We live in cultures that prize collaboration and connection. In workplaces, “team player” is often the highest compliment, while in families and communities, loyalty and togetherness are praised as the ultimate virtues. Yet beneath this emphasis on belonging lies a quieter challenge: the ability to act independently, to make decisions without leaning too heavily on approval, advice, or reassurance.

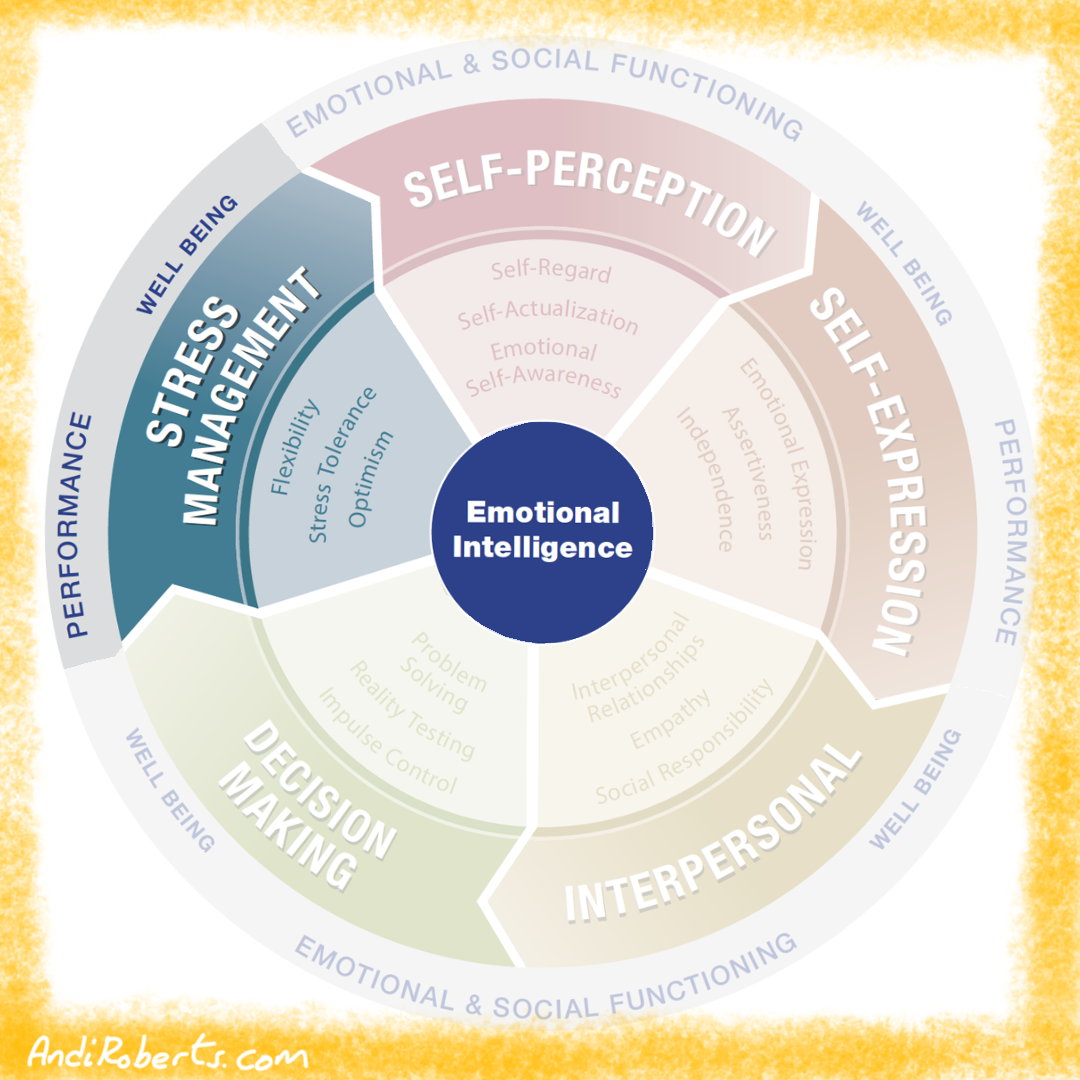

In the EQ-i model, independence is defined as the capacity to be self-directed and self-controlled in one’s thinking and actions, free from emotional dependency on others (Stein & Book, 2011). It is not about isolation or stubbornness. True independence sits alongside healthy interdependence. It means being able to think and decide for yourself, while still engaging openly with others.

The absence of independence carries real costs. When people are over-reliant on others, they can become hesitant, indecisive, or risk-averse. A leader who cannot act without consensus slows the team. An employee who constantly seeks reassurance drains their colleagues’ time and attention. In personal life, dependency can erode confidence and create imbalances in relationships.

By contrast, independence strengthens resilience and clarity. Research on self-efficacy shows that confidence grows most powerfully through direct mastery experiences, moments where you act on your own and discover you are capable (Bandura, 1997). Autonomy research also shows that people who feel free to make their own choices are more motivated, creative, and satisfied (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Independence, then, is not only a personal strength but a collective gift.

Why independence matters

If independence is the ability to act from self-direction rather than dependency, the natural question follows: why does it matter? Why emphasise standing on your own two feet in a world that so often prizes collaboration?

Resilience under pressure

When people are dependent on constant reassurance, stress multiplies under uncertainty. A leader who cannot act without consensus feels paralysed when decisions must be made quickly. A parent who relies on a partner for every choice feels lost when alone. Independent individuals, by contrast, can tolerate doubt, make decisions, and carry responsibility even when approval is absent. This ability to stand steady is what allows leaders, parents, and professionals to act with clarity in turbulent times.

Better decision-making

Independence strengthens clarity. Decisions are less clouded by the need to please, impress, or conform. A manager confident in their own analysis can weigh evidence and values directly, without waiting for everyone else to agree. A young professional who trusts her judgement avoids the paralysis that comes from over-consulting peers. Independence ensures that ownership and responsibility stay intact, which makes choices both faster and more authentic.

Stronger relationships and leadership

Ironically, independence does not weaken connection. It strengthens it. Relationships falter when people lean too heavily on one another for validation. Partners who cannot act without each other’s permission risk turning closeness into constraint. Leaders who cannot move without approval create climates of hesitancy. By contrast, independent people contribute with confidence, which makes interdependence richer and less burdened. They come to the table as whole participants, not as people waiting to be completed by others.

