Modern leadership demands constant decision making under uncertainty. Information moves fast, complexity is high, and pressure to act can eclipse time to think. In this environment, problem solving becomes more than an analytical skill. It is the discipline of slowing down, questioning assumptions, and finding clarity when both facts and feelings compete for attention.

In the EQ-i model, problem solving is defined as the ability to identify and define problems, generate and evaluate potential solutions, and implement effective plans of action (Stein & Book, 2011). It involves applying both logic and emotional awareness to decisions, ensuring that choices are not clouded by stress, impulse, or bias. Emotional intelligence does not replace reasoning; it strengthens it by adding insight into how emotion influences judgement.

When problem solving is weak, patterns emerge quickly. Teams make the same mistakes, just faster. Leaders jump to conclusions, confusing confidence with accuracy. Emotions like fear or frustration take over, narrowing perspective and reducing creativity. At the other extreme, overthinking paralyses progress, creating a cycle of avoidance disguised as analysis.

Effective problem solving brings balance. It allows leaders to stay calm under pressure, integrate emotion with reason, and take decisions that stand up to scrutiny. It connects emotional regulation with critical thought, creating the conditions for better outcomes and steadier leadership. In a world that rewards speed, it restores the value of clarity.

Research shows that emotionally intelligent problem solvers are better at managing stress, collaborating under pressure, and maintaining decision quality over time (Caruso & Salovey, 2004; Damasio, 1994). They recognise that emotion is not noise in the system but a source of information that, when understood, guides better choices.

Why problem solving matters

Better reasoning under pressure

By acknowledging emotional influences rather than suppressing them, leaders improve clarity, reduce bias, and make more balanced decisions.

More resilient leadership

Problem solving grounded in emotional awareness allows leaders to stay composed in uncertainty and avoid reactive decisions driven by stress or ego.

Improved collaboration

When leaders engage others in structured, emotionally aware problem solving, they strengthen trust and collective ownership of solutions.

Stronger learning cycles

Reflective problem solvers extract lessons from each challenge, creating continuous improvement rather than repeating old patterns.

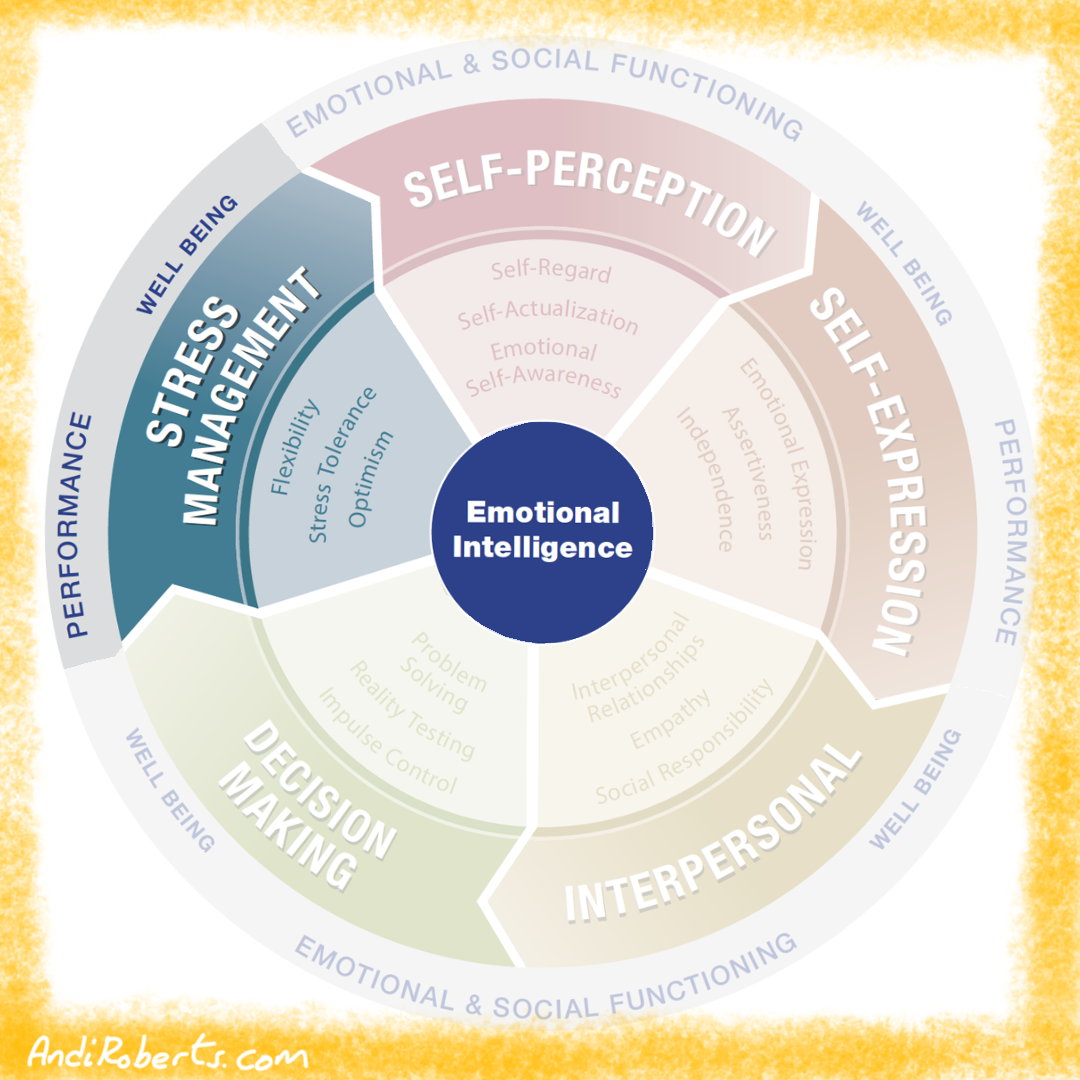

In the EQ-i framework, problem solving sits within the decision-making composite, alongside reality testing and impulse control. Together, they determine how clearly we think and how responsibly we act under pressure.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Problem solving is the capacity to think clearly, evaluate options, and move towards solutions in situations where emotion, ambiguity, and pressure are present. In the EQ-i model, it reflects not just analytical skill but the ability to manage the emotional interference that often accompanies difficult decisions. The developmental question is not whether a leader can solve problems, but how proportionately they apply effort, structure, and emotional regulation to the process. When expressed in balance, this composite supports clarity, constructive analysis, and timely decision making. When underused it results in indecision, worry, and emotional overwhelm. When overused it can become rigid, perfectionistic, or excessively detailed, slowing progress and increasing frustration. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Unable to make decisions. |

Can identify and choose the best solution. |

Spends too much time analysing problems. |

|

Worries excessively about what might go wrong. |

Faces problems head-on. |

Approaches issues so systematically that progress slows. |

|

Emotions interfere with reasoning and clarity. |

Works through frustration to address the issue at hand. |

Slow to move on or conclude, even when a decision is needed. |

|

Avoids problems until they escalate. |

Maintains emotional steadiness while problem solving. |

Overly perfectionistic or rigid in evaluating options. |

|

Depends on others to make difficult decisions. |

Able to balance emotion with evidence. |

Becomes dictatorial, insisting on a single correct way. |

Balancing factors that keep problem solving accurate and effective

In the EQ-i framework, problem solving is supported and shaped by other emotional skills that regulate how leaders interpret information, respond to pressure, and balance analysis with action. The three balancing factors below describe the emotional capabilities that keep problem solving realistic, grounded, and behaviourally effective.

