Modern leadership involves exposure to continuous strain. Priorities shift, expectations escalate, and results are scrutinised in real time. In this climate it is easy for the emotional system to tilt towards threat interpretation. Optimism is not cheerfulness or naïve positive thinking. It is the ability to frame difficulty in a way that protects the sense of movement, meaning and capacity. It is an emotionally intelligent reconstruction of experience that stops the moment from becoming the whole story.

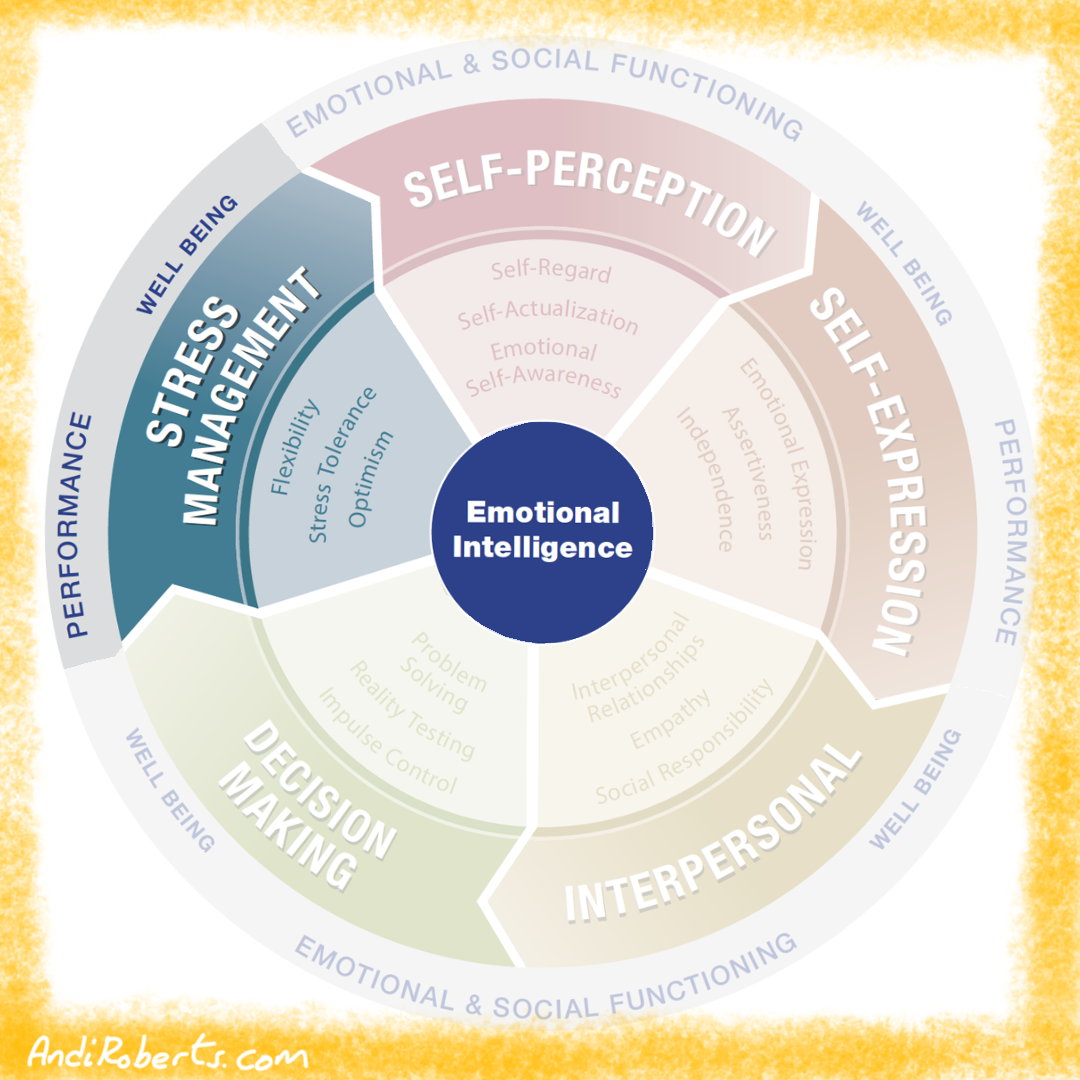

In the MHS EQ-i model, optimism refers to the capacity to maintain a constructive view of the future and to see setbacks as manageable and time limited rather than permanent and identity defining (Stein and Book, 2011). Optimistic leaders do not believe everything will work out. They believe they will remain capable of responding as events unfold. Their outlook is grounded in agency rather than hopefulness. They are able to locate meaning and learning even inside challenge. The focus is not prediction. The focus is interpretation.

Without optimism, adversity becomes personal, fixed, and global. Leaders who interpret stressors as evidence of incapacity often withdraw, catastrophise, or overcompensate. Threat responses escalate. Creativity collapses. Courage shrinks. Over time this style of emotional meaning making erodes resilience. When difficulty feels permanent, the nervous system treats it as danger rather than load (Gross, 2002; McEwen, 2007). Performance becomes fragile not because the challenges are large but because the interpretation is absolute.

With optimism, leaders stay in contact with capacity even when outcomes are uncertain. They remain anchored in what can still be influenced rather than paralysed by what has not yet worked. They notice what remains intact as well as what is at risk. They stay specific rather than global. They interpret events in ways that support action rather than shut it down. Research in resilience shows that explanatory style is one of the strongest predictors of recovery, persistence, and creative response under pressure (Bonanno, 2004; Sapolsky, 2004).