A foundation skill

In the EQ-i framework, independence underpins assertiveness, problem-solving, and authenticity (Stein & Book, 2011). Without it, collaboration becomes conformity, and empathy risks sliding into over-identification. With it, people can balance autonomy and connection, giving themselves and others the freedom to contribute fully.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Independence is the capacity to act autonomously, make decisions confidently, and manage tasks without undue reliance on others for emotional reassurance. In the EQ-i model, this composite captures how a leader balances self direction with healthy interdependence. The developmental question is not whether someone prefers to work independently, but how proportionately they rely on their own judgement while staying connected to others. When expressed in balance, independence supports clarity, initiative, and confident decision making. When underused it results in hesitation, dependence, and fear of acting alone. When overused it can become isolating, controlling, or dismissive of collaboration. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Needs frequent reassurance, direction, or protection from others. |

Acts autonomously and makes decisions with confidence. |

Believes they can handle everything alone. |

|

Uncertain of their own ideas or competence. |

Uses input appropriately without becoming dependent on it. |

Controls decisions and limits others’ involvement. |

|

Hesitates or struggles to decide without validation. |

Demonstrates self determination and follow through. |

Rejects guidance or feedback from others. |

|

Defers final decisions to others even when capable. |

Free from emotional dependence in daily tasks and planning. |

Avoids asking for help even when needed. |

|

Lacks confidence and fears making mistakes independently. |

Balances self reliance with collaboration and openness. |

Becomes isolated, distant, or dismissive of collective effort. |

Balancing factors that keep independence healthy and connected

Independence is most effective when supported by emotional skills that maintain clarity, groundedness, and relational balance. These balancing factors ensure independence does not collapse into dependence at the low end or isolation at the high end.

Problem solving: Problem solving strengthens independence by providing the analytical clarity needed to make decisions without excessive reliance on others. Leaders with strong problem solving can assess situations logically, work through uncertainty, and act decisively. This prevents low independence by reducing hesitation and fear of error. It also prevents overuse by ensuring decisions are not made unilaterally or impulsively but grounded in thoughtful evaluation.

Emotional self awareness: Emotional self awareness anchors independence in an accurate understanding of personal motives and emotional triggers. Leaders who understand their own feelings can recognise when they are seeking validation out of insecurity or rejecting support out of pride. This awareness prevents emotional dependence at the low end and emotional avoidance or self sufficiency at the high end. It allows independence to remain calm, confident, and appropriately supported.

Interpersonal relationships: Interpersonal relationships provide the relational balance that keeps independence connected rather than isolating. Strong relational skills help leaders maintain openness, trust, and mutual support even while operating autonomously. They are able to collaborate without losing their sense of self and to rely on others without becoming dependent. Healthy relationships protect against over independence by encouraging shared responsibility and preventing emotional or practical isolation.

Eight practices for building independence

Like all dimensions of emotional intelligence, independence is not built by theory or intention alone. It is cultivated through practice, in the ordinary choices where you decide whether to trust your own judgement or defer to others. The eight exercises in this article are designed as doorways into independence. Some are reflective, such as clarifying your values or auditing your dependencies. Others are practical, like independent work sprints or solo challenges. Still others are relational, showing how independence and interdependence strengthen one another.

Each exercise is structured in the same way:

-

Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

-

Steps guide you through the process.

-

Examples show it in real contexts.

-

Variations suggest ways to adapt.

-

Why it matters grounds the practice in research and lived insight.

The order matters less than where you begin. Over time, the practices reinforce one another. A values compass anchors your choices. A dependency audit highlights patterns. Independent sprints build stamina. Solo challenges consolidate confidence. Each one strengthens your ability to act without needing permission, reassurance, or validation.

These practices are not about disconnection. They are about presence. They allow you to trust your own voice, to carry responsibility with clarity, and to connect with others as a whole person rather than from neediness. Independence is not about standing apart. It is about standing steady, and from that steadiness, choosing how you want to engage.

Exercise 1: Independent Decision Journal

Independence is not about going it alone. In the EQ-i model it is the capacity to be self-directed and self-reliant, able to make choices without being overly dependent on reassurance or approval. It is a balance: open to input, but not defined by it.

The difficulty is that many of us have been trained to look outward before we act. Workplaces reward consultation and collaboration, but the line between seeking clarity and seeking comfort is thin. We ask colleagues to “just check this,” not because we doubt the facts, but because we doubt ourselves. We hold back opinions until others speak, assuming our worth depends on agreement. Over time, these habits weaken self-trust.

Psychological research shows that confidence grows not from telling ourselves we can act independently, but from experiencing it (Bandura, 1997). Each time we make a choice, own it, and see it through, we build what Albert Bandura called “self-efficacy”: the belief that we can succeed in the situations we face. The Independent Decision Journal is a way of tracking and amplifying these experiences.

By recording daily choices, noticing when we leaned too heavily on others, and highlighting moments of self-trust, we create a mirror of independence. Over time, this journal becomes evidence that you can think, choose, and act without constant reassurance.

Steps

1. Capture daily decisions

At the end of the day, write down 2–3 decisions you made. Include both large ones (choosing a strategy, saying yes to an opportunity) and smaller ones (how you framed an email, whether you spoke in a meeting).

Why: Independence grows in small choices as much as big ones. Recording them shows how often you already act without help.

2. Note sources of input

List whose opinion you consulted. Then ask: Was I seeking clarity or was I seeking comfort?

Why: Independence does not mean avoiding information, but it does mean noticing when reassurance, not knowledge, is driving you.

3. Rate reassurance needed

On a scale of 1–5, record how much reassurance you wanted before acting. Also note the emotion behind it, was it fear of failure, fear of rejection, or fear of conflict?

Why: Quantifying both intensity and emotion reveals patterns. Some find they seek reassurance most from authority figures, or only when conflict looms.

4. Highlight self-trust moments

Circle one decision where you acted without asking for reassurance. Note how it felt in the moment, and what the outcome was.

Why: Positive reinforcement builds a direct association between self-trust and capability rather than anxiety.

5. Reflect weekly

At the end of the week, review the log. Where did you rely too heavily on others? Where did you step forward on your own? Which emotions drove your reassurance-seeking?

Why: Reflection converts a list of events into a learning cycle. It points to specific growth edges for the next week.

Workplace examples

-

Manager: A manager hesitates to alter a meeting agenda without sign-off from their director. They choose to act independently, adjust the flow, and discover that the meeting is more productive. The journal captures the shift: independence did not damage trust, it strengthened it.

-

Team member: An analyst logs that they asked colleagues to review a report even though they were confident in it. On reflection, they see the request was about comfort, not clarity. Next week, they commit to presenting their work without extra checks.

Personal examples

-

Family: A parent chooses a weekend plan without polling extended relatives. While some initially resist, the clear choice reduces endless debate. The journal helps the parent see that independence can serve the group as well as the self.

