In the noise of modern leadership, it is easy to mistake confidence for clarity. The faster decisions are made, the more tempting it becomes to rely on instinct, assumption, or emotion rather than evidence. Reality testing is the emotional intelligence skill that keeps perception honest. It is the disciplined capacity to see situations as they are, not as you hope or fear them to be.

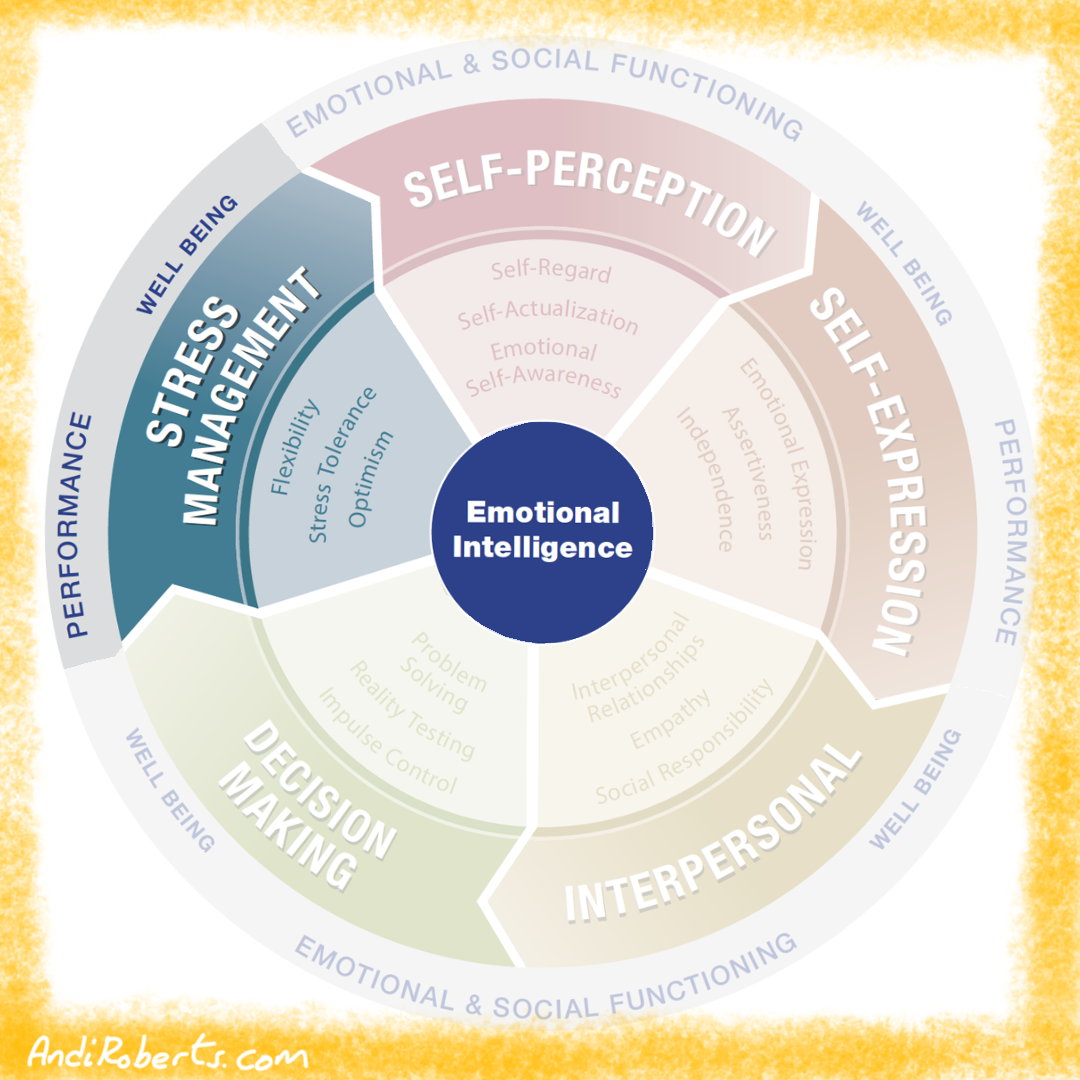

In the EQ-i model, reality testing is defined as the ability to assess the correspondence between what you experience and what actually exists (Stein & Book, 2011). It involves staying objective, checking perceptions against facts, and aligning judgement with reality. Leaders who practise strong reality testing balance intuition with verification. They seek truth before certainty and ensure that emotional reactions inform but never dictate their decisions.

When this skill is weak, distortion creeps in quietly. Decisions are shaped by mood, bias, or incomplete information. Optimism turns into denial, confidence into overreach, and caution into paralysis. Teams under such leadership often experience confusion and mistrust because words and actions no longer match observable reality. Over time, credibility erodes and alignment suffers.

By contrast, leaders who ground themselves in reality earn trust. They ask questions before giving answers, examine evidence before forming opinions, and adjust when new information appears. Their steadiness under uncertainty creates psychological safety for others. They do not rush to conclusions or defend being right; they focus on seeing clearly.

Why reality testing matters

Sound judgement under pressure

In fast-moving environments, facts can shift quickly. Leaders who practise reality testing make decisions that remain accurate even as conditions change because they separate what they know from what they believe.

Credibility and trust

When leaders align their words with what people actually experience, they build integrity. Teams learn that optimism is balanced by honesty and that commitment is matched with accuracy.

Resilience against bias

Reality testing acts as a safeguard against emotional distortion. It trains the mind to pause, observe, and question. Over time, this discipline reduces the sway of impulse, groupthink, and wishful thinking.

Clarity of perception

Seeing the world clearly is a foundation of influence. Leaders who understand how emotion shapes their perceptions can communicate with precision and lead with steadiness.

In the EQ-i framework, reality testing sits within the Decision-Making realm, alongside problem solving and impulse control. Together, these three form the core of emotionally intelligent judgement. Problem solving applies analysis, impulse control brings discipline, and reality testing grounds both in truth. Without it, even the best strategies can drift from accuracy. With it, leaders align perception with reality and action with integrity.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Reality testing is the capacity to see situations as they are rather than as emotion, bias, or fear might distort them. In the EQ-i model, it reflects the ability to anchor judgement in evidence, grounded perception, and accurate interpretation. The developmental question is not simply whether a leader is realistic, but how proportionately they apply objectivity in contexts shaped by emotion, complexity, or organisational pressure. When expressed in balance, this composite supports clarity, steadiness, and trustworthy decision making. When underused it results in idealisation, disconnection, or avoidance of difficult truths. When overused it can harden into cynicism, excessive scepticism, or a fixation on flaws that discourages progress. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Tuned out from the environment. |

Tuned into the environment and grounded in what is true. |

Plays devil’s advocate excessively. |

|

Unrealistic or overly hopeful. |

Can assess situations fairly and accurately. |

Lacks vision or becomes overly literal. |

|

Disconnected from practical realities. |

Maintains objectivity even when emotions rise. |

Deflates enthusiasm or momentum within the team. |

|

Overlooks evidence that contradicts their beliefs. |

Balances intuition with observable facts. |

Thinks in black-and-white terms. |

|

Relies on assumptions rather than truth. |

Responds proportionately to what is actually happening. |

Over-analyses, becoming cynical or pessimistic. |

Balancing factors that keep reality testing accurate and constructive

In the EQ-i framework, reality testing is shaped by other emotional skills that help leaders interpret information, regulate emotion, and maintain a grounded perspective. These balancing factors ensure that objectivity remains humane and aligned with purpose rather than overly detached or critical.

