We live in a culture that often prizes composure over candour. In workplaces, people are rewarded for rational analysis and calm detachment, while in families and friendships, many grow up with the message that emotions should be hidden or controlled. Against this backdrop, openly expressing feelings can feel risky or even inappropriate. The result is that many people carry emotions privately, seldom giving them voice in ways others can hear.

In the EQ-i model, emotional expression is defined as the ability to openly express one’s feelings, both verbally and non-verbally, in a way that others can understand (Stein & Book, 2011). It extends beyond simply “showing emotion” to include communicating feelings in a form that can be received and shared. Emotional expression does not mean unfiltered outbursts, nor does it mean suppressing emotions until they disappear. It is the practice of giving emotions clear, constructive voice.

The absence of expression carries significant costs. Suppressed emotions tend to surface indirectly in irritability, withdrawal, sarcasm, or stress symptoms in the body (Gross, 2002). Leaders who hide frustration may come across as cold or disengaged. Teams where joy is unexpressed can become transactional and lifeless. Relationships where sadness or anger are muted often lose intimacy and trust.

By contrast, the presence of expression creates connection. Research shows that people who communicate their emotions openly experience greater relationship satisfaction, stronger support networks, and higher well-being (King & Emmons, 1990; Srivastava et al., 2009). Naming and sharing feelings allows others to understand not only what you think, but what you care about. It transforms emotion from a private burden into shared information that deepens collaboration and trust.

Why emotional expression matters

If emotional expression is the ability to voice what we feel, the natural question is: why does it matter? Why give attention to something that many treat as optional or even dangerous?

Resilience under pressure

Unexpressed emotions tend to intensify. Research on emotional suppression shows it increases physiological stress and reduces relationship closeness (Gross & John, 2003). By contrast, openly expressing emotions, even briefly, reduces stress responses and improves coping. A manager who says, “I feel anxious about this deadline,” not only relieves internal pressure but also creates space for collective problem-solving.

Better decision-making

Emotions carry information about values, boundaries, and needs. When they remain unspoken, decisions risk being skewed by hidden drivers. A leader who feels anger but suppresses it may tolerate repeated violations of fairness. By expressing the anger with words such as, “I feel frustrated because this is not equitable,” they clarify both the value at stake and the path forward. Expression translates inner signals into shared data for wiser action.

Stronger relationships and leadership

Trust grows when people express what they feel in a way that others can understand. Leaders who name their emotions transparently with phrases such as, “I am disappointed because I value quality,” or “I am proud because this reflects our effort,” give their teams an accurate reading of the moment. This openness reduces misinterpretation, builds psychological safety, and fosters resilience in groups (Edmondson, 1999).

A foundation skill

In the EQ-i framework, emotional expression is not an optional extra but a foundational capacity. It underpins empathy, assertiveness, and healthy relationships. Without it, emotions remain invisible and misinterpreted. With it, they become a resource for clarity, trust, and connection.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Emotional expression reflects the capacity to communicate feelings openly, clearly, and appropriately through both verbal and non-verbal channels. In the EQ-i model, this composite describes how a leader shares their internal emotional experience in ways that support understanding, authenticity, and connection. The developmental question is not whether a person expresses emotion, but how proportionately and constructively they do so. When expressed in balance, emotional expression builds trust, reduces ambiguity, and strengthens relationships. When underused it results in secrecy, emotional opacity, and difficulty being understood. When overused it can overwhelm others, blur boundaries, or create discomfort. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Appears closed, guarded, or difficult to read. |

Shares feelings openly and appropriately. |

Shares too much personal detail or emotion. |

|

Struggles to articulate emotions, relying on silence or understatement. |

Expresses emotions clearly without dominating interactions. |

Makes others uncomfortable through oversharing. |

|

Seen as an enigma; others guess what they feel or think. |

Communicates feelings in ways that support understanding and trust. |

Becomes melodramatic or emotionally intense. |

|

Keeps emotions private even when expression would help collaboration. |

Balances honesty with tact in emotionally charged situations. |

Overwhelms others with frequent or unfiltered expression. |

|

Emotional needs remain invisible, creating distance or misunderstanding. |

Uses expression to strengthen connection and resolve tension. |

Blurs boundaries by expressing emotion without regard for context. |

Balancing factors that keep emotional expression healthy and proportionate

Emotional expression is strengthened and regulated by other emotional skills that help leaders communicate with clarity, respect, and attunement. These balancing factors ensure expression neither becomes suppressed nor overwhelming.