Flexibility: Flexibility ensures that problem solving remains adaptive rather than rigid. Leaders who are able to shift perspective, update assumptions, and revise their approach in light of new information solve problems more effectively and avoid getting stuck in fixed patterns. Flexibility prevents over-analysis, encourages experimentation, and helps leaders move forward even when conditions are evolving or imperfect.

Reality Testing: Reality testing grounds problem solving in facts rather than assumptions or emotion. Leaders with strong reality testing distinguish clearly between what is true, what is assumed, and what is feared. This protects against catastrophic thinking, overcomplication, and the tendency to inflate threats. Accurate interpretation ensures that solutions are aligned with the actual issue rather than with imagined or exaggerated versions of it.

Emotional Self Awareness: Emotional self awareness prevents emotions from silently shaping decisions. When leaders recognise frustration, anxiety, or urgency in themselves, they are better able to prevent these emotions from distorting problem solving processes. Awareness turns emotion into data rather than interference. It allows leaders to notice when they are looping, rushing, or avoiding, and to restore clarity by separating the emotional reaction from the problem itself.

Eight practices for strengthening problem solving

Problem solving cannot be strengthened through analysis alone. It develops through repeated encounters with complexity, emotion, and uncertainty, where leaders learn to balance clarity with adaptability and evidence with intuition. In these moments, the quality of thinking is shaped as much by emotional skill as by cognitive skill.

The following eight practices cultivate the internal conditions that make effective problem solving possible. Some build awareness, such as recognising when emotion is clouding judgement. Others enhance perspective, such as grounding assumptions in reality or widening options through flexible thinking. Still others create stability, allowing leaders to approach difficult situations with steadiness rather than urgency.

Each practice follows the same structure:

Overview explains the purpose and intention.

Steps to take guide you through the core sequence.

Examples show how it works in real situations.

Variations offer ways to personalise the approach.

Why it matters roots the practice in research and insight.

Problem solving, at its heart, is not about having the quickest answer but about creating the conditions in which good judgement can emerge. It gives leaders the ability to respond with precision rather than panic, insight rather than assumption. In a world filled with complexity, it is the quiet discipline that sustains clarity.

The five whys (emotional edition)

Leaders are often trained to solve problems quickly and efficiently. Yet speed can disguise depth. Many issues persist not because solutions are poor, but because the real problem was never found. The “five whys” technique, developed in engineering and quality management, helps uncover the root cause of a problem by asking “why” several times in succession.

In emotionally intelligent problem solving, this method gains a second layer: applying it to emotions as well as facts. Leaders rarely make decisions in an emotional vacuum. Frustration, pride, anxiety, or the desire for control can all shape what feels like the “real” issue. The emotional edition of the five whys invites you to investigate not only why the problem happened but also why you feel the way you do about it.

This dual inquiry helps expose blind spots and reduces reactivity. Logical reasoning shows you what happened; emotional questioning reveals why it matters to you. When the two align, clarity follows.

Step 1: Define the visible problem

Start by writing down the issue that feels most pressing. For example: “The project deadline keeps slipping,” or “My team avoids difficult conversations.” Keep it specific and behavioural, not general or moral.

Why: Naming the visible problem clearly creates an anchor for inquiry. Without a concrete statement, your “why” questions will drift into abstraction or blame.

Step 2: Ask the first factual why

Ask yourself, “Why is this happening?” and focus only on factual or structural causes. For instance: “Because tasks are not being tracked closely,” or “Because I have not set clear expectations.”

Why: The first why usually exposes surface-level process or communication issues. This begins the logical descent into cause, helping you move from emotion to structure.

Step 3: Ask the second and third whys (beyond process)

Continue asking “why” to reveal patterns or contributing conditions. For example, “Why are tasks not tracked?” → “Because I assume everyone knows their responsibilities.” → “Why do I assume that?” → “Because I do not want to seem controlling.”

Why: By the third why, emotional and relational dynamics often appear. You begin to see how beliefs or avoidance habits contribute to the issue, revealing the emotional architecture beneath the practical one.

Step 4: Add the emotional why

Pause and ask: “Why does this situation frustrate, worry, or bother me?” This question targets your own emotional drivers. Perhaps you feel disrespected, fear being judged as weak, or dislike conflict.

Why: This is the inflection point where emotional intelligence meets analysis. By naming the emotion, you create distance from it, reducing its power to distort your judgement.

Step 5: Ask one more emotional why

Once the emotion is named, ask “Why do I feel that way?” For example, “Why do I fear conflict?” → “Because I have had experiences where speaking up led to tension.”

Why: This final layer connects current challenges to personal patterns. Recognising that your response may be about past experiences, not just the present issue, brings calm and perspective.

Step 6: Identify the integrated root

Look at your responses as a whole. Which factual and emotional causes appear repeatedly? Summarise your insight in one clear sentence: “This problem persists because we lack process clarity and I avoid reinforcing accountability to prevent discomfort.”

Why: Integrated root statements transform problem solving from surface repair to systemic understanding. Once both the operational and emotional roots are visible, more balanced and lasting solutions emerge.

Workplace examples

Team conflict

Visible problem: “Two team members keep clashing.”

Factual whys: unclear roles, ambiguous reporting lines.

Emotional whys: leader’s discomfort with confrontation.

Integrated root: “Ambiguity in roles and my avoidance of direct feedback reinforce each other.”

Missed deadlines

Visible problem: “Deadlines are repeatedly missed.”

Factual whys: overcommitment, unrealistic planning.

Emotional whys: reluctance to say no.

Integrated root: “I set unrealistic timelines to please others, then struggle to hold the line.”

Personal examples

Family logistics

Visible problem: “We keep arguing about household chores.”

Factual whys: tasks are not clearly assigned, no shared schedule.

Emotional whys: I avoid asking for help because I fear seeming demanding.

Integrated root: “Lack of a simple rota plus my reluctance to ask clearly keeps the pattern alive.”

Small action: write a shared rota and practise a clear, kind request each Sunday.

Health routine

Visible problem: “I skip evening workouts.”

Factual whys: late meetings, no preparation.

Emotional whys: I feel guilty stepping away from email.

Integrated root: “Poor planning and a belief that rest is indulgent undermine consistency.”

Small action: pack gym bag at lunch, set a 18.00 calendar block, and treat the session as recovery for tomorrow’s work.

Variations

- Team version: Facilitate a five whys session with your team, alternating between factual and emotional “whys.” This builds both operational insight and collective awareness.

- Silent version: When in a high-pressure situation, mentally ask yourself two “why” questions before reacting. Even a short pause can reveal emotional bias.