Emotional Self Awareness: Emotional self awareness helps leaders recognise when their internal state is colouring their interpretation of external events. When frustration, excitement, fear, or defensiveness rise unnoticed, perception distorts. Awareness turns these emotions into information, making it easier to separate what is felt from what is fact. This keeps reality testing clean, proportionate, and anchored in evidence rather than emotional narrative.

Self Regard: Self regard supports reality testing by helping leaders trust their own judgement without needing to exaggerate threats or minimise challenges. When leaders hold a steady sense of their strengths and limitations, they are less likely to distort reality to protect their identity. Balanced self regard promotes honest appraisal: seeing what is true without collapsing into self-criticism or inflating competence to avoid discomfort.

Problem Solving: Problem solving adds structure and clarity to reality testing. It enables leaders to translate accurate perception into meaningful action. When problem solving is strong, leaders can distinguish between surface symptoms and underlying causes, reducing the risk of misinterpretation or premature conclusions. It keeps reality testing forward-moving rather than paralysing, ensuring that truth leads to constructive progress rather than stagnation.

Eight practices for strengthening reality testing

Like all emotional intelligence skills, clarity develops through deliberate practice. The six exercises that follow are designed to help leaders recognise distortion, question assumptions, and test perceptions against evidence. Some focus on immediate awareness, such as using a quick FOG scan to separate fact from opinion. Others build reflective habits, such as keeping a weekly reality reflection log or mapping emotional triggers that distort judgement.

Each exercise follows a consistent structure:

-

Overview introduces the concept and intent.

-

Steps guide you through the process in detail.

-

Examples show how it looks in practice.

-

Variations offer adaptations for different contexts.

-

Why it matters connects the skill to research and leadership impact.

These practices are not about perfection or cold rationality. They are about developing clear sight and grounded confidence. Reality testing is the bridge between emotion and evidence. It reminds us that leadership is not the art of prediction, but of perception, and that clarity, once cultivated, becomes both a discipline and a form of care for others.

Six honest serving men

In leadership, clarity rarely comes from speed. Under pressure, leaders often mistake decisiveness for accuracy. They act from habit, emotion, or partial information, assuming their first interpretation is fact. The “Six Honest Serving Men” method, inspired by Rudyard Kipling’s six guiding questions: What, Why, When, How, Where, and Who, helps leaders pause before deciding and see the situation as it truly is.

Reality testing is not about doubt or scepticism. It is about disciplined curiosity: the ability to ask questions that strip away distortion and reveal what can be known. This practice strengthens a leader’s ability to make sound judgments under uncertainty and to act from evidence rather than assumption. Over time, it nurtures both humility and confidence, turning reactive management into reflective leadership.

Step-by-step guidance

Step 1: Frame the situation clearly and constructively

Begin by naming the specific decision or problem you face, stated in neutral, factual terms. Describe what is happening and what is at stake without exaggeration or blame. Your goal is not to explain or justify but to define what requires judgment.

Avoid emotionally charged or assumptive language such as “the team is failing” or “the client is impossible.” Instead, write one or two clear sentences that capture the observable situation and the decision it demands.

Positive leadership examples:

-

“Our new product pilot has exceeded early targets. I need to decide whether to accelerate rollout now or wait for full data from all markets.”

-

“Two high-performing team members want to lead the same initiative. I need to decide how to allocate responsibility in a way that preserves motivation and fairness.”

Challenging leadership examples:

-

“A key project is six weeks behind schedule. I need to decide whether to reassign resources, renegotiate the deadline, or reset expectations with the client.”

-

“Employee engagement scores have dropped for the second quarter. I must determine whether this signals leadership fatigue, workload imbalance, or a cultural issue.”

Why:

Framing the decision with precision turns a vague worry into a defined challenge. It anchors thinking in facts rather than emotion and sets boundaries for inquiry. By naming both what is happening and what must be decided, you create a point of focus that invites disciplined reasoning. Clarity of framing reduces reactive decisions made from frustration and increases the likelihood that subsequent analysis addresses the real issue, not a distorted version of it.

Step 2: Ask Kipling’s six questions deliberately

Take time with each one:

-

What is happening here, and what evidence supports it?

-

Why does this matter, and what outcome am I aiming for?

-

When did this begin, and when does it need to be addressed?

-

How do I know this information is true or representative?

-

Where is this most visible or misunderstood?

-

Who is affected, and who has insight I have not considered?

Why:

Each question challenges a different bias. Together, they help you balance intuition with analysis, emotion with evidence. They build a more complete view of reality that includes both facts and perspectives. Asking them slowly creates space for reflection before reaction and ensures that decisions rest on understanding rather than impulse.

Step 3: Separate facts from interpretations

Review your answers and mark each as either Fact (F) or Interpretation (I). A fact can be verified by data or observation. An interpretation is your sense-making or belief. For instance, “The team missed two deadlines” is a fact; “The team lacks motivation” is an interpretation.

Why:

The human mind naturally fills gaps with stories. This step prevents you from mistaking narrative for evidence. It helps you pause between data and conclusion, which strengthens both humility and accuracy. It also reduces conflict, since most disagreements arise from clashing interpretations, not from differing facts.

Step 4: Identify missing or untested information

Ask yourself, “What do I not yet know?” and “What might confirm or contradict my current view?” List the data, perspectives, or questions you need before making a decision.

Why:

Acknowledging uncertainty signals maturity, not weakness. This step reframes gaps in knowledge as opportunities to learn rather than obstacles to progress. It helps you avoid decisions based on incomplete information and cultivates curiosity as a leadership strength.

Step 5: Rebuild your picture of reality

Summarise what you now know to be true, what you believe, and what remains to be tested. Ask, “What possibilities does this open?” rather than “What problems remain?”

Why:

This step integrates insight and evidence into a coherent view of the situation. It encourages balanced thinking that holds both constraint and opportunity. Leaders who rebuild their picture consciously make choices that are steady, adaptive, and proportionate to reality rather than reactive to fear or pressure.

Step 6: Share your reasoning for feedback

Invite a trusted colleague, mentor, or team member to review your thinking. Ask questions such as, “What would you see differently if you were in my position?” or “What assumptions am I making?”

Why:

Opening your reasoning to others creates accountability and invites diverse input. It protects against blind spots and demonstrates humility in leadership. This kind of transparent dialogue also strengthens team culture: it shows that questioning is part of good judgment, not a threat to authority.

Examples in practice

Work example 1: A finance director hears that a regional office is overspending. Before reacting, she applies the six questions. What is being spent? Why does it matter? How do we know? She discovers that the increase came from a planned technology upgrade approved months earlier. What began as a rumour of poor management becomes recognition of proactive planning.

Work example 2: During a product review, a manager believes a new feature has failed. Applying the six questions reveals that while adoption is slow, customer satisfaction is rising steadily. The “failure” is actually early-stage adaptation. The manager reframes the narrative and protects a promising innovation.

Personal example 1: A parent assumes their teenage child is being disrespectful for avoiding conversation. Asking the six questions reveals that exams are causing stress. The parent shifts from frustration to support.