Optimism is not a bypass of reality. It is a precision lens. It protects emotional scope by keeping interpretation proportionate to the actual moment rather than the imagined future. Optimistic leaders see that setbacks are signals not verdicts. They separate identity from episode. They maintain the capacity to move towards what matters even when the path is uneven. Within the EQ-i framework, optimism strengthens stress tolerance, supports problem solving, and protects wellbeing by reducing unnecessary emotional load.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

While optimism is a constructive emotional resource, it is also a variable one. The developmental question is not simply whether a leader is optimistic, but how they hold that optimism and how proportionately it is expressed in context. This composite can strengthen resilience when realistic and grounded, but it can also become counterproductive when pessimism dominates or when positive framing drifts into denial of risk. In the EQ-i model, the effect of optimism depends on where it sits on the continuum from underuse to healthy expression to overuse. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across those three zones.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Expects that things will turn out badly. |

Holds a positive attitude even in adversity. |

Assumes things will work out regardless of evidence. |

|

Focuses on what is at risk rather than what is possible. |

Frames setbacks as temporary rather than permanent. |

Reacts positively even when seriousness is required. |

|

Interprets difficulty as identity defining rather than situational. |

Maintains confidence in their own capacity to respond. |

Minimises or ignores real problems and constraints. |

|

Limits action due to fear of negative outcomes. |

Sees possibility without denying difficulty. |

Encourages others to stay upbeat rather than addressing the issue. |

|

Uses language that closes the future such as never and always. |

Balances hope with realism and grounded assessment. |

Overpromises outcomes that are not realised. |

Balancing factors that keep optimism accurate and grounded

In the EQ-i framework, no subscale operates in isolation. Strength is always contextual and is shaped by the presence or absence of counterbalancing emotional skills. For optimism to remain constructive rather than naïve, it needs to be grounded, relationally attuned, and connected to an accurate read of the environment. The three balancing factors below describe the emotional skills that keep optimism proportionate, believable, and behaviourally useful rather than idealistic.

Self Regard: When leaders maintain a realistic sense of their worth and capability, optimism becomes grounded in agency rather than fantasy. It is not that things will be fine, it is that they believe they can influence how events unfold. This protects optimism from becoming dependent on external validation or magical thinking.

Interpersonal Relationships: Healthy relational connection ensures that optimism does not become performative positivity. Leaders with strong interpersonal skills remain sensitive to how others are experiencing the reality of the moment. They can hold hope without invalidating difficulty or bypassing emotion in the people around them.

Reality Testing: Reality testing anchors optimism in evidence. It protects against narrative inflation, wishful projection, and blind spots. When leaders compare their interpretation to actual data and observable facts, optimism becomes precise not sweeping, enabling confident movement without distortion.

Eight practices for strengthening optimism

Optimism develops through disciplined emotional meaning making. Each practice in this section explores a different aspect of interpretation: correcting time scope, focusing on what remains stable, auditing language, naming emotional drivers, tolerating imperfect outcomes, and reinterpreting meaning once the physiological wave has passed.

Each practice follows the same structure:

- Overview describes the purpose and spirit.

- Steps to take guide you through the process.

- Examples show it in real contexts.

- Variations offer options for adaptation.

- Why it matters provides the grounding in research.

Optimism is not positivity. It is the emotional precision of framing the current moment in a way that preserves future possibility.

Temporary not permanent reframing

Optimism in the EQ-i framework is not cheerfulness or enforced positivity. It is the emotional skill of interpreting events in ways that preserve personal agency, possibility, and direction in spite of setbacks (Stein and Book, 2011). It is not about assuming that outcomes will be good, but about framing difficulty in a way that keeps capacity alive. Optimism is fundamentally a process of emotional meaning making, how the mind explains adversity to itself, and that explanatory style directly shapes physiological stress response (Gross, 2002). When leaders interpret challenge as workable and time limited, the nervous system treats pressure as tolerable load rather than existential threat (McEwen, 2007). When leaders interpret difficulty as permanent and identity defining, stress becomes heavier, stickier, and more consuming.

Temporary not permanent reframing trains the leader to protect emotional scope. It shifts interpretation from “this is who I am now” to “this is what I am experiencing at this moment.” This is not delusion. It is precision. It is the discipline of describing stress in a way that keeps the future open. When optimism is grounded, it does not deny pain. It refuses to let the current state overwrite the whole story.

Steps to take

1 – Catch the first sentence: When pressure or disappointment appears, pause for one second and notice the exact internal phrase that forms. Examples: “this ruins everything,” “I always get blocked,” “this is just how it goes.”

Why: The first sentence is often the one that globalises. You cannot reframe a story you have not heard.

2 – Rewrite the scope: Write the same sentence again, but replace the permanence with time bound specificity. Change “always” to “today,” change “never works” to “not working right now.”

Why: Temporal precision reduces cognitive overreach. It shrinks threat without pretending the problem is small.

3 – Say it aloud: Read the revised sentence out loud once. Hearing the new frame activates a different neural channel than silently thinking it.

Why: Spoken language recruits prefrontal processing. This increases the likelihood of acting as if the reframing is real.

4 – Adjust posture and breath to match: Shift your physical stance to neutral. Shoulders level. Slow inhale. Full exhale. Let your physiology reflect the updated interpretation.

Why: When body and language align, the nervous system updates faster. Belief becomes embodied rather than conceptual.

5 – Return to the moment in front of you: Ask yourself: “Given this is temporary, what is one next helpful move?” Act on it within 60 seconds.

Why: A small behaviour proves that agency is intact. This seals the reframe into lived experience rather than idea.

Examples

Client pushback: A consultant receives critical feedback from a client and hears their internal voice say “this client always treats us badly.” They pause and say aloud “today they pushed hard and it felt rough.” That shift turns a permanent identity judgement into a moment in time. They recover faster and respond more constructively.

Budget delay: A leader sees a funding decision slip again and says “finance never supports us.” They reframe to “finance is delayed this month.” That temporary framing opens the door to one next step: asking what would make decision making easier next week rather than deciding the system is permanently broken.