Interpersonal relationships: Interpersonal relationships provide the relational sensitivity that guides how emotions are expressed. Leaders with strong relational skills understand what others need in the moment, which helps them calibrate how much to share and how openly to communicate. This prevents emotional expression from becoming intrusive or misaligned. Healthy relationships create the psychological safety in which authentic expression can flourish without creating discomfort or imbalance.

Assertiveness: Assertiveness gives emotional expression structure. It enables leaders to state their feelings clearly, confidently, and respectfully without aggression or avoidance. Assertiveness prevents emotional expression from collapsing into passivity at the low end or emotional intensity at the high end. It ensures that feelings are communicated with boundary, timing, and intention, balancing honesty with responsibility.

Empathy: Empathy allows leaders to consider the emotional impact of their expression on others. When empathy is strong, leaders are able to read the room, gauge how their feelings may land, and adjust their communication accordingly. This prevents expression from overwhelming others or shifting conversations away from what others need. Empathy ensures emotional expression remains relational rather than self-focused, supporting connection rather than disruption.

Eight practices for building emotional expression

Like all dimensions of emotional intelligence, expression does not grow through theory alone. It is cultivated through practice, in the ordinary moments where we choose whether to speak or stay silent, to show or to hide. These eight exercises are designed as doorways into expression. Some are reflective, such as journalling and reframing. Others are embodied, like rehearsing posture and tone. Still others are relational, inviting you to practise expression in dialogue, gratitude, or storytelling.

Each exercise is structured in the same way:

-

Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

-

Steps guide you through the process.

-

Examples show it in real contexts.

-

Variations suggest ways to adapt.

-

Why it matters grounds the practice in research and lived insight.

The order matters less than the intention. You may begin anywhere. Over time, the practices reinforce one another: reframing emotion makes expression safer; embodied rehearsal makes it stronger; gratitude practice makes it more joyful. Each one helps shift emotion from private weight to shared connection.

These practices are not about dramatic displays or losing control. They are about presence. They allow you to speak feelings as signals, messages, and bridges, so that others can understand not only your thoughts but also your heart.

Exercise 1: Reflect & test cycle

For many people, emotional expression is less about “not knowing how” and more about “not daring to try.” We imagine how others might react if we show frustration, disappointment, or even joy. Our minds create vivid stories: They’ll dismiss me. They’ll get angry. They’ll think less of me. Because these predictions feel so convincing, we hold back.

The difficulty is that silence never tests the story. Each time we avoid, we reinforce the belief that expression is unsafe. Over time, emotions pile up unspoken, and relationships become more functional than authentic.

Psychological research shows that avoidance fuels anxiety, while small, structured experiments with new behaviour reduce fear and build confidence (Clark & Wells, 1995; Hofmann, 2012). The Reflect & Test Cycle brings this to life. It is a simple loop: reflect on how you handled a moment, design a new way of expressing, try it, and see what happens.

This cycle turns emotional expression into a practice of curiosity rather than risk. Instead of assuming the worst, you gather evidence about what actually happens when you speak from feeling.

Steps

-

Capture the moment

Soon after an interaction, write down the situation in detail. Who was present? What was said? Then record your automatic thought, the emotion you felt, and how you expressed it, or if you stayed silent.

Why: Capturing specifics prevents hindsight distortion. It also reveals patterns in how certain thoughts consistently block expression.

-

Spot the blocking belief

Ask yourself: What belief held me back? For example, “If I show sadness, they’ll pity me,” or “If I share frustration, I’ll look unprofessional.”