Personal example 2: A friend repeatedly cancels plans. Rather than taking offence, you apply the six questions and discover she is caring for a sick relative. The situation transforms from annoyance to empathy.

Variations and adaptations

-

The five-minute reflection: Use it immediately after a meeting or tense conversation to test assumptions.

-

Team facilitation: Have each team member answer one question before group decisions.

-

Coaching adaptation: Ask coachees to apply it to recent challenges to uncover perception distortions.

Why it matters: Reality testing is the foundation of sound judgment. Cognitive research shows that most human reasoning operates through unconscious shortcuts that prioritise speed over accuracy. Structured questioning interrupts this automatic process and brings thinking back into awareness. Leaders who practise it make decisions based on verified data, not emotional bias.

It also strengthens psychological safety. When leaders model curiosity instead of certainty, they invite others to contribute information without fear. Teams become more open, evidence-driven, and balanced in their risk assessments.

At a deeper level, reality testing supports emotional resilience. By separating facts from feelings, leaders reduce stress reactivity and maintain clarity even under pressure. It fosters confidence that is grounded in truth, not bravado. Leaders who think clearly create stability around them, enabling others to act with trust and composure.

Finally, this practice enhances moral clarity. Seeing the world as it is, rather than as we wish it to be, is an ethical act. It prevents self-deception, reduces blame, and supports fairness in decision-making. In this sense, reality testing is not just a cognitive skill but a moral discipline — the art of aligning perception with integrity.

The deeper truth: Reality testing invites leaders to practice humility before truth. It teaches that perception is never complete and that seeing clearly requires effort, patience, and courage. Every leader views the world through filters shaped by success, fear, loyalty, and identity. These filters protect us, but they can also distort what we see. The discipline of testing reality is how we learn to see through them rather than from them.

This practice is not about finding perfect certainty. It is about developing the strength to tolerate ambiguity and to stay open to correction. It reminds leaders that clarity is earned, not assumed, and that the most trustworthy confidence is built on self-scrutiny.

When leaders make a habit of testing their perceptions, they cultivate credibility. Others trust them because their confidence is quiet, transparent, and rooted in fact. Over time, reality testing becomes more than a decision skill. It becomes a way of being: a habit of mind that turns authority into stewardship and leadership into service to what is true.

FOG (Fact, Opinion, Guess) Scan

Leaders operate in constant noise: meetings, reports, and messages filled with claims, impressions, and assumptions. Under this pressure, it is easy to lose track of what is solidly known versus what is speculation or belief. The FOG Scan; short for Fact, Opinion, Guess, is a quick tool that clears this mental haze.

It helps leaders filter information in real time by categorising statements into three types:

-

Fact – What is verifiably true, based on observable evidence.

-

Opinion – A personal interpretation, preference, or judgement.

-

Guess – A hypothesis or assumption made without solid proof.

This method can be used in conversation, when reading reports, or even while thinking aloud. Its purpose is not to silence intuition but to bring awareness to the type of thinking driving each statement. The more a leader practises this distinction, the more precise and credible their reasoning becomes.

Step-by-step guidance

Step 1: Notice information flow

Before reacting to what you hear or read, pause briefly to observe the flow of statements. Notice which sound factual, which sound interpretive, and which seem uncertain.

Why:

This moment of observation activates metacognition — the ability to think about your own thinking. It slows impulsive reactions and allows you to filter information rather than absorb it uncritically.

Step 2: Label each statement as Fact, Opinion, or Guess

As you listen or read, mentally tag or highlight each key statement using F, O, or G. For example:

-

“Sales dropped by 12 per cent this quarter.” (Fact)

-

“Customers are probably unhappy with the new pricing.” (Guess)

-

“We need a stronger marketing message.” (Opinion)

Why:

Labelling creates immediate clarity. It prevents you from treating every statement as equally valid and reminds you that facts are the foundation for good judgement, while opinions and guesses require further testing.

Step 3: Test and reclassify

When uncertain about a statement’s category, ask three quick questions:

-

Can this be verified through data or observation?

-

Is this based on personal belief or interpretation?

-

Have we tested or confirmed this idea yet?

Reclassify accordingly. Encourage others to join this practice by asking, “Is that a fact or a view?” or “What evidence supports that?”

Why:

Reality testing thrives in shared language. When teams adopt FOG tagging as a normal habit, it reduces defensiveness and increases collective accuracy.

Step 4: Prioritise next actions

Once your statements are sorted, act based on category:

-

Facts anchor your immediate actions.

-

Opinions guide discussion or creative debate.

-

Guesses prompt investigation or small experiments.

Why:

Clear decisions emerge when evidence, interpretation, and uncertainty are treated differently. This step turns reflection into strategy, ensuring decisions are informed without being paralysed by data.

Examples in practice

Work example 1: A leadership team reviews a project that has gone off schedule. Instead of arguing about blame, the facilitator asks everyone to label their statements with F, O, or G. The conversation quickly reveals that many “facts” are actually guesses about other departments. Clarifying evidence allows the group to agree on next steps.

Work example 2: During a strategy review, a manager says, “Our competitors are winning because they innovate faster.” The team pauses to check the statement. It is tagged as a guess until competitive analysis confirms it. This simple act prevents the group from chasing an illusion and focuses effort where it matters.

Personal example 1: You assume a friend is avoiding you because of something you said. A FOG scan shows that this is a guess, not a fact. Checking in with them reveals they have been ill, and tension dissolves.

Personal example 2: You believe you are “bad at managing conflict.” Writing this through the FOG lens, you realise it is an opinion, not a fact. Reviewing recent conversations shows examples of you handling tension well, restoring confidence.

Variations and adaptations

-

Team dialogue version: During meetings, appoint a “FOG spotter” whose role is to track and call out statements when they drift from fact into assumption.

-

Email version: Before sending an important message or report, review key claims through FOG tagging to ensure balance between data and opinion.

-

Personal reflection: At the end of each week, choose one decision and rewrite the reasoning using F, O, and G. Notice patterns over time.

Why it matters: The FOG Scan cultivates clarity and emotional control. It trains leaders to distinguish data from drama, which reduces misunderstanding and reactive decision-making. In organisations, this habit becomes a shared discipline that improves communication and builds trust.

By separating fact, opinion, and guess, leaders create transparency in their reasoning. Others can see how conclusions are formed, which makes collaboration more respectful and less political. The result is sharper decision quality and a culture where truth is valued over certainty.

The exercise also strengthens self-regulation. Emotional triggers often arise when opinions are mistaken for facts. Recognising this distinction allows leaders to stay calm, curious, and open under pressure.

The deeper truth: In leadership, confusion between fact and belief is not just an intellectual error; it is an ethical one. When assumptions go unchecked, decisions drift away from reality and people lose confidence in those who make them.

The discipline of the FOG Scan reminds us that honesty begins with clarity. It is an act of respect to label your words truthfully, to say, “This is what I know, this is what I think, and this is what I wonder.”

Practised over time, it becomes a quiet mark of maturity. Leaders who use it regularly project steadiness. They are trusted not because they are always right, but because they are clear about what they know and what they do not.

Fact-seeking checklist

In leadership, clarity often begins not with answers but with questions. Yet under pressure, leaders can mistake speed for certainty and opinion for evidence. The fact-seeking checklist slows thinking to uncover what is truly known. It helps you separate data from assumption, observation from interpretation, and clarity from confidence.