Tough parenting evening: A parent whose teenager is withdrawn catches themselves saying “we never connect anymore.” They revise it to “tonight she was quiet and it felt hard.” This reduces despair and makes space for trying again the next afternoon rather than writing the whole relationship arc as lost.

Personal fitness dip: Someone who missed three training sessions hears their own “I am failing again.” They reframe to “this week my energy was low.” That difference supports re-entry. They are far more likely to do a gentle ten minute session tomorrow when they treat the struggle as temporary not identity defining.

Variations

Micro sticky note version: Write three temporary phrases on a post it such as “today is tough” “this is just one moment” and “this is one data point” and place it in the exact location where your stress narrative usually ignites. For example on the laptop bezel, the bathroom mirror or the car dashboard. The visual cue becomes an in situ interruptor that reminds you to correct scope in the very space the overgeneralisation arises.

Team micro contract: Agree as a team that when someone makes a globalising statement such as “this is always a nightmare” or “we never get approvals here” another member gently asks “is this forever or today?” This is not policing. It is co regulating language and protecting collective future orientation. Over time this shapes culture. The group stops predicting doom and returns to what is possible now.

Evening journalling: Each evening before bed rewrite one negatively framed sentence from the day into a temporary version. Keep both versions initial and revised side by side. This builds an archive of reframed experience. Over time leaders begin to see patterns. The mind often predicts permanence but experience rarely supports those predictions.

Future possibility micro sketch: When a difficult moment arises, after you reframe it temporarily, immediately sketch one tiny future possibility. For example “today was messy, tomorrow I can try one small behavioural adjustment.” Keep these micro sketches in a running list. This turns temporary framing into forward movement and anchors optimism in lived micro intention rather than abstract hope.

why it matters: hard moments feel heavier when the brain treats them as permanent. Temporary reframing reduces emotional flooding, increases tolerance for ambiguity, and preserves capacity to act. Research on explanatory style shows that people who habitually frame setbacks as temporary rather than fixed maintain higher resilience, better engagement, and more adaptive performance under pressure (Sapolsky, 2004; Gross, 2002).

The deeper truth: Optimism is not the belief that the future will be easy. It is the belief that the future is still open.

The deeper work here is narrative sovereignty. When a leader frames difficulty as temporary, they reclaim authorship over the meaning of the moment. They stop confusing emotional intensity with permanent identity. They stop letting one chapter dictate the entire arc. Temporary framing is not an escape from reality. It is a sober recognition that emotion is not destiny and that interpretation is a choice.

Optimism is maturity in emotional meaning making. It is the refusal to surrender the horizon.

Identify what remains unchanged

When pressure rises, the human mind instinctively scans for what is changing or under threat. This is a survival reflex. It amplifies risk so that we do not miss danger. The problem is that this reflex distorts emotional interpretation. Under stress, leaders often over focus on disruption and under recognise what remains available, stable, and still working. Optimism in the EQ-i framework is the emotional capacity to keep sight of continuity even when conditions deteriorate. It is not idealism. It is precision. It is the discipline of naming what has not collapsed, so that the nervous system does not behave as if everything has.

Identify what remains unchanged is about restoring proportion. It invites the leader to widen focus and include the elements of continuity that are still intact. This is not denial and it is not distraction. It is emotional accuracy. Even in messy moments, something will still be working. Some person will still be trustworthy. Some resource will still be accessible. Naming what is stable does not remove the difficulty. It stops the difficulty from swallowing the whole frame.

Steps to take

1 – When difficulty appears, name the disruption clearly and concisely. For example “the client pulled out of this specific meeting” or “this one milestone is now late.”

Why: Naming the disruption precisely prevents global spillage. It keeps the difficulty bounded rather than amorphous.

2 – Immediately list three things that have not changed. These could be relationships still intact, previous successes still real, resources still available, priorities still valid, or values still in place.

Why: In threat physiology the brain narrows perception. Listing what remains stable widens the lens and restores balance in emotional interpretation.

3 – State the three unchanged elements out loud, once. Use simple factual wording only.

Why: Speaking makes the stability more neurologically “real.” Language recruits rational circuitry that counters reflexive catastrophising.

4 – Choose one next step based on what is still intact. For instance, if one stakeholder remains supportive, reach out to them within the hour for a reset conversation.

Why: Behavioural movement anchored in continuity rebuilds agency faster than focusing on what is broken.

5 – Store the continuity list physically. Keep a daily continuity page in your journal or notes app. Refer back during future difficult moments.

Why: A continuity archive creates evidence for the mind that stability exists, even in volatile conditions.

Examples

Client meeting disruption: A commercial director learns that a key client has postponed an important session and feels the spike of “the whole relationship is deteriorating”. She pauses and recognises what remains intact: “the client still wants the partnership, their technical lead is still engaged, and the value case still stands”. That continuity list prevents collapse into threat thinking and she chooses one constructive action: a short check in note that same afternoon.

Project slippage: A programme lead sees one dependency slip and feels the familiar surge of “this project is unravelling”. Instead of treating the delay as total, he names what has not changed: the scope is stable, the core team is aligned, and the business case is still valid. That clarity stops rumination and he immediately books a reset session with the one stakeholder who still has capacity to help.

Parenting moment: A parent hears their own “this is getting worse every week” narrative after a tense school pick up. They pause and identify continuity: “our connection history is still real, she still jokes freely on weekends, and we still have dinner together every night”. Those anchors prevent despair and they keep the evening light instead of tightening into interrogation.

Friendship tension: After an awkward conversation, someone feels the pull of “we might not recover from this”. They deliberately locate three stable facts: “we have repaired before, our trust base is years long, and this argument was specific not global”. That steadiness stops emotional retreat and they send a short compassionate text to reopen the channel.

