We live in a culture that often confuses politeness with silence and power with domination. Many of us are taught early that it is better to fit in than to speak up, or that strength means pushing until others yield. Between these extremes of compliance and aggression lies a quieter, harder path: assertiveness.

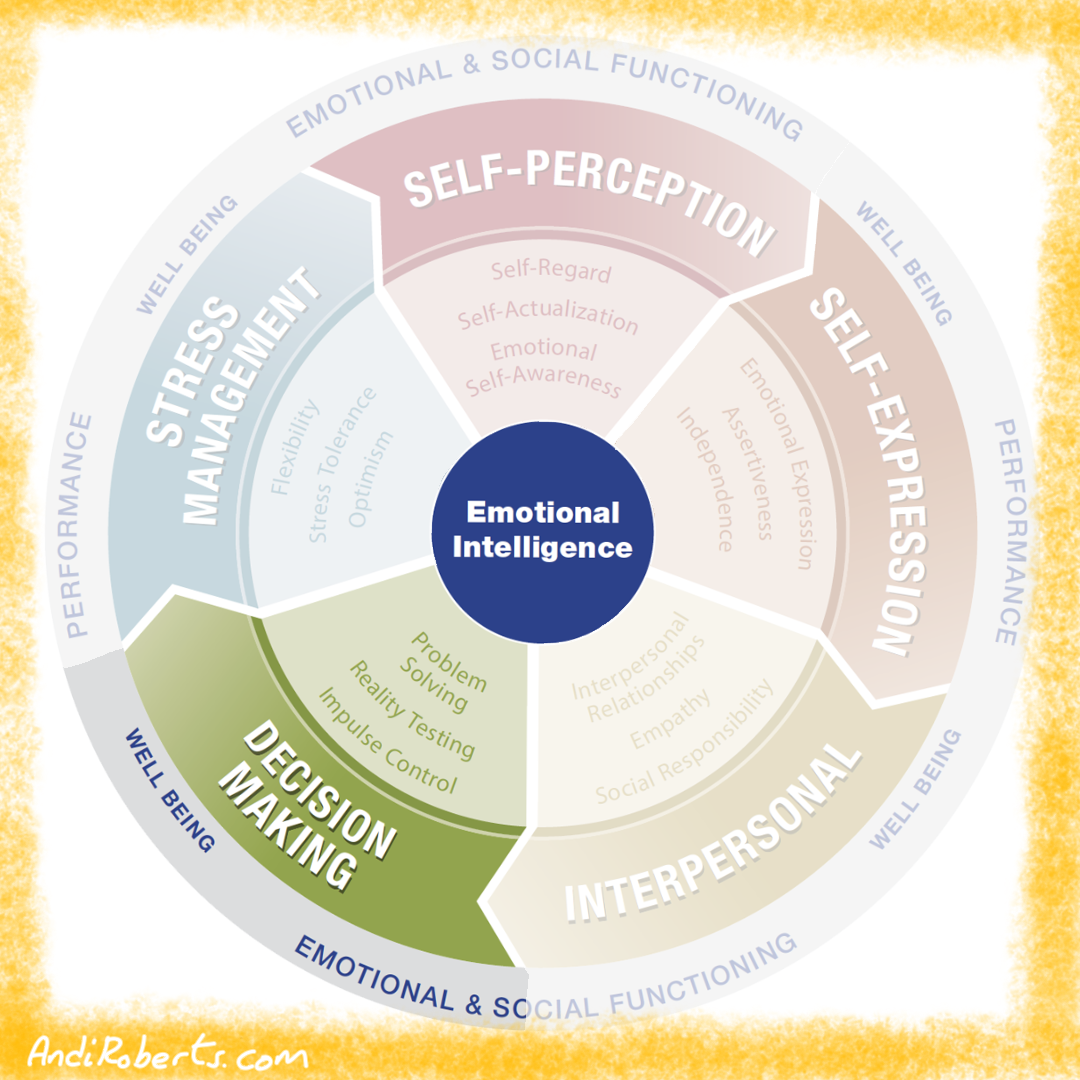

In the EQ-i model, assertiveness is defined as the ability to express feelings, beliefs, and needs openly, while respecting those of others (Stein & Book, 2011). It is not about overpowering or persuading, nor about withdrawing to keep the peace. It is about bringing your voice into the room with clarity and without apology, while still making space for others to do the same.

The absence of assertiveness carries familiar costs. When people avoid voicing their needs, frustration accumulates and relationships strain. Requests pile up unanswered until resentment leaks out through sarcasm, withdrawal, or quiet disengagement (Linehan, 1993). Teams where assertiveness is lacking often suffer from unspoken conflicts and uneven workloads. On the other side, when assertiveness tips into aggression, collaboration collapses into competition and trust evaporates.

The presence of healthy assertiveness, by contrast, builds strength into relationships. Research shows that assertive communication is linked to reduced stress, clearer problem-solving, and higher satisfaction in both personal and professional contexts (Speed et al., 2018). Leaders who practise it can set boundaries without hostility, raise concerns without blame, and invite accountability without fear. Colleagues who practise it can decline requests, ask for support, and name tensions, not to win, but to create understanding.

Why assertiveness matters

If assertiveness is the ability to voice needs respectfully, the question is: why does it matter? Why risk discomfort when silence is easier?

Resilience under pressure

Unspoken needs rarely disappear; they intensify. Suppressing them leads to stress and burnout. Assertiveness provides a release valve. A manager who says, “I cannot take this on without more resources,” prevents overload before it becomes crisis.

Better decision-making

Decisions suffer when the voices at the table are muted. Assertiveness ensures that concerns, perspectives, and boundaries surface, making choices more accurate and sustainable. Research on group dynamics shows that diverse input improves outcomes, but only when people feel safe to contribute (Edmondson, 1999). Assertiveness is how that safety becomes visible.