- Coach reflection: After coaching or feedback sessions, use the five whys on your own emotional responses to understand what triggered you.

Why it matters: Problem solving often falters when leaders treat emotion as interference rather than information. Research in cognitive psychology shows that emotions act as early warning systems, signalling that something matters or is at risk. When ignored, they distort reasoning; when examined, they guide it.

Using the five whys emotionally trains leaders to work with, not against, their inner responses. Over time, this builds pattern recognition: you learn which emotions reliably signal insight and which indicate bias. The result is a steadier, more truthful approach to challenges, one that balances empathy with clarity and courage with composure.

The deeper truth: The five whys works because it asks you to be honest twice. First about the mechanics of the problem, then about the meaning you attach to it. Most recurring issues are sustained by a partnership between process gaps and unspoken emotions. When you name both, you recover freedom to choose. The technique is not about blame or perfection. It is about dignity in inquiry, the courage to look beneath the surface, and the discipline to act on what you find.

Constellation mapping

When problems feel overwhelming, it is rarely because they are objectively complex. More often it is because unseen forces surround them: competing expectations, unspoken fears, subtle power dynamics, legacy decisions, organisational habits, and emotional undercurrents. These forces distort perspective, narrow thinking, and lure leaders into either over-simplifying or over-analysing. Constellation mapping gently reverses that distortion. It slows the moment, surfaces the hidden architecture around a problem, and restores clarity by making the invisible visible.

Most leaders try to solve problems from the inside out, focusing on the task itself. Constellation mapping works from the outside in. It examines the wider field affecting the challenge before attempting a solution. This broadens perspective, reduces emotional noise, and reveals leverage points that are often missed under pressure. It is not about turning every decision into a systemic analysis. It is about noticing that the system is already shaping your choices, whether you examine it or not.

Physiologically, stress shrinks attentional scope, a phenomenon well supported by research on threat perception and cognitive narrowing (Eysenck et al., 2007). Psychologically, this narrowing produces explanations that are too tight, too personal, or too linear. Constellation mapping widens the field. It reintroduces nuance. It brings back the relational, emotional, and contextual layers that were always part of the problem but rarely named. Leaders who practise this make better decisions not because they think harder, but because they think wider.

Steps to take

1 – Name the central issue

Begin by stating the problem in one clear sentence. Avoid overloading it with history or judgement. Place it in the centre of a page or board. Then pause. Notice any urge to leap into solutions. Let the problem sit without rushing to define it further.

Why: Clarity of definition reduces cognitive clutter. Naming the issue cleanly establishes an anchor point before the wider constellation is explored.

2 – Surface the surrounding forces

Around the central issue, list every force influencing it: emotional pressures, stakeholder expectations, practical constraints, timelines, fears, assumptions, hopes, incentives, previous decisions, and relational tensions. Nothing is too small. Draw each as a separate node.

Why: Problems rarely arise from one cause. By externalising the ecosystem around them, you shift from introspection to observation, lowering emotional charge and engaging more sophisticated reasoning.

3 – Map the connections

Draw lines between the forces that interact. Some reinforce each other, such as fear and perfectionism. Others contradict, such as clarity and speed. Some apply gentle pressure, others strong gravitational pull. Your aim is not precision but pattern recognition.

Why: Interconnected mapping helps the brain see structure rather than chaos. Systemic thinking increases cognitive flexibility and reduces the illusion that you must tackle everything at once.

4 – Identify leverage points

Step back and look at the constellation as a whole. Ask: “Which single force, if shifted slightly, would produce the greatest improvement?” It may be an expectation to renegotiate, a fear to acknowledge, a misaligned stakeholder to realign, or a practical constraint that can be eased.

Why: Leverage thinking prevents scattergun effort. It locates the smallest intervention that unlocks the biggest movement, conserving emotional and cognitive energy.

5 – Choose the next right action

Translate the leverage point into one concrete step: a conversation, a clarification, a request, a boundary, or a reframed assumption. Ensure the step is proportionate and executable within the next day or two.

Why: Systems thinking can feel abstract. Converting insight into action prevents intellectual overwhelm and builds confidence through movement.

Examples

Cross-functional tension: A leader thinks the issue is simply a missed deadline. Mapping reveals that fear of judgement, unclear roles, a perfectionistic culture, and silent resentment are shaping the conflict. The leverage point becomes resetting expectations and clarifying shared ownership, rather than policing timelines.

Repeated decision-stalling: An executive keeps deferring a strategic choice. The constellation shows that the block is not lack of information but concern about losing team loyalty. The next action becomes a transparent conversation, not another analysis cycle.

Customer dissatisfaction: A manager believes the main issue is product defects. The constellation reveals that inconsistent communication, over-promising, and internal misalignment all feed the problem. The biggest leverage point is setting a realistic narrative with the client.

Personal burnout: Someone assumes they are simply overloaded. Mapping uncovers people-pleasing, unclear boundaries, and fear of letting others down. The next action becomes renegotiating one commitment rather than attempting broad life change.

Variations

-

Emotional constellation: Map only the emotional forces without any operational elements.

-

Stakeholder constellation: Map people, roles, influence, and feared reactions.

-

Timeline constellation: Map how the problem evolved across weeks or months.

-

Team version: Facilitate a group mapping session where the team co-constructs the constellation.

Why it matters: Constellation mapping works because it restores perspective. It counters the brain’s tendency to narrow under stress and replaces tunnel vision with system vision. Research on complex problem solving shows that widening the frame increases accuracy, reduces emotional bias, and improves decision quality (Funke, 2010). Leaders who use this practice do not avoid problems. They contextualise them. They understand how emotion, relationship, and structure combine to shape behaviour and outcomes.

Over time, this practice builds a quiet confidence. Leaders stop assuming they must solve everything directly. They learn that many problems shift naturally when the surrounding forces change. This reduces unnecessary pressure, prevents misdiagnosis, and strengthens judgement. Teams working with such leaders feel steadier and more included, because decisions arise from a fuller view of reality rather than from rushed conclusions.

The deeper truth: Most problems are not puzzles to crack but constellations to understand. When you map them, you honour their complexity without becoming lost in it. You begin to see that solutions emerge from clarity, not urgency, and from awareness, not intensity. Each map expands your capacity to think with breadth and act with discernment. Over time, you become the kind of leader others trust when the landscape grows complicated, because you see more than the problem. You see the whole field.

Future backcasting

Most problem-solving begins at the present moment, working forward with whatever clarity, emotion, and uncertainty exist today. Yet when emotions run high or stakes feel heavy, the present becomes a distorting lens. It magnifies threat, shrinks perspective, and makes the next step feel larger or smaller than it truly is. Future backcasting reverses that lens. It begins with the successful outcome and walks backwards, step by step, until it reaches now. In doing so, it bypasses the noise of the moment and reconnects leaders with clarity, purpose, and proportion.