This exercise trains disciplined curiosity. It does not seek endless data but rather the right data. By structuring inquiry through a small set of powerful questions, it helps leaders make better judgements and model transparency in how they reach conclusions. The goal is not only accuracy but trust. Teams follow those whose reasoning they can see.

Step-by-step guidance

Step 1: Define the decision or issue clearly

Start with one decision, concern, or situation that feels uncertain. Write a brief, neutral summary such as, “Our project timeline is at risk,” or, “Employee engagement has dropped.” Keep it descriptive, not diagnostic.

Why:

Clarity at the start prevents confusion later. A well-framed issue invites focus, while an emotionally charged or vague statement triggers bias. Describing without judging builds the foundation for real understanding.

Step 2: List what is known, what is believed, and what is assumed

Divide your page into three columns: Known, Believed, and Assumed. Fill in each as honestly as possible. Keep evidence separate from interpretation.

Why:

The act of writing externalises thought. It reveals how much of your reasoning rests on inference rather than proof. This step exposes hidden narratives before they distort your choices.

Step 3: Test and expand your evidence

Go through each item in your “Known” column. Ask how recent and representative the data is. Seek input from others who might see the same situation differently.

Why:

Facts without context can mislead as easily as falsehoods. Testing your evidence strengthens both accuracy and humility, reminding you that no one sees the full picture alone.

Step 4: Apply the eight-question checklist

Once you have your notes, move through the following questions one by one. Treat each as a lens, not a verdict.

The eight-question fact-seeking checklist

-

What do I know for certain, and how do I know it?

Clarify what is verifiable through direct evidence or experience.

Why: This grounds your judgement in reality rather than perception.

-

What am I treating as fact that may actually be interpretation or opinion?

Notice language that signals personal bias or untested assumption.

Why: It helps prevent emotional certainty from disguising itself as truth.

-

What assumptions or expectations am I holding, and where did they come from?

Trace patterns of thought that repeat from past experiences.

Why: It distinguishes fresh evidence from recycled stories.

-

What information is missing, unclear, or uncertain?

List what you do not yet know and where to find it.

Why: Naming uncertainty restores proportion and keeps decisions open to revision.

-

Whose perspective have I not yet heard or considered?

Identify voices outside your immediate circle.

Why: Different perspectives reveal blind spots and broaden ethical awareness.

-

What evidence could disprove or challenge my current view?

Search for data that contradicts your working assumption.

Why: Reality testing requires inviting discomfort to strengthen accuracy.

-

What patterns or signals are consistent over time, and what are exceptions?

Distinguish between recurring trends and one-off anomalies.

Why: Patterns point to systemic truth, while exceptions highlight noise.

-

What remains uncertain, and how will I monitor or test it over time?

End with a plan for observation and adjustment.

Why: Decision quality depends not only on what you know now but on how you keep learning.

Examples in practice

Work example 1: A product director assumes customer churn is due to price increases. After applying the checklist, they discover that most departures come from service dissatisfaction. Instead of cutting prices, they reinvest in customer support and reduce churn by 30 per cent.

Work example 2: A senior HR leader believes low engagement stems from workload. Fact-seeking reveals that while workload is high, the real issue is lack of recognition. By addressing appreciation rather than hours, the team culture improves rapidly.

Personal example 1: A friend seems distant, and you assume they are upset with you. On checking, you learn they are struggling with family pressures. Clarifying the facts replaces anxiety with empathy.

Personal example 2: You think a fitness plan is not working because results are slow. Reviewing facts shows progress is consistent but smaller than expected. Adjusting expectations prevents unnecessary discouragement.

Variations and adaptations

-

Team version: Use the eight questions in meetings when deciding strategy. Rotate who asks each one to create shared responsibility for accuracy.

-

Coaching version: Invite coachees to apply the checklist to emotionally charged situations where assumptions often drive reaction.

-

Rapid version: In fast-moving environments, ask aloud, “What do we know for sure?” to anchor the discussion in evidence.

Why it matters: Fact-seeking strengthens three essential leadership qualities: accuracy, composure, and credibility. It reduces emotional reasoning, protects against bias, and encourages intellectual honesty. Teams trust leaders who think visibly and invite scrutiny of their reasoning.

It also cultivates emotional intelligence. When you check facts before reacting, you regulate emotion with curiosity rather than control. This balance of logic and awareness builds resilience under pressure.

Organisationally, fact-seeking creates cultures of learning. When leaders model evidence-based thinking, teams follow suit. Meetings become inquiries rather than debates, and disagreement becomes data rather than conflict. Over time, truth becomes a shared pursuit.

The deeper truth: Fact-seeking is not a mechanical task but an act of respect, for reality, for others, and for the limits of your own certainty. It requires humility to admit what is unknown and courage to confront what is true.

Leaders who practise it consistently become known not for speed but for steadiness. Their authority does not rest on opinion but on integrity. They understand that clear sight is a form of service: to their teams, to their purpose, and to the decisions that shape lives.

Fact-seeking, at its heart, is moral clarity. It reminds us that seeing the world as it is, not as we wish it to be, is the beginning of wisdom.

Accuracy calibration

When reality becomes difficult to interpret, the problem is rarely the facts themselves. It is the confidence we place in our interpretations without checking whether they are actually accurate. Human beings consistently overestimate the correctness of their perceptions, particularly under stress, speed, or emotional load. This creates a hidden vulnerability: decisions feel grounded long before they truly are. Accuracy calibration is the practice of testing the reliability of your own judgement over time so that confidence grows from evidence, not assumption.

Most leaders try to strengthen reality testing by gathering more information or broadening perspective. Accuracy calibration works differently. It examines the track record of your interpretations, predictions, and assumptions. It transforms reality testing from a momentary skill into a longitudinal one. You are not only checking what is true now. You are checking how well your mind tends to infer truth at all. This stabilises judgement by replacing instinctive certainty with informed humility.

Cognitive science shows that people maintain stable “accuracy signatures” in how they interpret events (Kruger & Dunning, 1999; Tenney et al., 2011). Some consistently underestimate risk. Some chronically overestimate threat. Some lean towards optimism, others towards scepticism. These tendencies shape perception more strongly than the facts themselves. Accuracy calibration brings these patterns into awareness, reducing distortion and strengthening objectivity.

It is not a practice of self-doubt. It is a practice of self-knowledge. Leaders who calibrate their accuracy develop a more honest relationship with their perceptual habits, which in turn produces clearer thinking, steadier communication, and more reliable decision making.

Steps to take

1 – Capture your first interpretation

When faced with a decision, conflict, or ambiguity, pause and write down your immediate interpretation: what you think is happening, why you think it is happening, and what you expect will unfold next.

Why: First interpretations often carry emotional colour. Capturing them freezes the initial frame, giving you a baseline to test later.

2 – Identify the confidence level

Rate your confidence in your interpretation using three categories: Low, Medium, or High. Be honest. Notice whether you tend to assign high confidence quickly or default to uncertainty.

Why: Overconfidence and underconfidence each distort reality testing. Naming confidence level helps you track which way you lean.

3 – Seek light-touch verification

Before acting, test the interpretation using minimal effort: one clarifying question, one piece of data, or one external perspective. Avoid deep analysis. The goal is small accuracy checks, not solving the problem.