Stronger relationships and leadership

Relationships built on avoidance are fragile; those built on openness are resilient. Assertive leaders who say, “I need us to stay respectful in this discussion,” or “I feel confident this direction fits our values,” signal honesty without aggression. This builds trust because others know where they stand.

A foundation skill: In the EQ-i framework, assertiveness is not an optional trait but a foundation for emotional intelligence. It underpins independence, stress tolerance, and empathy. Without it, boundaries blur, values go unspoken, and teams falter. With it, individuals and groups can hold both voice and respect together.

Eight practices for building assertiveness

Like any dimension of emotional intelligence, assertiveness is not learned by theory alone. It is built through practice, in the daily choices of whether to stay silent or to speak, to defer or to declare, to avoid or to engage.

The eight exercises that follow offer different entry points. Some focus on inner clarity, like identifying your rights or mapping your boundaries. Others train expression in the moment, like practising “no” or using structured dialogues. Still others expand the field into relationships, like contracting agreements or rehearsing listening as an assertive act.

Each exercise is structured in the same way:

- Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

- Steps guide you through the process.

- Examples show it in real contexts.

- Variations suggest ways to adapt.

- Why it matters grounds the practice in research and insight.

These practices are not about control but about choice. They allow you to voice your needs without apology and to hear others without fear. Assertiveness, in the end, is not simply a skill. It is a stance of dignity: to speak with honesty, to listen with respect, and to create agreements where both sides can stand tall.

Exercise 1: Assertive rights reminder

Many of us struggle with assertiveness because we carry unspoken rules about what is allowed. Saying no feels rude. Stating a preference feels selfish. Asking directly for what we need feels demanding. These beliefs are rarely challenged, yet they quietly shape how much of our voice we bring into relationships and work.

Assertiveness begins not with technique but with permission. Psychologists Alberti and Emmons (2008) describe assertiveness as acting in ways that respect both your own rights and the rights of others. Yet for many people, the first hurdle is recognising that you have those rights in the first place.

Reminders such as “I have the right to say no without guilt” or “I have the right to express my feelings honestly” sound simple. In practice, they can feel radical. Naming your rights explicitly builds an inner foundation for assertive action. It anchors the belief that your needs are legitimate, that your voice has value, and that boundaries are not selfish but necessary.

Steps

- Write your rights

Begin by listing core assertive rights, such as:

-

- I have the right to say no without guilt.

- I have the right to express my feelings and opinions.

- I have the right to make mistakes and learn from them.

Why: Writing them makes them tangible and harder to dismiss as “just ideas.”

- Choose one right per day

Each morning, select one right to practise. For example: “Today I will practise my right to ask for help when I need it.”

Why: Focusing on one right creates clarity and avoids overwhelm.

- Notice opportunities

As the day unfolds, pay attention to situations where that right is relevant. For example, when someone interrupts, remember your right to finish speaking.

Why: Awareness creates the bridge between belief and behaviour.

- Act on the right

Practise voicing the right in real time. For instance: “Please let me finish my thought” or “No, I cannot take that on right now.”

Why: Small, concrete actions reinforce the legitimacy of the right.

- Reflect each evening

At the end of the day, ask: Did I act on this right? How did it feel? How did others respond? What did I learn?

Why: Reflection consolidates learning and prepares you to practise the next right.

Workplace examples

- An employee remembers: “I have the right to ask for clarification.” In a confusing meeting, instead of staying silent, they ask: “Could you explain the next steps more clearly?” The request prevents mistakes and builds confidence.

- A manager recalls: “I have the right to delegate work appropriately.” When overloaded, she says: “I need your support on this task so we can meet the deadline.”

Personal examples

- A friend remembers: “I have the right to say no without guilt.” When invited to a social event they do not want to attend, they reply: “Thank you for inviting me, but I won’t be coming tonight.”

- A parent recalls: “I have the right to ask for help.” Instead of silently coping, they ask their partner: “Could you take over bedtime tonight? I need a rest.”

Variations

- Pocket card: Write your top five rights on a small card and keep it with you. Review before meetings or conversations.

- Digital reminders: Set a phone reminder with one right each morning.

- Buddy system: Share your chosen right with a colleague or friend. Check in at the end of the day about how you practised it.

- Weekly theme: Focus on one right for an entire week, testing it in different settings.

Why it matters: Research shows that assertiveness is associated with greater self-esteem, reduced anxiety, and stronger relationships (Speed et al., 2018). Yet without an inner belief that your needs are valid, no technique will stick. Assertive rights act as cognitive anchors. They shift assertiveness from something you “should” do to something you are entitled to do.

The deeper truth: Assertiveness is not only about what you say. It is about what you believe you are allowed to say. If you secretly believe that your needs are less important, your voice will hesitate. By reminding yourself daily of your rights, you reshape that belief. Assertiveness then stops feeling like defiance and starts feeling like dignity.

Exercise 2: The daily assertiveness tracker

Many people assume they are “reasonably assertive” until they start looking closely at their daily interactions. What we intend and what we communicate are often two different things. We think we are being clear, yet our tone is hesitant. We think we are being polite, yet we are actually avoiding. We think we are being firm, yet our words come out as bluntness. Without a way to see these patterns, they remain invisible.

Behavioural research shows that self-monitoring is one of the most effective tools for changing habits (Michie et al., 2009). When we record our actions, we move from vague impressions to specific evidence. A food diary reveals unconscious snacking. A spending log reveals hidden costs. An assertiveness tracker reveals communication habits that either build or erode confidence.