-

Friendship: A person decides not to attend a social gathering, even though friends encourage them to go. Logging the decision, they reflect that honouring their energy was more valuable than keeping everyone else happy.

Variations

-

Colour coding: Use green for independent decisions, yellow for information-seeking, and red for reassurance-seeking. Over weeks, the balance of colours makes growth visible.

-

Independence ladder: Rank each decision from “needed heavy reassurance” at the bottom to “acted independently” at the top. Each week, aim to move one decision up the ladder.

-

Future prediction: Before acting, write down how much reassurance you think you’ll need. Afterward, record how much you actually needed. Seeing the gap between expectation and reality weakens dependency.

-

Team journal: Invite team members to keep their own independence logs. Share patterns in a meeting. This shifts culture from leader-dependence to collective ownership.

Why it matters: Without independence, decision-making slows, resilience weakens, and relationships tilt toward dependency. Journaling turns independence into a skill that can be observed and strengthened. Research shows that reflective writing improves clarity of thought, reduces stress, and builds self-regulation (Pennebaker, 1997). Self-efficacy grows through lived mastery experiences (Bandura, 1997). The Independent Decision Journal combines both: reflection and mastery.

The deeper truth: Independence is often misunderstood as isolation. In reality, it is what allows true connection. When you can make choices from your own centre, you enter relationships as a full self rather than half a self waiting for reassurance. Each logged decision becomes a stone in the foundation of self-trust. Over time, you no longer need to prove independence to others, you simply live it.

Exercise 2: Values compass

Independence is not only about making decisions alone. It is about making decisions that are anchored in something deeper than approval or habit. Many people hesitate to act without reassurance because they are unsure whether their choice is “right.” The antidote is to act from values. When decisions are aligned with what you stand for, you need less validation from others.

Psychologists note that values act as inner compasses, guiding action when external cues are unclear (Schwartz, 1992). Research on “self-concordant goals” shows that when choices align with personal values, people persist longer, cope better with stress, and feel more fulfilled (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). By contrast, when actions are driven by external approval, motivation is fragile and anxiety rises.

The Values Compass exercise helps you clarify what matters most to you and practise making choices through that lens. Instead of asking, “Will others approve?” you learn to ask, “Does this reflect who I am and what I stand for?” Over time, this question builds an inner anchor that steadies you in moments of doubt.

Steps

1. Clarify core values

Begin by writing down 5–7 values that feel most important to you. Examples include fairness, creativity, growth, family, honesty, or service. If you are unsure, reflect on moments when you felt proud, angry, or deeply satisfied, these emotions often signal values at stake.

Why: Values are the raw material of independence. Without clarity on what you stand for, you will drift toward others’ expectations.

2. Rank and define them

Choose your top three values and write one sentence about what each means to you. For example, “Fairness means giving everyone an equal chance to contribute.”

Why: Ranking prevents values from becoming vague ideals. Defining them in your own words makes them usable rather than abstract.

3. Test recent decisions

Look back at three decisions from the past week. For each, ask: Which value did this reflect? Did any decision contradict my values?

Why: Retrospective testing reveals whether you are acting from inner guidance or external approval. Patterns often emerge quickly.

4. Use values prospectively

Before making a new decision, pause and ask: Which value does this serve? How? If none apply, consider whether the decision aligns with your authentic direction.

Why: This step shifts values from reflection to active guidance, turning them into a compass you can use daily.

5. Reflect on the effect

After making a values-based decision, record how it felt. Did it bring more confidence, peace, or clarity, even if others disagreed?

Why: Reflection builds evidence that independence feels more secure when grounded in values than when tethered to approval.

Workplace examples

-

Leader in a meeting: A manager faces pressure to cut corners on quality to meet a deadline. Their value of integrity acts as a compass. They say, “I can’t support this path, quality is a non-negotiable.” The decision is unpopular, but the leader feels steadier knowing it reflects their core value.

-

Employee under pressure: An analyst feels pressured to agree with a group consensus. Their value of fairness prompts them to voice an alternative: “I think this option disadvantages the client.” Speaking from fairness gives courage, even without full agreement.

Personal examples

-

Family: A parent values presence with their children. When offered a new project that would demand long hours, they decline. The decision disappoints their manager but aligns with their compass of family first.

-

Friendship: Someone values honesty. When a friend asks for feedback on a sensitive topic, they respond truthfully but gently, even though it risks tension. The friendship deepens through trust.

Variations

-

Values cards: Write each value on a card. When facing a decision, spread the cards out and choose which one applies. This physical act makes the decision more concrete.

-

Team compass: Share values in a team setting and notice overlaps. When a decision is needed, ask: Which shared value guides us here? This builds collective independence from external pressures.

-

Daily compass check: At the end of each day, ask: Which decision today reflected my compass? Which did not? Over time, this strengthens alignment.

-

Conflict mapping: When you feel torn, write down which value supports each option. Seeing the values side by side often clarifies the way forward.

Why it matters: When you base choices on values, you act with more resilience. Even if outcomes are uncertain, you know why you acted. This reduces dependency on others’ approval. Research shows that values-based living increases persistence, well-being, and authentic motivation (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999; Schwartz, 1992). Independence grows not from rejecting others but from rooting yourself in what matters most.

The deeper truth: Independence is not about being unmoved by others. It is about being moved first and foremost by what you hold true. Values act as a compass in the fog of expectations, guiding decisions when consensus or approval are absent. Each time you choose in line with your compass, you strengthen self-trust. Over time, independence stops feeling like risk and starts feeling like alignment. You discover that you do not need permission to live by your values — you only need the courage to name them and act from them.

Exercise 3: Self-validation practice

Independence weakens when we outsource recognition. Many people work hard but feel uneasy until someone says, “Good job.” In teams and families, subtle approval-seeking often hides beneath the surface: repeating an opinion until it gets a nod, waiting for praise before feeling finished, or dismissing our own judgement until it is endorsed by someone else.

The problem is not that validation from others is bad. Encouragement and appreciation are vital in relationships. The problem arises when self-worth depends on external praise. Without it, people feel empty or unsure, and with it, they feel temporarily secure but quickly dependent again. Over time, this cycle erodes independence.

Research on self-affirmation and self-compassion shows that recognising your own strengths builds resilience and reduces reliance on external approval (Sherman & Cohen, 2006; Neff, 2003). By learning to validate ourselves directly, we strengthen the inner voice that says, “I am enough, even if nobody else says it.”

The Self-Validation Practice helps you shift from needing applause to recognising your own worth. It trains the habit of noticing contributions, affirming them, and building a steady inner foundation.

Steps

1. Daily reflection

At the end of each day, write down three things you did well. These can be small (sending a thoughtful email) or large (handling a conflict calmly).