Why: Unspoken beliefs often act as gatekeepers. Naming them weakens their silent power.

-

Frame an alternative

Create a more balanced possibility. For example: “If I share calmly, they may respect my honesty,” or “If I show sadness, it may help us connect.”

Why: Alternatives loosen rigid predictions and prepare the ground for different behaviour.

-

Plan a small test

Choose one safe, specific opportunity to try the new expression. Keep it modest. Example: “Tomorrow I will say, ‘I felt concerned when we skipped that step.’”

Why: Practising in low-risk situations builds tolerance. Over time, small steps prepare you for larger ones.

-

Compare expectation with reality

Write down what you predicted would happen. Then observe what actually occurred. Did the other person listen, dismiss, respond with curiosity, or offer support?

Why: This step directly challenges distorted beliefs. Seeing the gap between expectation and reality is what reshapes confidence.

-

Reflect on learning

Ask: How did expressing change the interaction? Did I feel lighter, closer, or clearer? What did I discover about my assumptions?

Why: Reflection converts a single experiment into learning that can be applied repeatedly.

Workplace examples

-

Manager to team member: A manager believes showing disappointment will undermine authority. In a one-to-one, they say, “I felt let down when the report was late; I’d like us to plan earlier check-ins.” The employee apologises and suggests a reminder system. The manager realises that naming disappointment builds accountability rather than eroding respect.

-

Colleague in a meeting: An analyst fears that voicing frustration will sound like complaining. They say, “I felt frustrated when I couldn’t get the data on time.” The team responds by adjusting workflows. Frustration turns into constructive problem-solving.

Personal examples

-

Friendship: Someone predicts that sharing hurt will push their friend away. They say, “I felt hurt when you cancelled last minute.” The friend apologises, explains the context, and makes amends. Expression deepens the friendship instead of damaging it.

-

Family: A parent fears showing vulnerability will unsettle their teenager. They experiment by saying, “I felt sad missing your concert; I wish I had been there.” The teenager responds with empathy, showing that sadness models honesty rather than weakness.

Variations

-

Scaling expression: Start with neutral disclosures, “I’m a bit tired”, before moving to deeper emotions. Scaling helps build comfort gradually.

-

Written rehearsal: Write down what you want to say, then read it aloud to yourself. This shapes tone and clarity before the real moment.

-

Role-play practice: Practise with a coach, colleague, or friend. Say the words out loud and ask: Did my tone match the feeling? Was it clear?

-

Team check-ins: In groups, add a closing question: “What feelings were expressed today? Which stayed unspoken?” This normalises reflection on expression in collective settings.

-

Silent to spoken: If speaking feels too risky at first, write a message and share it in text form. Gradually move to saying it aloud.

Why it matters: Avoidance freezes fear. Testing unfreezes it. By comparing what we predict will happen with what actually occurs, we accumulate lived evidence that emotions can be voiced without collapse.

Studies show that behavioural testing reduces avoidance and builds resilience in social interactions (Hofmann et al., 2009). In practice, this means moving from emotion as a private burden to emotion as shared information.

The deeper truth is that growth does not come from knowing the theory of emotional expression but from lived experiments. Each test weakens silence and strengthens voice. Over time, speaking from feeling becomes not a leap of courage but a natural part of relating.

Exercise 2: Reframe the story

Many of us inherit silent rules about emotions. Anger means you are out of control. Sadness means you are weak. Fear means you are failing. Joy means you are naïve. These rules are rarely questioned, yet they quietly shape how much of our emotional life we show to others.

Stories can be rewritten. Psychologists call this reappraisal: giving an emotion a new meaning so it no longer overwhelms or shames us (Gross, 1998). Narrative therapists add that when we externalise emotions, treating them as visitors, signals, or characters, we gain freedom to speak about them without being defined by them (White & Epston, 1990).

Reframing does not erase the feeling. It shifts the ground beneath it. Anger becomes a boundary signal. Sadness becomes proof of love. Fear becomes preparation. Joy becomes alignment. When the story changes, expression becomes lighter, clearer, and less fraught.