This exercise invites you to create a daily practice of noticing when you were passive, assertive, or aggressive. By logging these moments and reflecting on them, you develop a clear picture of your style. Over time, the tracker becomes not only a mirror but a guide, showing you exactly where you can practise small shifts toward healthier assertiveness.

Steps

- Create your tracker

Draw a simple table with four columns: Situation, Your response, Style (Passive, Assertive, Aggressive, Unsure), and Reframe.

Why: Structure makes it easy to capture the essence of interactions quickly, preventing avoidance.

- Record key moments each day

At the end of the day, jot down 3–5 interactions where assertiveness was relevant. For example, a colleague asked for help, a manager gave feedback, or a friend made a request.

Why: Daily capture reduces memory bias and builds a reliable dataset of your habits.

- Label your style honestly

Classify your response:

-

- Passive: Did not express needs, avoided, gave in.

- Assertive: Stated needs clearly and respectfully.

- Aggressive: Imposed, dismissed, or dominated.

- Unsure: Mixed signals, or cannot tell.

Why: Naming the style helps you see patterns that are usually hidden by rationalisations.

- Choose one unassertive moment

Select one passive or aggressive interaction from the day. Write down how you might have reframed it assertively using NVC (Observation–Feeling–Need–Request) or DESC.

Why: Focusing on one moment at a time turns reflection into action and avoids overwhelm.

- Review weekly

At the end of the week, review your tracker. Look for themes: Are you more passive with authority figures? More aggressive under time pressure?

Why: Awareness of triggers prepares you to plan more intentional responses.

Workplace examples

- The silent meeting: An analyst stays quiet in a meeting despite having useful input. Tracker entry: Passive. Reframe: “I’d like to add a point here because it could affect the outcome.”

- Overloaded with tasks: An employee says yes to a new assignment even though their schedule is full. Tracker entry: Passive. Reframe: “I cannot take this on right now without dropping other priorities. Could we revisit timing?”

- Snapping under stress: A manager responds to a late report with irritation. Tracker entry: Aggressive. Reframe: “I’m frustrated because timeliness matters. Let’s agree on a system to avoid delays.”

Personal examples

- Friend’s choice: A friend chooses a film you dislike. You say nothing. Tracker entry: Passive. Reframe: “I’d prefer a different movie — could we pick one together?”

- Family boundary: A relative criticises your parenting style. You respond sharply. Tracker entry: Aggressive. Reframe: “I hear your concern, and I’m choosing a different approach because it aligns with my values.”

- Household chores: You quietly resent a partner for not doing dishes. Tracker entry: Passive. Reframe: “I feel tired when the dishes pile up. Could we agree to share them more evenly?”

Variations

- Traffic light system: Mark each interaction with colours: red for passive, yellow for aggressive, green for assertive. The visual makes patterns obvious.

- Buddy check: Share one tracker entry a week with a friend, coach, or colleague. Ask how they might have reframed it assertively.

- Digital tracker: Use a notes app or journaling app. Create a template with Situation–Response–Style–Reframe for quick entries.

- Focus theme: Choose one recurring pattern (e.g. difficulty saying no to managers) and track it specifically for a week.

Why it matters: Research on habit change is clear: what gets measured gets improved. A daily assertiveness tracker shifts communication from instinct to intentionality. By noticing the gap between how you responded and how you could have responded, you develop a sharper sense of choice. Over time, this practice rewires your default responses. Instead of collapsing into passivity or tipping into aggression, you gain confidence in choosing assertive, respectful clarity.

The deeper truth: Assertiveness is not built in dramatic moments. It grows in the ordinary exchanges of each day, in whether you speak or stay silent, whether you agree or decline, whether you snap or pause. The tracker makes those moments visible. Each time you notice and reframe, you reclaim a little more freedom to live by choice rather than habit. Assertiveness then becomes less about a single skill and more about a way of inhabiting your relationships with honesty and respect.

Exercise 3: Assertive listening

When people think of assertiveness, they often think only about speaking up, saying no, making requests, standing their ground. Yet listening is just as critical. Many conflicts escalate not because the initial message was unclear, but because each person felt unheard. Assertive listening is the practice of fully hearing another’s perspective while still making space for your own.

Psychologist Carl Rogers (1957) described “active listening” as one of the most powerful tools for building trust. Assertive listening goes a step further: it is active listening with boundaries. You demonstrate respect for the other person’s experience, but you do not collapse your own voice in the process. Instead, you listen first, reflect what you heard, then state your needs clearly.

This practice helps you avoid two common traps. Passive listeners nod silently but never bring their own view. Aggressive listeners interrupt or dismiss, escalating tension. Assertive listening offers a middle path: it acknowledges the other person, then adds your truth.

Steps

- Pause to receive

When someone speaks, resist the urge to prepare your rebuttal. Focus fully on their words.

Why: True listening reduces defensiveness and signals respect.

- Reflect back what you heard

Paraphrase their main point: “So you’re worried about deadlines and need faster updates, is that right?” Why: Reflection shows understanding and reduces the chance of misinterpretation.

- Acknowledge feelings

Name the emotion you hear beneath their words: “I hear frustration.” Why: Recognition validates the speaker and lowers tension.

- Insert your perspective

Once you’ve acknowledged them, state your own view: “I also need time to ensure accuracy, so rushing may create errors.” Why: This balances respect with self-expression, the essence of assertiveness.

- Seek a joint solution

Ask: “How can we balance timely updates with the need for accuracy?”

Why: Moving toward solutions shifts the tone from opposition to collaboration.

Workplace examples

- Team conflict: A colleague says, “You never update me.”Assertive listening: “I hear that you feel left out of the loop. I also need focused time without interruptions. Can we set a weekly update meeting?”

- Manager feedback: A boss criticises a report as incomplete.

- Assertive listening: “I hear that the level of detail was not what you expected. I also need clearer guidelines on what to include. Could we set those for the next report?”