Variations

Continuity card: Keep an index card in your wallet with three standing anchors that are true most days such as “my capability is real,” “my network is intact,” “my health practices exist.” Use it as a reset object in stressful moments.

Continuity check with a peer: Ask a close colleague to reflect back what they see still working when you hit a difficult moment. This social mirror helps bypass your own narrowed perception.

Anchor routine: Begin key meetings that have tension with a 30 second review of what is still stable. This can be values, shared objectives, or common ground already agreed.

Continuity archive journalling: Once a week review the previous week’s disruptions and list what remained intact each time. Over time you create a personal database of continuity that reinforces emotional proportion.

Why it matters: Catastrophic interpretation is often less about severity and more about scope inflation. By deliberately naming what is unchanged, leaders reduce emotional overload, preserve executive function, and sustain adaptive action. Research in stress physiology shows that stress becomes more damaging when it is interpreted as global rather than local (Sapolsky, 2004). Restoring awareness of continuity protects capacity.

The deeper truth: Optimism is not the prediction that things will get better. It is the refusal to erase what is already stable. Identify what remains unchanged teaches the leader to hold emotional balance inside disruption. It is a disciplined act of remembering that difficulty is rarely total. There is always something that has not broken. This practice protects dignity, proportion, and hope even when conditions are demanding.

Word choice audit

Optimism in EQ-i is not the pursuit of positivity. It is the cultivation of emotionally precise interpretation. The brain does not only encode emotional states. It encodes the language used to describe those states. Words are the carrier signal of emotional meaning. Specific vocabulary changes physiological loading. Globalised vocabulary amplifies it.

Under strain the mind often defaults to high-intensity qualifiers such as always, never, everyone, ruined, impossible. These words are not data. They are stress multipliers. They convert a moment into a narrative. They turn pressure into identity-sized threat. A word choice audit restores linguistic accuracy. It trains the leader to remove catastrophic inflation from the sentence. This is emotional precision. It is not positive spin. It is accurate naming.

This practice protects scope. When the wording shrinks, the body calms. When the wording inflates, the body escalates.

Steps to take

1 – Capture the sentence in real time

When strain shows up and you hear your internal sentence shape, write the exact wording. Do not edit. Capture the native version. For example: they always block me or this is impossible.

Why: You cannot improve language you have not made observable. Language becomes editable only when it is external.

2 – Circle the intensifiers

Underline or circle the words that add scale or permanence rather than describe the event itself. Examples: always, ruined, pointless, catastrophic.

Why: Intensifiers are the distortion mechanism. They are the part of the sentence doing the emotional exaggeration.

3 – Replace intensifiers with factual anchors

Rewrite the same sentence replacing inflated terms with measurable, time bound, or observable words. For example: they delayed the response this afternoon.

Why: Replacing scope language resets the brain to accuracy. It shifts the stressor from global threat to specific moment.

4 – Test the new sentence for neutrality by reading it aloud

Read the revised sentence out loud once. The test is neutrality. It should sound like information not verdict.

Why: Speech recruits different neural circuitry. Auditory input tests whether the reframe is embodied rather than rhetorical.

5 – Choose one action that corresponds to the revised wording

Act in alignment with the new sentence. For example send one clarifying question. Ask for one missing piece of data. Make one small adjustment.

Why: Action closes the loop. The nervous system updates most when language leads to behaviour.

Examples

Contract negotiation: A sales lead hears themselves say internally: the legal team never moves. They write it down. They circle the intensifier never. They revise to: the legal team did not agree to this clause today. The new wording makes space for one productive move: ask what exact concession would make movement more acceptable tomorrow.

Cross functional dependency: A project manager thinks: this is impossible because no one supports this workflow. They audit the sentence and replace impossible and no one with specifics. Revised: two stakeholders pushed back this week. That neutral accuracy makes the next step visible: identify which stakeholder is open to testing a small pilot.

Sibling tension: A brother walks away from a family call thinking they always dismiss what I say. The audit reveals always is the amplifier. Revised: in that conversation my point did not land. The new sentence opens relational curiosity rather than fatalistic despair. Next step: ask one question next call about how his view was understood.

Personal creative block: A writer hears the globalised sentence I cannot write any more. Revision: this afternoon I struggled to complete this paragraph. That is a different emotional universe. The next step becomes small and workable: set a ten minute timer and write three sentences.

Variations

Pattern vocabulary tracker: Track and catalogue the three intensifier words you personally default to. Notice whether your stress language leans to permanence (always, never) or identity (I am useless) or futility (pointless).

Team glossary cleanse: Run a ten minute ritual at start of team retrospectives where globalised terms are replaced by factual equivalents. This trains collective linguistic hygiene.

Colour code version: Use a red pen to mark intensifiers and a green pen for factual replacements. The colour contrast helps reinforce the cognitive shift visually.

Weekly review ritual: On Friday afternoons select two sentences from the week that contained amplifying language and rewrite them accurately. This becomes a cumulative archive of scope correction.

Why it matters: Linguistic accuracy reduces threat. Catastrophic vocabulary increases physiological arousal and narrows problem solving. Calm vocabulary increases agency and restores possibility. Research in emotional meaning making shows that changing appraisal language reduces allostatic load and improves adaptive coping under pressure (Gross, 2002; McEwen, 2007).

The deeper truth: Optimism is not believing the future will be good. Optimism is refusing to let language make the present bigger than it is. Catastrophic vocabulary is a form of self intimidation. Word choice audit is narrative sovereignty. It teaches leaders to write the scale of the experience accurately so the nervous system does not pay interest on invented threat.

