We live in a culture where worth is often confused with achievement. Promotions, possessions, and recognition are treated as proof of value, while mistakes or limitations are taken as flaws to hide. Against this backdrop, self-regard can feel both radical and necessary. It is the capacity to accept and respect yourself as basically good, while also recognising where you are limited and imperfect.

Bar-On and Parker (2000) define self-regard as the ability to respect oneself while remaining aware of personal strengths and weaknesses. It is not inflated self-esteem that depends on exaggerating successes, nor is it self-criticism that reduces identity to shortcomings. Instead, self-regard is grounded confidence. Stein and Book (2011) describe it as the ability to like yourself “warts and all,” holding an accurate sense of both capability and fallibility.

The simplicity of this definition hides the challenge it represents. Many people swing between two extremes: overconfidence that conceals insecurity, or self-doubt that undermines resilience. True self-regard avoids both. It rests on balance, integrating competence with humility, pride with acceptance.

The absence of self-regard carries real costs. Some people cope by inflating their sense of importance, resisting feedback and denying mistakes. Others undervalue their contributions, hesitate to act, and withdraw when challenges arise. Both patterns erode effectiveness and relationships. By contrast, those with healthy self-regard can admit errors without shame, accept praise without arrogance, and remain steady under pressure.

Self-regard also matters beyond the individual. Leaders who value themselves are more likely to respect others, creating climates of trust and openness. Research shows that executives who score high on self-regard are more effective and lead more profitable organisations, in part because they know both their strengths and their limits (Stein and Book, 2011). When people act from self-regard, they are freed from the performance of constant self-protection. They can show up with greater authenticity and integrity.

Why self-regard matters

If self-regard is the ability to respect and value yourself as you are, the natural question is: why does it matter? Why give attention to something as ordinary as how you view yourself?

The answer lies in the way self-regard underpins almost every other aspect of emotional intelligence. It shapes how we respond under stress, how we make choices, and how we relate to others. Without it, these capacities rest on shaky ground. With it, they become steadier and more sustainable.

Resilience under pressure

Adversity tests not only skill but self-regard. When worth is fragile, setbacks lead to collapse or defensiveness. When worth is steadier, people recover more quickly. Research on self-affirmation shows that reflecting on core values buffers against stress, reduces defensive reactions, and increases openness to feedback (Sherman and Cohen, 2006). Similarly, studies of self-compassion demonstrate that treating oneself kindly after failure supports resilience and reduces rumination (Neff, 2003). Self-regard provides this resilience: the ability to face difficulty without losing respect for oneself.

Better decision making

Accurate self-appraisal strengthens judgement. People with high self-regard see both strengths and limits clearly, which makes them less prone to overconfidence and less paralysed by self-doubt. Research on core self-evaluations shows that individuals with healthier self-views set more realistic goals and persist with greater satisfaction (Judge, Bono, Erez, and Locke, 2005). By contrast, inflated self-esteem may bring pleasant feelings but is not reliably linked to performance and can even increase bias and poor choices (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, and Vohs, 2003). Self-regard brings clarity where distortion would otherwise cloud decision-making.

Stronger relationships and leadership

Relationships often falter when people project insecurity onto others. Leaders who lack self-regard may cover it with arrogance, blame-shifting, or withdrawal, all of which damage trust. Leaders with healthy self-regard can admit mistakes, invite dissent, and receive feedback without humiliation. This kind of openness creates psychological safety, the shared belief that it is safe to take interpersonal risks, which is strongly associated with better team performance (Edmondson, 1999). In The EQ Edge, Stein and Book (2011) report that senior leaders with higher self-regard are not only more effective but also lead more profitable organisations.

A foundation skill

In the EQ-i model, self-regard is not just another competency. It is a foundation. It underpins assertiveness, independence, and relationship skills. People who accept themselves can speak up without aggression, set boundaries without drama, and collaborate without losing identity. Across occupations, from engineers to executives, higher self-regard predicts success because it grounds other emotional skills in a stable sense of worth (Stein and Book, 2011).

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Self-regard reflects the ability to accept and value yourself with an accurate sense of your strengths, limitations, and inherent worth. In the EQ-i model, this composite describes how a leader holds their identity: whether they approach themselves with acceptance or judgement, grounded confidence or fragile self-esteem. When expressed in balance, self-regard supports resilience, healthy ambition, and authentic presence. When underused it leads to self-doubt, avoidance, and hesitation. When overused it drifts into inflated confidence, defensiveness, or minimising limitations. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Lacks confidence and doubts their own capability. |