Why: Light verification catches major distortions early and reduces unnecessary emotional activation.

4 – Revisit the situation after the outcome

Once the situation unfolds, return to your initial note. Compare:

-

What did I get right?

-

What was off?

-

What did I overestimate or underestimate?

-

How accurate was my confidence rating?

Why: Reviewing outcomes trains the brain to update its accuracy map. Research shows that feedback loops significantly improve judgement quality over time.

5 – Track recurring patterns

Across multiple situations, look for trends. Do you consistently misread tone? Overestimate urgency? Underestimate risk? Assume worst-case scenarios? Dismiss positive signs? Spotting these patterns builds your personal accuracy signature.

Why: Accuracy signatures are stable unless made conscious. Once visible, they can be adjusted.

Examples

Interpretive bias: A leader assumes a colleague’s silence in a meeting signals disengagement. Calibration shows that silence usually means they are thinking, not withdrawing. The leader learns to ask before concluding.

Overconfidence: A manager feels certain a stakeholder will support a proposal. After several mismatches between certainty and outcome, they learn to test assumptions earlier through short alignment conversations.

Threat inflation: An executive repeatedly predicts negative reactions from the board. Accuracy calibration reveals that these reactions rarely occur. They learn to check fear-driven projections before acting.

Emotional spillover: A team member interprets neutral emails as hostile. Tracking accuracy shows these perceptions align with their stress levels, not the content. They begin verifying tone before responding.

Variations

-

Confidence audits: Review one week of decisions and rate your accuracy versus your initial confidence.

-

Team calibration: Invite peers to compare predictions before and after decisions to reveal group biases.

-

Micro-calibration: Use quick versions in meetings by silently rating confidence before speaking.

-

Scenario calibration: For high-stakes decisions, run through three “possible truths” and check which one matches your accuracy patterns.

Why it matters: Accuracy calibration strengthens reality testing by aligning confidence with evidence. It reduces perceptual distortion caused by stress, emotion, previous failures, organisational pressure, or cognitive habits. Over time, it produces leaders who are clear without being rigid, grounded without being cynical, and confident without being careless. Research consistently shows that well-calibrated individuals make better strategic decisions, handle ambiguity more effectively, and build stronger trust because their interpretations are consistently reliable.

Teams working with leaders who calibrate their accuracy feel less second-guessed, less misunderstood, and more fairly evaluated. Leaders become known not for being infallible but for being proportionate, thoughtful, and honest about their own perceptual limits. That steadiness becomes contagious.

The deeper truth: Accuracy is not simply a matter of seeing clearly. It is a matter of knowing how you see. Without calibration, the mind mistakes emotional resonance for truth and familiarity for accuracy. With calibration, perception becomes a disciplined act. You learn that clarity lives not in certainty but in the continuous correction of your own lens.

Over time, this practice reshapes identity. You become the kind of leader whose confidence is grounded, whose interpretations are trustworthy, and whose presence brings steadiness to complex situations. You are not only testing reality. You are testing the reliability of the instrument doing the testing: yourself.

Assumption busting

Assumptions are shortcuts the mind uses to make sense of complexity. They simplify decision-making, but they can also distort reality. Leaders rely on them every day, often without noticing. Some assumptions are useful; they draw on experience and pattern recognition. Others become blind spots, limiting what leaders see, how they listen, and what options they consider.

This practice helps you surface, test, and refine your assumptions. It builds the habit of curiosity before certainty, allowing decisions to be both confident and adaptable.

Steps to take

Step 1: Identify a current decision or situation

Choose a decision you are facing or one you have recently made. Write a short description of the issue and why it matters. Then, list the key beliefs or expectations you hold about it. For example:

-

“Our client prefers detailed reports.”

-

“The team resists change.”

-

“We do not have the budget for this.”

Why: Writing assumptions down externalises them. It turns implicit beliefs into visible statements that can be examined rather than acted on automatically. It also reduces the emotional charge that often accompanies uncertainty.

Step 2: Label each statement

Next to each belief, mark whether it is a fact, belief, or assumption.

-

A fact is something verifiable by evidence.

-

A belief is a conviction supported by experience but not proven.

-

An assumption is something you treat as true without checking.

Why: Labelling introduces discipline. It separates data from interpretation and highlights where your confidence might be misplaced. This is where reasoning becomes visible and open to challenge.

Step 3: Test your assumptions

For each assumption, ask:

-

What evidence supports this?

-

What evidence contradicts it?

-

What would I need to see or hear to change my mind?

-

Who else could provide a different perspective?

-

How recent is my information?

-

What might I be avoiding by holding this view?

Why: These questions simulate a feedback loop. They shift thinking from certainty to inquiry, building cognitive flexibility and open-mindedness. They also surface emotional motives that might sit beneath logical reasoning.

Step 4: Share and invite challenge

Choose one or two trusted colleagues and share your reasoning. Say something like, “I am assuming X because of Y. Does that hold up from your side?” Encourage them to offer alternative explanations or data.

Why: External feedback breaks the echo chamber of your own logic. It exposes patterns of overconfidence or bias that are hard to see from within. Inviting challenge also signals humility and strengthens team learning.

Step 5: Track assumptions over time

Keep a short “assumption log.” Record which assumptions proved accurate and which did not. Note the context and outcome. Patterns will emerge. You might find that you overestimate resistance, underestimate time, or assume alignment too easily.

Why: Tracking creates learning loops. Over time, you will spot where intuition is reliable and where it needs recalibration. This strengthens judgment under uncertainty.

Examples in practice

Work example 1: A finance director assumes her regional team is resisting a new cost-control policy. Before taking corrective action, she lists her assumptions and labels them as facts, beliefs, or guesses. “They disagree with the new model” turns out to be an assumption, not a fact. She gathers evidence and speaks to two managers. She learns the resistance is not about the policy but about unclear data flow between finance and operations. By testing the assumption, she addresses the real issue: process design, not attitude.

Work example 2: During a strategy review, a senior leader assumes the marketing team is too optimistic about next quarter’s forecasts. He writes this down, tags it as an assumption, and asks, “What evidence supports or contradicts this?” When the team shares their data sources and reasoning, he realises his view is based on last year’s underperformance, not current conditions. Together they build a joint forecast with transparent assumptions. The discussion shifts from judgment to shared inquiry.

Personal example 1: After a family conversation about moving cities, you assume your partner is completely opposed. You write this down and ask what evidence you have. When you check, you discover that they are not against moving but are anxious about schooling for the children. Clarifying assumptions allows you to move from argument to planning.

Personal example 2: You assume a close friend has lost interest in keeping in touch because they often cancel plans. Instead of accepting the story, you share your assumption: “I am assuming you are pulling away. Is that right?” The friend explains that they are exhausted from a new job. The assumption dissolves, replaced by understanding and empathy.

Variations

1. Team version: “Assumption wall”

Gather your team and write down assumptions about a shared project, goal, or stakeholder on sticky notes. Label each as fact, belief, or assumption. Discuss which ones need testing. This collective visibility reduces groupthink and improves strategic alignment.

2. “Red team” challenge

Ask a trusted colleague to play the role of a constructive sceptic. Their task is to find flaws or missing perspectives in your reasoning. Listen without defence. This builds resilience to challenge and sharpens your ability to argue from evidence rather than emotion.