Backcasting draws from research on mental simulation and goal architecture, which shows that imagining the desired state in vivid detail activates cognitive pathways associated with planning and coherence rather than fear and avoidance (Taylor et al., 1998). By starting with the end state, leaders free themselves from present constraints and emotional interference, then reason backwards through the essential conditions that must be in place. The process deepens thinking by replacing reactive planning with intentional sequencing.

Future backcasting is not optimism. It is not idealistic projection. It is disciplined imagination rooted in what must be true for the best outcome to occur. It transforms overwhelmed thinking into structured clarity. Leaders who practise it develop a steadier relationship with uncertainty, because they are no longer pulled into reactive problem solving. They are guided by the architecture of the outcome itself.

Steps to take

1 – Define the successful future

Articulate what “success” looks like in one or two clean sentences. Make it concrete, observable, and emotionally grounded. Avoid the temptation to write a perfect scenario; instead, describe the outcome that would genuinely resolve the issue for the people involved.

Why: Anchoring in a clear future state calms the nervous system. Research shows that goal clarity reduces cognitive ambiguity and lowers emotional reactivity, supporting better decision making (Locke & Latham, 2002).

2 – Step back from that moment

Imagine standing just before the successful outcome became real. Ask: “What had to be in place immediately prior to this?” Identify one to three elements. These may relate to alignment, information, relationships, risk mitigation, or emotional readiness.

Why: Moving backwards disconnects the mind from present noise and re-engages planning networks that support structured thinking rather than reactive problem solving.

3 – Continue stepping back

Repeat the process, moving one layer further back. Each step should be realistic and achievable. Avoid adding complexity. Identify the essential building blocks, not an exhaustive list. Aim for three to five stages total.

Why: Backward sequencing reduces cognitive load and creates a navigable path from uncertainty to clarity. It prevents catastrophising by grounding decisions in concrete stages.

4 – Identify emotional barriers

At each stage, ask: “What emotional or cognitive trap could block this step?” It may be fear of conflict, pressure to please, perfectionism, ambiguity tolerance, or avoidance. Name each barrier and identify what would support movement past it: a conversation, boundary, clarification, or mindset shift.

Why: Emotional friction is often the real reason progress stalls. Naming it converts invisible resistance into workable insight.

5 – Convert the sequence into present action

Look at the backcast and identify the first realistic step available today. Write a one-sentence commitment: “My next move is to… because it enables the next stage of the sequence.” Keep it small enough to complete within forty-eight hours.

Why: Backcasting only creates value when it guides behaviour. The final step ensures psychological closure and forward momentum.

Examples

Strategic pivot: A leadership team feels paralysed by competing pressures. They define success as a clear, shared direction. Stepping backwards reveals that clarity requires an agreed set of decision criteria. The next step becomes facilitating a criteria-setting session, rather than debating options endlessly.

Team tension: A manager wants a collaborative, functioning team. Backcasting shows that before collaboration, psychological safety must increase. Before that, one-on-one repair conversations are needed. The first action becomes reaching out to a single team member to reopen dialogue.

Personal overwhelm: An individual aims to feel “in control” rather than constantly behind. Backcasting shows that control requires three stable routines. Before routines, they must prioritise. Before prioritisation, they need one hour of uninterrupted thinking time. The first step becomes scheduling that hour.

Customer project recovery: Success is defined as a repaired relationship and sustainable delivery rhythm. Backcasting shows that the key turning point is resetting expectations with the client. Before that, the team must align internally. The immediate action becomes holding a candid internal meeting to agree the truth of the situation.

Variations

-

Rapid backcast: A five-minute sketch for moments of acute overwhelm.

-

Team backcast: Each person defines success, then the group compares maps to reveal alignment gaps.

-

Risk backcast: Map the future and identify what could derail each step, then plan safeguards.

-

Values backcast: Define success in terms of how you want to lead, not just what you want to achieve.

Why it matters: Future backcasting strengthens problem solving by reducing emotional distortion and restoring structured reasoning. It shifts the mind from immediacy to intentionality, from reaction to design. Research on mental contrasting and implementation planning shows that combining future visualisation with backward reasoning enhances motivation, reduces avoidance, and increases solution quality (Oettingen & Gollwitzer, 2010). It also protects against common cognitive traps: short-termism, catastrophising, and false urgency.

Leaders who backcast make fewer rushed decisions because they understand the architecture of outcomes. They communicate with more steadiness because they can articulate not just what must happen, but why the sequence matters. Their teams feel calmer because direction becomes clearer, and conversation moves from drama to design.

The deeper truth: Backcasting is an act of perspective. It reminds you that the present is not the full story. You borrow clarity from the future and bring it back to guide the present. That shift turns complexity into structure, fear into information, and pressure into proportion. Over time, you become someone who navigates ambiguity not by force or speed but by design. Someone who sees beyond the immediate moment and leads from the place where clarity lives.

The left-hand column journal (emotion–fact reflection)

Every conversation has two parts: what is said aloud and what is silently thought or felt. Most misunderstandings, tensions, and missed opportunities arise not from what is spoken, but from what remains unspoken. The left-hand column journal helps leaders examine this invisible layer of communication by writing out both sides of an interaction: the outer dialogue and the inner commentary that accompanied it.

This exercise, adapted from Peter Senge’s work on reflective practice, strengthens emotional intelligence by bringing subconscious reactions into awareness. It shows how unspoken thoughts, fears, or interpretations influence your tone, decisions, and problem-solving clarity.

When leaders surface their inner dialogue, they gain insight into emotional triggers and habitual stories that distort communication. The goal is not to eliminate emotion, but to integrate it into understanding, to make your reasoning more transparent to yourself.

Step 1: Recall a recent conversation

Think of a meeting, call, or exchange that left you unsettled, confused, or frustrated. It might be a disagreement with a colleague, a client negotiation, or a feedback session. Choose one that still carries emotional charge.

Why: Emotionally charged interactions are rich learning material. They hold the greatest potential for insight into your automatic patterns and assumptions.

Step 2: Create two columns

Draw a vertical line down a sheet of paper or create a two-column table. Label the left column “What was said” and the right column “What I was thinking and feeling.”

In the left column, reconstruct the conversation as accurately as possible, using short phrases or dialogue snippets. In the right column, write your internal thoughts and emotional responses at the time.

For example:

| What was said | What I was thinking and feeling |

| “We’ll need to revisit this plan.” | “Why is he questioning me again? I’ve already done this twice.” |

| “Maybe we should involve Finance earlier.” | “Here we go, another delay. No one trusts my judgement.” |

Why: Writing both columns side by side externalises what is usually invisible. You begin to see how assumptions, fears, and irritation accompany logic. This reveals the hidden drivers of tone, defensiveness, or withdrawal.

Step 3: Step back and analyse patterns

After you have written the dialogue, read both columns slowly. Ask:

- What emotions or beliefs repeat?

- Where did I jump to conclusions or interpret motives?

- How did my inner state affect what I said next?

Why: This stage turns awareness into analysis. You are learning to identify emotional logic — the way feelings justify behaviour. Recognising these links helps you separate facts from interpretation and emotion from evidence.