Holds a grounded and realistic sense of self. |

Displays inflated self-confidence or superiority. |

|

Focuses excessively on weaknesses or mistakes. |

Acknowledges strengths and limitations without shame. |

Overemphasises strengths and downplays weaknesses. |

|

Hesitant to act, speak up, or take risks. |

Takes appropriate risks and accepts challenges. |

Takes unnecessary risks due to overestimation of ability. |

|

Struggles to internalise praise or positive feedback. |

Receives praise comfortably without arrogance. |

Rejects feedback or becomes defensive when challenged. |

|

Compares themselves negatively to others. |

Treats themselves with respect while valuing others equally. |

Minimises others’ contributions or ignores their needs. |

Balancing factors that keep self-regard accurate and grounded

Self-regard becomes most constructive when supported by emotional skills that help leaders hold a clear, realistic, and stable sense of themselves. These balancing factors prevent self-regard from collapsing into self-doubt or inflating into self-importance. They keep identity anchored in evidence, purpose, and honesty rather than emotion or comparison.

Self-actualisation: Self-actualisation provides the foundation of purpose that stabilises self-regard. Leaders who feel engaged in meaningful goals and aligned with their values develop a sense of worth that is intrinsic rather than contingent. This reduces the tendency to depend on external validation when self-regard is low or to chase achievements to sustain inflated confidence when it is overused. Purpose moderates ego by turning attention toward growth and contribution rather than appearance or perfection. When leaders draw identity from who they are becoming, not what others think, self-regard becomes steadier, quieter, and more authentic.

Problem solving: Problem solving strengthens the objectivity needed for balanced self-regard. By approaching challenges with analysis rather than emotion, leaders can evaluate their competence based on evidence. This helps correct the distortions that characterise both ends of the spectrum: underconfidence driven by fear rather than fact, and overconfidence driven by assumption rather than skill. When leaders regularly test their ideas, review outcomes, and learn from error, they cultivate a realistic appraisal of their strengths and limitations. Problem solving therefore grounds self-regard in capability rather than impression.

Reality testing: Reality testing gives self-regard its accuracy. It enables leaders to distinguish between how they feel about themselves and what is actually true. Without it, low self-regard is fuelled by harsh self-criticism and overused self-regard is fuelled by self-enhancement or denial. Strong reality testing helps leaders check assumptions, interpret feedback more accurately, and see both successes and mistakes without distortion. It invites humility without self-doubt and confidence without arrogance. When reality testing is well developed, self-regard becomes clear-eyed, evidence based, and trustworthy.

Eight practices for building self-regard

Self-regard does not grow through wishful thinking or by collecting praise from others. It develops through steady practice, ways of noticing, affirming, and balancing both strengths and limitations in daily life. These eight practices are not about inflating self-esteem. They are about grounding self-worth in evidence, honesty, and compassion.

Some practices are brief rituals, like naming a contribution after a meeting. Others invite deeper reflection, such as writing to yourself from a self-compassionate stance. Together they help you build a rhythm: noticing your value, accepting your limits, and living with a steadier sense of dignity.

The order matters less than the intention. You may begin anywhere. Over time the practices reinforce one another. Contribution naming builds into failure celebration. Strengths assessments highlight gifts, while shadow dialogues reveal their costs. Each practice helps you carry yourself with more balance and respect.

Each one is structured in the same way:

- Overview explains the purpose and spirit

- Steps guide you through the process

- Examples show it in action

- Variations suggest ways to adapt

- Why it matters grounds the practice in research and insight

Exercise 1: Gift and Shadow Dialogue

Every quality we rely on carries two sides. What others praise us for is often the very thing that, in excess, creates problems. A manager admired for decisiveness may also silence debate. A colleague known for empathy may hesitate to deliver hard truths. A parent valued for patience may avoid setting firm boundaries.

Self-regard grows when we can hold both truths together: the gift and the shadow. The danger is splitting ourselves, clinging to the gift while disowning the cost, or fixating on the shadow while forgetting the value. The Gift and Shadow Dialogue is a way of naming both sides in one breath. It helps us step out of denial and out of harsh self-criticism, into a more accurate and compassionate self-acceptance.

Psychologist Kristin Neff (2011) describes this as treating oneself with balanced awareness. Research shows that acknowledging both strengths and weaknesses reduces defensiveness and increases resilience. This practice helps you build that balance in a simple, repeatable way.

Steps

- Choose one trait you often rely on. It could be empathy, thoroughness, courage, creativity, humour.

- Name the gift. Ask: When this trait is at its best, what contribution does it make?

- Name the shadow. Ask: When this trait is overused or misapplied, what is the cost?

- Combine them. Write a single sentence that holds both truths.

- Identify the value underneath. Name the principle the gift serves.

- Design a counter-move. Create one small behaviour that keeps the gift strong while softening the shadow.

Examples

- In leadership

- Trait: Decisiveness

- Gift: Creates momentum

- Shadow: Closes off debate

- Combined: “My decisiveness moves us forward and sometimes prevents other voices from being heard.”