Steps

-

Identify the emotion clearly

Write down one emotion you have recently muted. Be precise: was it resentment, loneliness, or anxiety?

Why: Specificity matters. A vague “bad” cannot be expressed usefully, but “resentful” gives a clearer signal to yourself and others.

-

Notice the inherited story

Ask: What message have I been carrying about this feeling? For example, “anger is dangerous,” “sadness is indulgent,” or “joy is childish.”

Why: Surfacing the underlying belief shows how language and culture filter expression before you even open your mouth.

-

Recast the emotion as signal

Translate the feeling into a useful frame:

-

Anger → “a boundary has been crossed.”

-

Sadness → “something I value has been lost.”

-

Fear → “I need to prepare or seek support.”

-

Joy → “this is what matters most.”

Why: When an emotion is seen as information, not threat, it becomes easier to express it in ways others can hear.

-

-

Externalise the emotion

Speak of the emotion as if it is beside you, not fused with you: “Fear is tapping me on the shoulder,” or “Sadness has taken a seat next to me.”

Why: Externalisation creates distance. Instead of being swallowed by the feeling, you describe it. That makes expression safer and clearer.

-

Express from the new frame

Share the emotion aloud, using its new meaning. For example: “I feel anger because this boundary matters to me,” or “I feel sadness because this relationship is precious.”

Why: Tone and impact shift dramatically when emotion is expressed as guidance rather than confession.

-

Reflect on the shift

After expressing, ask: How did it feel different from the old story? How did others respond? Did it open space for understanding?

Why: Reflection turns a single act of reframing into learning you can carry into future conversations.

Workplace examples

-

Team leader and anger: A leader avoids showing anger, fearing it will seem harsh. They reframe: anger signals that accountability matters. In a meeting they say, “I feel anger when deadlines are missed because it erodes trust.” The anger lands not as aggression but as clarity.

-

Employee and fear: An employee believes fear shows weakness. They reframe: fear signals preparation. Before a presentation they admit, “I’m noticing fear, and it’s reminding me to be thorough.” The openness reassures the team and reduces pressure.

Personal examples

-

Friendship and sadness: Someone hides sadness, thinking it will burden others. They reframe: sadness reveals love. They tell a friend, “I feel sadness since you moved away; it shows how important our time together has been.” The expression deepens connection.

-

Parent and joy: A parent downplays joy to appear serious. They reframe: joy signals alignment. At dinner they say, “I feel joyful hearing you share stories; it reminds me how much I value family.” Joy becomes permission, not immaturity.

Variations

-

Metaphor practice: Turn the emotion into an image: anger as a storm, sadness as quiet rain, fear as a shadow. Expressing through metaphor makes emotions vivid and less threatening.

-

Values lens: For each strong emotion, ask: “What value is this pointing to?” Anger may point to fairness, sadness to love, fear to security, joy to growth. Naming the value grounds expression in meaning.

-

Role-play reframing: Practise with a partner. Speak the old frame (“I’m weak because I’m anxious”), then the new frame (“My anxiety is reminding me to prepare”). Ask them how each version lands differently.

-

Daily reframe journal: At the end of each day, write one old story and one new story about an emotion you felt. Over time, the new story becomes easier to voice.

Why it matters: Reframing shifts emotions from liabilities to guides. Research shows that reappraising emotions reduces distress, supports resilience, and improves social connection (Gross, 2002). Narrative methods show that externalising language creates more freedom and less shame in talking about emotions (White & Epston, 1990).

The deeper truth is that emotional expression is never neutral. The words we choose either trap us in inherited beliefs or open space for connection. When we reframe the story, we release emotions from stigma and discover their purpose. Expression then becomes not an act of risk but an act of meaning.

Exercise 3: Empty chair dialogue

Unexpressed emotions often linger. A conflict with a colleague, an unresolved tension with a friend, or words left unsaid to a family member who is no longer present can weigh heavily. The emotion does not disappear; it waits, unfinished. This unfinished business can block clarity, fuel resentment, and make it harder to speak openly in new situations.