Why: Small wins accumulate. Independence grows when you consistently notice your own contributions.

2. Use your own language

Phrase each validation in words that feel authentic. Instead of “I did well,” try “I showed patience when I wanted to snap,” or “I stayed aligned with my values.”

Why: Specific, authentic language strengthens self-recognition more than vague praise.

3. Anchor in effort and values

Focus on effort, courage, or alignment with values, not just outcomes. For example: “I spoke my opinion even though it was uncomfortable.”

Why: Effort and alignment are under your control. Basing validation on them makes it steadier than results alone.

4. Notice the discomfort

If affirming yourself feels awkward, write that down too. For example: “This feels forced.”

Why: Independence requires tolerating the discomfort of breaking approval habits. Naming it reduces its power.

5. Review weekly

At the end of the week, read through your validations. Circle any themes that repeat, such as courage, honesty, or persistence.

Why: Seeing patterns builds confidence that you are not occasionally capable but consistently so.

Workplace examples

-

Team member: An employee notices they presented confidently in a meeting even though they felt nervous. Instead of waiting for a colleague’s comment, they log: “I held my ground and spoke clearly despite pressure.” The record becomes an anchor of self-recognition.

-

Leader: A manager affirms themselves for protecting their team’s focus by saying no to extra work. They record: “I acted in line with my value of sustainability, even though it risked disapproval.” Over time, the practice reinforces decisions rooted in inner guidance rather than external validation.

Personal examples

-

Friendship: After hosting a dinner, someone feels uneasy because no one complimented the food. In their journal they write: “I created a warm atmosphere, and people laughed and connected.” The self-validation replaces dependence on praise with confidence in contribution.

-

Parenting: A parent reflects: “I stayed calm during my child’s tantrum, even though it was hard.” Logging this builds recognition of resilience without waiting for thanks, which rarely comes in parenting.

Variations

-

Voice recording: Instead of writing, record your validations as short audio notes. Hearing your own voice affirm you reinforces the message.

-

Mirror practice: Speak one validation aloud each morning in front of a mirror. It may feel awkward, but repetition builds confidence.

-

Theme journaling: Dedicate a week to affirming one theme, such as courage or patience. This deepens recognition of a specific quality.

-

Team version: Invite team members to write self-validations at the end of meetings. This shifts culture from dependence on leader praise to shared self-recognition.

Why it matters: Self-validation builds independence because it shifts the source of worth from others to self. Research on self-affirmation shows that reflecting on strengths buffers against stress and reduces defensive reactions (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). Self-compassion studies show that treating oneself kindly after setbacks supports resilience (Neff, 2003). By practising daily self-validation, you internalise recognition and reduce the hunger for constant reassurance.

The deeper truth: Independence does not mean never needing affirmation. It means not being defined by its presence or absence. Each time you validate yourself, you strengthen an inner foundation that others cannot give or take away. Over time, independence stops being the absence of approval and becomes the presence of self-trust. You move from waiting for applause to carrying your own quiet conviction.

Exercise 4: Solitude practice

Independence does not grow only in moments of bold decision-making. It also matures in quiet spaces, when you are alone with your own thoughts, feelings, and values. Yet solitude is something many people avoid. In a world where constant communication is rewarded, being alone can feel unsettling, even threatening. Silence leaves us face to face with our doubts. Without the noise of others’ voices, we may fear we are empty or insignificant.

Cultural pressures amplify this discomfort. Workplaces prize teamwork and responsiveness, making time alone seem unproductive. Social media celebrates connection, turning solitude into a kind of social failure. Even in families, time to oneself is often judged as selfish. The result is that many people go through life over-dependent on external validation, rarely testing whether their inner resources are enough.

Psychologists have long recognised the role of solitude in shaping selfhood. Rollo May (1953) argued that solitude is essential for authentic identity, because it separates what is truly ours from what is borrowed. More recent research shows that solitude, when chosen intentionally, increases creativity, emotional regulation, and clarity of values (Nguyen et al., 2018). Studies of nature-based solitude demonstrate that even short periods of quiet reflection in natural settings restore attention and reduce stress (Kaplan, 1995). Far from being empty, solitude is fertile ground where independence takes root.

The Solitude Practice is about deliberately choosing time alone with yourself. It is not withdrawal or isolation, but presence. It trains you to tolerate silence, listen inwardly, and rediscover that your own company is enough.

Steps

1. Choose a rhythm

Decide when solitude will happen. Start small, 15 minutes a day or one hour a week, and gradually lengthen. Protect this time in your calendar.

Why: Independence grows through rhythm, not rare retreats. Regular solitude builds familiarity until silence feels safe rather than strange.

2. Set clear conditions

Switch off devices, close distractions, and find a place where you will not be interrupted. This could be a quiet room, a park bench, or a daily walk.

Why: Independence is tested when external voices are absent. Creating conditions of quiet ensures that you are actually alone with yourself rather than half-connected.

3. Begin with grounding

Take a few minutes to breathe slowly, notice your body, or observe your surroundings. Allow your mind to settle before diving into reflection.

Why: Grounding counters the restless urge to fill silence with activity. It creates space for deeper awareness to emerge.

4. Engage in reflective activity

Choose a focus that suits you:

-

Journaling about your current state of mind.

-

Silent sitting with attention on thoughts and feelings.

-

Walking slowly, noticing sensations and reflections as they arise.

-

Ask guiding questions: What am I feeling right now? What value is calling for attention? What am I avoiding?

-

Why: Structure helps prevent solitude from collapsing into distraction or rumination. Reflective activities give shape to the silence.

5. Notice the discomfort

Write down what arises when you are alone. Do you feel restless, lonely, or anxious? Do you reach for your phone or imagine what others might say?

Why: Independence means tolerating the unease of being self-contained. Naming discomfort reduces its hidden power.

6. Reflect on insights

At the end, record what you discovered. Did solitude bring calm, clarity, or creativity? Did you reconnect with values or needs you had overlooked?

Why: Reflection makes solitude productive. It turns silence into lessons that carry back into daily life.

Workplace examples

-

Leader: A senior manager schedules a “solitude block” every Monday morning ,one hour with no email, meetings, or interruptions. At first, they feel guilty for being unavailable. But over time, they use this block to reflect on priorities, reconnect with values, and plan decisions. Colleagues notice that their communication becomes clearer and less reactive.

-

Employee: A young professional takes a daily 20-minute walk outside without their phone. At first, the silence feels awkward, but within weeks they find themselves brainstorming ideas and reflecting on goals. They discover that solitude helps them bring original perspectives to meetings.

Personal examples

-

Parent: A parent in a busy household feels constantly drained. They claim 30 minutes each evening to sit alone in a quiet room and journal. At first, family members resist, but the parent explains that solitude restores their energy to engage fully with others. Over time, the family comes to respect this practice.