- Counter-move: Pause for two other perspectives before making the final call.

- In teamwork

- Trait: Empathy

- Gift: Builds trust

- Shadow: Delays hard feedback

- Combined: “My empathy builds safety and can keep me from naming what is difficult.”

- Counter-move: Pair every encouragement with one clear observation of reality.

- In personal life

- Trait: Patience

- Gift: Creates calm

- Shadow: Avoids conflict

- Combined: “My patience soothes tension and sometimes stops me setting boundaries.”

- Counter-move: Practise one short, clear “no” each week.

Variations

- Team reflection. At the start of a project, each person names one gift–shadow pair they bring. This normalises honesty and balance.

- Feedback partner. Ask a trusted peer to share when they notice your shadow emerging.

- Journaling cycle. Each week, choose a different strength and write its paired shadow. Over time, you build a balanced self-portrait.

Why it matters: The Gift and Shadow Dialogue is a practice of wholeness. It helps you stop chasing a flawless image or collapsing into self-criticism. Instead, you learn to respect the reality that every gift carries weight, and every shadow points back to something you value. Leaders who do this model humility without self-disparagement, which builds trust. Individuals who practise it develop steadier self-regard, grounded not in perfection but in acceptance.

Exercise 2: Contribution Naming

Most of us learned early to look outward for proof of worth. At school it came through marks, at work through performance reviews, and in teams through recognition from managers or peers. The danger is that self-regard becomes dependent on applause. When others notice us, we feel valuable; when they do not, we shrink.

Contribution naming reverses this habit. Instead of asking, “Did they see me?” you ask, “What did I bring that mattered?” It is a shift from external validation to internal ownership. By naming your specific contributions, you anchor self-regard in evidence you can see and respect, regardless of whether others acknowledge it.

Research on self-affirmation shows that consciously recognising our own values and contributions reduces defensiveness and increases resilience when facing setbacks (Sherman and Cohen, 2006). Over time, contribution naming creates a more grounded confidence: not inflated self-esteem, but an honest record of how you made a difference.

Steps

- Choose a fresh moment. Pick a meeting, task, or interaction from today. Keep it concrete.

- Describe it briefly. One or two sentences: “Project update call with client.”

- List contributions. Two or three specific behaviours, written as verbs. “Framed the options. Asked clarifying questions.”

- Name the value served. Link each action to a value such as clarity, inclusion, steadiness, or courage.

- Note the evidence. Identify one small sign your action had an effect.

- Say it aloud. Speaking it helps overcome the reflex to dismiss yourself.

- Close with intention. Write one behaviour you want to repeat or refine next time.

Examples

- In a team meeting

- Contribution: “I summarised the competing ideas into three clear options.”

- Value: Clarity

- Evidence: “The group quickly aligned on one choice.”

- Intention: “Next time I will pause to check if my summary feels accurate before moving forward.”

- In a client call

- Contribution: “I asked a quiet participant for their perspective.”

- Value: Inclusion

- Evidence: “They shared a concern that reshaped the decision.”

- Intention: “I will make it a practice to invite at least one overlooked voice.”

- In mentoring a colleague

- Contribution: “I listened fully before offering advice.”

- Value: Respect

- Evidence: “They said, ‘That helped me think more clearly.’”

- Intention: “I will ask two open questions before giving any guidance.”

- At home

- Contribution: “I cooked dinner after a long day so my partner could rest.”

- Value: Care

- Evidence: “They looked visibly relieved.”

- Intention: “I will keep looking for one small way to lighten their load.”

Variations

- End-of-meeting ritual. Each person names one contribution they made. This keeps ownership visible and shared.

- Weekly log. Capture three contributions each day, then review on Friday to notice patterns in your strengths.

- Peer mirror. Share your contributions with a colleague and invite them to add one more they noticed.

Why it matters: Contribution naming shifts the ground of self-worth. Instead of relying on others to affirm you, you practise affirming yourself with clarity and honesty. This builds steadier self-regard: you know what you bring, even if it is not publicly acknowledged.

It also strengthens resilience. When setbacks come, you can point to your part in the work and respect yourself for showing up. Over time, this becomes a habit of dignity, seeing yourself not as flawless, but as someone who makes a difference in ways that matter.

As Stein and Book (2011) observe, self-regard is the ability to respect yourself “warts and all.” Contribution naming makes that concrete. It is a way of saying: I am here, I acted, and what I did mattered.

Exercise 3: Reverse Feedback

Traditional feedback keeps power in the hands of others. A manager or client assesses you, while you wait to hear if you measure up. This reinforces dependence and can make self-regard fragile. When praise comes, you feel secure. When it does not, you question your worth.