Specific not pervasive naming

In the middle of a stressful moment the brain tends to inflate scope. One difficulty becomes represented as everything. One sharp moment of tension becomes a totalised conclusion. This is a survival shortcut. The nervous system treats surprise or friction as a global threat to reduce the chance of being caught unprepared. In the EQ-i frame of optimism the work during stress is to keep emotional interpretation tethered to the exact event rather than letting it sprawl across identity or the future. Specific naming limits the emotional surface area. It draws a tight circle around the moment so that the rest of your life does not get unintentionally pulled into it.

Specific not pervasive naming is the discipline of describing precisely what is happening without adding generalised narrative. Rather than saying “everything is falling apart” the leader says “this one deliverable is two weeks behind our target”. The difficulty is not smaller. It is held more accurately. This accuracy keeps the nervous system calmer and preserves executive function so that the leader can remain capable inside the moment rather than consumed by it.

Steps to take

1 . Name the exact stressor: In the moment label the specific event. For example “the delay is in data validation” or “the tension is in this stakeholder disagreement”. Avoid any language that implies everywhere or always.

Why: Specificity prevents the emotional contamination that comes from treating one moment as the entire landscape.

2. Separate the stressor from self: State one sentence that differentiates the problem from identity. For example “this task is messy” not “I am messy”.

Why: Preserving identity boundaries protects confidence and capacity.

3. Separate the stressor from the future: Add a short phrase that contains the timeline. For example “this is happening this afternoon” or “this is difficult today”.

Why: The future remains open when the present is contained.

4. State one concrete observable fact: Add one real descriptor such as “we have resolved similar delays before” or “this stakeholder normally aligns after clarification”.

Why: Evidence stabilises belief far more than reassurance language.

5. Choose one live micro behaviour: Ask yourself “given the scope is specific what is one constructive move?” and take one tiny step within two minutes.

Why: Behavioural follow through converts accurate naming into agency.

Examples

Late briefing note: A manager catches herself saying “this team is always slow”. She corrects to “this briefing note from procurement is later than we expected”. One fact: “last month they delivered two days early”. She uses this grounded frame to request a single missing paragraph rather than escalate urgently.

Finance pushback: A commercial director feels the surge of “finance is impossible to deal with”. He shifts to “finance is asking for more justification for this one line item”. He recognises this is a contained moment not a permanent barrier and drafts a two sentence rationale instead of withdrawing resentfully.

Cycling race: A rider who struggles on one steep climb hears “my fitness is dropping”. They rename it to “this climb is above my usual gradient”. That accuracy prevents global judgement and they continue the ride with steady effort rather than quitting the route.

Family dinner: At dinner a parent feels “my kids never listen”. They keep scope tight. “Tonight they are tired and distracted during this meal”. That specificity keeps warmth intact and they ask one curious question rather than withdrawing.

Variations

Three words only: Capture the stressor in three literal words such as “timeline disagreement today”. This constraint forces precision.

One sentence limit: Describe the difficulty in one short sentence and forbid yourself from adding adjectives. Precision reduces emotional blowout.

Peer spotter: Ask a trusted colleague to gently reflect back when your language becomes pervasive rather than specific. It builds shared linguistic hygiene.

One minute notebook: Keep a small notebook solely for specific naming. Each stressful moment gets one line naming only the immediate event. Review weekly to see how often the brain tries to enlarge the moment.

Why it matters: Stress is amplified not only by what happens but by how it is described. Specific naming prevents cognitive magnification and keeps sense making closer to reality. In the literature on stress and appraisal specific interpretation is associated with lower cortisol responses and greater problem solving capacity under load (Gross 2002, McEwen 2007). Optimism increases when narrative stays grounded in what is actually happening rather than what the limbic system predicts.

The deeper truth: The moment is never the whole story. Specific naming is an act of emotional boundary setting. It protects the nervous system from swallowing events whole. Optimism in the EQ-i model lives in this boundary. When leaders refuse to let a single difficulty represent everything they preserve the part of themselves that can still choose.

Name the emotional drivers not just the facts

When pressure rises, the mind often reports the “facts” of the situation but hides the emotional driver beneath the surface. We say “this timeline is unrealistic” when what we actually feel is “I am afraid I will not look competent”. We say “this stakeholder is difficult” when the emotional driver is “I am worried I will be rejected again”. Optimism in the EQ-i model is grounded in whether leaders can track the emotional meaning shaping their interpretation, not just the data that appears on the surface (Stein and Book, 2011). When emotion is unacknowledged, the brain tends to treat the discomfort as threat rather than information, which amplifies stress reactivity (Gross, 2002).

Naming the emotional driver restores honest context. It reveals the internal force that is colouring the story. It protects leaders from treating discomfort as objective reality. The moment you name the emotional driver, you expand choice. Emotion is no longer manipulating the frame from the shadows. You are describing what is happening to you, not confusing it with what is happening in the world.

Steps to take

1 – State the fact in one sentence

Describe the situation using observational language only. For example “we lost two days of capacity” or “the meeting moved from Thursday to Friday.” Keep it literal, concise, and behaviour based.

Why: You must isolate the actual event before you can examine the emotional influence.

2 – Ask yourself: “what is the feeling underneath?”

Name the emotion that is colouring the interpretation: disappointment, fear of judgment, embarrassment, frustration. Be precise. Replace “stress” with the specific note: “fear of failing” “anger at being ignored” “shame that I was not ready”.

Why: Specific emotional labelling reduces amygdala reactivity and increases prefrontal control. Precision stabilises.

3 – Say both parts aloud in one sentence

For example: “the timeline moved two days and I feel afraid this will make me look incompetent.” Speak the sentence neutrally, without analysis or justification.

Why: Combining fact plus emotion in the same sentence integrates cognition and feeling instead of letting emotion distort the fact from beneath.

4 – Keep tone neutral

No dramatic voice. No heavy narrative. Say it as if you are reading a line from a script. Neutral voice prevents emotional exaggeration.