Personal examples

- Friendship tension: A friend says, “You’re always too busy for me.”Assertive listening: “I hear that you feel neglected. I also need to balance work and rest. Can we plan one fixed evening together each month?”

- Family dispute: A teenager says, “You don’t trust me.”Assertive listening: “I hear that you feel controlled. I also need to know you’re safe. Can we agree on clearer check-ins?”

Variations

- Practice round: Role-play with a partner. One person complains, the other practises reflecting then asserting. Switch roles.

- Silent listening: Spend a full minute listening without interruption before reflecting back.

- Positive listening: Use the same structure to respond to praise: “I hear that you appreciated my help. I also enjoyed working together. Let’s keep doing that.”

- Written version: In emails, begin by acknowledging the other’s concern before stating your own need.

Why it matters: Research shows that feeling heard reduces defensiveness and increases willingness to collaborate (Weger et al., 2014). Assertive listening prevents conversations from becoming battles of competing monologues. By first acknowledging the other, you create space for your own voice to land with less resistance. This balance strengthens both relationships and outcomes.

The deeper truth: Assertiveness is not a tug-of-war where only one voice matters. It is a dialogue where both can be honoured. Listening does not weaken your stance; it strengthens it. When you acknowledge the reality of another person and then state your own truth, you shift the dynamic from opposition to mutual respect. Assertive listening reminds us that dignity is not won by shouting louder but by ensuring every voice, including your own, is clearly heard.

Exercise 4: The 3-second pause

Assertiveness is often lost in the split second between stimulus and response. Someone makes a request, interrupts you, or criticises your work, and before you know it you’ve already said yes, fallen silent, or snapped back. What happens in that instant often determines whether you act with clarity or with regret.

Viktor Frankl (1946) famously wrote that “between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response.” The 3-second pause is a way of reclaiming that space. It is a micro-practice: before you answer, breathe and count to three. This simple act disrupts autopilot and creates a moment to choose assertiveness over passivity or aggression.

Neuroscience research shows that even a brief pause activates the brain’s prefrontal cortex, shifting us from reactive patterns toward more deliberate decisions (Lieberman et al., 2007). The pause is not hesitation or weakness. It is strategy. It allows you to speak with composure, not compulsion.

Steps

- Notice the trigger

Pay attention to moments where you feel pressured — a request, a criticism, a sudden demand.

Why: Awareness of triggers is the first step to breaking automatic patterns.

- Pause for three seconds

Before responding, take a slow breath and silently count “one, two, three.”

Why: This interrupts reflexive reactions and buys time for choice.

- Check your intention

In the pause, ask: “Do I want to be clear? Do I want to be respectful?” Why: Reminding yourself of your goal increases the chance of an assertive, balanced response.

- Choose your words deliberately

Respond with a statement that is specific, clear, and respectful: “I cannot take this on right now” or “Please let me finish my thought.”

Why: Deliberate language reinforces the pause’s purpose: moving from impulse to intention.

- Reflect afterwards

After the interaction, notice how the pause affected your response and the other’s reaction.

Why: Reflection consolidates learning and increases the chance of pausing again in future.

Workplace examples

- The pressured yes: A manager asks you to stay late. Normally you blurt “okay.” This time you pause, breathe, and say, “I cannot stay tonight, but I can adjust my schedule tomorrow.”

- The heated meeting: A colleague interrupts you. Instead of snapping back, you pause, then say, “Please let me finish and then I’ll hear your point.”

Personal examples

- Family request: A relative pushes you to host an event. You pause before answering, then say, “I appreciate being asked, but I am not able to host this time.”

- Friend’s criticism: A friend says, “You’re always late.” Instead of defending instantly, you pause and respond, “I hear that this frustrates you. I’ll make more effort, but I’d also like us to plan start times realistically.”

Variations

- Silent breath: For especially tense moments, extend the pause to a full breath in and out before responding.

- Physical anchor: Touch your hand to your desk or clasp your fingers as a signal to pause.

- Written pause: In emails or texts, wait three minutes before replying when you feel triggered.

- Team practice: Invite your team to adopt the pause collectively in meetings, normalising slower and more thoughtful responses.

Why it matters: Many regretted responses, the hasty yes, the sharp retort, the awkward silence, come from reacting too quickly. The 3-second pause inserts choice into the gap between stimulus and response. It strengthens self-control, reduces emotional hijacking, and creates space for clarity. Research shows that even brief reflection improves decision-making and emotional regulation (Lieberman et al., 2007).

The deeper truth: Assertiveness is not about speed. It is about presence. The pause is a reminder that you do not have to give your power away to the urgency of the moment. In three seconds you can reclaim the space to decide, to speak with clarity, and to honour both yourself and the other. Over time, the pause becomes less a technique and more a way of living, responding to life not in haste but with intention.

Exercise 5: Assertive communication skills

Assertiveness lives in language. It is not only whether you speak but how you speak. Many people unintentionally weaken their voice through the words they choose: “I’m sorry to bother you,” “I just wanted to ask,” “Maybe we could…” These phrases soften the impact but also signal doubt. Others swing the opposite way, using blunt or forceful language that shuts down dialogue.

Clear, respectful language is the heart of assertiveness. It allows you to express needs without apology and without aggression. This requires two levels of skill. The first is upgrading everyday language, replacing vague or apologetic phrases with direct, specific ones. The second is using structured frameworks for difficult conversations, where stakes are high and clarity matters most.

Nonviolent Communication (Rosenberg, 1999) and the DESC script (Bower & Bower, 1976) are two such frameworks. Both offer a sequence that makes assertiveness easier to practise: describe the situation, express your feelings, state your needs, and make a clear request. These models help you move past instinctive reactions and into deliberate, constructive expression.

