Everyday Habits for Transforming Systems challenges the idea that meaningful change comes from heroic leaders and grand transformation programmes. Adam Kahane shows how lasting systems change grows through small, everyday actions taken by people working inside the systems they care about.

This summary presents Kahane’s seven practical habits and metaphors, offering a grounded guide for leaders, facilitators and change practitioners working in complex environments.

The book in three sentences

Adam Kahane, in his latest book Everyday Habits for Transforming Systems , invites us to engage pragmatically with the systems we are part of, starting from where we are and working with what we have, rather than attempting to design and deliver grand transformation plans. To be effective, he suggests we must learn to carve, weave, and sail: carving by getting our hands dirty and shaping change through action, weaving by bringing diverse perspectives into relationship, and sailing by working with forces beyond our control. At the heart of the book is the idea that systems shift through everyday habits and by working with the cracks they offer, noticing them and treating them as opportunities to shape, stretch, and enlarge what is possible.

My favourite three quotes

1 – “Systems are transformed generatively not by one person or team taking one big transformative action but rather by many people taking many small actions, separately and together, for many reasons.”

We often cling to the myth that systems shift only when someone steps up with a heroic plan. Adam points to something more ordinary and more hopeful. Real change usually grows from a pattern of modest moves made by many hands in many corners of the system. The work is less about forcing a breakthrough than about thousands of small gestures that nudge what is normal, expected, or taken for granted. At work, this might look like asking a different question, inviting a quieter voice, or experimenting with a small alternative rather than arguing for a grand redesign. In life it might mean taking one thoughtful step when it is available rather than waiting for perfect conditions.

Practices:

- In your next meeting, notice a small invitation you can make that could shift a conversation by one degree.

- Journal: Which tiny actions I took this week actually changed something, however slightly.

- Replace the question “What is the big move that will fix this?” with “What is one small move that I can take today?”

2 – “We transform through working with cracks”

We transform systems not by forcing change at their strongest points but by working with their cracks. These cracks are not only signs of strain or misalignment. They are also the subtle bright spots where something healthier is already taking shape. In an organisation or in civil society, there are always small practices, local experiments, friendships, or unconventional collaborations that are quietly working better than the mainstream pattern. These are early signals of a different future. The work is to notice these openings, however small, and to support them to grow. In this way, systems evolve not just through confronting what is broken but through nourishing what is already becoming.

Practices:

- In your next conversation about change, name one place where something new is already working.

- Journal: which cracks in my organisation or community feel like an emerging possibility.

- Replace “How do we fix all of this” with “How do we nurture the places where tomorrow is already visible today?”

3 – “Radical engagement refers to the day-in, day-out practice of intentionally and consciously colliding, connecting, communicating, confronting, competing, and collaborating with people from different parts and levels of the system, at the cracks, working together with them to transform that system. Radical engagement is the simple—but not easy—activity of meeting others fully.“

Radical engagement is not a slogan or a single bold act. It is the daily practice of meeting other people in the system with intention and presence. It asks us to cross boundaries, to show up in the cracks where experiences differ, and to stay in conversation even when it is uncomfortable or inconvenient. In organisations and in civil society, this means connecting not only with those who think like us but with those who sit in different roles, with different pressures, motives, or worldviews. It is about entering these encounters as a full person rather than as a defended role. Over time these repeated crossings create the connective tissue through which new patterns can take hold.

Practices:

- In your next piece of work, seek a conversation with someone whose vantage point is different to yours.

- Journal: which beliefs or habits make it harder for me to meet others as a person rather than a function?

- Replace “Who do I need to convince” with “Who do I need to genuinely meet.”

The common thread: The common thread in Adam Kahane’s three quotes is that systemic transformation is not a heroic event but an everyday discipline. Change happens through many small moves by many people, through noticing both the cracks where the old is straining and the bright spots where the new is already working, and through engaging across boundaries with genuine presence. It is practical, relational, and grounded in daily life. The work is not to wait for permission or perfect plans but to notice what is already in motion, to nurture small signals of possibility, and to meet others in the system as full people rather than fixed roles. In this way systems evolve from the inside out and from the edges in, one human interaction at a time.

Key takeaways:

Metaphors: Carving, weaving, and sailing: three ways of engaging with systems Adam Kahane offers three simple metaphors to describe what it actually takes to work inside complex systems: carving, weaving, and sailing. Together they remind us that systems change is neither purely technical nor purely relational, and never fully within our control. It is practical, social, and contingent:

Carving speaks to the necessity of getting our hands dirty. Systems do not shift through abstract designs alone. They change when people step into the material reality of the work and shape something tangible. Carving is about taking responsibility for action rather than commentary. It means making small, concrete interventions, testing ideas in practice, and learning through doing. For change practitioners, carving often looks like running a pilot, trying a new conversation structure, altering a decision rule, or naming something that has been avoided. The emphasis is not on perfection but on progress through contact with reality.