Reverse feedback changes the direction. Instead of asking, “How did I perform?” you ask, “What was it like to work with me?” This question shifts the focus from evaluation to experience. You are not seeking judgment but perspective. You want to understand the impact of your presence on others.

Research shows that feedback framed around impact increases openness and learning compared to evaluative ratings (London and Smither, 2002). By practising reverse feedback, you build a balanced self-view. You honour your own contributions while also allowing others to hold up a mirror.

Steps

- Choose a recent situation. Select a meeting, project, or conversation where your presence influenced others.

- Pick two or three people. Ask colleagues, peers, or clients who experienced you directly.

- Ask the key question. Say, “What was it like to work with me in that situation?” Keep it simple.

- Listen without defence. Do not argue or explain. Clarify if needed, but let their words stand.

- Look for patterns. Note recurring themes or surprising insights across responses.

- Choose one practice. Identify a small adjustment you want to test in your next interaction.

Examples

- In a project debrief

- Response: “Working with you felt efficient, though sometimes a bit rushed.”

- Practice: “I will check in with the group once before moving on.”

- In a client meeting

- Response: “You came across calm, but also held back at times.”

- Practice: “I will share at least one perspective earlier in the conversation.”

- In a team workshop

- Response: “You created a safe space for participation, although it was hard to hear you at times.”

- Practice: “I will project my voice and check that I am clear.”

- At home

- Response: “It felt supportive that you listened, though sometimes you offered solutions too quickly.”

- Practice: “I will pause to ask if advice is wanted before giving it.”

Variations

- Feed-forward. Instead of asking about the past, ask, “What is one thing I could do differently next time that would help you?”

- Anonymous pulse. In larger groups, collect short written responses and look for themes.

- Rapid reflection. After a shared task, ask one quick version of the question: “How was it to partner with me just now?”

Why it matters: Reverse feedback strengthens self-regard by blending internal ownership with external perspective. You are not handing over your worth to others, but you are allowing their experiences to inform your growth. This builds humility without collapse and confidence without arrogance.

Leaders who practise this signal openness and earn trust. Colleagues who try it learn to see themselves through multiple lenses. Over time, reverse feedback creates a cycle of balanced self-regard: you know who you are, you listen to how you are received, and you integrate the two.

Self-regard is not about denying flaws but respecting yourself with accuracy. Reverse feedback makes that accuracy sharper, helping you accept both your gifts and your edges.

Exercise 4: Failure Celebration

Most people treat failure as something to hide. Mistakes are downplayed, explained away, or quietly buried. The cost is high: shame lingers, learning is lost, and self-regard erodes. By contrast, self-regard grows when we can name failure openly and recognise it as evidence of both effort and courage.

Failure celebration is the practice of choosing one mistake, telling the story plainly, and naming what it reveals about your growth. It reframes failure from proof of inadequacy into proof of trying.

This is not only an individual practice. Whole movements such as “Fuckup Nights” now gather people across industries to share professional failures and the lessons they carried. These events are popular precisely because they normalise what everyone experiences but rarely names. Research on growth mindset confirms that treating mistakes as opportunities for learning increases resilience and long-term success (Dweck, 2006).

Steps

- Set a rhythm. Once a week or once a month, choose a time to reflect.

- Pick one failure. Choose something specific and recent: a missed deadline, an awkward exchange, a risk that did not work.

- Tell the story plainly. Describe what happened without excuses or embellishment.

- Name the learning or courage. Ask: what quality did this failure reveal?

- Design a counter-move. Choose one small change to test next time.

- Celebrate. Acknowledge that failure is evidence of effort.

Examples

- At work

- Story: “I interrupted two colleagues in a meeting.”

- Learning: “I discovered I was anxious about being overlooked.”

- Counter-move: “I will write down my thought and wait for them to finish before speaking.”

- Celebration: “It shows I care about being heard and can now find a better way.”

- In leadership

- Story: “I misjudged how long a report would take and missed the deadline.”

- Learning: “I realised I avoid asking for help too long.”

- Counter-move: “I will set a midpoint check-in with my team.”

- Celebration: “It shows I am stretching myself and can learn to manage scope better.”

- In public speaking

- Story: “I lost my place in a presentation and froze.”

- Learning: “I rely too heavily on slides.”

- Counter-move: “I will carry a one-page outline for support.”

- Celebration: “I kept going despite embarrassment. That is resilience.”

- In personal life

- Story: “I avoided an argument at home until it grew into resentment.”

- Learning: “I confuse peace with avoidance.”

- Counter-move: “I will raise one concern each week directly.”

- Celebration: “It shows I value harmony and can learn healthier ways to hold it.”

Variations

- Team ritual. Begin meetings with “one failure, one learning.”

- Failure wall. Post sticky notes of recent mistakes and lessons.