Step 4: Rewrite the conversation with awareness

Now imagine replaying the same conversation, but this time with full awareness of your inner reactions. How might you express yourself differently while still being honest and respectful? What could you say aloud that would have clarified assumptions or reduced defensiveness?

Example:

Original: “We’ll need to revisit this plan.”

Response with awareness: “I hear you think Finance should be involved earlier. I feel frustrated because I believed we had alignment. Can we clarify what’s changed?”

Why: Rewriting allows emotional processing to translate into behavioural learning. It transforms raw reaction into conscious choice — the core of emotionally intelligent problem solving.

Step 5: Extract insights for future practice

Summarise what you learned. What does this reveal about your triggers, your listening habits, or your communication patterns? Note one specific action to apply next time.

For example:

- “When I feel dismissed, I tend to defend before asking questions.”

- “I often assume disagreement means criticism.”

- “I could use curiosity to slow down defensiveness.”

Why: Insight without application changes little. Each reflection builds your capacity to handle complexity without emotional distortion. Over time, this process improves both your reasoning and your relationships.

Workplace example

Context: A project leader feels undermined during a steering committee meeting.

| What was said | What I was thinking and feeling |

| “We may need to extend the timeline again.” | “They think I’m failing. I can feel my stomach drop.” |

| “What are the blockers this time?” | “Here comes the blame game. No one sees how hard we’re working.” |

| “Could we reprioritise the requirements?” | “They don’t get it. I’m too tired to argue.” |

After reflection, the leader realises that fear of criticism led to withdrawal instead of constructive dialogue. In a follow-up meeting, they share progress openly and invite joint problem solving. The result: restored trust and shared ownership of the delays.

Variations

- Email reflection: Apply the same two-column method to written exchanges. Copy the message text in the left column and your unspoken reaction in the right.

- Team debrief: In a psychological safety exercise, team members privately complete their columns, then discuss general patterns (without reading entries aloud).

- Coaching dialogue: Coaches can use the format to help leaders recognise emotional filters and practice curiosity over assumption.

Why it matters: Problem solving is not only analytical; it is relational. Every decision and conflict is influenced by invisible emotional narratives. By mapping both outer and inner dialogue, you make your own mental process transparent and accountable.

Research on reflective journaling and emotional regulation shows that naming inner thoughts reduces their intensity and improves subsequent reasoning. This method builds metacognition, awareness of your own thinking, which is central to emotionally intelligent leadership.

Over time, the left-hand column journal becomes a habit of truth-telling to yourself. You learn to notice your biases, regulate your emotions, and act with greater balance. It turns problem solving from a battle of positions into a dialogue grounded in awareness, curiosity, and respect.

The deeper truth: Every conversation has two stories. One is spoken aloud. The other runs quietly inside, shaping tone, choice of words, and willingness to listen. Most damage in problem solving does not come from the outer story but from the inner one left unexamined. The left-hand column journal makes that inner story visible. When you write it down, its grip loosens. Judgement turns into curiosity. Certainty turns into questions.

This practice is not about policing your thoughts. It is about honesty with yourself. By noticing the beliefs, fears, and assumptions that accompany your words, you recover choice in the moment. You can say what needs to be said with less defensiveness and more care. Over time, that honesty becomes steadiness. You think more clearly because you see more of what is really happening, inside you and between you and others.

The assumption testing map

Every problem exists inside a web of perspectives. When leaders make decisions, they rarely see the full picture; they see their own interpretation of it. The assumption testing map exposes the difference between what others say and what you assume they think or feel. It helps uncover bias, misplaced certainty, and emotional projection before those distort clarity or relationships.

In emotionally intelligent leadership, problem solving is not just about fixing issues but understanding the dynamics behind them. This practice allows you to map those dynamics in a structured way, identifying gaps between fact, perception, and empathy.

Step 1: Define the situation

Choose a current issue involving two or more stakeholders; a project delay, resource dispute, or strategic disagreement. Write a short factual description of what is happening, using neutral language.

Example: “Our department and Finance disagree about the timeline for approving new investments.”

Why: Stating the situation in factual terms separates the problem from blame. It creates a shared starting point for analysis rather than defence.

Step 2: Create your map

Draw a table with three columns:

- Stakeholder

- What they say or do

- What I assume they think or feel

List each stakeholder relevant to the issue, including yourself.

Example structure:

| Stakeholder | What they say or do | What I assume they think or feel |

| Me | “We need to move faster.” | I feel frustrated; I think Finance is too cautious. |

| Finance Manager | “We have to follow the review process.” | They are anxious about risk and want control. |

| Operations Lead | “Both sides are under pressure.” | They may be trying to stay neutral or avoid blame. |

Why: This table externalises invisible mental models. It transforms assumptions into visible hypotheses that can be tested rather than defended.

Step 3: Test your assumptions through dialogue or evidence

Now identify what evidence supports or contradicts your assumptions. Ask yourself:

- What proof do I actually have that they feel this way?

- Have they said it directly, or am I inferring it?

- What else could explain their behaviour?

Then, wherever possible, check your interpretation by asking questions in conversation. For instance, “I sense this process feels risky from your side, is that accurate?”

Why: Testing assumptions converts interpretation into inquiry. It strengthens empathy and reduces emotional projection. Most conflicts soften when others feel accurately understood.

Step 4: Add a fourth column for “what I learned”

After testing or reflecting, add another column:

| Stakeholder | What they say or do | What I assume they think or feel | What I learned |

| Finance Manager | “We have to follow the review process.” | I thought they wanted control. | They are worried about audit compliance, not authority. |

| Operations Lead | “Both sides are under pressure.” | I thought they were avoiding conflict. | They are genuinely trying to mediate and protect delivery. |

Why: Documenting what changes after checking builds humility and evidence-based thinking. It closes the loop between assumption and learning, turning each interaction into a source of insight.

Step 5: Identify system patterns

Step back and review your table. What does it reveal about the broader dynamics? Are your assumptions consistently shaped by distrust, urgency, or frustration? Do some roles attract projection more than others (for example, senior management, Finance, HR)?

Why: Systems thinking begins with noticing recurring interpretations. Once you see how emotional narratives repeat across contexts, you can address root causes rather than symptoms.

Workplace example

Scenario: A product launch has stalled due to conflicting priorities. The leader uses the map to clarify where misunderstanding sits.

| Stakeholder | What they say or do | What I assume they think or feel | What I learned |

| Marketing Director | “We need more time to refine the message.” | They are perfectionists and slowing things down. | They are under pressure from legal compliance to avoid false claims. |

| Sales Lead | “Clients are waiting — we should move now.” | They only care about numbers. | They are worried that delays make us lose credibility. |

| Me (Project Manager) | “We need alignment before proceeding.” | I am anxious about being blamed for missteps. | My caution is useful but needs balancing with momentum. |

By mapping both statements and feelings, the leader sees that each person’s stance protects something valid. The next meeting becomes a coordination session, not a conflict.