Weaving points to the relational nature of transformation. No system changes because one actor pushes harder than everyone else. Change happens when diverse people, perspectives, and interests are brought into relationship. Weaving is the work of connection. It involves building trust across boundaries, holding differences without rushing to agreement, and creating spaces where unlikely collaborations can form. This is slow, patient work, and it often happens at the edges rather than in formal structures. Through weaving, the system develops new patterns of relationships that make different outcomes possible.

Sailing acknowledges the limits of control. Systems are shaped by forces beyond any individual or group: history, culture, power, timing, and chance. Sailing means learning to work with these forces rather than fighting them. Like a sailor, the change practitioner cannot command the wind but can read it, adjust their stance, and choose when to move or wait. This requires humility, attentiveness, and adaptability. Sailing is about sensing what the system is ready for, responding to emerging openings, and accepting that progress often comes in uneven and unpredictable ways.

Taken together, carving, weaving, and sailing offer a balanced stance toward systems change. They invite us to act without arrogance, to relate without naivety, and to adapt without resignation. Instead of searching for the right plan, Kahane encourages us to develop the everyday habits that allow us to engage systems as they are and help them evolve, one thoughtful move at a time.

We are working with cracks Every system has cracks: breakdowns or bright spots where we can transform the system by small moves, nudges and probes.

The seven everyday habits of transforming systems:

1 – Acting responsibly Adam reminds us that a system keeps producing the outcomes it does because each of us continues to inhabit the roles we have chosen or accepted within it. Genuine engagement begins by noticing this. It means taking responsibility for the parts we play, and for those we have neglected or avoided. Change does not begin with blame or with heroic acts, but with a clear look at our own participation. We contribute to solutions when we can see how we also contribute to the problem, and act from that awareness.

This is not an invitation to guilt, but to care. Like elephants that tend to one another in their herd, we too are asked to take responsibility for our relatedness: to recognise our impact, our interdependence, and the choices that shape our shared life.

The book’s exercises made this tangible, especially the practice of writing from both the outside and the inside of the situation at hand. Seeing from both distances helps us notice where we stand and what we might shift.

“The first and foundational everyday habit of radical engagement, acting responsibly, involves stretching toward answers to—wrestling with—the questions, What are, today, our relationships, roles, and responsibilities in this system? Given these, what can and must we do next? With this habit as with the other six, we need to strive for progress rather than perfection.” Adam Kahane

2 – Relating in three dimensions. Adam reminds us that transforming a system calls for attention to the whole, to its parts, and to the relationships that connect those parts. Radical engagement means relating with others in all three dimensions: as participants in the system, as people with our own interests, and as kin whose lives are intertwined.

We are often most at ease in only one or two of these ways. Yet genuine transformation asks for more. It calls us to meet others, and ourselves, as whole and complex human beings, not only as the roles we play or the needs we pursue. When we practise this fuller way of relating, we begin to see the system not as something outside us, but as something we shape together.

Adam shares an appropriate Goethe quote for this habit: “Man knows himself only to the extent that he knows the world; he becomes aware of himself only within the world, and aware of the world only within himself. Every object, well contemplated, opens up a new organ within us.”

3 – Looking for what is unseen In this habit, Adam suggests that we need to see more through the eyes of others. This means stretching out and learning from others within the system. Particularly those that are not in agreement or adjacent to our views of the system. “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced”, James Baldwin.

Consider the idea of swarming the change with multiple perspectives. This taps unheard voices but also raises creativity to solving blockers to change.

Seeing others starts inside of use: We need humility, curiosity, openness, empathy and respect. Being vulnerable is critical here:

For others to open up, we can model opening up first. Many of the barriers to collaboration are inside of us and we have the capacity to reframe and reconnect with shared outcomes and dreams.

Stay alert, open and curious to what is different from your current thinking.

“The third everyday habit of radical engagement, looking for what’s unseen, involves stretching to seek out and engage with people who have positions in and perspectives on the system that are different from ours. This can be both challenging and thrilling.” Adame Kahane

4 – Working with cracks Systems are not as solid and unchangeable as they might appear and we should seek out and work with openings, in partnership with others who are doing the same. This requires us to be open to partner and engage, not only as actors and parties but also as kin.

To work with the cracks, we need to be alert to what is shifting in the system, unexpectedly or subtly and wait for openings, even if small or brief and then rapidly engage with agility.

Cracks are precursors to possibility, an opportunity for change. People close to the system see more cracks (doors) and so we need to be alert and open to seeing these. “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, say something! Do something! Get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.” John Lewis (civil rights activist/politician).