- Story circle. Take turns sharing failures with a peer or group, modelled after movements like Fuckup Nights.

- Private reflection. Write a “failure letter” to yourself each month, naming the effort and the learning.

Why it matters: Celebrating failure reframes what it means to be human. Instead of seeing mistakes as signs of unworthiness, you learn to see them as evidence of courage. You respect yourself not because you are flawless, but because you were willing to try.

In organisations, normalising failure fosters innovation and psychological safety. In personal life, it builds resilience and compassion. And in both, it reminds us that dignity does not depend on being right. It depends on showing up honestly, learning, and continuing to grow.

Exercise 5: Strengths Assessment Integration

Self-regard is not about pretending weaknesses do not exist. It is about recognising your worth with balance. One practical way to do this is by working with your character strengths.

The VIA Survey of Character Strengths, created by Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman (2004), measures 24 universal strengths of character, organised into six broad virtues:

- Wisdom: creativity, curiosity, judgment, love of learning, perspective

- Courage: bravery, honesty, perseverance, zest

- Humanity: kindness, love, social intelligence

- Justice: fairness, leadership, teamwork

- Temperance: forgiveness, humility, prudence, self-regulation

- Transcendence: appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humour, spirituality

Everyone possesses all 24 strengths, but to varying degrees. The survey highlights your signature strengths, usually the top five, which feel natural, energising, and authentic when you use them.

Practising these strengths supports self-regard because it grounds worth in what is already strong, rather than in comparison or constant achievement. The aim is not to inflate them, but to use them with awareness, noticing both their contributions and the risks of overuse. Research shows that applying signature strengths in new ways can increase happiness and reduce depression, sometimes for months after the exercise (Seligman, Steen, Park, and Peterson, 2005).

Steps

- Take the VIA survey. Complete the free VIA Character Strengths questionnaire at viacharacter.org.

- Identify your signature strengths. Note your top five while remembering that all 24 are part of you.

- Choose one strength. Select one that feels especially relevant this week. My VIA Strengths summary may support here.

- Design one action. Identify a situation where you can apply that strength intentionally.

- Name the shadow. Each strength has an overuse risk. Write down what to watch for.

- Reflect after use. Ask: How did this strength serve me and others? Did the shadow side appear?

Examples

- Strength: Curiosity

- Action: “In tomorrow’s planning meeting, I will ask two open questions before sharing my view.”

- Shadow: Curiosity can slip into distraction.

- Reflection: “The questions opened useful discussion, but I noticed myself wanting to keep digging too long.”

- Strength: Kindness

- Action: “I will offer to review a colleague’s draft who is under time pressure.”

- Shadow: Risk of rescuing or overextending.

- Reflection: “They appreciated the support, and I also kept my own limits clear.”

- Strength: Perseverance

- Action: “I will complete one difficult report before turning to easier tasks.”

- Shadow: Can tip into stubbornness or ignoring fatigue.

- Reflection: “I finished the report, but I skipped a break. Next time I will set a timer.”

- Strength: Humour

- Action: “I will use one light comment in the client briefing to reduce tension.”

- Shadow: Too much humour can undercut seriousness.

- Reflection: “The room relaxed, but I stopped myself from overdoing it.”

Variations

- New ways challenge. Use each top strength in a way you have not tried before.

- Strengths buddy. Pair with a colleague to share how you are applying your strengths.

- Strengths spotting. Name strengths you see in others, which helps you recognise them in yourself.

Why it matters: The VIA survey provides a language for what is already good in you. Practising your signature strengths helps you respect your own worth without exaggeration. Naming the shadow side prevents arrogance, while using the gift builds confidence. Together, this balance deepens self-regard.

Self-regard is not just a general feeling of “I am enough.” It becomes specific. You can say: I am someone who brings curiosity, kindness, and perseverance. These are my gifts, and these are the risks I need to manage. That specificity turns dignity into a daily practice.

Exercise 6: Belonging Lens

Self-regard is deeply influenced by the social mirrors around us. When we feel excluded, it is easy to question our value. When we feel part of something larger, our sense of worth becomes more secure. The Belonging Lens is a practice of looking at your life through the question: Where do I belong, and how does this belonging shape how I regard myself?

Belonging does not mean fitting in at any cost. Psychologist Brené Brown (2010) distinguishes between fitting in, which requires altering yourself to be accepted, and belonging, which allows you to be seen as you are. Research shows that authentic belonging increases well-being, resilience, and motivation (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). By consciously naming the places where you feel authentic belonging, you strengthen your base of self-regard.

Steps

- List your circles. Write down the groups you are part of: family, friends, work team, community, interest groups.

- Ask the belonging question. For each circle, ask: Do I feel seen and accepted as I am, or do I feel pressure to perform or hide parts of myself?

- Note the effect. Write one line on how that belonging, or lack of it, influences your self-regard.