Emotion-focused therapy (Greenberg, 2011) uses the empty chair technique to surface and release these unsaid feelings. By placing an empty chair in front of you and speaking to it as though the person were present, you create space to express directly, without interruption or fear of reaction. The technique allows emotions to be processed safely and gives you practice in finding the words you could not previously speak.

Research shows that structured expression of unvoiced feelings, even in imagined settings, reduces emotional distress and strengthens readiness for real conversations (Paivio & Greenberg, 1995). This exercise transforms silence into dialogue, helping emotions move from stuck to spoken.

Steps

-

Choose the person or situation

Identify someone to whom you have unspoken feelings. It may be a colleague, a friend, a family member, or even a past version of yourself.

Why: Choosing a focus prevents vague venting and directs energy toward a relationship where expression is needed.

-

Set up the empty chair

Place a chair opposite you. Imagine the person sitting there, listening. Bring to mind their presence: their posture, expression, or even their tone.

Why: Physical presence of the chair anchors the imagination, making the dialogue more concrete and embodied.

-

Speak your unexpressed emotion

Address the person directly: “I felt angry when…” or “I felt hurt because…” Say what you could not say in the moment. Use first-person “I” language.

Why: Speaking aloud activates emotional processing differently from silent reflection or writing. It shifts the emotion into expression.

-

Switch roles

Move to the other chair and respond as if you are the other person. What might they say, even if it is difficult to hear? Speak in their voice.

Why: Role reversal builds empathy, helps you anticipate responses, and makes expression less one-sided.

-

Return and integrate

Move back to your own seat. Reflect on how it felt to voice the emotion and to imagine the response. Write down what insights or shifts emerged.

Why: Integration helps consolidate the learning so that it influences future conversations.

Workplace Examples

-

Manager and colleague: A manager feels resentment toward a colleague who took credit for their idea but has never confronted them. In the empty chair, they say, “I felt undermined when you claimed ownership of my work.” In role reversal, they hear, “I didn’t realise how it came across.” The exercise gives the manager language to use in an actual future conversation.

-

Team member and leader: An employee is anxious about expressing disappointment with their supervisor. In the chair they say, “I felt dismissed when my suggestion was ignored.” Imagining the leader’s perspective helps them rehearse a calmer, more constructive way of saying it later.

Personal Examples

-

Friendship: A person feels hurt by a friend who has drifted away. In the empty chair they say, “I miss you, and I felt abandoned when you stopped calling.” The exercise brings release even if the friend never responds.

-

Family: A son speaks to an empty chair as though his late father were present: “I wish I had told you how much your approval mattered to me.” Though the conversation cannot happen in reality, the act of speaking lifts a weight of silence.

Variations

-

Self-dialogue: Place your younger self in the empty chair. Speak to them with the emotions you carried then. Respond back from their perspective. This often surfaces compassion.

-

Team adaptation: In facilitated settings, colleagues can use paired role-play as a structured “mini empty chair” to rehearse difficult conversations.

-

Silent letter: For those who struggle to speak, write the dialogue first, then read it aloud to the chair. Reading can act as a bridge into voice.

-

Closure ritual: After the dialogue, symbolically “close” the interaction, by thanking the imagined person, standing up, or writing down one sentence of release.

Why it matters: Unspoken emotions are not neutral; they shape behaviour in subtle ways: avoidance, tension, or overcompensation. By speaking them in a safe, structured way, we give them form and reduce their hidden hold. Research on emotion-focused therapy shows that such dialogues facilitate emotional resolution and prepare people for authentic conversations (Greenberg, 2011).

The deeper truth is this: silence keeps emotions frozen. Dialogue, even imagined, begins to thaw them. The empty chair does not replace real conversation, but it rehearses and releases. In doing so, it opens space for expression to become possible again.

Exercise 4: Mindful naming out loud

Most of us move through our days naming events and tasks, but rarely naming our emotions as they happen. Instead, feelings are pushed into the background while the mind rushes to manage what’s next. Over time, this avoidance can make emotions harder to recognise and harder still to express.