“The fourth everyday habit of radical engagement, working with cracks, involves stretching to attentively move toward and through cracks, including by engaging with imaginative and courageous others—troublemakers, entrepreneurs, innovators, artists, visionaries, young people—who are doing the same.” Adam Kahane

5 – Experimenting a way forward In order to transform a system, we have to engage with it directly, with practical problem-solving and hands-on experimentation. “There is nothing that is right or wrong until you prove it works” Sumit Champrasit (NGO founder). Progress is more important than perfection, so experiment and explore how to disrupt the status quo.

Being comfortable is an essential element with this habit as transforming systems is rarely clear or straightforward. Iterative and agile learning loops take us forward.

“The fifth everyday habit, experimenting a way forward, involves stretching to try things that might fail. We try to fail early when the stakes are low, and to fail forward by learning and improving with every attempt. This is how we can advance.” Adam Kahane

6 – Collaborate with unlike others

We need to find ways of making our differences productive by acting with those in the different spheres of the system.

Collaboration definition: To work jointly with others AND “co sooperate traitorously with the enemy”. We need to work with, through and around our differences. We need to acknowledge differences and embrace conflict: Agree on what we can and must in order to keep moving and keep learning (deliberately and patiently).

We need to work with “power” whether we agree or align or not. Create a connection to those who are different. Changing relationships enables the changing of systems. By relating, we can solve common problems and negotiate on the areas we are not aligned.

Three human drives need to be harnessed: 1) Love (the drive to reconnection), 2) Power (the drive to self-realisation), 3) Justice (the drive to right relationship).

7 – Persevering and resting Systems change is a long and winding journey and so we need adjust our course and pace as we move forward. Some systems may need several lifetimes to transform.

“Systems transformation involves working with time in contradictory ways: with urgency and patience, with beginning and ending, with pressing on and relaxing.” Adam Kahane

We need to persevere; this way we learn and become more able to contribute. This builds our own experience and capacity up.

Strategic rest is needed to combat the tensions we face and feel. Time away to take care of ourselves and close ones. Breaks allow us to refresh and get a fresh perspective. NOT TO DO lists. Beware of inattention to ourselves in the service of others.

Begin anywhere: “To contribute to transforming a system that you are part of and care about, “Begin anywhere” means: take a step beyond your habitual, familiar, comfortable position toward one where you sense an opportunity, while engaging with other people (preferably people with whom you don’t usually engage), attentively and energetically. Taking this single, small, simple-but-not-easy step will lead you to a next one and then one after that—like a baby deer, standing up, alertly looking around, taking baby steps, and thereby learning how to get around and deal with its context.” Adam Kahane

“Begin anywhere and go everywhere. There is no roadmap for transforming systems, and no one right or best place to start. You can’t know what will work, so you must simply start somewhere that you think presents an opening. Screw up your courage to take a step forward, however small, and then see where you are and what your next step will be.” Adam Kahane

Discussion guide: Adam has crafted an extensive discussion guide for readers. This in itself I found helpful and is certainly influencing my practice.

Five things you could do this week:

Five simple things I see from the book that you (or I) could do right now, even before you read the book:

1 – Map your everyday roles and their impact: Take 30 minutes to write down the roles you occupy in your current system (e.g. facilitator, manager, peer, neighbour). For each role, reflect on how your habitual actions contribute to maintaining the system as it is and where small shifts could produce different outcomes. This aligns with Kahane’s first habit of acting responsibly by recognising how we are embedded in the system.

2. Have a three-dimensional conversation: Choose one person you usually relate to mainly through roles or transactions and slow the conversation down. Stay aware of the system you are both part of and the pressures it creates, but also make space for what matters to them personally, and for the fact that your futures are intertwined, whether you agree or not. Ask a question that goes beyond task or position and invites them to speak from experience, concern, or hope. When you meet someone at the level of role, interest, and shared humanity at the same time, the system often loosens just enough for something new to enter.

3. Identify one unseen influence or perspective: In your next planning session or team meeting, deliberately ask “Who aren’t we hearing from?” and invite input (even asynchronously) from someone normally outside your usual circle. This practice helps you look for what’s unseen, expanding your understanding of the system beyond surface patterns.

4. Experiment a small way forward: Pick one tiny experiment that nudges the system differently this week. For example, test a new format for a routine meeting, try a new language in a policy draft, or spend a short block shadowing someone in a different role. Monitor results and adjust next week. This embodies experimenting a way forward, learning by doing rather than planning a perfect strategy.

5. Seek out and support a crack in the system: Deliberately find one place where the system is already responding differently (a bright spot, an informal practice that works, a group collaborating unexpectedly) and see how you can help it grow, whether by connecting actors, celebrating progress, or removing a small obstacle. This reflects the habit of working with cracks in the system.

