Why do we spend so much of our lives in rooms deciding things that do not matter? The calendar fills with gatherings framed as essential, yet many produce little more than postponed choices and diluted responsibility. The ritual of meeting is comforting: it gives the appearance of progress, spreads accountability, and reassures us that we are “being thorough.”

Yet this reassurance is expensive. Each hour spent in a meeting is an hour not spent serving customers, testing new ideas, or building. Worse, meetings often signal a culture where authority is withheld and trust is conditional. We gather everyone because we cannot imagine letting someone else decide.

As I wrote in my piece on decision rights and effective meetings, much of this comes down to unclear ownership. When it is not clear who holds the right to decide, the default is to pull people into the room.

The trap of over-decisioning

Jeff Bezos observed that not all decisions are equal. In his 2015 letter to shareholders he wrote:

“Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible — one way doors — and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and do not like what you see on the other side, you cannot get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions.”

He contrasted this with a second type:

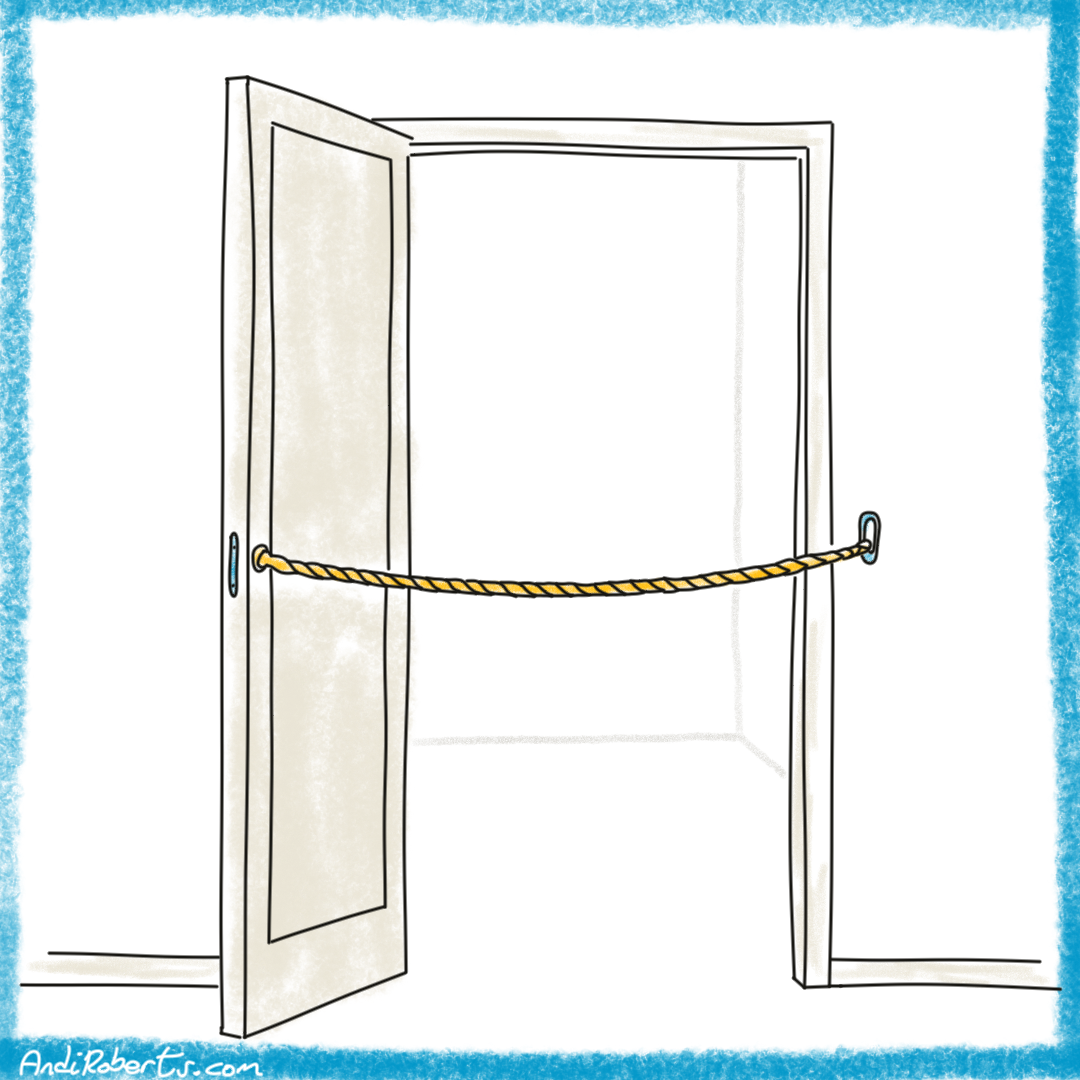

“But most decisions are not like that — they are changeable, reversible — they are two way doors. If you have made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you do not have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.”

The trap is that organisations, especially as they grow, drift toward treating all decisions as Type 1. Bureaucracy, compliance fears, and risk-averse cultures push leaders to over-process even trivial, reversible choices. A simple product tweak or policy change can trigger layers of approval, multiple decks, and endless meetings. In this way, the culture confuses process with prudence.

Consider the difference: approving the acquisition of another company is a one way door. Once signed, it cannot be undone. By contrast, changing the colour of a button on your website to see if it increases customer clicks is a two way door. If it fails, you simply change it back. Both matter, but they do not deserve the same weight of process.

The cost of slow decision making

The cost of over-decisioning is measured in more than time. Strategy scholars such as Kathleen Eisenhardt have shown that fast decision-making is strongly correlated with high-performing, adaptive organisations. Delays sap not only speed to market but also morale. When employees sense that initiative will be second-guessed or stalled in endless meetings, they stop proposing bold ideas.