Mindfulness-based approaches suggest a simple shift: notice the feeling, name it, and let it exist without judgment (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy adds that naming emotions creates distance between “I” and the feeling, making it less consuming and easier to share (Hayes et al., 1999). By saying a phrase aloud, “I notice I’m feeling anxious,” or “I notice I’m feeling joy”, we practise both awareness and expression.

This is not about fixing or analysing emotions. It is about making space. Naming emotions aloud validates them, softens avoidance, and rehearses the language we might later use with others. Over time, the act of naming builds fluency: emotions become words on the tongue, not weights carried in silence.

Steps

-

Pause to notice

In a quiet moment or even in the middle of the day, pause and check inward: What am I feeling right now?

Why: Pausing interrupts autopilot and makes space for awareness. Without noticing, expression cannot begin.

-

Name it specifically

Choose the most accurate word you can. Instead of “bad,” try “irritated,” “disappointed,” or “anxious.” Instead of “good,” try “peaceful,” “proud,” or “excited.”

Why: Specificity sharpens expression. Research shows that people with a richer emotional vocabulary regulate better and connect more effectively (Barrett, 2006).

-

Say it aloud

Speak the phrase: “I notice I’m feeling ___.” If you are alone, say it to yourself. If with a trusted person, say it directly.

Why: Speaking aloud shifts the emotion from private experience to shared reality. It begins to bridge the gap to expression in relationships.

-

Stay with it briefly

Breathe and sit with the named feeling for a few moments without trying to push it away or explain it.

Why: Allowing emotions to be present reduces the reflex to suppress or judge them. It builds tolerance for intensity.

-

Optional expression forward

If appropriate, add a sentence about what the feeling is telling you: “I notice I’m anxious because this matters to me.”

Why: Extending the phrase from naming to meaning strengthens clarity when speaking with others.

Workplace examples

-

Meeting stress: An employee feels tension before presenting. They pause, breathe, and whisper to themselves: “I notice I’m anxious.” The act of naming reduces the inner spiral and steadies their delivery.

-

Leadership check-in: A manager begins a team call by saying, “I notice I’m feeling stretched today; it may affect how quickly I respond.” The team appreciates the transparency and feels freer to share their own states.

Personal Examples

-

Parenting: A parent feels irritation rising during homework time. Instead of snapping, they quietly say, “I notice I’m frustrated.” The irritation softens and allows for calmer guidance.

-

Relationships: During a tense conversation, one partner says, “I notice I’m feeling hurt right now.” This opens the door for dialogue without blame.

Variations

-

Silent to spoken: If naming aloud feels uncomfortable at first, start by writing it down, then gradually practise saying it softly to yourself.

-

Emotion cards: Keep a small list of feeling words. When you struggle to find the right one, choose from the card and speak it aloud.

-

Team rituals: Begin group meetings with a one-sentence “I notice I feel…” round. This normalises emotional check-ins in collective settings.

-

Mindful micro-practice: Insert three “naming pauses” into your day, at the start of work, at lunch, and before bed. Each time, name your current emotion aloud.

Why it matters: Naming emotions aloud bridges two crucial skills: awareness and expression. Without naming, emotions remain diffuse and hard to communicate. With naming, they become tangible, speakable, and shareable.

Research shows that putting emotions into words, sometimes called “affect labelling”, reduces their intensity and improves regulation (Lieberman et al., 2007). Acceptance-based approaches show that this practice creates distance, so the emotion is experienced but not overwhelming (Hayes et al., 1999).

The deeper truth is that unspoken emotions often control us most. By naming them aloud, we bring them into the open where they can be acknowledged, shared, and released.

Exercise 5: Gratitude in Action

Gratitude is often described as one of the simplest emotions to feel, yet one of the hardest to fully express. Many people carry quiet appreciation for those who support, mentor, or stand by them, but the words remain unsaid. We assume they already know, or we fear it will sound awkward or sentimental. So gratitude stays hidden — and relationships miss out on the nourishment it could bring.