3. Pre-mortem lens

Imagine your decision has failed spectacularly. Write a short story explaining why. The reasons you invent will reveal the assumptions most likely to need testing. This method is especially effective for complex or high-stakes decisions.

Why it matters: Unchecked assumptions drive many leadership misjudgements. When people act on untested beliefs, they often misread others’ intentions, miscalculate risks, or overcommit resources. Developing assumption awareness transforms decision-making from reactive to reflective. It encourages leaders to think aloud, validate interpretations, and remain open to correction.

Teams led this way experience greater psychological safety because leaders model humility and curiosity instead of defensive certainty. This creates a culture where truth can be spoken without fear, and ideas can evolve without ego. Over time, it builds sharper collective intelligence and more grounded confidence.

The deeper truth: Reality testing is not about erasing assumptions but about making them visible. Every decision requires hypothesis. The difference between a wise leader and a rigid one is transparency: the willingness to expose your reasoning to inquiry.

When you treat assumptions as working theories rather than fixed truths, you make space for learning. Over time, this mindset shifts leadership from proving to improving, from defending what you think to discovering what is real.

Leaders who practise assumption awareness communicate with greater integrity. Their confidence is grounded not in being right, but in staying open. That balance of conviction and curiosity is what earns enduring trust.

Would you like me to now proceed to Exercise 6: Reality reflection log (the final one for the “Reality Testing” series), matching this exact level of depth, section structure, and tone?

Evidence ledger

The mind is a powerful storyteller. It weaves fragments of data, emotion, memory, and assumption into a narrative that feels coherent long before it is accurate. Under stress, this tendency accelerates. We mistake impressions for facts, fears for likelihoods, and interpretations for reality. The result is a form of perceptual inflation: the story grows faster than the evidence. An evidence ledger slows that inflation. It externalises thinking, separates what is known from what is imagined, and replaces certainty born of emotion with clarity rooted in verification.

Most leaders try to correct misinterpretation by gathering more information. But more information does not guarantee better judgement if the mind blends fact with assumption before the data is even processed. The evidence ledger works differently. It forces a structural separation between what is verified and what is hypothesised. This quiet distinction restores objectivity, reduces emotional loading, and strengthens decision quality.

Psychology shows that humans conflate inference with perception because the brain prefers complete stories to incomplete ones (Kahneman, 2011). When we lack information, the mind fills gaps with familiar patterns, past experiences, or emotional predictions. Neuroscience also demonstrates that fear and stress reduce the brain’s capacity to discriminate between fact and interpretation (Phelps et al., 2014). The evidence ledger counteracts these tendencies by slowing cognition, creating visual distance, and inviting a more disciplined relationship with truth.

This practice is not about scepticism or detachment. It is about precision. It ensures that decisions rest on what is real rather than what is merely plausible, familiar, or emotionally charged. Leaders who use this approach become known for fairness, proportion, and steadiness of judgement.

Steps to take

1 – Divide the page

Draw a line down the centre of a sheet of paper. Label the left column Verified Evidence and the right column Unverified Assumptions. Commit to keeping the boundary strict, even if it feels uncomfortable.

Why: Physical separation reduces cognitive fusion, a phenomenon where the brain merges perception with interpretation. Externalising the categories is the first step toward clarity.

2 – Populate the evidence column

Fill the left column with information that is objectively confirmed. This includes observable behaviours, reliable data, direct statements, documented timelines, and first-hand experience. Use bullet points and keep each entry short.

Why: This builds an anchor of certainty in situations where emotion or ambiguity may distort interpretation. Seeing verified facts collected in one place lowers anxiety and improves proportionality.

3 – Populate the assumptions column

List everything you believe might be true but cannot yet confirm: interpretations, fears, hypotheses, patterns, motives, and predictions. Resist the urge to justify or refine them. Capture them as they arise.

Why: Assumptions are not wrong; they are simply untested. Listing them prevents them from silently masquerading as facts and shaping decisions prematurely.

4 – Mark your emotional load

Scan both columns and underline any item that carries emotional weight. These are often the entries that distort clarity the most. Note whether the emotional load sits more heavily on the evidence or the assumptions.

Why: Emotional tagging exposes where feelings have become entangled with thought. Naming the entanglement reduces its grip and restores objectivity.

5 – Test one assumption at a time

Choose a single assumption and ask:

-

“What evidence would confirm this?”

-

“What evidence would disconfirm it?”

-

“What is the least effortful way to check it?”

Then take the smallest verification step available: a clarifying question, a data check, a brief conversation, or a review of past patterns.

Why: Incremental testing avoids overwhelm and prevents decision paralysis. Small checks correct the story gently without destabilising confidence.

Examples

Misinterpreted silence: A leader assumes a colleague is disengaged because they are quiet in meetings. The evidence ledger shows that the only verified fact is silence. The assumption column reveals interpretation, not proof. A simple check (“How are you finding these discussions?”) uncovers that the colleague is processing, not withdrawing.

Perceived urgency: A manager believes a stakeholder is unhappy because they requested an update. The ledger shows that the request is evidence, but unhappiness is assumption. Follow-up reveals routine information gathering, not concern.

Team conflict: An executive interprets resistance to a new process as defiance. The evidence column shows slower adoption. The assumption column shows projected intent. Verification uncovers confusion, not opposition.

Self-doubt: Someone assumes their performance was subpar in a presentation. Evidence shows positive comments and successful delivery. Assumptions reveal internal criticism and emotional residue. The ledger exposes the gap.

Variations

-

Three-column version: Add a third column for “Evidence I Need” to guide follow-up.

-

Team ledger: Use collectively to separate organisational truth from group speculation.

-

Rapid ledger: Create a ninety-second version during meetings when narrative drift begins.

-

Emotional ledger: List facts versus feelings to clarify how emotion colours interpretation.

Why it matters: The evidence ledger strengthens reality testing by interrupting narrative momentum, a cognitive process where assumptions gain the force of truth simply through repetition. It prevents leaders from making decisions based on incomplete or emotionally loaded stories. Research shows that people who distinguish fact from inference make more accurate judgements, reduce interpersonal conflict, and maintain healthier stress regulation (Lieberman et al., 2007; Tenney et al., 2011).

Over time, this practice builds a more discerning mind. Leaders become less reactive, more proportionate, and more willing to verify instead of assume. Their decisions improve, their relationships deepen, and their communication becomes clearer and more grounded. Teams trust them because they do not jump to conclusions or confuse speculation with reality.

The deeper truth\: An evidence ledger is ultimately a practice in intellectual honesty. It asks leaders to face the limits of what they know and to resist the comfort of premature certainty. It teaches that clarity does not come from knowing more but from distinguishing carefully between the known and the untested.

With repetition, this practice reshapes identity. You become a leader whose interpretations are measured, whose confidence is trustworthy, and whose presence brings calm to complexity. You stop being ruled by stories your mind creates under pressure. Instead, you choose which stories to validate, which to question, and which to release entirely.

You are not just seeking truth. You are learning to honour it.

Multiple-lens review

Sound judgement depends on the ability to see clearly from different perspectives. Most leaders default to one habitual frame: data, urgency, or intuition. A multiple-lens review interrupts that pattern. It provides structured ways to test perception before acting, ensuring that decisions are grounded in evidence, context, and awareness of human impact.