Why: Tone is a regulator. Neutral tone signals the experience is containable.

5 – Ask: “given this is the emotion, what is the smallest next constructive action?”

Do not debate the emotion. Do not try to remove it. Take one micro action: ask one clarifying question, request one data point, or move one task forward by five minutes.

Why: Action confirms agency remains intact. This protects optimism as capacity not hope.

Examples

Leadership forum tension: A senior manager notices “this room is disengaged” and then names the driver honestly: “I am afraid I am losing credibility here.” That precision prevents defensive presenting. She pauses, asks an open question, and opens the dialogue.

Stakeholder pushback: A tech lead hears himself say “this partner is being unreasonable” and the emotional driver underneath is “I feel exposed because I cannot answer everything yet.” Once that is stated internally, he relaxes his shoulders and asks one clarifying question instead of escalating.

Parenting moment: A parent thinks “my son is just being difficult again” and the emotional driver is “I feel helpless when I cannot influence him.” Naming that root feeling prevents spirals. They shift to curiosity and ask a gentle what was tough about today question.

Friend dinner: Someone interprets a friend’s short text as “they are not valuing the relationship” and the emotional driver is “I am afraid of being sidelined”. Naming this returns proportion. They decide to check in tomorrow instead of catastrophising.

Variations

Micro sentence pairing: Write one two part line each day before lunch: fact plus emotion. Example “project delayed three days. I feel anxious about pace.” This trains emotional specificity without drama.

One sentence team share: In a weekly stand up, each person shares one fact line and one emotion line about the week. It normalises emotional precision as professionalism.

Emotion vocabulary expansion: Once per week choose one new emotion word from a vocabulary list. Replace broad words like “stress” with nuanced words like “anticipation” or “disappointment”.

Future tense primer: When emotion is hot, use future tense: “I will probably feel worried for the next ten minutes.” This accepts emotion without giving it permanence.

Why it matters: Optimism is harmed most when emotion is mis-labelled or left unnamed. When feelings remain subterranean they distort interpretation and amplify perceived threat. Emotional precision reduces catastrophic appraisal and preserves access to agency (Gross, 2002). Leaders who name the driver experience lower emotional load because they are not fighting shadows. They are working with honest signals. Meaning making becomes grounded rather than fused with fear.

The deeper truth: Optimism is not about assuming good outcomes. It is about not surrendering interpretation to fear. Naming emotional drivers is a form of inner honesty. It restores authorship of meaning. It prevents feelings from secretly rewriting reality. That act is both courage and clarity. When leaders name the emotion beneath the fact, they protect possibility. They choose truth over distortion. They choose proportion over collapse. They choose agency.

Tolerance for imperfect outcomes

Optimism in the EQ-i model is not the expectation that everything will land neatly. It is the capacity to stay emotionally steady when outcomes are partial, messy, or only partly successful (Stein and Book, 2011). The nervous system prefers clean resolution. Imperfection can feel like threat because it leaves space for ambiguity and doubt. Yet most real outcomes in leadership are incremental not absolute. They move forward in fragments, improvements, tolerable steps. If a leader treats every less than ideal outcome as failure, resilience collapses. If a leader can sit with outcomes that are imperfect and still orient to value gained, agency remains fully alive.

Tolerance for imperfect outcomes is not about lowering standards. It is about interpreting reality in a proportionate way. When leaders allow “not ideal” to still count as progress, they preserve motivational fuel. They protect future orientation. They maintain the emotional elasticity needed to stay constructive through long arcs of change.

Steps to take

1 – Describe the outcome literally

State what actually happened without judgement. For example “we landed half of the client scope” or “we only finalised four of six elements”.

Why: You need a baseline before you examine meaning. Neutral description prevents unnecessary collapse.

2 – Note what value was still created

Identify one small gain: insight, data, relationship strengthening, learning, or partial movement.

Why: Attention to micro gain preserves future focus. Optimism is powered by the ability to see value even when the shape of success is uneven.

3 – Name the imperfection openly

Say a simple sentence to acknowledge what was not ideal. No inflation. No catastrophic tone.

Why: Honest naming prevents suppressed disappointment from leaking sideways into cynicism.

4 – Ask one constructive forward question

Examples: “what did this outcome make possible next?” or “what is the smallest next useful action?”

Why: Optimism is not cheerfulness. It is direction. One next move protects that direction.

5 – Mark the moment of constructive closure

Say one small sentence internally: “this outcome is workable, even if incomplete.”

Why: Closure stops rumination and restores capacity to orient forward.

Examples

Product iteration: A product team only validates two features in the sprint but they gain clarity on which user personas respond fastest. They acknowledge “we tested only part of the set” and also recognise the rapid learning. That interpretation reduces collapse and supports faster iteration next cycle.

Performance review: A leader has a review conversation that improves alignment a little but not fully. Instead of calling it “unsuccessful” they note “we improved understanding slightly today”. That framing prevents overreaction and preserves energy for next month.

Family logistics: A parent planned a calm evening routine but the evening was chaotic and only one element worked. Instead of deciding the routine idea is useless, they note “we achieved one stable step today”. They try again the next night with more patience.

Old friend reconnection: Someone reaches out to an old friend and the conversation is shorter than hoped. Instead of concluding “the friendship is gone” they name “we reconnected a little today”. They follow up in two weeks instead of withdrawing.

Variations

Micro gain log: At the end of each workday write one line: “what part of the outcome was still useful today?” A library of partial progress builds natural tolerance.

Team partial success round: In retrospectives ask the team to name one specific fragment of value from imperfect delivery. This normalises grounded optimism.

Percent shift question: After an imperfect outcome ask “did this move things even 5 percent?” Naming that small shift protects motivational momentum.