There is also a psychological cost. Meetings designed to contain risk often contain people instead. They implicitly say: We do not trust you to act alone. We do not trust that mistakes can be corrected. We do not trust the system to learn. The result is a cycle of dependency. People wait for permission rather than acting with judgment.

Trust, once eroded, leads to disengagement. Leaders begin to complain that people lack initiative, without recognising that initiative has been systematically stripped away by decision processes that infantilise rather than empower.

Rethinking decision ownership

The first step toward reclaiming time is not cancelling meetings but clarifying ownership. Meetings should be for the few truly irreversible choices that require collective wisdom. Everything else belongs closer to the action.

Categorising decisions explicitly is a discipline that keeps organisations honest. Is this a one way door or a two way door? What would actually happen if we were wrong? What is the cost of reversal? When leaders force these questions into the open, they often discover that many issues do not merit collective attention.

Bezos reminded leaders in 2016: “Never use a one size fits all decision making process. Many decisions are reversible, two way doors. Those decisions can use a lightweight process.” Lightweight does not mean careless. It means speed with accountability. It means empowering those who hold the knowledge and are nearest to the consequences.

This shift requires courage not from the deciders, but from leaders who must let go of control. To delegate a decision is to extend trust. It is to believe that authority grows when shared, not when hoarded.

A practice of discernment

Good judgment comes from asking the right questions before mobilising collective time. Useful tests include:

-

Is this decision reversible: If the answer is yes, then speed matters more than consensus. A decision that can be undone is better treated as an experiment than as a final judgment, because the organisation learns by acting rather than debating.

-

What is the real cost of being wrong: Many meetings exaggerate the potential downside. By honestly examining the true risks, we often discover that most errors are low-cost and correctable, making the case for faster action. This reframes mistakes not as failures but as investments in learning.

-

Who has the most relevant knowledge: Decision-making quality improves when authority rests with those closest to the facts. This reduces distortion, cuts out unnecessary layers of approval, and increases ownership of the outcome. It also creates a culture where expertise is valued over hierarchy.