Language is more than words. It shapes relationships, influences perceptions, and changes outcomes. By upgrading your language and learning structured assertive communication, you not only become clearer, you also become more trustworthy. People respect those who can state their needs openly while still leaving room for others.

Steps

- Spot unhelpful language habits

Listen to how you usually frame requests or responses. Do you overuse apologies, hedges (“just,” “maybe”), or vague language (“whatever you think”)? Write down three common phrases.

Why: Awareness of habitual phrasing is the first step to change.

- Upgrade to assertive phrasing

Reframe each phrase to be clearer and more confident. Example:

-

- Instead of “Sorry, could you maybe send me that file?” → “Please send me the file by 3 p.m. so I can finish the report.”

- Instead of “I just think we should…” → “I recommend we take this approach because…”

Why: Specific, direct language signals confidence and prevents misunderstanding.

- Practise NVC (Observation–Feeling–Need–Request)

For more challenging situations, use the NVC sequence:

-

- Observation: What happened, factually.

- Feeling: How you feel.

- Need: What you require or value.

- Request: What specific action you are asking for.

Why: NVC connects assertiveness to needs and values, reducing defensiveness.

- Practise DESC (Describe–Express–Specify–Consequences)

For fast, business-like contexts, use DESC:

-

- Describe the behaviour.

- Express your feelings.

- Specify the change you want.

- State the consequences (positive outcomes of change).

Why: DESC is concise and effective for workplace problem-solving.

- Role-play delivery

Practise saying upgraded statements, NVC, and DESC out loud. Notice tone, pace, and body language. Adjust until your words match your intent.

Why: Assertiveness depends on congruence. Clear words with hesitant tone still sound unsure.

- Reflect after real use

After trying an assertive phrase in a real situation, note how it landed. Did the other person respond differently? Did you feel clearer?

Why: Reflection turns practice into growth.

Workplace examples Requesting clarity (Language Upgrade)

- Old habit: “Sorry, I’m just a bit confused about this.”

- Assertive upgrade: “I need more clarity on the next steps. Could you outline them now so I can move forward with confidence?”

Pushing back on extra work (NVC flow)

- “You’ve asked me to take on another project (Observation). I feel stretched and pressured (Feeling). I need time to complete the tasks I’ve already committed to (Need). I cannot commit to this one right now. Could we look at reassigning priorities or adjusting timelines? (Request)”

Giving feedback to a colleague (DESC flow)

- “Yesterday the report was submitted incomplete (Describe). I felt frustrated because I had to redo parts of it (Express). I need you to include all sections before submitting (Specify). That will help us avoid errors and prevent late nights fixing issues (Consequences).”

Personal examples

At home (Language Upgrade)

- Old habit: “I guess I’ll do the dishes since no one else is.”

- Assertive upgrade: “I feel tired from today and need some support. Could we share the dishes tonight so it doesn’t fall on one person?”

Friendship boundary (NVC flow)

- “In the past month, our plans have often changed last minute (Observation). I feel unsettled and disappointed when that happens (Feeling). I need more reliability in how I plan my time (Need). Could we agree to confirm plans at least a day in advance? (Request)”

Family disagreement (DESC flow)

- “When you raise your voice during discussions (Describe), I feel anxious and on edge (Express). I need us to keep a calmer tone if we want to continue the conversation (Specify). If we do that, we’ll resolve issues faster and with less tension between us (Consequences).”

Variations

- Language filter: For one week, write down phrases where you used “just,” “sorry,” or “maybe.” Rewrite them assertively in a journal.

- Pair practice: With a partner, role-play both NVC and DESC in the same scenario to see how each feels.

- Positive application: Use the frameworks for appreciation as well as boundaries: “When you included me in the project, I felt valued because I need collaboration. Could we keep that going?”

- Email upgrade: Practise rewriting emails to be more assertive, swapping vague requests for specific actions.

Why it matters: Assertiveness is often won or lost in the words we choose. Research shows that clear, direct communication reduces workplace stress and strengthens collaboration (Speed et al., 2018). NVC in particular has been linked to lower conflict and higher relationship satisfaction (Rosenberg, 1999). By upgrading habitual language and mastering structured frameworks, you equip yourself with tools to express clearly in any context — from low-stakes requests to high-stakes negotiations.

The deeper truth: Language is not neutral. It either hides or honours your needs. Each word you choose signals whether you believe your voice matters. Assertive communication skills are not about learning tricks; they are about aligning your words with your worth. When your language becomes clear, specific, and respectful, you stop hinting or apologising for your presence. You begin to speak as someone who knows that dignity does not require aggression and respect does not require silence.

Exercise 6: Saying no practice

Saying no is one of the hardest acts of assertiveness. Many of us are taught early on that “no” is selfish, rude, or disloyal. As a result, we hesitate. We cushion refusals with excuses, delay decisions until resentment grows, or say yes and pay the price later in exhaustion. The irony is that avoiding no rarely protects relationships, it undermines them. Unspoken resentment builds, trust weakens, and commitments made in guilt rarely carry the same energy as those chosen freely.

Assertiveness reframes no as an act of respect. Respect for yourself, for your limits, values, and priorities. And respect for others, giving them clarity rather than half-hearted consent. Roberts (2019) suggests that effective no begins with three essential moves: acknowledge, pause, respond. First, acknowledge the request to show you heard it. Then pause to interrupt your automatic yes. Finally, respond clearly and respectfully.

But how you respond matters. There is no one-size-fits-all no. Sometimes a direct refusal is needed. At other times empathy, alternatives, or conditions preserve goodwill. Mastering multiple strategies gives you the freedom to choose a response that is both authentic and effective. This exercise invites you to practise eight forms of no, so that saying no becomes not an act of defiance but an act of clarity.