The cost of unexpressed gratitude is subtle but real. Teams that lack voiced appreciation become purely transactional. Families that do not exchange thanks risk drifting into routine. Friendships where gratitude is felt but never spoken can slowly lose warmth.

Psychologists note that gratitude, when expressed, strengthens bonds, increases trust, and improves resilience. Emmons and McCullough (2003) found that people who regularly practised gratitude reported higher well-being, optimism, and life satisfaction. Seligman and colleagues (2005) showed that reading a gratitude letter aloud to its recipient created immediate increases in happiness and relational closeness that lasted weeks.

The truth is that gratitude is not only an inner state. It is a form of communication. Its power lies not in being felt privately, but in being voiced, heard, and received. Gratitude in action transforms appreciation into connection.

Steps

-

Choose the person

Think of someone who has positively influenced you: a colleague, mentor, family member, or friend.

Why: Gratitude has the greatest impact when directed toward someone who matters to you personally or professionally.

-

Write the letter

Spend 10–15 minutes writing down what you appreciate. Be specific about what they did, how it affected you, and why it matters.

Why: Specificity makes gratitude more authentic and believable.

-

Deliver it aloud

Instead of sending it as an email or message, read it to them face-to-face or over video.

Why: Expressing gratitude vocally adds tone, warmth, and presence that words on a page cannot capture.

-

Notice the impact

Observe how it felt to say the words and how the other person responded. Write a short reflection afterwards.

Why: Reflection reinforces the benefits of gratitude and increases the likelihood of repeating it.

Workplace Examples

-

Leader to team: A manager writes a letter to their team, thanking them for carrying extra responsibility during a transition. Reading it aloud in a meeting energises morale and strengthens trust.

-

Colleague to peer: An employee thanks a coworker for mentoring them through a difficult project. Expressing it directly transforms the relationship into one of mutual respect and ongoing support.

Personal Examples

-

Family: A son writes to his mother: “Your patience during my teenage years shaped the way I now raise my own children.” Reading it aloud creates a moment of healing and pride.

-

Friendship: Someone thanks a friend for “always being the first to call when I go quiet.” Expressing this strengthens the bond and reassures the friend of their value.

Variations

-

Team gratitude round: End a meeting with each person naming one colleague they appreciate and why. This embeds gratitude into the culture of the group.

-

Weekly practice: Choose one person each week to thank in writing and voice. Keep a log of reflections afterwards.

-

Family ritual: Around the dinner table, each person voices gratitude for one thing about another family member. This builds connection as a shared rhythm.

-

Micro-gratitudes: Practise expressing small appreciations daily: “Thanks for explaining that so clearly,” or “I appreciate how you handled that call.” Small acts accumulate impact.

Why it matters: Gratitude left unspoken is incomplete. When voiced, it not only strengthens relationships but also reshapes the speaker. Research shows that consistent gratitude expression increases optimism, lowers stress, and improves long-term well-being (Emmons & McCullough, 2003).

The deeper truth is that gratitude, when spoken, becomes a gift twice over: the receiver feels valued, and the giver feels more connected to what matters most.

Exercise 6: Anchoring expressive confidence

Emotional expression is not only about words. It is shaped by the state of mind and body we bring into the moment. You may have the perfect sentence ready, but if you feel anxious, hesitant, or defensive, your voice will betray you. The opposite is also true: when you enter a conversation feeling strong, grounded, and resourceful, your expression carries natural clarity and ease.

Anchoring is a way to deliberately access that resourceful state. Neuro-linguistic programming (Bandler & Grinder, 1979) describes how states of confidence, enthusiasm, or clarity can be recalled by linking them to a physical gesture. Everyone has lived moments of expressive strength, times when you spoke with conviction, or expressed gratitude that landed deeply, or set a boundary with calm authority. Anchoring allows you to return to that “A game” state whenever you choose.

This is not about creating something new. It is about reminding yourself of what you already know how to do, and giving your body and mind a cue to bring it forward in the moments you need it most.