-

How can we experiment our way forward rather than debate our way forward: Pilots and prototypes create clarity faster than prolonged discussion. A small test, launched quickly, often answers questions that no meeting could settle with certainty. This experimental posture builds resilience, because the organisation becomes skilled at adapting instead of over-analysing.

For example, deciding whether to launch a new global product line is a one way door , it requires investment, branding, and long-term commitment. Deciding whether to trial a new project management app within one team is a two way door , if it fails, you can drop it within weeks with little harm.

Bezos also offered a pragmatic rule of thumb: “Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you are probably being slow.”

This advice challenges a cultural reflex: the desire for certainty. Organisations often seek the perfect decision, yet progress is usually found in iteration. Deciding with 70% is not about recklessness. It is about choosing learning over paralysis.

The new meaning of meetings

If most decisions are two way doors, then meetings can be liberated. They no longer need to carry the weight of every operational choice. Instead, meetings can be redefined as spaces for:

-

Confronting the few one way doors that truly shape the future: These are the moments that justify bringing people together: strategic choices, culture-defining commitments, or investments that cannot easily be reversed. Giving them the time and attention they deserve restores weight to the act of gathering. When people know that meetings are for the decisions that matter most, they show up with sharper focus and greater seriousness.

-

Aligning people around values and direction rather than minor tactics: When meetings focus on shared purpose instead of micromanaging detail, participants leave with clarity and energy. This creates coherence across teams without stripping away their autonomy. The conversation shifts from “what should we do this week” to “why do we exist and how do our actions fit into that larger picture.”

-

Building relationships and trust, which reduce the need for control later: Meetings can be a place to strengthen the human fabric of an organisation. Stronger relationships make it easier to delegate decisions because trust has already been built, lowering the impulse to centralise control. Time spent connecting at a deeper level pays dividends in reduced oversight later.

When meetings serve this higher purpose, they regain vitality. They become places where people want to show up because the conversation matters. And when authority is pushed outward, the organisation moves faster, people feel trusted, and collective time is spent on what truly deserves it.

This is where the insights from the leadership library on planning are useful. Thoughtful planning and foresight keep many issues from spilling into meetings, leaving room for conversations that genuinely need us. A worthwhile follow-on read is the Waterline principle developed at W.L.Gore.

An invitation to decide differently

The next time you feel compelled to schedule a meeting, pause. Ask yourself: Is this a one way door or a two way door? What is the smallest group who could act with judgment? What would happen if we trusted them to decide?

If we reclaimed half the hours lost to over-decisioning, what could we create with that time? What new products, services, or ideas could flourish? What trust might be built if we treated people as decision-makers rather than as participants in endless discussions?

Decisions are doors. Some require us to walk together with care. Most allow us to step through lightly and return if needed. Wisdom lies in knowing the difference, and courage lies in trusting others to walk through.

Do you have any tips or advice on effective decision-making & meetings?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

References

Amazon.com, Inc. (2015) 2015 Letter to shareholders. Available at: https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/annual/2015-Letter-to-Shareholders.PDF (Accessed: 24 September 2025).

Amazon.com, Inc. (2016) 2016 Letter to shareholders. Available at: https://ir.aboutamazon.com/annual-reports-proxies-and-shareholder-letters/default.aspx (Accessed: 24 September 2025).

Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989) ‘Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments’, Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), pp. 543–576. Available at: https://assets.super.so/6b4b5d92-904a-4e7b-95bd-914dd1d1528f/files/d3e001de-5bf0-4c34-8230-9eec106a9339/Eisenhardt_1989_Making_fast_strategic_decisions_in_high-velocity_environments.pdf (Accessed: 24 September 2025).

Roberts, A. (2025.) Decision rights and effective meetings. Available at: https://andiroberts.com/leadership-questions/decision-rights-effective-meetings (Accessed: 24 September 2025).

Roberts, A. (2025) Leadership library: planning (tab). Available at: https://andiroberts.com/leadership-library (Accessed: 24 September 2025).

Leave A Comment