Personal example

Context: A friend cancels lunch twice in a row.

| Person | What they said or did | What I assumed they thought or felt | What I learned |

| Friend | “I’m sorry, work is hectic this week.” | I assumed they were avoiding me or losing interest in the friendship. | They were genuinely under pressure at work and later apologised for being distant. |

| Me | “No worries, let’s try another time.” | I felt hurt and dismissed, but didn’t say it. | I realised I tend to interpret cancellations as rejection rather than circumstance. |

This simple exercise revealed how quickly emotion coloured interpretation. By naming the assumption and verifying it, the situation shifted from insecurity to empathy.

Variations

- Team workshop: In cross-functional projects, have each member complete the map privately, then compare assumptions. The overlap and divergence reveal where alignment and misunderstanding exist.

- Coaching reflection: Use this map after difficult stakeholder interactions to identify emotional triggers and communication blind spots.

- 360-degree version: Ask trusted peers to complete a version about you, what they think you say, feel, and assume. Compare this with your own self-view for perspective calibration.

Why it matters: Leaders who fail to test assumptions often act on incomplete truths. This exercise builds the discipline of curiosity over certainty, replacing projection with empathy. It transforms conflict from a clash of positions into a process of mutual sensemaking.

Research in organisational psychology highlights that misunderstanding others’ intentions is one of the most common causes of workplace conflict. By mapping and testing assumptions, you reduce distortion and increase trust. The result is clearer dialogue, stronger collaboration, and wiser problem solving.

The deeper truth: Assumptions are the mind’s shortcuts. They help us make sense of complexity, but they also quietly narrow our field of vision. Every leader carries stories about others; who is cautious, who resists change, who lacks ambition, and these stories can become self-fulfilling.

Testing assumptions is an act of humility. It means admitting that what feels certain may not be true. It also invites courage, because it asks you to see others not as characters in your story but as thinking, feeling participants in their own.

When leaders practise assumption testing, they replace judgement with curiosity. Over time, this builds relationships grounded in trust rather than bias. It reminds us that emotional intelligence is not about controlling emotion, but about widening understanding, seeing people as they are, not just as we imagine them to be.

The six hats reappraisal

When facing complex or emotionally charged problems, leaders often rely on one habitual way of thinking. They may approach issues logically, emotionally, or cautiously, but rarely all three at once. The Six Hats Reappraisal uses Edward de Bono’s model to help you step deliberately into six distinct modes of thinking. Each “hat” gives you permission to see the same situation through a different lens, making your problem solving more balanced, creative, and emotionally intelligent.

This is not about pretending to be someone else. It is about temporarily adopting a perspective that broadens your own. Leaders who practise this technique develop stronger judgement under pressure because they can separate analysis from intuition, facts from fears, and creativity from criticism.

The six hats explained

White Hat – Facts and information: What do I know? What evidence, data, or observations are relevant? This hat disciplines your mind to separate emotion from fact. It protects against reactionary thinking.

Red Hat – Feelings and intuitions: How do I feel about this? What does my gut say? The red hat legitimises emotion as data. It ensures that instinct and empathy are acknowledged rather than hidden.

Black Hat – Risks and cautions: What could go wrong? What should we be careful of? This introduces critical evaluation, surfacing blind spots and unintended consequences.

Yellow Hat – Positives and opportunities: What could go right? What are the benefits or possibilities? The yellow hat counterbalances pessimism and reminds you to recognise potential gains and strengths.

Green Hat – Creativity and alternatives: What other options exist? What unconventional ideas could help This hat opens space for imagination, innovation, and reframing when logic alone stalls progress.

Blue Hat – Process and overview: What is the next step? How do we structure our thinking or decision? The blue hat manages the process. It helps you integrate the other perspectives into a coherent plan.

The steps to use

Step 1: Define the situation clearly

Write a short, neutral description of the issue. Keep it factual and specific.

Example: “A key project deadline was missed, and the client is unhappy.”

Why: Clarity about the problem ensures that your reappraisal focuses on reality, not emotion.

Step 2: Walk through the six hats

Set aside 10–15 minutes to move through each hat systematically. You can do this alone, with your team, or as part of a coaching reflection. For each hat, write short bullet points capturing your thoughts.

Example:

| Hat | Key insights |

| White | The delay was caused by missing data from a third-party supplier. |

| Red | I feel embarrassed and anxious about how the client perceives me. |

| Black | If this happens again, we could lose the account. |

| Yellow | The client still trusts our expertise and wants to keep working with us. |

| Green | Could we co-design a new reporting process with the supplier? |

| Blue | I will contact the supplier today, update the client transparently, and schedule a learning review. |

Why: This deliberate sequencing stops emotional thinking from dominating early. It turns problem solving into a structured conversation rather than a reactive spiral.

Step 3: Integrate the insights

Once all six hats have been explored, review your notes.

- Which hat produced the most new insight?

- Which hats do you usually avoid or overuse?

- What changes if you combine two or three perspectives instead of relying on one?

Why: Integration converts six perspectives into a single, balanced understanding. This builds emotional agility and cognitive flexibility, key capacities in the EQ-i model.

Step 4: Plan your next move

Decide one concrete step that reflects your integrated insight.

Example: “I will present the next project update using both data (White Hat) and impact stories (Yellow Hat) to address both rational and emotional needs.”

Why: Turning insight into small, specific actions ensures that reappraisal translates into behaviour, not just awareness.

Workplace example

Situation: A senior manager feels frustrated that her proposal for flexible work schedules is not progressing.

| Hat | Example reflection |

| White | The pilot data shows improved productivity but some scheduling conflicts. |

| Red | I feel discouraged because I believe in this idea strongly. |

| Black | Leadership may fear losing control or accountability. |

| Yellow | This could attract new talent and improve morale. |

| Green | What if we propose a six-month controlled experiment? |

| Blue | I will summarise these insights and discuss a revised proposal with HR. |

The structured thinking helps her reframe the issue as one of experimentation and risk management, not rejection.

Personal example

Situation: You are debating whether to confront a friend who frequently cancels plans.

| Hat | Reflection |

| White | They have cancelled three times in two months. |

| Red | I feel hurt and unimportant. |

| Black | Bringing it up could create tension. |

| Yellow | A clear conversation could strengthen honesty between us. |

| Green | Perhaps I could ask if there is something else happening in their life. |

| Blue | I will call them, share my feelings calmly, and listen. |

This shifts the tone from blame to curiosity and care.

Variations

- Team version: Assign each person a hat and have them represent that viewpoint during a meeting. Rotate roles next time.

- Crisis version: In urgent situations, use just three hats (White, Red, Blue) to balance facts, emotions, and action.

- Learning journal: Keep a “six hats diary” where you record recurring patterns, for example, noticing that you default to Black Hat caution under pressure.

Why it matters: Each hat activates a different neural pathway; analytical, emotional, creative, or integrative. Using all six prevents overreliance on any single mode of thought. For leaders, this means fewer snap judgements, more creativity under pressure, and greater emotional range in problem solving.

Research in decision science shows that people who consciously alternate between analytical and intuitive reasoning make more accurate, ethical, and confident choices. De Bono’s model provides a simple, repeatable structure for doing so.