Future framing: When something lands unevenly say “this is one chapter not the whole story.” This protects proportion and future orientation.

Why it matters: Leaders who cannot tolerate imperfect outcomes treat partial progress as defeat. This kills stamina. EQ-i optimism protects stamina by maintaining proportion. Research on resilience demonstrates that meaning making around partial success predicts sustained effort more than initial confidence levels do (Gross, 2002; Bonanno, 2004). Tolerance prevents disappointment from becoming global despair.

The deeper truth: Optimism is not believing that things will always go well. It is believing that the path is still workable even when outcomes are uneven. Tolerance for imperfection is a mature form of realism. It keeps the horizon available. It recognises that progress is rarely linear and that capability grows most through iterative, imperfect movement. Leaders who tolerate imperfection do not give up early. They do not collapse meaning. They keep the future open.

Reinterpret meaning after emotion has settled

Optimism in EQ-i terms is emotional meaning making once intensity has passed. Many leaders do a post mortem on events but they do it too soon and while still emotionally charged. When adrenaline or cortisol are high, interpretation narrows and the brain defaults to threat-based story construction. The meaning made in that window is usually distorted. It feels true, but it is often temporary physiology masquerading as permanent reality.

Reinterpreting after emotion has settled is the discipline of returning to the same event the next day or even later the same day once your nervous system is quiet, and making your meaning then. It is not rewriting reality. It is deliberately separating first interpretation from final interpretation so that you do not mistake emotional residue for evidence.

Optimism is born in this gap. This is the moment where the story can be made proportionate rather than catastrophic. It is the moment where agency is retrieved.

Steps to take

1. Mark the emotion window

When the event is fresh acknowledge to yourself that you are currently in activation. You do not need to decide anything yet.

Why: Naming activation prevents premature conclusion making.

2. Schedule a revisit

Set a specific time to return to the event, ideally within twenty four hours but after the physiological spike has fallen.

Why: Psychological distance increases interpretive accuracy. Future you is a more reliable narrator.

3. Describe what happened in plain language

Write three sentences describing what occurred without interpretation or character judgement.

Why: Neutral event description becomes the anchor that protects against emotional exaggeration.

4. Name what is equally true but was hidden during the spike

Identify one stabilising fact that did not change. For example your skills, your values, your support base, or your track record.

Why: Balance requires remembering the continuity not only the disruption.

5. Craft a proportionate meaning sentence

Write one sentence that acknowledges the setback but also preserves possibility. For example: “yesterday hurt, but it is one chapter not the whole direction.”

Why: Emotion plus proportion creates grounded meaning and anchors optimism in realism.

Examples

Contract slip: Yesterday the senior client postponed signing and it felt like a total rejection. Today the leader returns to the event when calm and sees that the delay was linked to internal legal workload not dissatisfaction. Their new sentence becomes “decision making was slowed this week but the client still intends to proceed.”

Board meeting challenge: A leader was questioned harshly in a board session and felt undermined. The next morning they review the situation and recognise that three directors actually voiced support. The proportionate meaning becomes “the tension was uncomfortable but support remains present.”

Friendship strain: Someone receives a blunt message from a close friend and interprets it as abandonment. Later that evening they return, calmer, and read the message again. They see the frustration was about one specific moment not the whole relationship.

Sports setback: A cyclist underperforms in a local race and feels like their training is pointless. The next day they review the week and notice they had poor sleep. The revised meaning becomes “yesterday was a low output day but training still accumulates.”

Variations

Two day version: If the spike was high wait forty eight hours. Some events require more space for physiology to reset.

Team dual decode: In project reviews do a fast emotional reaction capture then return the next day to reinterpret together. This teaches group level emotional maturity.

Voice note method: Record a sixty second reflection during activation then another sixty seconds the next day. Compare. The difference teaches proportion.

One sentence archive: Keep a log of your proportionate reinterpretation sentences over months. This becomes a library of grounded optimism.

Why it matters: The meaning made in activation is often inaccurate. Leaders who reinterpret after emotion settles create more stable self narratives and more accurate predictions. Research on emotional regulation shows that meaning made post activation leads to more adaptive behaviour and lower stress load (Gross, 2002). This is optimism as emotional intelligence not fantasy.

The deeper truth: Optimism is not positive spin. It is choosing to assign meaning when the nervous system is quiet not when it is flooded. When leaders reinterpret only after emotion settles they protect both accuracy and hope. They let reality breathe before deciding what it means. This protects the future from being defined by the intensity of a single moment.

Future possibility micro sketch

When emotion is raw, the mind tends to over-index on the present moment. The future collapses inward and becomes hard to see. Optimism in the EQ-i framework is not expecting things to go well. It is the emotional skill of keeping the sense of possible movement alive.

This practice teaches the nervous system that even after difficult emotion there is still a next viable step ahead. It is not ambitious strategy. It is micro forward orientation. A sketch of a possible next move — not a commitment. When the future stays open by even two degrees, sympathetic load reduces. The body does not need certainty. It needs directionality.

Future possibility micro sketching works because locomotion is a core regulatory signal. The brain treats future as more tolerable when “somewhere to move next” exists. You are not deciding the future. You are leaving the aperture open.

Steps to take

1 – Wait for emotional baseline to return

Do not do this while activated. Wait until the body has cooled by at least fifty per cent and your breath has length returned. Then revisit the moment.

Why: If you sketch possibility from inside threat physiology you are still sketching the threat.

2 – Capture what mattered in the moment

Write one sentence naming the essence of why that moment felt difficult. Not the full narrative. Just the core friction point.

Why: Naming the hinge variable signals narrative clarity. You are locating the real pivot rather than replaying the blur.