-

Student: A student overwhelmed by peer pressure experiments with solitary study in the library. Alone, they realise their preferred learning style is different from their friends’. Solitude reveals independence not just in choices but in identity.

Variations

-

Micro-solitude: Insert 2–5 minute pauses into the day, stepping outside between meetings, closing your eyes before a call. Small doses build tolerance.

-

Creative solitude: Use solitude for writing, painting, or problem-solving. Engaging in creative flow strengthens the belief that you can generate value without external input.

-

Extended solitude: Once or twice a year, plan a half-day or weekend retreat. Extended time alone magnifies the benefits of shorter practice.

-

Nature-based solitude: Practise solitude outdoors. Research shows that time in nature amplifies restoration, increasing calm and perspective (Kaplan, 1995).

-

Leadership solitude: In team settings, leaders can model solitude by visibly blocking reflection time, showing that independence is not isolation but stewardship of clarity.

Why it matters: Without solitude, we risk becoming echoes of other people’s priorities. Dependence grows when we never test our capacity to think and feel on our own. Research shows that reflective solitude enhances creativity, strengthens emotional regulation, and clarifies identity (Nguyen et al., 2018). It interrupts the cycle of constant approval-seeking by proving that you can be with yourself, and that your own company is a sufficient source of clarity.

The deeper truth: Solitude is not absence but presence, the presence of self without distraction. Independence begins when you can listen inwardly as attentively as you listen outwardly. Each deliberate period of solitude teaches you that your thoughts have weight, your values have direction, and your feelings deserve attention. Over time, solitude becomes less a withdrawal from life and more a return to yourself. From that return, independence flows, not as isolation, but as the quiet confidence to stand on your own, and then re-enter relationships as a whole and grounded self.

Exercise 5: Independent work sprint

Independence is tested not only in the big decisions of life but also in the daily rhythm of work. Many people unconsciously rely on others’ direction or reassurance to move forward. They check emails before starting, ask for quick approval on small tasks, or delay until a colleague confirms they are on the right track. These habits are rarely malicious. They arise from a workplace culture that prizes collaboration and accountability. Yet over time they create dependency. The signal becomes: “I cannot move until someone else validates me.”

True independence in work means trusting your own judgement enough to begin, persist, and complete a task without leaning excessively on external guidance. This does not mean avoiding input forever, but it does mean practising periods of self-reliance where you are fully responsible for choices and actions.

Research on self-regulation shows that concentrated blocks of focused work, without interruption, increase both productivity and self-confidence (Baumeister & Vohs, 2007). Independent work sprints build this capacity. They are short, deliberate periods where you commit to working without seeking reassurance, feedback, or distraction. Over time, these sprints train you to anchor in your own direction rather than constantly checking outside.

Steps

1. Define the sprint

Choose a specific task and set a fixed time period, such as 90 minutes. Commit to completing the task without seeking feedback, checking emails, or asking for validation until the sprint ends.

Why: Clear boundaries prevent drift. Independence strengthens when you know exactly what you are holding yourself accountable for.

2. Prepare your environment

Clear away distractions. Close email, silence notifications, and gather everything you need before you begin.

Why: Removing opportunities for reassurance-seeking forces you to rely on your own focus and resources.

3. Set an intention

Before starting, write one sentence: “In this sprint, I will complete X by relying on my own judgement.” Read it aloud.

Why: Stating intention makes independence explicit. You are reminding yourself that you are capable of directing your own work.

4. Work without interruption

Engage fully in the task for the set time. If you feel the urge to check in with someone, note it on paper and continue.

Why: Recording the urge allows awareness without indulgence. You see how often reassurance calls you, but you are no longer controlled by it.

5. Review outcomes

At the end, reflect. What did you complete? Where did you feel strong? Where did you feel tempted to seek input?

Why: Reviewing outcomes provides evidence of competence. You realise that independence is not reckless but effective.

6. Scale up

Gradually increase the length or complexity of sprints. Move from 30 minutes to two hours, or from routine tasks to strategic projects.

Why: Scaling ensures that independence is transferable, from small wins to larger challenges.

Workplace examples

-

Analyst: An analyst normally asks colleagues to review each section of a report before proceeding. They set a two-hour sprint to draft the entire report independently. At first, they feel anxious, but by the end they have produced more in two hours than in a day of stop-start checks. When they later share the report, colleagues confirm its quality. The sprint becomes a proof point of competence.

-

Leader: A department head blocks out a three-hour sprint to design next quarter’s strategy without input. In the past, they circulated endless drafts for feedback. Working independently, they produce a coherent plan that they later refine with colleagues. The process shows that collaboration is more effective when independence comes first.

Personal examples

-

Student: A student commits to solving exam questions for 90 minutes without asking friends for help. They note urges to message for answers but resist. By the end, they discover gaps in knowledge but also greater confidence in what they already understand.

-

Freelancer: A freelancer spends a morning creating designs without browsing online for inspiration. At first, the work feels less secure, but the end result feels more original. They learn that their own resources are deeper than they believed.

Variations

-

Micro-sprints: Start with short bursts of 15–30 minutes if longer blocks feel intimidating. Build confidence gradually.

-

Reflection notes: Record every moment you feel the pull to seek reassurance. At the end, review the list to see patterns in when and why dependency arises.

-

Team sprint: Invite an entire team to try independent sprints simultaneously. Later, share reflections about how it felt to act without external input.

-

Creative sprint: Use sprints for creative work such as writing, coding, or design. Independence in creative tasks strengthens trust in your own originality.

Why it matters: Independent work sprints build the muscle of self-direction. Research on ego depletion and self-regulation shows that resisting distractions and tolerating uncertainty increases resilience and confidence (Baumeister & Vohs, 2007). By practising independence in bounded, low-risk periods, you develop the habit of trusting your own competence. Over time, this reduces dependence on reassurance and accelerates decision-making.

The deeper truth: Independence is not an abstract trait. It is learned through lived experiences where you prove to yourself that you can act without constant approval. Each sprint is a rehearsal of autonomy, a reminder that your judgement is capable and sufficient. Over time, independent sprints accumulate into evidence that you are not defined by others’ feedback but guided by your own clarity. Independence becomes less about rejecting connection and more about carrying your own weight within it.

Exercise 6: Decision-with-feedback distinction

Independence is not the rejection of others’ perspectives. It is the ability to distinguish between input that adds clarity and reassurance that masks insecurity. Many people blur this line. They believe they are seeking feedback when, in truth, they are asking for permission. They circulate drafts again and again, hoping to hear, “This is good.” They present an idea tentatively, waiting for a nod before owning it. The cycle appears collaborative but is often dependency in disguise.