The deeper truth: The six hats are more than a thinking tool; they are a mirror of the human mind. Facts without feeling become sterile. Feeling without facts becomes chaos. Creativity without caution becomes risk. Caution without optimism becomes paralysis.

To think fully is to move between them, to allow reason, intuition, imagination, and discipline to work together. Emotional intelligence begins where thinking becomes plural: where we can hold several kinds of truth at once without losing balance.

When leaders practise this regularly, they become calmer, more curious, and more complete thinkers. They stop reacting from habit and start responding from awareness, the essence of intelligent problem solving.

Two-door thinking

Leaders face constant decisions: when to act, when to wait, when to speak, and when to pause. In pressured environments, it is easy to rush through the first open door or freeze at the threshold. Two-door thinking introduces deliberate pacing. It separates exploration from execution, ensuring that both logic and intuition have their turn.

The image is simple. Every decision has two doors:

- Door A is the thinking door, a place for curiosity, exploration, and emotional awareness.

- Door B is the action door, the moment for clarity, commitment, and forward motion.

Moving too quickly through Door A risks impulsive action. Staying there too long leads to indecision and missed opportunities. The skill lies in knowing when reflection has done its job and when movement must begin.

Step 1: Name the decision clearly

Begin by defining the decision you are facing in one sentence. Avoid vague wording. Instead of “Should I change the team structure?”, write “Should I merge my two project teams before the new product launch?”

Then ask: What makes this decision difficult? Identify whether it is the uncertainty, the potential conflict, or fear of failure that holds you back.

Why: Precision brings emotional calm. You cannot reason about a fog; you can only walk through it once it becomes a path. Clarity about the decision anchors the process and sets the stage for genuine problem solving.

Step 2: Enter Door A – The Thinking Door

This is the reflection phase. You are not deciding; you are exploring. Use the following six questions to guide your thinking. Write your answers down to slow the process and surface assumptions.

What exactly do I know, and what do I only believe? Separate verified facts from assumptions.

What emotions are influencing me right now? Name them: fear, urgency, pride, loyalty.

What options have I not yet considered because they feel uncomfortable or unconventional? Push past the first ideas.

Who else is affected, and how might they perceive this decision? Broaden your perspective.

What evidence would genuinely change my mind? Identify what new data or feedback you would need.

What would a wiser version of me, six months from now, advise? Introduce temporal distance to balance emotion with perspective.

At this door, your goal is to stretch thinking, not to narrow it.

Why: Door A invites cognitive and emotional breadth. It balances logic with empathy, creating a more accurate picture of reality. Leaders who linger thoughtfully here often discover better options than they initially imagined.

Step 3: Recognise readiness to move

You know you are ready to move from Door A to Door B when:

- Your answers begin repeating rather than expanding.

- You can articulate one or two strong options and why they matter.

- Your emotions feel calmer and more grounded.

Pause here and write: What still feels uncertain? If the list is shorter than before, you are ready.

Why: The moment of readiness is not when you feel certain, but when you stop discovering new insight. This awareness prevents both premature action and endless analysis.

Step 4: Step through Door B – The Action Door

Door B is about movement. Reflection ends, and action begins. To enter well, use these six guiding questions:

What is the single most important objective I want this decision to achieve? Clarify intent before tactics.

What is the smallest safe step I can take to test this choice? Commit to progress, not perfection.

Who needs to know about this decision, and how will I communicate it? Include empathy in your execution.

What support or resources do I need to follow through? Anticipate constraints.

What early signs will tell me whether this was the right call? Define indicators of success or adjustment.

When will I review this decision and what I have learned? Create a feedback loop that keeps learning alive.

Why: Door B transforms reflection into momentum. It helps you act with purpose, not impulse. Leaders who clarify intent, test decisions in small steps, and schedule review points learn faster and adapt better.

Step 5: Review and refine

After action, revisit your answers. What did you discover that reflection alone could not reveal? Which emotional predictions were accurate, and which were not? Record insights in a decision log for future reference.

Why: Reflection after action closes the learning loop. Without it, experience fades into repetition rather than growth.

Workplace example

A sales director must decide whether to pursue a partnership with a new distributor.

At Door A, she distinguishes facts (the distributor’s regional reach) from assumptions (they will prioritise our brand). She realises her hesitation comes from pride, the deal originated with a junior colleague, not her. After considering others’ views and the long-term strategic fit, she feels ready to move.

At Door B, she defines her objective (“Expand market access with minimal brand risk”) and takes one step: a three-month pilot in a single territory. She shares the rationale transparently with her team and schedules a review date.

Personal example

You are deciding whether to continue in a volunteer leadership role that has become draining.

At Door A, you separate facts (hours required, outcomes achieved) from beliefs (“They will be lost without me”). You notice guilt is driving your hesitation. When you picture your future self six months on, you feel relief, not regret.

At Door B, you decide to step down but offer a month of transition support. The action feels clean rather than abrupt because thinking and emotion have already been balanced.

Variations

- Two-door journaling: Create two facing pages in a notebook, one titled “Door A: Thinking” and the other “Door B: Action.” Complete both before major decisions.

- Team exercise: In a leadership meeting, invite the team to stand physically by Door A or Door B posters depending on which phase they believe the project is in. Discuss why.

- Rapid version: For urgent situations, use three Door A and three Door B questions to ensure reflection even in speed.

Why it matters: Two-door thinking turns decision making into a rhythm instead of a reaction. Research on reflective practice and emotional regulation shows that structured pauses between reflection and execution reduce cognitive bias and decision fatigue. By deliberately answering questions at each door, leaders ground their reasoning in both logic and emotional awareness.

This structure also creates psychological safety within teams. When leaders model Door A exploration before Door B commitment, others learn that thinking aloud is valued and action is deliberate.

The deeper truth: The space between thinking and acting is where wisdom grows. Most mistakes in leadership do not come from lack of intelligence but from poor timing, acting too soon or too late. Two-door thinking trains your internal rhythm, allowing thought and courage to travel together.

Each question you ask at Door A builds depth. Each question you ask at Door B builds direction. Between them lies balance, the quiet confidence of a leader who knows that clarity is earned through reflection, and progress is achieved through movement.

The decision diary

Leaders are constantly required to make decisions, some strategic and deliberate, others fast and instinctive. Yet most never stop to track how they decide. The decision diary transforms decision making from a string of one-off events into a structured learning practice.

By recording both the thinking and feeling behind key choices before, during, and after they happen, you create a personal feedback system for your judgement. Over time, this helps you identify which emotions sharpen your reasoning and which distort it.

It is a reflective discipline grounded in emotional intelligence. Instead of treating emotion as noise in the system, it treats it as valuable data that can illuminate bias, courage, fear, or intuition.

Step 1: Set up your decision diary

Use a notebook or digital log divided into three columns:

- Before the decision – Capture your thoughts, emotions, and intentions leading up to the choice.

- At the decision moment – Record what was happening, what felt clear or uncertain, and what emotion dominated at the point of commitment.