- Identify a strong source. Highlight one circle where you experience authentic belonging.

- Lean into it. Plan one way to strengthen your presence in that circle this week.

- Address a weak source. Choose one circle where belonging feels conditional. Decide on one experiment, such as speaking more honestly or setting a boundary.

- Reflect. Ask: What shifts when I ground my worth in authentic belonging rather than conditional fitting in?

Examples

- At work

- Belonging: “In my project team, I feel free to question ideas without judgement.”

- Effect: “It strengthens my confidence to speak up elsewhere.”

- Experiment: “I will take more initiative in that space to build on this base.”

- In family life

- Belonging: “With my siblings, I feel pressure to play the successful one.”

- Effect: “It makes me doubt my worth when I struggle.”

- Experiment: “I will share one current challenge instead of hiding it.”

- In community

- Belonging: “At my local choir, I feel accepted regardless of skill.”

- Effect: “It reminds me that joy and connection do not depend on performance.”

- Experiment: “I will attend more regularly to keep that perspective alive.”

Variations

- Mapping exercise. Draw a map of your circles, colour-coding them as high, medium, or low belonging.

- Dialogue practice. In a trusted group, share one place where you feel you truly belong and one place where you struggle.

- Micro-belonging. Notice small moments of connection in daily life, such as a genuine smile from a colleague. Record them in a journal.

Why it matters: Belonging is a stabiliser for self-regard. When you know there are places where you are accepted as you are, it is easier to face challenge, risk, and failure elsewhere. Without it, self-regard is fragile, depending on constant achievement or approval.

This practice helps you shift from asking, “Do I fit in here?” to asking, “Where am I free to be myself?” By naming and strengthening authentic belonging, you build a foundation for respecting yourself in all contexts.

As Baumeister and Leary (1995) observed, the need to belong is a fundamental human motivation. When we meet it authentically, self-regard becomes less about proving worth and more about inhabiting it.

Exercise 7: Self-Compassion Break

Self-regard falters most when we fail or feel inadequate. In those moments the inner critic can grow loud, replaying mistakes and magnifying flaws. A self-compassion break is a short, structured practice for meeting yourself with kindness instead of judgement.

Psychologist Kristin Neff (2003) describes self-compassion as three elements: mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness. Mindfulness means noticing pain without exaggeration or denial. Common humanity means remembering that imperfection is part of being human. Self-kindness means responding to yourself with the warmth you would extend to a friend. Research shows that self-compassion reduces anxiety and depression, increases resilience, and supports healthier motivation compared to self-criticism (Neff, 2011).

The self-compassion break is a simple way to practise these elements in real time, especially when mistakes or criticism trigger self-doubt.

Steps

- Pause. Notice the moment when you feel stressed, ashamed, or inadequate.

- Name the experience. Say quietly: “This is a moment of difficulty.”

- Connect to humanity. Say: “Difficulty is part of being human. Others feel this too.”

- Offer kindness. Place a hand on your chest or use a soothing gesture and say: “May I be kind to myself in this moment.”

- Choose a phrase. Repeat a statement that resonates, such as “I am allowed to learn,” or “I can treat myself gently.”

- Breathe. Take two or three slow breaths to let the words settle.

Examples

- At work

- Situation: “I made an error in a client report.”

- Break: “This is a moment of difficulty. Mistakes are part of being human. May I be kind to myself. I will correct it and learn.”

- In parenting

- Situation: “I lost patience with my child.”

- Break: “This is hard. Parents everywhere struggle with this. May I give myself patience too.”

- In leadership

- Situation: “My presentation fell flat.”

- Break: “This hurts. Leaders sometimes miss the mark. May I respond with kindness and prepare differently next time.”

- In personal growth

- Situation: “I did not follow through on my exercise plan.”

- Break: “This is disappointing. Many people struggle with consistency. May I be kind and begin again.”

Variations

- Silent practice. Use touch and breath without words.

- Written form. Write a compassionate note to yourself using the same steps.

- Group setting. Teams can close a difficult project phase with a collective self-compassion break, normalising imperfection.

Why it matters: Self-compassion is a direct antidote to the harsh inner critic that undermines self-regard. Instead of denying mistakes or drowning in them, you acknowledge difficulty, connect with shared humanity, and respond with kindness. This practice strengthens the ability to respect yourself even in failure.

Over time, self-compassion breaks shift the inner dialogue. You begin to speak to yourself as you would to someone you care about. This changes the emotional climate of your inner life and makes self-regard less conditional on success.

As Neff (2003) shows, compassion for oneself is not indulgence. It is the foundation of resilience and balanced motivation. The self-compassion break makes that foundation something you can practise in minutes, anywhere.