The key skill is learning to separate information-seeking from validation-seeking. Information provides new facts or perspectives that help refine a decision. Validation provides comfort but rarely new insight. Both have value, but only one strengthens independence. Without this distinction, leaders become paralysed by endless consultation, employees hesitate to act without constant approval, and personal confidence erodes.

Research on decision-making shows that clarity improves when individuals anchor choices internally first and then use external perspectives to test and refine, not to replace, their judgement (Janis & Mann, 1977). Self-determination theory also suggests that autonomy grows when people experience themselves as the origin of action, rather than passive responders to external signals (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The Decision-with-Feedback Distinction puts these insights into practice. It trains you to commit to a decision internally before consulting others, ensuring that feedback serves learning rather than dependency.

Steps

1. Name the decision

When facing a choice, write down clearly what decision needs to be made. Be specific: “Approve the draft report,” “Choose between two job offers,” or “Select the agenda for a meeting.”

Why: Independence begins with clarity. Without naming the decision, it is easy to drift into endless dialogue without ownership.

2. Make a private commitment

Before speaking to anyone, write down what you would decide if no one else were involved. Note both the choice and your reasons.

Why: Private commitment anchors the decision in your own judgement. You begin from self-direction rather than external cues.

3. Identify the purpose of feedback

Ask yourself: “What am I hoping to gain from others?” If the answer is “reassurance,” acknowledge it and return to your own reasoning. If the answer is “information I do not yet have,” proceed to ask.

Why: Naming purpose distinguishes clarity-seeking from comfort-seeking. It prevents disguised approval-seeking from weakening independence.

4. Seek targeted input

If you need information, ask specific questions: “What risks do you see with option A?” or “What data might I be missing?” Avoid open-ended prompts like, “Do you think this is a good idea?”

Why: Targeted questions gather insight without surrendering responsibility. Independence remains intact while still valuing others’ expertise.

5. Compare and refine

After hearing input, return to your private commitment. Does new information alter your decision? If so, adjust. If not, confirm your choice and proceed.

Why: Feedback becomes additive rather than directive. The decision remains yours, even if refined by others’ perspectives.

6. Reflect afterward

After acting, ask: “Did I seek information or reassurance? Did feedback change my decision or simply comfort me?” Record your answer in a journal.

Why: Reflection reinforces awareness of patterns, helping you reduce dependency over time.

Workplace examples

-

Team leader: A project manager needs to decide whether to extend a deadline. Privately, she commits to a two-week extension based on resource constraints. She then asks her team for information: “What client impacts might we face if we delay?” Feedback confirms her reasoning, and she announces the extension with confidence. Because she distinguished between input and approval, she acted decisively without endless waiting.

-

Analyst: An analyst must choose between two reporting formats. They privately decide on option B but ask colleagues: “Are there compliance requirements I might be missing?” Input reveals a small legal detail, but it does not change the overall decision. The analyst proceeds with option B, strengthened by targeted feedback rather than dependent on consensus.

Personal examples

-

Student: A student considers two universities. Privately, she chooses the one that aligns with her values of exploration and diversity. She then asks alumni from both schools for information about teaching styles. Their insights confirm her sense of fit. The decision remains hers, rooted in values, sharpened by information.

-

Friendship: A person plans a holiday destination. Privately, he commits to a location he has always wanted to visit. He then asks friends: “What travel logistics should I be aware of?” The responses help him prepare, but the decision does not shift. He realises he was seeking information, not permission.

Variations

-

Decision log: Keep a notebook of major decisions, noting your private commitment, what feedback you sought, and whether it was for clarity or comfort. Over time, the log reveals your balance between independence and dependency.

-

Feedback fast: For a week, commit to making one decision each day without asking for feedback. Afterward, reflect on what you learned about your own capacity.

-

Team version: In group meetings, explicitly separate two steps: “Here is the decision I propose” and “Here is the input I need to refine it.” This models independence for the whole team.

-

Mentor check: When consulting a mentor, say explicitly: “I am not asking for approval. I am asking what risks or blind spots I might be missing.” This makes the purpose of feedback clear.

Why it matters: Without this distinction, feedback becomes a mask for dependency. People confuse approval with learning and never develop confidence in their own direction. Research shows that decision-making is stronger when individuals commit internally before consulting others (Janis & Mann, 1977). Autonomy theory emphasises that feeling like the origin of action is critical for motivation and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 1985). By practising this distinction, you transform feedback from a crutch into a catalyst.

The deeper truth: Independence does not mean never asking for advice. It means asking for the right reasons. When you can commit privately before consulting others, you stop handing away ownership of your choices. You discover that feedback is not permission but perspective. Over time, this shift redefines relationships. Others stop being judges of your adequacy and become partners in your growth. Independence then becomes not the absence of others’ voices but the ability to hear them without losing your own.

Exercise 7: Support vs dependency audit

Independence does not mean rejecting support. It means learning to distinguish between support that strengthens autonomy and dependency that weakens it. Many people blur this line. They lean on colleagues, friends, or family for comfort in ways that reduce their own initiative. What begins as healthy interdependence can quietly shift into patterns where responsibility is outsourced and confidence erodes.

This confusion is common because support and dependency look similar on the surface. Both involve asking others for help. The difference lies in the effect. Support provides resources, insight, or encouragement that you use to grow your own capacity. Dependency replaces your effort with someone else’s, leaving you weaker. For example, asking a mentor for advice on how to think through a problem is support. Asking them to make the decision for you is dependency.

Research on learned helplessness shows that when people repeatedly hand responsibility to others, they lose confidence in their own ability to act (Seligman, 1975). By contrast, studies on social support show that when assistance is empowering, it strengthens resilience and independence (Cohen & Wills, 1985). The Support vs Dependency Audit is a structured way of reviewing your relationships and habits, to ensure that your reliance on others remains healthy.

Steps

1. Map your support network

Write down the people you most often turn to when you face challenges. Include colleagues, managers, mentors, friends, and family.

Why: Independence begins with awareness. Many patterns of dependency are invisible until you see them laid out clearly.

2. Record the asks

Next to each name, write down the kinds of requests you make. Be as specific as possible. Do you ask them for:

-

Information: facts, resources, or knowledge you lack.

-

Feedback: opinions or assessments of your work.

-

Emotional comfort: reassurance, encouragement, or sympathy.

-

Decisions: permission or direction on what action to take.

-

Practical help: hands-on assistance with tasks or logistics.

-

Validation: signs of approval that boost confidence but do not change the substance of your choice.