Steps

- Acknowledge the request

Begin by recognising the other person’s request: “Thanks for asking” or “I see why this matters to you.”

Why: Respecting the asker helps your no land as thoughtful rather than dismissive.

- Pause before answering

Count silently to three or take one deep breath.

Why: Pausing interrupts automatic compliance and creates a space for choice.

- Check your reasons

Ask yourself: What am I protecting by saying no? Is it time, energy, values, or priorities?

Why: Linking no to a reason makes it clearer to you and easier to explain to others.

- Choose a response strategy

Select the type of no that best fits the situation: direct, reasoned, alternative, delayed, conditional, values-based, empathic, or referral.

Why: Having multiple strategies prevents rigidity and makes assertiveness adaptable.

- Deliver with congruence

Speak calmly, make eye contact, and keep your tone steady.

Why: Body language and tone carry as much weight as words in how your no is received.

- Reflect afterwards

Ask: How did the other person respond? How did I feel saying no? What worked, and what will I try differently?

Why: Reflection transforms a single no into a practice that builds skill over time.

Eight response strategies

- Direct NoClear and unambiguous. Best when the request is straightforward and explanation is unnecessary.

- Example: “No, I cannot take this on.”

- Why it works: Clarity prevents false hope and wasted time.

- Reasoned NoNo with a brief explanation.

- Example: “I cannot join this project because I am committed to completing the current deadlines.”

- Why it works: A short reason gives context without justifying excessively.

- Alternative NoDecline the original request but suggest another option.

- Example: “I cannot attend tonight, but I’d be glad to meet later this week.”

- Why it works: Keeps connection alive while protecting your boundary.

- Delayed NoAsk for time before deciding.

- Example: “Let me check my priorities and get back to you tomorrow.”

- Why it works: Reduces pressure and allows for a considered decision.

- Conditional NoDecline unless certain conditions are met.

- Example: “I cannot take this on unless resources are reallocated.”

- Why it works: Signals willingness but clarifies your limits.

- Values-Based NoAnchor your no in what matters most to you.

- Example: “I need to protect family time, so I cannot stay late tonight.”

- Why it works: Values frame no as integrity rather than rejection.

- Empathic NoShow understanding of their need while still declining.

- Example: “I know this project is urgent for you, and I need to say no this time.”

- Why it works: Balances compassion with clarity.

- Referral NoDecline but point them to another resource.

- Example: “I cannot help with this, but you might want to ask Alex, she has the expertise.”

- Why it works: Protects your time while still being constructive.

Workplace examples

- The late request: A manager asks you at 6 p.m. to take on more work.

- Acknowledge: “I see this is urgent.”

- Pause: one breath.

- Respond (Values-based no): “I need to protect my commitments outside of work, so I cannot stay late tonight.”

- The extra project: A colleague asks you to take on tasks outside your scope.

- Acknowledge: “Thanks for thinking of me.”

- Pause: count to three.

- Respond (Referral no): “I can’t help with this, but Jamie has capacity and could be a good fit.”

Personal examples

- The unwanted invitation: A friend asks you to an event you don’t want to attend.

- Acknowledge: “I appreciate the invite.”

- Pause: short breath.

- Respond (Direct no): “I won’t be coming this time.”

- The family favour: A relative asks you to take on childcare when you are already stretched.

- Acknowledge: “I know this matters to you.”

- Pause: silent count.

- Respond (Conditional no): “I cannot take this on unless we arrange extra support.”

Variations

- One-a-day practice: Practise one strategy per day across a week until all eight feel natural.

- Safe refusals: Begin with low-stakes situations, such as declining a shop offer, before moving to higher-stakes scenarios.

- Rehearsed templates: Write scripts for recurring requests (e.g., staying late, lending money). Keep them handy until they become natural.

- Partner practice: Role-play with a colleague or friend, alternating between asking and refusing.

Why it matters: Saying no is not a luxury but a necessity. Research shows that people who struggle to refuse requests are more vulnerable to stress, overload, and burnout (Hakanen & Bakker, 2017). The ability to decline respectfully protects your energy and builds trust. Practising multiple strategies ensures you can adapt to different contexts without guilt or aggression.

The deeper truth: No is not the end of the conversation. It is the beginning of honesty. Every no defines the space in which your real yes can flourish. By learning to say no with respect, you are not rejecting others, you are clarifying what you stand for. Assertiveness is not about pleasing everyone. It is about standing in your truth while leaving space for connection.

Exercise 7: Boundary mapping

Boundaries are not barriers but agreements about what is acceptable and what is not. Without them, you risk exhaustion, blurred roles, and quiet resentment. Many people only realise a boundary exists once it is violated, when they feel drained, frustrated, or ignored. At that point, assertion feels reactive rather than grounded.

Boundary mapping changes this. It is a proactive way of naming your limits in advance, role by role, and seeing them visually. By layering boundaries into non-negotiable, flexible, and negotiable strands, you turn vague feelings into clear commitments. This approach not only strengthens assertiveness but also makes it easier to communicate boundaries in conversations.

Steps

- Place yourself at the centre

Write “Me” in the middle of a page and circle it.

Why: Assertiveness begins with recognising that your time, energy, and values matter.

- Draw branches for roles

From the centre, draw outward branches for your main roles: Leader, Parent, Colleague, Partner, Friend, Volunteer.

Why: Boundaries often differ by role. Being clear across roles prevents role conflicts.

- Create three strands for each role

From each role branch, draw three secondary branches labelled:

-

- Non-negotiable (Red) – Core values and limits you will not compromise.

- Flexible (Yellow) – Limits that can shift occasionally with discussion.

- Negotiable (Green) – Context-specific, open to agreement.

Why: Sorting boundaries by firmness makes it easier to stand by the ones that matter most.