- After the decision – Reflect on the outcome, how you now feel, and what you learned about your decision process.

Create space for each entry to include:

- Context: What decision am I facing?

- Options considered: What paths were open to me?

- Dominant emotions: What feelings were strongest?

- Rationale: Why did I choose this path?

Why: Writing forces clarity. Many leaders believe their decisions are rational until they see the emotional patterns on paper. This structure creates an ongoing mirror for self-observation.

Step 2: Capture the “before” phase

As soon as a significant decision appears, pause and capture your pre-decision state. Ask:

- What information do I have?

- What assumptions am I making?

- What am I feeling about this situation? (e.g., anxious, energised, frustrated)

- What do I fear most could happen?

- What does my intuition say?

Note both logic and emotion without judging them.

Why: This builds awareness before action. Neuroscience shows that once a decision is made, our brains tend to rewrite memory to justify it. Capturing the before phase preserves your raw thinking and emotion before they are edited by hindsight.

Step 3: Record the “decision moment”

At the point of action, when you make the call, send the email, or give the approval, record:

- What tipped the balance?

- What emotion dominated?

- Did I feel calm, pressured, or decisive?

- How confident was I (1–10)?

- Who influenced me most at this point?

You can write this immediately or soon after.

Why: The moment of decision is the bridge between reflection and action. Capturing your emotional tone and confidence level helps you see when emotion clarifies or clouds your reasoning.

Step 4: Reflect on the “after” phase

Return days or weeks later to the same decision. Add observations such as:

- What actually happened?

- What outcome did I expect versus what occurred?

- How do I now feel about the decision?

- What did I learn about my emotional accuracy?

- Would I make the same choice again?

Include both positive and negative outcomes; the goal is to learn from variance, not to seek perfection.

Why: Reflection after time has passed activates metacognition, the ability to think about your own thinking. This helps you identify emotional triggers that repeat, such as overconfidence, avoidance, or guilt-driven choices.

Step 5: Review your diary monthly

After four or five entries, step back and look across your log. Identify themes:

- Are there emotions that appear before risky or poor decisions?

- When you feel confident, is that confidence justified by outcomes?

- Do certain people or contexts consistently trigger specific feelings?

- Are there patterns of haste or hesitation?

Summarise these as personal decision-making tendencies.

Why: Over time, you create a personal evidence base for your own decision style. Awareness allows you to predict and manage emotional influences before they lead to bias.

Workplace example

A product manager keeps a decision diary over a three-month product launch.

Before one major pricing decision, he notes: “Feeling pressure from leadership to move fast. Worried about losing momentum if we delay.” At the decision moment, he records: “Went with the lower price. Relief mixed with doubt.”

A month later, reflecting back, he writes: “The price attracted many customers but squeezed margins. I realise I equated ‘speed’ with ‘success.’ Next time, I’ll separate pressure from progress.”

The diary becomes a learning record, one that tempers urgency with evidence.

Personal example

You journal about whether to accept a new job offer.

Before the decision, you write: “Feeling excited but uncertain. Worried about disappointing my current team.” At the moment of choice, you record: “Accepted. Relief and anxiety together.”

Weeks later, you reflect: “The new job is stimulating, but I underestimated how much I valued stability. My excitement masked my need for belonging.”

The log reveals that strong positive emotions can also distort realism. You start balancing enthusiasm with reflection in future moves.

Variations

- Two-column version: For quick capture, use just two columns labelled Thinking and Feeling. Log both before and after each decision to track emotional shifts.

- Team version: Encourage senior leaders to share anonymised entries during retrospectives to normalise emotional reflection in decision making.

- Prompt cards: Keep six recurring reflection questions (e.g., “What emotion drove this?” “What evidence supported my choice?”) to guide each entry.

Why it matters: A decision diary builds emotional literacy for complex leadership. It trains you to pause, notice, and integrate both cognitive and emotional inputs. Leaders who practise this method show greater adaptability, reduced decision fatigue, and improved trust from others because they act with visible self-awareness.

It also strengthens resilience. Over time, you learn that difficult emotions like doubt or anxiety do not signal weakness but information. They become cues to slow down and gather more data.

The deeper truth: The purpose of decision journaling is not to create perfect choices but to refine the chooser. Every entry is a record of how your mind and emotions dance around uncertainty.

When you can look back and see both what you thought and how you felt, you begin to understand your internal weather, when to wait, when to move, and when to trust intuition.

A leader who understands the patterns behind their decisions moves from reacting to creating. They are no longer pulled by emotion or paralysed by analysis but guided by awareness, the quiet confidence that grows from learning through reflection.

Conclusion: Thinking clearly in a noisy world

Problem solving is not simply about fixing what is broken. It is about learning to think with clarity when emotion, complexity, and pressure all compete for attention. It is the bridge between feeling and reasoning, between awareness and action. Each decision, small or large, tests your ability to stay composed, curious, and grounded in truth.

When problem solving is neglected, emotion takes the wheel. Leaders react instead of reflect, choosing what feels urgent over what is wise. Teams become caught in cycles of overanalysis or impulsivity, confusing movement with progress. Yet when problem solving is practised with emotional intelligence, decisions become both steady and human. People feel heard, assumptions are tested, and outcomes improve because they are anchored in clarity rather than noise.

The six practices in this article each strengthen a different muscle of emotional reasoning. The Five Whys (Emotional Edition) uncovers the roots beneath problems, not just their symptoms. Emotion–Fact Mapping separates data from interpretation. The Stakeholder Lens Switch broadens your field of view. The Six Hats Reappraisal trains balanced perspective. Two-Door Thinking develops foresight and emotional patience. And the Decision Diary transforms experience into learning. Together, they form a cycle of inquiry, insight, and integrity.

Problem solving is not about certainty but awareness. It asks you to listen to both logic and feeling without becoming captive to either. When you approach decisions with composure and curiosity, you turn challenges into opportunities for learning and connection. You begin to act not from pressure, but from principle.

Reflective questions

- When was the last time you took time to think through a problem rather than react to it? What difference did it make?

- Which emotions most often cloud your judgement, and how might you notice their influence earlier?

- In what kinds of problems do you tend to overthink, and in which do you decide too quickly?

- How might you use emotional signals as information rather than interference?

- Which of the six practices could help you bring more balance between head and heart in your next decision?

Problem solving begins not with analysis but with presence. The more you slow down, question assumptions, and include emotion as part of your reasoning, the wiser your choices become. Over time, this practice builds not only better outcomes but deeper trust, in your thinking, in your relationships, and in yourself.

Do you have any tips or advice for raising your problem solving capability?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Problem Solving is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Reality Testing and Impulse Control in the Decision Making facet.

Sources:

Bar-On, R. (1997) BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) Technical Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Caruso, D. R. and Salovey, P. (2004) The Emotionally Intelligent Manager: How to Develop and Use the Four Key Emotional Skills of Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Damasio, A. R. (1994) Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Avon Books.

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin.

Stein, S. J. and Book, H. E. (2006) The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons Canada.

Leave A Comment