For each person, note two or three concrete examples. For instance: “I ask my manager to recheck emails before I send them,” “I ask my partner if my decision sounds right,” or “I call my friend whenever I feel unsure about social plans.”

Why: Different types of requests reveal whether you are using support to grow or to avoid responsibility. Asking for information adds knowledge you can use. Asking for decisions shifts responsibility away from you. Recording actual examples surfaces patterns that are otherwise hidden and shows where the line between support and dependency is being crossed.

3. Identify the effect

For each person, note how you feel after receiving help. Do you feel stronger, clearer, and more capable? Or do you feel relieved but less responsible?

Why: The outcome distinguishes support from dependency. Empowerment increases independence; relief without responsibility increases reliance.

4. Classify the relationship

Label each as “supportive” or “dependent.” Some may fall in the middle, and that is natural.

Why: Labelling forces you to confront patterns. It shows where support is healthy and where it has slipped into dependency.

5. Choose one shift

Select one dependent relationship and design a small shift. For example: instead of asking a colleague to fix a spreadsheet, ask them to explain the formula so you can learn it yourself.

Why: Small shifts build independence gradually. You reduce dependency by converting it into skill-building support.

6. Reflect on balance

At the end of the week, ask: Did I lean too heavily on anyone? Did I avoid support altogether? Where did support strengthen me and where did it weaken me?

Why: Reflection ensures the audit becomes a cycle of learning, not just a one-time review.

Workplace examples

-

Employee and manager: An employee asks their manager daily to check small emails before sending. In the audit, they realise this is dependency. They shift by drafting the emails independently and asking only for feedback on tone at the end of the week. Confidence grows, and the manager appreciates the initiative.

-

Leader and mentor: A leader always asks their mentor what decision to make. After auditing, they reframe the request: “Here is the decision I am leaning toward. What risks should I consider?” The mentor’s role shifts from rescuer to challenger, and the leader grows more decisive.

Personal examples

-

Friendship: A person always calls a close friend for reassurance before making social plans. In the audit, they notice they never decide alone. They shift by making one plan independently, then sharing it afterward. They feel a surge of confidence in their own judgement.

-

Family: A young adult realises they still rely on their parents to manage finances. Instead of asking them to pay bills, they ask them to teach the process. Support shifts from dependency to learning, increasing independence.

Variations

-

Daily reflection: At the end of each day, ask: “Did I seek support today? Was it empowering or disempowering?” This builds moment-to-moment awareness.

-

Team audit: Teams can map where they rely too heavily on one member. Shifting tasks around reduces dependency and distributes competence.

-

Boundary experiment: For one week, commit to not asking for help on a recurring issue. At the end, evaluate how well you managed.

-

Mentorship version: Mentors can explicitly tell mentees: “I will not decide for you, but I will help you see options.” This reinforces the line between support and dependency.

Why it matters: Dependency drains independence. It erodes confidence, reduces initiative, and creates imbalances in relationships. Support, by contrast, builds resilience and extends capacity. Research confirms that empowering support strengthens independence and wellbeing (Cohen & Wills, 1985), while dependency patterns resemble learned helplessness, reducing confidence and autonomy (Seligman, 1975). The audit is a simple way to monitor the balance. It ensures that support remains a foundation for growth, not a substitute for responsibility.

The deeper truth: Independence is not the absence of help. It is the wisdom to know which help strengthens you and which weakens you. When you distinguish between support and dependency, relationships shift. Others stop carrying your responsibilities for you and begin equipping you to carry them yourself. Over time, you learn that the most empowering support does not reduce independence but magnifies it. True autonomy is not built in isolation but in relationships where help is offered as fuel, not as a crutch.

Exercise 8: Solo challenge

Independence matures when you step into situations where there is no safety net. Many people believe they are independent, yet in practice they rarely act without consulting, checking, or sharing the load. This does not mean they are incapable, only that they have not tested their capacity alone. Growth often requires deliberately creating those tests.

The Solo Challenge is a structured practice of choosing an activity or decision that you would normally approach with support, and doing it entirely on your own. It might be a work project, a presentation, a personal task, or a practical responsibility. What matters is that you resist the pull to outsource direction, comfort, or validation. Instead, you design the process, make the decisions, carry the risk, and then reflect on the outcome.

It is important to distinguish this practice from the Independent Work Sprint. Sprints are short, bounded blocks of focus, where you practise working without reassurance in your daily routine. They are like training intervals, repeated small doses that strengthen your independence muscle. The Solo Challenge is different. It is a larger, higher-stakes activity carried from beginning to end without external support. Think of it as the race day that puts your training to the test. Both are essential: sprints build stamina, while challenges consolidate confidence through lived evidence.

Psychologist Albert Bandura’s research on self-efficacy shows that confidence develops not from theory but from mastery experiences, direct encounters where you prove to yourself that you can handle a challenge (Bandura, 1997). Similarly, resilience research shows that facing manageable tests strengthens capacity for larger ones (Masten, 2001). The Solo Challenge provides these mastery experiences in daily life, building independence through lived evidence.

Steps

1. Choose a challenge

Identify one task or decision you usually share, delegate, or check with others. Examples: planning a meeting, handling a client call, or organising a household budget. Choose something significant but not overwhelming.

Why: Independence grows most when you stretch yourself without breaking. A manageable challenge creates a safe arena to practise autonomy.

2. Set clear boundaries

Before you begin, define the limits of the challenge. Write down what kinds of help are off the table. For example:

-

No asking for reassurance (“Does this look okay?”).

-

No seeking advice on direction (“What would you do?”).

-

No outsourcing decisions (“Can you decide this for me?”).

You may still use factual resources (manuals, data, policies), but not human stand-ins for your own judgement. Some people even choose to tell others in advance: “I am practising doing this independently, so I will not be asking for advice on it this time.”

Why: Boundaries prevent dependency from creeping in unnoticed. When you draw the line clearly, you train yourself to recognise the difference between support that informs and support that replaces your responsibility.

3. Prepare thoroughly

Preparation is not a way of hedging independence. It is what makes it possible. Before acting, take time to:

-

Gather resources: Collect the tools, data, or materials you will need.

-

Map the process: Write down the sequence of steps you will follow.

-

Anticipate obstacles: List the doubts, risks, or likely challenges. Next to each, outline how you might respond.

-

Rehearse mentally: Imagine yourself handling difficult points , a tough client question, a budgeting error, a moment of uncertainty.

-

Ground emotionally: Use a centring practice such as deep breathing, journaling, or affirmations to anchor confidence.

Why: Preparation strengthens self-trust. It reduces the chance of panic and ensures you are not caught off guard. Independence is not recklessness; it is the product of careful readiness married with self-direction.

