vision and catastrophic or idealised thinking. By holding several futures at once, you widen your field of awareness and reduce emotional volatility.

3. Identify your emotional and behavioural response to each

For each scenario, note your first emotional reaction and your likely behavioural response. For instance, would you feel relieved, defensive, inspired, or disappointed? Would you seek help, push harder, or disengage?

Why: Emotional anticipation is a form of preparation. Naming how you might feel in each case reduces the surprise and intensity when it happens. It also reveals your default coping patterns so that you can choose more constructive ones.

4. Design a resilient response

For each scenario, describe a deliberate action that reflects your best self, not just your automatic one. Ask, “How would a flexible version of me act here?” Keep each action specific and realistic.

Why: Flexibility is about maintaining agency when conditions change. By preparing adaptive responses in advance, you reduce decision fatigue and strengthen psychological readiness.

5. Extract the transferable insight

Step back and look across the three scenarios. What patterns do you see? What principle or value guides your best self in all three cases? This becomes your flexibility anchor.

Why: Reflection consolidates learning and builds meta-cognition, the ability to think about your thinking. Identifying what remains stable across change gives you a centre of gravity that prevents overreaction.

Examples

Organisational change: A leader preparing for restructuring writes three versions of the future: promotion, lateral move, or role loss. In each, she outlines how she will respond constructively. When the actual outcome lands somewhere in between, she feels grounded rather than shaken.

Career planning: An analyst considering two job offers writes possible futures for each. Instead of choosing based on fear of missing out, he recognises that his wellbeing depends more on autonomy than prestige.

Family situation: A parent anticipating a teenager’s exam results rehearses three responses: celebration, support, or calm encouragement. When the results are mixed, the parent is ready to respond with balance rather than anxiety.

Health challenge: Someone awaiting medical results explores three futures: clear, manageable, and difficult. Thinking through support systems for each outcome reduces dread and increases agency.

Variations

-

The 3–3–3 method: Three futures, three emotions, three adaptive responses.

-

Collaborative stretching: Ask your team to brainstorm three possible futures for a project and how they would adapt in each.

-

Journaling practice: At the end of each week, write a brief note about one situation that surprised you and how your response could have been more flexible.

-

Visual mapping: Draw each scenario as a branching path and label your reactions. Seeing the map helps distance emotion from event.

-

Time horizons: Stretch the same scenario over three timeframes: now, six months, and two years. Notice how your perspective changes.

-

Anchor phrase: Create a short sentence that captures your flexibility insight, such as “Adjust, do not resist.”

Why it matters: Scenario stretching strengthens both cognitive and emotional agility. Research in foresight and stress adaptation shows that people who mentally prepare for multiple outcomes experience less anxiety and greater resilience when change arrives (Bonanno, 2004). The mind treats imagined experience as partial exposure, lowering the stress response and improving composure under pressure.

Leaders who stretch their thinking this way make better strategic decisions. They avoid the traps of overconfidence and fatalism and maintain calm authority in volatile environments. By rehearsing possibilities, they expand not only their thinking but their capacity for grace under uncertainty.

The deeper truth: Flexibility is not the absence of plans but the capacity to move between them with integrity. Scenario stretching teaches that you can hold uncertainty without collapsing into fear or false certainty. The more comfortable you become with imagined futures, the less power change has over you.

True flexibility is not predicting what will happen but strengthening who you will be when it does.

Polarity mapping

Leaders often face situations where both sides seem right. Do you stay firm or adapt? Plan carefully or act quickly? Protect people or push for results? These are not simple choices. They are polarities: pairs of values that depend on each other for balance.

Treating polarities as problems forces you to choose one side and reject the other. Over time, this creates cycles of frustration and correction. Polarity mapping helps you see the full picture. It invites you to hold both truths at once and manage the rhythm between them. The goal is not compromise, but dynamic balance.