3 – Identify one small direction vector

Write one tiny sentence: “one thing I could try is…”. Keep the action small enough to do in under fifteen minutes. Nothing heroic. Maintain micro-scale.

Why: The scale matters. The nervous system reads do-able action as safety. Big ambition under stress reads as threat amplification.

4 – Turn the vector into a next-step artefact

Place that micro possibility somewhere you will encounter it tomorrow: a calendar note, a reminder, a small sticky on your laptop.

Why: Embedding the future in the environment reinforces that tomorrow exists and that movement is possible.

5 – Do the micro action within forty-eight hours

Even if it is only five minutes. Do the thing. Treat it as a small rehearsal.

Why: Action is the nervous system proof that the future remained open.

Examples

Funding friction: After a bruising budget meeting, a director waits until the evening walk when their system has cooled. They write: “this felt threatening because I thought this meant the whole initiative was insecure.” Then they sketch: “one step I could take tomorrow is ask finance what one small data point would help them feel more confident in our cost assumptions.” The tiny step restores directional agency without pretending the setback was small.

Product pivot sequencing: A product lead leaves a confusing stakeholder workshop feeling stalled. Later that night they write the hinge sentence: “this felt stuck because timelines were ambiguous.” Their micro sketch becomes: “tomorrow I will schedule a ten minute call with design to align on only the next two sprints, not the whole roadmap.” That small forward anchor re-opens movement and reduces the residue of stuckness.

Parenting tension: After an argument with their teenager, a parent notices the emotional residue in their chest. Later, once settled, they write: “this felt difficult because I feared this moment meant the relationship was slipping.” The micro sketch: “tomorrow I will sit on the sofa nearby while she is doing homework and simply be available without agenda.”: It is a tiny relational direction vector, not a fix.

Personal fitness slump: After a week of missed gym sessions someone feels drop in agency. Later, once calm, they write: “this felt heavy because I feared this was the start of a decline.” Micro sketch: “tomorrow I will do five minutes of stretching while the kettle boils, nothing more.” The act is symbolic, it tells the body that motion returns.

Variations

Sticky anchor version: Write the micro sketch on a coloured sticky and place it on the laptop so that tomorrow’s version of you cannot miss it.

Calendar nudge version: Add a fifteen minute “future orientation” block tomorrow morning and put the micro sketch in the event description.

WhatsApp to future self: Send yourself a message scheduled for tomorrow with the exact one sentence “one small thing I could do is…”

Team micro horizon round: At the end of a tough week, the team each writes one micro step they will take next week that gently improves direction, not outcomes. These sit on the wall all week.

Why it matters: The future does not need to be definite for the body to down-regulate stress. It only needs to remain open. Micro possibility sketching keeps emotional aperture open. Research on stress adaptation shows that perceived future agency is a major buffer against allostatic load accumulation (McEwen, 2007; Gross, 2002). When the mind sees a plausible small step, the threat system relaxes. Hope becomes embodied not conceptual.

The deeper truth

Optimism is not “believing it will work out.” Optimism is refusing to let stress flatten the future. The deeper work here is maintaining continuity after disruption. Even if the story just cracked, you choose not to collapse the horizon line. You protect the narrative space where forward movement can return. You preserve the possibility of movement, and movement is where recovery begins.

Conclusion: The art of holding the horizon

Optimism is not about ignoring difficulty or pretending that outcomes will always land in our favour. It is the emotional discipline of holding the horizon open while working pragmatically with what is in front of us. It is the ability to interpret challenge in a way that preserves possibility. When leaders master this interpretive precision they do not deny reality. They stay connected to capacity inside it.

The practices in this section are designed to strengthen that skill. They invite you to correct the scope of your language, distinguish the moment from the identity, and locate what remains intact even in instability. Whether through reframing time boundaries, identifying stable foundations, or generating small future sketches, each exercise cultivates a form of grounded future orientation. You do not need to predict the future in order to lead toward it.

This matters because pessimistic explanatory styles quietly hollow out resilience. When setbacks are interpreted as permanent or personal the nervous system amplifies threat signals and imagination contracts. Leaders lose creative range not because the situation is impossible but because the meaning they assign to it becomes absolute. Optimism protects the capacity to learn and respond. It maintains emotional flexibility even when conditions are difficult.

Optimism also preserves wellbeing. When leaders know that difficulty is temporary, that identity is not defined by one moment, and that the future remains open to influence, they conserve emotional energy. They stay available to their team. They avoid the spiral into helplessness. They remain constructive in their response rather than captive to their fear. Teams led by such individuals learn to treat setbacks as part of progress rather than evidence of failure.

In the end, optimism is not a prediction. It is a stance. It is the emotional refusal to collapse the future into the present. It is a quiet vote for possibility even when the path ahead is uneven.

Reflective questions

- When pressure builds, what story do you tell yourself about what it means?

- Where do you tend to globalise short term difficulty into permanent limitation?

- What language do you use that closes the future before it has arrived?

- What remains intact in you even when circumstances wobble?

- What is one small act that would move you nearer to possibility this week?

Optimism is the hinge between hope and agency. It allows leaders to stay steady, resourceful, and imaginative at the same time. When you practise it you protect the capacity to move forward even in the midst of imperfect conditions.

Do you have any tips or advice on remaining optimistic?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Optimism is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Stress Tolerance and Flexibility in the Stress Management facet.

Sources:

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss trauma and human resilience. American Psychologist, 59(1), 20 to 28.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective cognitive and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281 to 291.

McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873 to 904.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Do not Get Ulcers. 3rd ed. New York: Holt.

Stein, S. J. and Book, H. E. (2011). The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. 3rd ed. Mississauga: Jossey-Bass.

[…] Previous […]

[…] is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Stress Tolerance and Optimism in the Stress […]

[…] tolerance is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Optimism and Flexibility in the Stress […]