Kahane’s seven habits encourage change agents to shift from hero-centric, big push strategies to everyday, relational, iterative actions that move systems gently over time. The emphasis is strongly on radical engagement; showing up, connecting across differences, experimenting, and noticing openings in the system where small efforts can scale into larger change.

Like all of my book summaries, this one is written to help me absorb what I have learned and to share a glimpse of the ideas with you. It is not a substitute for reading the book itself. If the content here resonates, I encourage you to seek out the full text through an independent bookstore or your local library, and let the author’s voice speak directly to you. To learn more about the author and his work visit his website or LinkedIn profile.

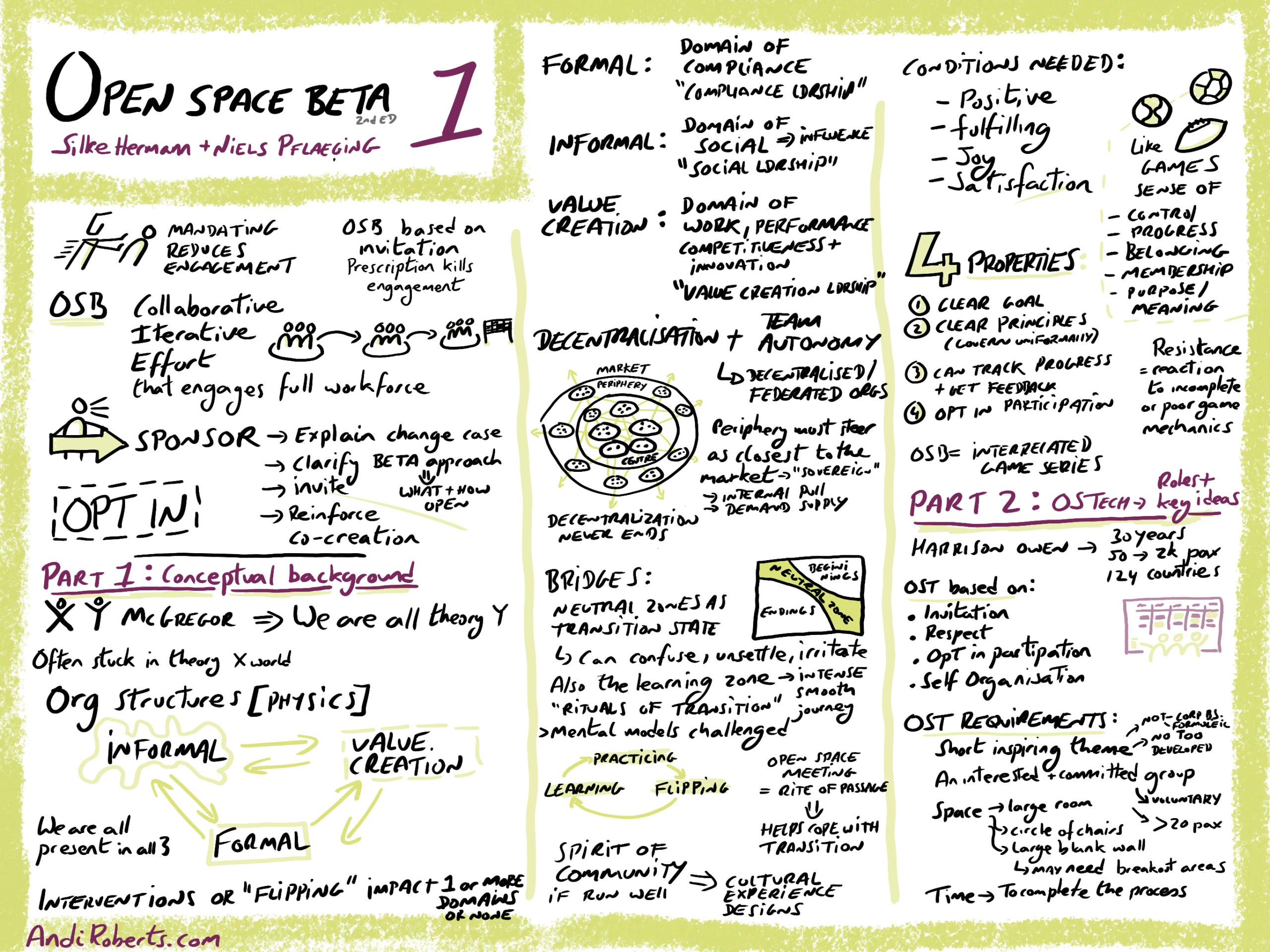

Sketchnotes:

Below are the sketchnotes that I made as I read the book. Done recently whilst on trains and planes:

Leave A Comment