- Map activities and asks onto each strand

From each colour strand, draw further branches with specific boundaries:

-

- Leader → Non-negotiable: “I do not check emails after 7 p.m.”

- Leader → Flexible: “I can stay late once a week if agreed in advance.”

- Leader → Negotiable: “I am open to rotating chair roles for meetings.”

Why: Concrete examples translate abstract values into daily practices.

- Review the balance

Step back and ask:

-

- Do I have enough red boundaries protecting well-being?

- Am I too rigid in areas that could be flexible?

- Am I clear on which greens I am willing to let go of?

Why: Visual mapping highlights imbalances and blind spots.

- Practise voicing one boundary

Choose a red boundary and practise saying it aloud to someone in that role: “I will not accept personal criticism in meetings.”

Why: Assertiveness requires not just clarity but the courage to communicate.

- Update regularly

Redraw your map monthly. As your life shifts, so do your boundaries.

Why: Regular revision ensures boundaries keep pace with changing roles and pressures.

Workplace examples

- Leader Role → Non-negotiable: “I will not respond to work calls on weekends.”

- Leader Role → Flexible: “I can take one late call a week if planned in advance.”

- Leader Role → Negotiable: “I can join an ad-hoc project committee if capacity allows.”

- Colleague Role → Non-negotiable: “I will not tolerate being interrupted repeatedly.”

- Colleague Role → Flexible: “I can adjust workload occasionally if deadlines align.”

- Colleague Role → Negotiable: “I am willing to cover a shift once in a while.”

Personal examples

- Parent Role → Non-negotiable: “I will not argue with my partner in front of the children.”

- Parent Role → Flexible: “I can swap childcare duties if notified in advance.”

- Parent Role → Negotiable: “I am open to adjusting weekend schedules.”

- Friend Role → Non-negotiable: “I will not accept disrespectful jokes at my expense.”

- Friend Role → Flexible: “I can reschedule plans if needed with notice.”

- Friend Role → Negotiable: “I am open to trying new activities together.”

Variations

- Boundary audit: At the end of each day, note moments of resentment. At week’s end, place them into your map under red, yellow, or green.

- Role spotlight: Each month, focus on one role (e.g. leader, parent) and refine its boundary strands.

- Team version: Teams can create shared maps of collective boundaries (e.g. meeting etiquette, workload expectations).

- Garden metaphor: Replace branches with fences and gates: red = locked gate, yellow = gate that opens with agreement, green = open gate.

Why it matters: Boundaries act as the architecture of assertiveness. Without them, your voice falters because you are unclear on what you are standing for. Research shows that people with well-defined boundaries experience lower stress, clearer roles, and more sustainable relationships (Cloud & Townsend, 1992). Visual mapping makes boundaries explicit and memorable, transforming them from vague intentions into visible commitments.

The deeper truth: Boundaries are not barriers but bridges. They say: “This is how I can meet you without losing myself.” When you map your boundaries visually, you move from reacting under pressure to living with clarity. Your no gains weight, your yes gains freedom, and relationships gain trust. Assertiveness stops being a defensive skill and becomes a way of inhabiting life with integrity.

Exercise 8: The Contracting Conversation

Assertiveness reaches its fullest expression not in one-off refusals or requests, but in the way we negotiate ongoing agreements. Too often, commitments are entered vaguely: deadlines are assumed, responsibilities left undefined, and unspoken expectations simmer beneath the surface. The cost is frustration, unmet needs, and strained relationships.

Peter Block (2010) describes “contracting” as creating explicit agreements where both parties put their wants on the table. These wants are of two kinds: technical and relational.

- Technical wants are about the task, the work to be done, the resources required, the timeframes, the roles.

- Relational wants are about how people will work together, the tone, the style of interaction, the level of support or recognition.

Agreements falter when only one side is covered. Technical clarity without relational clarity feels cold and transactional. Relational goodwill without technical clarity feels warm but directionless. Assertiveness here means naming both kinds of wants openly, then negotiating trade-offs so the agreement supports the work and the relationship.

Steps

- List your wants privately

Before the conversation, divide your wants into:

-

- Critical needs (non-negotiable) vs Nice-to-haves (preferred but flexible).

- Technical wants (tasks, deadlines, resources) vs Relational wants (tone, style, trust, support).

Why: This prevents you from conceding essentials under pressure and ensures you do not overlook relational needs.

- Invite the other person to do the same

Ask them to note their own critical vs optional, technical vs relational wants.

Why: Mutual preparation sets the stage for transparency.

- Begin with acknowledgement

Frame the purpose: “I’d like us to be clear on both what needs doing and how we’ll work together, so we can avoid misunderstandings later.”

Why: This balances task and relationship from the outset.

- Share critical wants first

Start with your non-negotiables, both technical and relational.

Why: Unspoken deal-breakers are the main cause of later conflict.

- Explore nice-to-haves

Share your preferences and signal flexibility.

Why: Offering adaptability creates goodwill and keeps dialogue constructive.

- Listen and reflect back

Hear the other person’s wants fully, reflect them back, and check for understanding.

Why: Assertiveness requires respect; listening prevents defensiveness.

- Negotiate trade-offs

Look at where critical and optional wants overlap or clash. Explore compromises.

Why: Agreements are built not by avoiding differences but by managing them with honesty.

- Capture the agreement

Summarise both sides’ technical and relational agreements in writing.

Why: Clarity avoids drift and builds accountability.

Workplace example: Project contracting

- Your wants:

- Technical – Critical: Clear deadlines; access to project data.

- Relational – Critical: Respectful tone in meetings.

- Technical – Nice-to-have: Weekly written updates.

- Relational – Nice-to-have: Recognition of contributions in team meetings.