This exercise invites you to explore reality through a set of lenses: Decision Impact, Four Realities, Six Perspectives, and an added Emotional Lens. Each one highlights a different truth; what is known, what is assumed, what patterns exist, and how people feel. Together, they build balanced, self-aware thinking.

Steps to take

Step 1: Define the decision or problem clearly

Write one short, factual sentence describing the issue you want to examine. Keep emotion and blame out of it.

Examples:

-

“The product launch has slipped by three weeks and clients are becoming anxious.”

-

“Our department needs to reduce costs without damaging morale.”

Why: Clarity is the first act of leadership. A neutral statement prevents the story in your head from distorting what is actually happening.

Step 2: Apply the lenses

Use all of the lenses or select those most useful to your situation. Work through each one, noting observations, questions, and tensions.

The Decision Impact Lenses

|

Lens |

Guiding question |

Why it helps |

|---|---|---|

|

Evidence |

What do I know for certain? What is assumption or guesswork? |

Keeps conclusions anchored in verifiable facts. |

|

Stakeholder |

Who will be affected and how will they likely respond? |

Surfaces relational and reputational effects. |

|

Risk |

What could go wrong and how reversible is it? |

Builds prudence into confidence. |

|

Values |

Does this align with our shared principles and purpose? |

Prevents ethical drift under pressure. |

|

Adaptability |

How flexible is this choice if conditions change? |

Encourages resilience and contingency thinking. |

|

Timing |

Is this the right moment to act? |

Guards against both haste and paralysis. |

|

Emotional |

What emotions are shaping this choice in me or others? |

Brings hidden emotional data into conscious review. |

The Four Realities Lens

|

Lens |

Guiding question |

Why it helps |

|---|---|---|

|

Event reality |

What is happening right now that can be observed? |

Reduces speculation and anchors perception in fact. |

|

Pattern reality |

What recurring behaviours or results can I see? |

Identifies deeper rhythms behind single events. |

|

Structure reality |

What systems or incentives sustain these patterns? |

Directs attention to causes rather than symptoms. |

|

Mental-model reality |

What beliefs or assumptions are shaping perception or action? |

Makes invisible thinking visible and testable. |

|

Emotional reality |

What is the emotional tone of the situation? |

Adds awareness of mood, morale, and unspoken tension. |

The Six Perspectives Lens

|

Lens |

Guiding question |

Why it helps |

|---|---|---|

|

Self (I) |

What is happening within me as I face this issue? |

Builds awareness of personal bias and energy. |

|

Relationship (We) |

How is this experienced between people or groups? |

Illuminates connection, trust, and dialogue. |

|

Behaviour (It) |

What can be seen or measured objectively? |

Grounds understanding in evidence, not opinion. |

|

System (Its) |

What cultural or organisational structures shape behaviour? |

Reveals forces beyond individual control. |

|

Ethical |

What response would be fair and responsible? |

Keeps conscience and accountability visible. |

|

Time |

How might this look now, soon, and later? |

Encourages sustainable, future-ready choices. |

|

Emotional |

What feelings or emotional dynamics are influencing judgement? |

Integrates empathy into clear reasoning. |

The Emotional Lens

|

Lens |

Guiding question |

Why it helps |

|---|---|---|

|

Inner emotion |

What am I feeling right now and what might that emotion be telling me? |

Connects intuition and meaning to decision-making. |

|

Shared emotion |

What are others feeling and how might that influence their behaviour? |

Builds empathic accuracy and anticipation. |

|

Emotional bias |

Which feelings might be exaggerating or distorting my judgement? |

Helps separate emotion as signal from emotion as noise. |

|

Desired emotion |

What emotional climate do I want this decision to create? |

Turns awareness into intentional emotional leadership. |

Step 3: Capture insights and contradictions

Review your notes from all lenses. Mark areas of agreement and conflict. Ask:

-

Which facts, emotions, or assumptions appear repeatedly?

-

Where do the lenses disagree?

-

What feels clear and what feels uncertain?

Why: Divergent findings signal where deeper inquiry is needed. Seeing contradiction calmly is a mark of maturity; it means you are holding complexity rather than simplifying it too soon.

Step 4: Decide and act consciously

Record your reasoning, naming which lenses most influenced you and which risks you are accepting. Communicate the decision with clarity and transparency.

Why: Documenting thought process builds accountability and learning. It also signals to others that your decision considered both logic and humanity.

Step 5: Reflect afterwards

After the outcome unfolds, revisit your notes. Ask:

-

Which lens proved most accurate?

-

What emotional or cognitive biases misled me?

-

What patterns am I noticing in how I decide?

Why: Reflection converts process into growth. Over time, reviewing decisions this way refines both instinct and discipline.

Work example

A divisional head must decide whether to merge two teams. Through the Evidence Lens, data on cost and performance are clear; the Stakeholder Lens reveals morale risk; the Values Lens warns against over-automation; the Emotional Lens uncovers personal fatigue colouring urgency. The leader pauses, consults further, and stages the merger over three phases, improving both trust and outcome.

Personal example

A leader debates whether to take a sabbatical. Using the Self, System, and Time Lenses, they weigh personal energy, organisational readiness, and timing. The Emotional Lens exposes guilt about leaving and relief at the thought of rest. Recognising both feelings as valid data, they plan a structured handover and return re-energised.

Variation: Team lens dialogue

Invite several colleagues to each take a different lens and share perspectives on the same issue. Discuss overlaps and contradictions before acting. This method spreads ownership and strengthens collective intelligence.

Why it matters: Research across decision science, behavioural economics, and emotional intelligence demonstrates that structured multi-perspective thinking improves judgement accuracy and ethical quality (Kahneman, 2011; Senge, 1990; Goleman, 2013). The inclusion of the emotional lens reflects findings from affective neuroscience showing that emotion directs attention and value weighting. Ignoring it reduces clarity; naming it enhances it.

Leaders who practise this routinely integrate cognition and empathy. They move from impulsive certainty to thoughtful confidence, capable of seeing both system and soul in every decision.

The deeper truth: Each lens is a way of listening to reality. Some listen to data, others to pattern or feeling, but all reveal part of the whole. Using many lenses teaches humility: no single frame holds the full truth.

When leaders learn to shift lenses fluidly, they begin to perceive both the seen and the felt, the measurable and the meaningful. This balance of analysis and awareness creates a deeper kind of authority — one rooted not in knowing everything, but in seeing more clearly than before.

Reality reflection log

Leaders are constantly interpreting complex situations. They must decide which information to trust, whose views to consider, and when emotion is clouding judgement. In such conditions, perception can easily drift from fact to story. Reality testing is the discipline of staying grounded in evidence while remaining aware of feelings. It helps leaders see what is actually happening, not just what they wish or fear to be true.

This practice turns that discipline into a weekly routine. By reflecting on three to five key moments or decisions each week, leaders can learn how their emotions, assumptions, and interpretations shape their view of reality. Over time, this builds accuracy, steadiness, and credibility under pressure.

Steps to take

Step 1: Choose your weekly moments

At the end of each week, select three to five moments that required discernment or involved strong emotion. These might include a meeting that shifted direction, a tough conversation, or a decision you made with limited information. Record a brief description of each.