Steps to take

1. Name the polarity

Think of a current tension in your work or life that pulls you in two directions. Write it as a pair of words joined by “versus”. Examples include Structure versus Freedom, Confidence versus Humility, or Self-care versus Service. Both sides must be valuable.

Why: Clear naming turns confusion into understanding. When you see that both values hold merit, you move from “Which is right?” to “How can I honour both?” That small shift opens flexibility and reduces inner conflict.

2. Draw the map

On a page, divide a table into two columns. Label the left column with one pole and the right column with the other. Each column will include four sections: Positives, Negatives, Early Warnings, and Ways to Balance.

Why: Seeing both sides side-by-side externalises the tension. It transforms a feeling into a visible system. Writing clarifies what is really happening and prevents either side from dominating your thinking.

3. Identify the positives of each pole

Under each heading, list what happens when that value is expressed well. For example, Structure brings order, predictability, and clarity. Freedom brings creativity, autonomy, and energy. Write at least three points per side.

Why: This step builds appreciation. When you focus on the benefits of each value, you reduce bias toward your preferred style and begin to see how both sides serve you in different contexts.

4. Describe the negatives of each pole

List what happens when each value is taken too far. Too much structure may become rigidity or control. Too much freedom may lead to confusion or inconsistency.

Why: Overuse turns strengths into liabilities. Naming the risks helps you recognise when your default tendency begins to harm rather than help. Awareness of limits makes flexibility real, not theoretical.

5. Note early warning signs

Reflect on the first hints that you are leaning too far to one side. This might be an emotional cue like irritation or fatigue, or a behavioural sign like micromanaging, avoiding structure, or delaying decisions.

Why: Early awareness prevents extremes. When you can see drift beginning, you can adjust before the imbalance grows. Leaders who notice subtle signs can restore balance calmly rather than reactively.

6. Plan ways to balance

For each side, write practical actions that help you rebalance when you notice drift. If you lean toward Structure, you might schedule open time for exploration. If you lean toward Freedom, you might set short planning rituals.

Why: Balance is maintained through small, regular actions. Rebalancing is not about fixing mistakes but sustaining movement between two strengths. Each action becomes a signal that both values matter.

Examples

Decision-making: A leader torn between Speed versus Inclusion maps both sides. They see that quick decisions maintain momentum but sometimes miss key perspectives. They add a short consultation step before final calls, keeping pace without losing input.

Self-management: A manager lists Control versus Trust as a polarity. They notice that over-control brings exhaustion and resentment. Scheduling one day each week for delegation experiments helps restore balance and confidence in others.

Personal wellbeing: Someone maps Self-care versus Service. They realise that giving too much drains their energy and limits generosity. Protecting small moments for rest makes their service more sustainable and joyful.

Leadership style: A senior leader struggles between Confidence versus Humility. Mapping reveals how each supports the other. Practising humility through listening rounds out confidence with credibility.

Variations

-

Reflection journal: Map one personal polarity each month and revisit it to see what changed.

-

Morning check-in: Ask, “Which side am I overusing today?” to reset before the day begins.

-

Mindful practice: Use breathing or journaling to pause when tension rises between the poles.

-

Polarity cards: Keep short reminders of your top three recurring polarities in your notebook.

-

Quarterly reset: Choose one polarity that has drifted too far and intentionally rebalance it for a week.

-

Growth focus: Notice whether your polarities tend to be about control, pace, care, or identity. Patterns reveal growth edges.

Why it matters: Polarity mapping trains the mind to think in systems, not sides. Leaders who can hold opposing values are more adaptive, creative, and emotionally steady. Research on paradoxical leadership shows that the ability to manage tension predicts both resilience and performance (Smith and Lewis, 2011).

By practising this, you reduce the need to defend one view. You become more responsive, less reactive, and more at ease in uncertainty. The habit of mapping builds awareness of how your behaviour swings under pressure, allowing you to adjust with intention.