Exercise 8: Legacy Letter

Self-regard is strengthened when we connect our daily struggles to a larger story. A legacy letter is a practice of writing to yourself from the perspective of your future self, imagining what you hope to be remembered for and what values guided your life.

This exercise draws on the tradition of ethical wills, in which people write letters about lessons, values, and hopes to pass on to others. In the context of self-regard, the legacy letter is not for others but for you. It is a reminder that your worth is not only in what you achieve, but also in who you are becoming.

Research in positive psychology shows that reflecting on meaning and long-term values increases well-being, motivation, and resilience (Steger, 2012). By writing a legacy letter, you align self-regard with the values you most want to embody, rather than the transient successes or failures of a moment.

Steps

- Set the frame. Imagine yourself many years in the future, looking back on the life you lived.

- Choose an audience. Picture writing to a younger version of yourself, to someone you love, or simply to your present self.

- Name the values. Write about the qualities you most want to be remembered for. Examples: courage, kindness, creativity, fairness.

- Describe the impact. Write how you hope these values influenced others.

- Acknowledge imperfections. Include moments of failure or struggle as part of the legacy, showing how they shaped you.

- Close with guidance. Write one or two sentences of advice or encouragement to your present self.

Examples

- For a professional life

- “I want to be remembered as someone who combined clarity with compassion. I hope people will say I created spaces where ideas and people could grow. My failures taught me to listen more deeply and not to rush to prove myself.”

- For a personal life

- “I want my children to remember that I showed up, even when I was tired or uncertain. I hope they will know that love and humour carried us through. I want my struggles with doubt to be seen as part of what made me steady in the end.”

- For a creative life

- “I want to be remembered as someone who dared to make beauty, even when it was not perfect. I hope my work showed others that courage is not the absence of fear but the willingness to keep creating.”

Variations

- Short form. Write one page focused only on three values.

- Audio version. Record your legacy letter as a voice note to yourself.

- Annual practice. Rewrite the letter each year and notice how your hopes evolve.

Why it matters: A legacy letter pulls self-regard out of the daily scorecard and into the arc of a life. It reminds you that worth is not tied to yesterday’s mistake or tomorrow’s achievement, but to the values you live by and the presence you bring.

Writing to yourself from a future perspective helps you see your current imperfections as part of a larger story. It cultivates dignity, perspective, and steadiness. When setbacks come, you can remember: my worth is measured not in perfection but in the kind of person I am becoming.

As Steger (2012) notes, living with a sense of meaning is one of the strongest predictors of well-being. A legacy letter turns that meaning into words you can return to whenever self-regard feels shaky.

Conclusion: Living with dignity

Self-regard is not a quality you achieve once and hold forever. It is a daily practice of respecting yourself as you are, with strengths and imperfections together. The eight exercises are not techniques to inflate self-esteem. They are doorways into steadier dignity.

Each practice builds a different aspect of self-regard. The Gift and Shadow Dialogue reminds you that every quality carries both contribution and cost. Contribution Naming shifts validation from external praise to internal ownership. Reverse Feedback opens the mirror of others’ experience without surrendering your worth to their judgment. Failure Celebration reframes mistakes as evidence of courage. Strengths Assessment Integration highlights what is already strong in you, while the Belonging Lens anchors worth in authentic connection. The Self-Compassion Break interrupts the critic with kindness. And the Legacy Letter situates your value in the arc of a life rather than in a single moment.

The deeper truth is that self-regard is not about perfection. It is about honesty and acceptance. It allows you to stand before yourself without disguise, to admit mistakes without collapse, and to celebrate contributions without arrogance. From this ground you can act with greater steadiness, integrity, and presence. These exercises make the idea tangible. They help you hold yourself with respect, not because you are flawless, but because you are human.

Reflective questions

- Which of the eight practices feels most natural to begin with, and what rhythm would help it become a habit?

- Where in your life do you already experience authentic belonging, and how can you lean more deeply into that source of steadiness?

- How does your inner critic usually speak, and what words of kindness could you begin to replace it with?

- If you wrote your legacy letter today, what values would you most want to be remembered for?

Self-regard grows not in dramatic moments but in daily choices. Each time you practise it, you strengthen the ability to walk through life with dignity. And from that place, you not only respect yourself more deeply but also create conditions where others can do the same.