Why: Regular review connects reflection to real leadership practice. Selecting several moments instead of one provides a fuller picture of how you process complexity. Patterns begin to emerge between confidence, stress, and accuracy.

Step 2: Capture your perception before the event

For each moment, recall what you believed or expected beforehand. What outcome did you predict? What emotions were strongest? What information seemed most reliable? Write these observations clearly and without justification.

Why: Recording the “before” view highlights how expectation and emotion shape initial interpretation. It builds awareness of how anticipation, hope, or fear influence what you notice and how you prepare.

Step 3: Record what actually happened

Describe the event as factually as possible. What was said? What decisions were made? What data or evidence emerged that you had not expected? Avoid adding judgement or commentary at this stage.

Why: Writing an objective account trains precision. It strengthens your ability to separate experience from evaluation and ensures your analysis rests on reality, not memory distortion.

Step 4: Compare perception with reality

Now place your “before” notes beside your factual record. What matched your expectations, and what did not? Which assumptions held true, and which proved inaccurate? Note any emotional reactions that changed once more information appeared.

Why: This step creates a feedback loop between belief and evidence. Seeing both together develops emotional calibration, teaching you when to trust your intuition and when to question it.

Step 5: Identify learning patterns

At the end of the month, review your weekly reflections. Look for recurring themes. When do you see most clearly? When are you prone to misread others or jump to conclusions? Note any links between emotional state and accuracy.

Why: Patterns over time reveal your personal blind spots. Recognising them allows you to make small adjustments before errors grow. This converts reflection from hindsight into foresight.

Examples in practice

Work example 1: A regional manager reviews her week and selects five moments, including a tense budget meeting. Before the meeting, she believed the operations team was defensive. Her notes show that anxiety led her to interrupt frequently. Comparing before and after reveals that her impatience, not their defensiveness, created tension. She resolves to test perceptions before acting next time.

Work example 2: A product lead records three key events, one of which was a presentation to executives. Beforehand, he expected little interest. In reflection, he notes surprise at the positive response. The log shows how low confidence distorted his expectations. Over time, he learns to distinguish preparation anxiety from actual risk.

Personal example 1: You believe a friend is avoiding you because of something you said. In your log, you record this assumption, then note that she later explained she had been travelling for work. Seeing the contrast helps you notice how self-doubt can colour relationships.

Personal example 2: You expect a family discussion about finances to become heated. After reflecting, you find that it was calm and collaborative. The exercise reveals how past experiences influenced your expectation, not current behaviour.

Variations

1. Quick FOG scan

In the moment, label statements as Fact, Opinion, or Guess. This builds instant awareness of what is known versus what is inferred.

2. Two-column reflection

Divide a page into “What was said or done” and “What I was thinking or feeling.” Capture short exchanges to reveal how emotion filters perception.

3. Paired debrief

Share your weekly reflections with a colleague or coach. Invite them to identify where emotion or bias shaped your interpretation.

Why it matters: Leaders who practise structured reflection gain clearer judgement and stronger credibility. They learn to separate emotion from evidence without dismissing either. This discipline builds resilience under uncertainty and prevents reactive decision-making. It also models intellectual honesty, encouraging teams to discuss mistakes and insights without fear. Over time, reflection transforms from a task into a mindset: one that values truth over comfort and curiosity over certainty.

The deeper truth: Reality testing is not about removing emotion. It is about integrating feeling and fact so that both inform judgement. Emotion offers signals; evidence offers stability. When leaders learn to use both, they lead from awareness rather than reaction.

Weekly reflection builds this integration through repetition. It trains attention, humility, and patience. Over time, leaders who practise it begin to see more clearly when others are clouded by stress or bias. Their authority comes not from knowing more, but from seeing more accurately. That clarity is the quiet strength behind wise leadership.

Conclusion: Seeing clearly in a world of noise

Reality testing is not a cold exercise in rationality. It is the living practice of aligning perception with truth. It begins with curiosity and matures into integrity. The six practices in this article are not analytical techniques but ways of staying honest with yourself and others. Each one strengthens a different dimension of clear sight: questioning assumptions, balancing emotion with evidence, inviting challenge, and learning from what time reveals.

This matters because in the absence of reality testing, confidence can drift into illusion. Teams lose trust when words no longer match experience. Leaders begin to defend their views rather than refine them. Over time, decisions made in isolation from fact erode credibility and morale. By contrast, when leaders ground their judgement in evidence and self-awareness, they build cultures of trust. People know that decisions are anchored in what is real, not what is convenient.

Reality testing sits at the centre of emotionally intelligent decision-making. Problem solving brings analysis. Impulse control brings discipline. Reality testing ensures both stay connected to truth. It reminds us that wisdom is not found in certainty but in the willingness to keep seeing more clearly.

The practices here are varied but connected. The Reality Reflection Log develops the habit of comparing perception with outcome. The Fact-Seeking Checklist trains the mind to pause before concluding. The Multiple-Lens Review broadens perspective beyond a single frame. The FOG Scan sharpens awareness of what is known versus what is guessed. The Assumption Challenge exposes hidden beliefs and turns them into learning. Together, these practices form a discipline of perception, a steady, humble attention to what is actually happening.

Clear seeing is not about removing emotion. It is about learning to use feeling as information and fact as anchor. Leaders who practise reality testing do not rush to judgement or hide behind data. They combine evidence with empathy, knowing that truth without compassion can harm, and compassion without truth can mislead. Over time, this balance becomes a defining mark of trustworthy leadership.

Reflective questions

-

Which of your recent decisions turned out differently from how you expected? What did that reveal about your perception at the time?

-

How do emotion and pressure influence the way you interpret events?

-

When was the last time you actively sought information that challenged your view?

-

Which colleagues or mentors help you see blind spots? How often do you ask for their perspective?

-

What signals tell you that your confidence may be drifting away from reality?

Reality testing is not about doubt but discipline. It is the daily act of choosing clarity over comfort and truth over assumption. When leaders commit to seeing clearly, they invite others into honesty, accountability, and shared understanding. In a world of noise, this is one of the rarest and most reliable forms of leadership.

Do you have any tips or advice on enhancing reality testing?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Reality Testing is a part of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and sits alongside Problem Solving and Impulse Control in the Decision Making facet.

Sources:

Bar-On, R. (1997) BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) Technical Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Bazerman, M. H. and Tenbrunsel, A. E. (2011) Blind Spots: Why We Fail to Do What’s Right and What to Do about It. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bazerman, M. H. and Moore, D. A. (2013) Judgement in Managerial Decision Making. 8th edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Stein, S. J. and Book, H. E. (2011) The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. 3rd edn. Mississauga, ON: Wiley.

Tetlock, P. E. and Gardner, D. (2015) Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction. London: Random House.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974) ‘Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases’, Science, 185(4157), pp. 1124–1131.

[…] 28, 2025 | 0 Comments Reality testing: How to see clearly and decide wisely […]

[…] Reality Testing: Reality testing anchors optimism in evidence. It protects against narrative inflation, wishful projection, and blind spots. When leaders compare their interpretation to actual data and observable facts, optimism becomes precise not sweeping, enabling confident movement without distortion. […]

[…] Previous Next […]

[…] Previous Next […]

[…] Reality Testing Loop: In a healthy leader, Reality Testing is used to navigate the terrain as it actually exists. It is the ability to see things objectively […]