The deeper truth: Most inner conflict comes from misunderstanding tension as opposition. Polarity mapping shows that life’s best choices are rarely either/or. They are usually both/and. Flexibility grows when you stop trying to eliminate tension and start working with it.

Over time, you will notice patterns: the same polarities returning in different forms. Each appearance is an invitation to refine balance and deepen maturity. The goal is not perfect symmetry but conscious movement. You learn to navigate contradictions with calmness rather than control.

When you can stand in the middle of a polarity with awareness, you discover something powerful: wisdom often lives between the poles, not at the extremes.

Flexibility diary

Sustaining flexibility is less about dramatic change than about noticing and refining small adjustments over time. Like a muscle, adaptability strengthens through deliberate repetition. The flexibility diary is a way to build that habit. It turns reflection into practice and gives you a way to see your patterns of resistance and release.

This exercise helps you track how you respond when routines shift, plans derail, or others behave unpredictably. By recording and revisiting these moments, you learn what anchors you and what triggers rigidity. Over time, this awareness creates a form of emotional elasticity: the ability to recover balance without forcing control or losing direction.

Steps to take

Step 1: Capture the moments

At the end of each day or week, note one or two situations where something did not go as planned. Record what happened, how you felt, and what you did next. Keep the description simple and factual, like a short field note.

Why: Capturing events quickly helps bypass rationalisation. It allows you to see flexibility as it happens rather than as you later justify it.

Step 2: Name your response

Under each entry, label your immediate reaction: did you resist, adapt, withdraw, or overcompensate? Note what emotion was most active such as frustration, fear, confusion, curiosity, or calm. Then take a moment to reflect using these guiding questions:

-

What emotion was strongest in that moment?

-

What was I trying to protect or preserve?

-

Did I react automatically or make a conscious choice?

-

What part of my response helped me stay effective?

-

What part limited my ability to adapt?

Why: Naming emotional patterns turns vague discomfort into data. These questions reveal not only what you felt but why you reacted that way. Over time, this builds self-awareness of your flexibility triggers and habits, helping you move from instinctive reaction to deliberate response.

Step 3: Extract the lesson

Ask yourself: What was my intention? What helped or hindered adaptation? What might I do differently next time? Keep this reflection to a few sentences, focusing on insight rather than self-criticism.

Why: Reflection transforms experience into learning. By distilling one insight at a time, you gradually train your emotional agility.

Step 4: Identify recurring themes

After several entries, review your notes for repetition. Do you struggle more with ambiguity, control, or pace? Do you adapt more easily when others are calm or when you feel prepared?

Why: Seeing your patterns across time helps reveal the deeper conditions that support or undermine your flexibility. It turns self-observation into self-management.

Step 5: Design micro-adjustments

From your observations, choose one theme to work on for the next week. It might be “pause before replying,” “ask one more question before deciding,” or “reframe unexpected changes as learning opportunities.” Write your chosen practice at the top of your next diary page and track small shifts as they occur.

Why: Flexibility grows from iteration. Choosing one micro-adjustment focuses effort, builds confidence, and turns reflection into forward motion.

Examples

Leadership reflection: A department head notices that she grows impatient whenever meetings drift off agenda. Reviewing her diary, she realises her frustration stems from a need for control rather than lost time. She experiments with allowing five minutes of open discussion before redirecting. Engagement improves and her tension eases.

Project delivery: A software lead finds that unexpected client feedback often triggers defensiveness. By tracking these moments, he learns that asking clarifying questions before responding helps him regain calm. Within weeks, his tone shifts from reactive to collaborative.

Personal adaptation: After keeping a flexibility diary for a month, a consultant sees that fatigue often narrows her perspective. She begins scheduling short walks between meetings and notices she can adjust more easily when rested.

Variations

-

Weekly reflection ritual: Dedicate 15 minutes each Friday to write, review, and set your next micro-adjustment.