- Colleague’s wants:

- Technical – Critical: Flexibility on work hours.

- Relational – Critical: Trust not to be micromanaged.

- Technical – Nice-to-have: Ability to join client calls.

- Relational – Nice-to-have: Informal check-ins over coffee.

- Contract: “We agree to bi-weekly deadlines, with access to shared project data. Meetings will be conducted with respectful tone and without micromanagement. We will aim for weekly written updates and client call involvement where feasible. Recognition and informal check-ins will be included when time allows.”

Personal pxample: Household contracting

- Your wants:

- Technical – Critical: Equal contribution to household chores.

- Relational – Critical: Calm conversations when discussing tasks.

- Technical – Nice-to-have: Dinner together three nights a week.

- Relational – Nice-to-have: Expressions of appreciation when tasks are completed.

- Partner’s wants:

- Technical – Critical: Flexibility on chores during late work nights.

- Relational – Critical: Time alone after stressful days before tackling tasks.

- Technical – Nice-to-have: Shared grocery planning.

- Relational – Nice-to-have: Weekend walks together.

- Contract: “We commit to splitting chores equally, with flexibility during late nights. Conversations about tasks will remain calm. We will aim for three shared dinners per week and include regular appreciation of each other’s efforts. Grocery planning and weekend walks will be included when schedules allow.”

Variations

- Mini-contracts: Use this structure for even small agreements (e.g. meeting agendas: technical = finish in 45 minutes; relational = respectful listening).

- Team contracts: As a group, create shared agreements about both work practices (technical) and meeting culture (relational).

- Periodic reviews: Revisit contracts monthly or quarterly to see if criticals are still being met and if nice-to-haves are being honoured.

Why it matters: Conflict often arises not because people are unwilling but because expectations were never clear. By naming both technical and relational wants, contracting ensures that agreements are whole. Research in workplace psychology shows that explicit agreements increase trust, reduce role conflict, and strengthen collaboration (Block, 2010).

The deeper truth: Assertiveness matures into contracting. It is no longer just about saying no or yes in the moment, but about shaping ground where both voices can stand. When you declare your technical needs and your relational hopes, you bring your whole self to the table. The agreement that follows is not a trap but a framework for freedom, protecting dignity, enabling performance, and nurturing the relationship that carries the work.

Conclusion: Standing with dignity

Assertiveness is not a single technique or a personality trait you either have or lack. It is a daily practice of voicing your needs, beliefs, and feelings with clarity, while respecting the needs of others. The eight exercises in this article are not scripts to memorise but doorways into a stance of dignity. Each one offers a way to strengthen your voice, protect your boundaries, and engage in dialogue that sustains both self and relationship.

This matters because silence and aggression are equally costly. When you withhold your voice, you invite misunderstanding, resentment, and burnout. When you force your voice, you create distance, mistrust, and resistance. Assertiveness is the middle path: speaking with honesty while staying open to others. It is less about winning the conversation than about inhabiting it with integrity.

The practices outlined here are deliberately varied. Identifying your rights anchors confidence in self-worth. Listening assertively shows that openness can be as strong as declaration. The DESC method structures respectful confrontation. Saying no gives shape to your limits. Boundary mapping makes invisible lines visible and sustainable. Contracting conversations build agreements that are explicit and balanced. Together, these practices form a cycle: clarity of self, expression of voice, negotiation with others, and renewal of trust.

Assertiveness is not about being louder than others. It is about being clearer with yourself. It gives you the power to decide when and how to voice your truth, without apology and without aggression. Over time, this practice builds not only stronger relationships but also self-respect. You learn that your voice can be trusted, by you and by those around you.

Reflective questions

- Which of the eight practices feels most natural for you, and which one challenges you the most? What does that reveal about your growth edge?

- In what situations do you most often surrender your assertiveness, and what might change if you brought your voice into those moments?

- Which boundaries in your life need more clarity: time, respect, workload, or emotional space?

- How might your relationships change if you treated assertiveness not as a risk but as a gift to yourself and to others?

Assertiveness is not about becoming forceful. It is about becoming fully present. By practising it, you create the possibility of relationships grounded in trust and a life lived with balance, clarity, and dignity.

Do you have any tips or advice on practising assertiveness?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

References

Bar-On, R. (1997) BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) Technical Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Block, P. (2011) Flawless Consulting: A Guide to Getting Your Expertise Used. 3rd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Block, P. (1993) Stewardship: Choosing Service Over Self-Interest. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Cloud, H. and Townsend, J. (1992) Boundaries: When to Say Yes, How to Say No to Take Control of Your Life. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Edmondson, A. (1999) ‘Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp. 350–383.

Ellis, A. (1955) ‘New approaches to psychotherapy techniques’, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 11(3), pp. 207–260.

Gross, J.J. (1998) ‘The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review’, Review of General Psychology, 2(3), pp. 271–299.

Gross, J.J. (2002) ‘Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences’, Psychophysiology, 39(3), pp. 281–291.

Gross, J.J. and John, O.P. (2003) ‘Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), pp. 348–362.

King, L.A. and Emmons, R.A. (1990) ‘Conflict over emotional expression: Psychological and physical correlates’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), pp. 864–877.

Linehan, M.M. (1993) Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Rosenberg, M.B. (2003) Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. 2nd edn. Encinitas, CA: PuddleDancer Press.

Smith, T.W., Glazer, K., Ruiz, J.M. and Gallo, L.C. (2004) ‘Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: An interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health’, Journal of Personality, 72(6), pp. 1217–1270.

Srivastava, S., Tamir, M., McGonigal, K.M., John, O.P. and Gross, J.J. (2009) ‘The social costs of emotional suppression: A prospective study of the transition to college’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), pp. 883–897.

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E. (2006) The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons Canada.

Leave A Comment