Do you have any tips or advice on raising or maintaining your self-regard?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

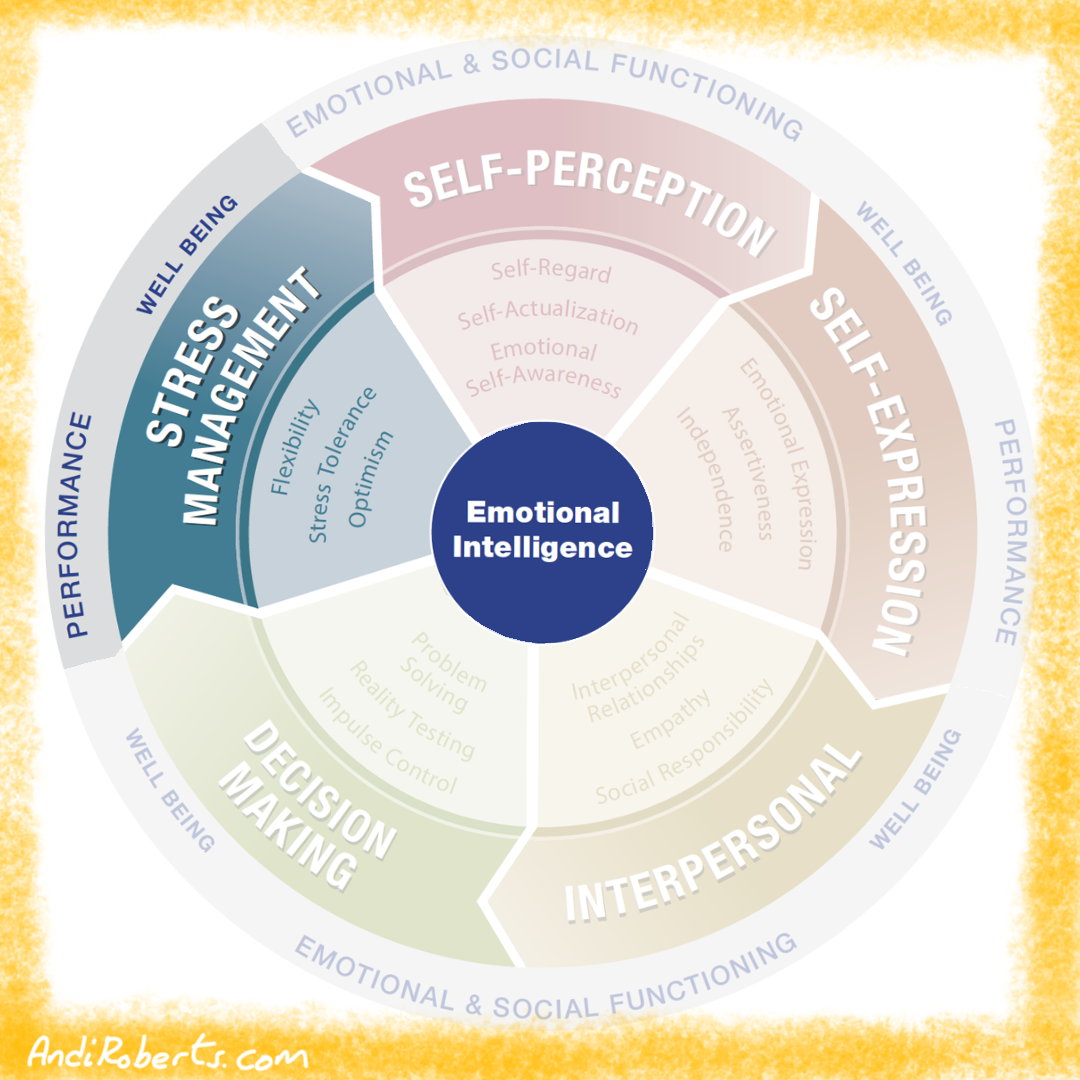

Self Regard of one of three components of Self Perception facet of the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model and also includes Self Actualization and Emotional Self Awareness.

References

Baumeister, R.F., Campbell, J.D., Krueger, J.I. and Vohs, K.D., 2003. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), pp.1–44.

Baumeister, R.F. and Leary, M.R., 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), pp.497–529.

Bar-On, R. and Parker, J.D.A., 2000. The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brown, B., 2010. The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Center City: Hazelden Publishing.

Dweck, C.S., 2006. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Edmondson, A., 1999. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp.350–383.

Judge, T.A., Bono, J.E., Erez, A. and Locke, E.A., 2005. Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), pp.257–268.

London, M. and Smither, J.W., 2002. Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Human Resource Management Review, 12(1), pp.81–100.

Neff, K.D., 2003. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), pp.223–250.

Neff, K.D., 2011. Self-compassion: The proven power of being kind to yourself. New York: HarperCollins.

Peterson, C. and Seligman, M.E.P., 2004. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M.E.P., Steen, T.A., Park, N. and Peterson, C., 2005. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), pp.410–421.

Sherman, D.K. and Cohen, G.L., 2006. The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, pp.183–242.

Steger, M.F., 2012. Making meaning in life. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), pp.381–385.

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E., 2011. The EQ edge: Emotional intelligence and your success. 3rd ed. Mississauga: Jossey-Bass.

Leave A Comment