-

Trigger tracker: Focus on one domain, such as changes in plans or feedback, and record only those instances.

-

Morning preview: At the start of the day, identify one situation that might require flexibility and note how you will handle it.

-

Pair sharing: Exchange flexibility diaries with a trusted peer once a month to compare insights and support accountability.

-

Quarterly synthesis: Review your diary every three months to map growth and identify persistent rigid zones.

-

Mind-body integration: Combine journaling with a short mindfulness or breathing practice to reinforce self-regulation.

Why it matters: Flexibility is not about liking change but learning how to stay composed within it. People who deliberately reflect on moments of disruption develop stronger emotional range and cognitive agility. Research on emotional regulation shows that repeated self-observation increases adaptive coping and reduces stress reactivity (Gross, 2002). Keeping a diary strengthens metacognition—the awareness of how you think—making you less hostage to automatic reactions and more able to choose your response.

Over time, this practice builds what psychologists call psychological flexibility: the ability to stay aligned with your values even when circumstances shift. It is one of the strongest predictors of wellbeing and performance under pressure.

The deeper truth: The opposite of flexibility is not firmness but fear. Rigidity often disguises the wish to avoid uncertainty or loss of control. By making these reactions visible, the diary transforms them into material for growth. You begin to see that adaptability is not about becoming shapeless or compliant but about remaining steady while adjusting form.

Leaders who practise flexibility as reflection rather than reaction model calm under change. They show that steadiness and openness can coexist. The flexibility diary is a small tool for a large skill: staying centred when the world moves.

Conclusion: The art of staying open

Flexibility is not about being indecisive or easily swayed. It is about staying open to what is changing while remaining anchored in what matters. It is the discipline of adjusting thought, emotion, and behaviour without losing direction. Within that balance lies the foundation of resilience, creativity, and learning.

The practices in this section are designed to expand that balance. They invite you to pause, reframe, and experiment. Whether through pattern interruption, perspective shifting, or polarity mapping, each exercise helps you notice where rigidity shows up and how openness can replace it. Together, they build the capacity to move with change rather than resist it.

This matters because inflexibility quietly limits growth. When we cling to certainty, we stop listening. When we overvalue control, we lose perspective. In fast-moving environments, these habits erode innovation and slow response. Leaders who cannot adapt risk becoming reliable but irrelevant. Flexibility keeps awareness alive, allowing curiosity to coexist with conviction.

Flexibility also protects wellbeing. Leaders who can release old views and recover from disruption conserve emotional energy. They navigate ambiguity without panic and adapt their tone and style without losing authenticity. Teams led by such individuals learn to view change not as threat but as opportunity.

In the end, flexibility is not about compromise; it is about evolution. It turns uncertainty into insight, change into movement, and contradiction into learning. It asks a quiet question that keeps leadership alive: What else might be true here?

Reflective questions

Where in your work do you notice yourself resisting change or holding tightly to control?

What assumptions make it hard for you to adjust direction once a plan is in motion?

When was the last time you learned something by letting go of being right?

How do you respond when others suggest different ways of working?

What small experiments could help you expand your comfort with uncertainty?

Flexibility is the hinge between stability and growth. It allows leaders to stay responsive, curious, and steady at the same time. When you practise it, you turn complexity into creativity and adaptability into strength.

Do you have any tips or advice on flexibility?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Flexibility is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Stress Tolerance and Optimism in the Stress Management facet.

Sources:

Bar-On, R. and Parker, J. D. A. (2000). The Handbook of Emotional Intelligence: Theory, Development, Assessment, and Application at Home, School, and in the Workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291.

Kashdan, T. B. and Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Martin, M. M. and Rubin, R. B. (1995). A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychological Reports, 76(2), 623–626.

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualisation of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

Stein, S. J. and Book, H. E. (2011). The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. 3rd ed. Mississauga: Jossey-Bass.

Weick, K. E. and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2015). Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Leave A Comment