4. Act independently

Carry out the task from start to finish on your own. Resist the urge to ask: “Does this look right?” or “What do you think?”

Why: Action without validation is the heart of the exercise. It converts independence from an idea into a lived practice.

5. Review the outcome

Afterward, evaluate the result. What worked well? What could you improve? Did independence increase your efficiency, creativity, or clarity?

Why: Reviewing outcomes provides evidence. Even imperfect results strengthen the belief that you are capable of self-direction.

6. Scale and repeat

Gradually increase the size of the challenge. Move from one meeting to an entire project, from one budget to longer-term planning, from a personal errand to a significant life choice.

Why: Repetition turns independence into habit. Scaling ensures that confidence extends across domains of life.

Workplace examples

-

Employee: A junior employee always checks drafts with colleagues before submitting them. As a Solo Challenge, she completes and submits a full report independently. When her manager praises the quality, she realises she has been underestimating her own competence.

-

Leader: A team leader usually consults widely before setting meeting agendas. For a Solo Challenge, he designs the agenda alone and communicates it with confidence. The meeting runs smoothly, and he recognises that his judgement can carry without external reassurance.

Personal examples

-

Parent: A parent often relies on their partner to make decisions about household spending. For a Solo Challenge, they take responsibility for planning and paying bills one month. At first, they feel anxious, but by the end they experience pride in handling the process independently.

-

Student: A student always asks friends to review assignments. For a Solo Challenge, she submits one without peer checks. She receives a strong grade, proving to herself that her own preparation is enough.

Variations

-

Advice fast: For a week, commit to making one decision each day without seeking advice. Afterwards, reflect on what you learned about your own capacity.

-

Silent preparation: Choose a project and prepare all plans without discussing them with others. Only after you have completed the draft do you share it, as a finished product.

-

Personal life version: Apply the challenge outside work. Plan a holiday, organise a move, or resolve a practical problem entirely by yourself.

-

Creative solo: For artists or creators, commit to producing one full piece without showing drafts for feedback. This strengthens originality and trust in your own voice.

Why it matters: Independence cannot be built in theory. It must be lived. Research shows that mastery experiences are the strongest source of self-efficacy, the belief in one’s ability to succeed (Bandura, 1997). Each Solo Challenge becomes such an experience. It proves to you, not just to others, that you can direct and complete tasks without leaning on reassurance. This confidence transfers across domains, reducing over-dependence and increasing resilience.

The deeper truth: Independence is not about rejecting connection but about discovering that you are enough. Each Solo Challenge is a rehearsal of trust in yourself. You stop outsourcing responsibility for your choices and begin carrying them with clarity. Over time, independence becomes less about occasional bravery and more about a way of living: choosing, acting, and reflecting without waiting for permission. From that foundation, interdependence with others becomes stronger, because you show up not as someone needing approval, but as someone already grounded in their own voice.

Conclusion: Standing steady in your own voice

Independence is not about walking alone. It is about learning to stand steady enough in your own voice that connection with others becomes freer and more genuine. The eight practices in this article are not endpoints but starting points. Each one offers a different way to notice where dependency has crept in, and to practise trusting your own capacity in its place.

What matters most is not perfection but rhythm. Independence grows in small choices, repeated daily. Saying “I will decide this myself.” Choosing to act without waiting for reassurance. Owning an outcome, even when it brings mistakes as well as progress. These are the moments where independence takes root, not as a dramatic declaration but as a lived habit.

The deeper truth is that independence enlarges what you can bring to others. It prevents collaboration from becoming conformity, and empathy from sliding into over-identification. When you are grounded in your own judgement, you free others to do the same. This is how teams become resilient and how relationships deepen: not through dependency, but through the meeting of steady, confident voices.

Reflective questions

-

Where in your life do you most rely on others’ approval, and what small step could begin to loosen that reliance?

-

How do you distinguish between healthy interdependence and dependency in your own relationships?

-

When was the last time you felt proud of a decision you made entirely on your own, and what did that experience teach you?

-

What practice could you start this week that would help you stand steadier in your own voice?

Independence is not a solo performance. It is a way of showing up whole, so that connection, collaboration, and contribution carry more weight and more honesty. When you trust your own capacity, you invite others to do the same. And from that place, shared life becomes less about reassurance and more about real partnership.

Do you have any tips or advice on raising your independence?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Independence is one of three components of the Self Expression facet from the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model, along with Emotional Expression and Assertiveness.

References

Bandura, A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Baumeister, R.F. and Vohs, K.D. (2007) ‘Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation’, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), pp.115–128.

Cohen, S. and Wills, T.A. (1985) ‘Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis’, Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), pp.310–357.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (1985) Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (2000) ‘The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior’, Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), pp.227–268.

Edmondson, A. (1999) ‘Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp.350–383.

Gross, J.J. and John, O.P. (2003) ‘Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), pp.348–362.

Janis, I.L. and Mann, L. (1977) Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York: Free Press.

Kaplan, S. (1995) ‘The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), pp.169–182.

Linehan, M.M. (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Masten, A.S. (2001) ‘Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development’, American Psychologist, 56(3), pp.227–238.

May, R. (1953) Man’s search for himself. New York: W.W. Norton.

Neff, K.D. (2003) ‘Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself’, Self and Identity, 2(2), pp.85–101.

Nguyen, T., Wright, A. and Dedding, C. (2018) ‘The role of solitude in mental health: A review of the literature’, Perspectives in Public Health, 138(1), pp.23–31.

Pennebaker, J.W. (1997) ‘Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process’, Psychological Science, 8(3), pp.162–166.

Schwartz, S.H. (1992) ‘Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries’, in Zanna, M.P. (ed.) Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 25. San Diego: Academic Press, pp.1–65.

Seligman, M.E.P. (1975) Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Sheldon, K.M. and Elliot, A.J. (1999) ‘Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), pp.482–497.

Sherman, D.K. and Cohen, G.L. (2006) ‘The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory’, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, pp.183–242.

Speed, B.C., Goldstein, B.L. and Goldfried, M.R. (2018) ‘Assertiveness training: A forgotten evidence-based treatment’, Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), pp.1–14.

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E. (2011) The EQ Edge: Emotional intelligence and your success. 3rd edn. Mississauga: Wiley.

[…] Previous Next […]

[…] Independence: Independence prevents flexibility from collapsing into people pleasing. Leaders who stay centred in their own judgement can shift without losing their point of view. Independence ensures that adaptation remains self authored rather than driven by external validation. […]

[…] components of Self Expression facet from the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model, along with Independence and […]

[…] Previous Next […]

[…] call. If everyone does not agree, they feel they have a valid reason to wait. This is a failure of Independence. True leadership requires the emotional capacity to stand alone in the gap between the old way and […]