Steps

-

Recall a peak moment

Close your eyes and remember a time when you expressed yourself with power and ease. Perhaps it was a presentation that landed, a heartfelt thank you, or a difficult truth spoken with clarity. See what you saw, hear what you heard, feel what you felt.

Why: Vivid recall reactivates the state, engaging your senses so that the confidence becomes present again.

-

Immerse yourself fully

Picture yourself in that moment: standing tall, voice steady, eyes engaged. Hear the tone of your words, the energy in the room, perhaps even applause or acknowledgment. Feel the strength in your body, the posture, the breathing, the energy.

Why: The more sensory detail you access, the more strongly your nervous system “replays” the state.

-

Set the anchor

At the peak of this feeling, choose a distinct gesture, pressing thumb and forefinger together, tapping your wrist, or squeezing your palm. Hold the gesture as you stay immersed in the state.

Why: Pairing a physical action with an emotional state creates a shortcut that allows you to recall the state later.

-

Break and repeat

Open your eyes, shake out your body, or think of something neutral. Then return to the memory and repeat the anchoring gesture again. Do this several times until the link feels strong.

Why: Repetition strengthens the association, making it reliable under pressure.

-

Project into the future

Imagine a future moment where you want expressive confidence, a meeting, a performance review, or a difficult conversation. Activate the anchor and see yourself in that moment, standing tall, speaking clearly, receiving respect.

Why: Mental rehearsal with the anchor conditions your body to recall the state in real contexts.

-

Apply in practice

Before stepping into a real interaction, use the anchor to summon your state of confidence. Notice how your posture, tone, and presence shift as you enter the conversation.

Why: Anchoring brings resourceful states from memory into the present, shaping expression before words are spoken.

Workplace Examples

-

Presenting ideas: An employee recalls the confidence of leading a successful project meeting. They anchor that feeling by pressing thumb and forefinger. Before presenting to senior leadership, they trigger the anchor and speak with the same clarity.

-

Giving feedback: A manager remembers a time they gave difficult feedback with calm authority. They anchor that state and use it before their next performance review, ensuring the feedback lands without defensiveness.

Personal Examples

-

Family conversation: A parent recalls a moment of patience and warmth with their child. They anchor that tone and activate it before discussing a sensitive issue.

-

Friendship: Someone remembers the ease of expressing gratitude to a close friend. They anchor that state and use it before sharing something vulnerable with another friend.

Variations

-

Multiple anchors: Create anchors for different states: calmness, joy, determination. Use the one most helpful for the situation.

-

Sensory triggers: Pair the anchor with music, a scent, or a visual cue that reinforces the state.

-

Environmental anchors: Associate a place: a favourite chair, a walking path, or a meeting room, with confident expression. Being in that place activates the memory.

-

Team version: In a group, invite members to recall a time of strong expression, set an anchor, and share the experience. This normalises the idea that expressive power is already present in everyone.

Why it matters: Expression flows best when grounded in confidence. Anchoring is a practical way to bring past strengths into present challenges. Research on memory and state-dependent learning shows that emotional states can be reactivated by cues (Tulving & Thomson, 1973). Anchoring makes those cues intentional and usable.

The deeper truth is this: you already have lived moments of expressive power. Anchoring ensures they are not left behind as memories but brought forward as resources, available whenever you need to speak with clarity, conviction, and ease.

Exercise 7: Embodied expression rehearsal

When we think of emotional expression, we often picture words. We search for the right phrase, rehearse sentences in our head, and hope our message will land. But expression is never just verbal. The body is always part of the message. A slouched posture can drain conviction from carefully chosen words. A tense jaw can make reassurance sound brittle. A flat tone can make gratitude feel hollow.

Psychologists estimate that much of emotional meaning is communicated non-verbally (Mehrabian, 1971). Research on embodied emotion also shows that the way we hold our body feeds back into how we feel: posture, movement, and breath shape the very emotions we experience (Niedenthal, 2007). If body and words align, expression feels authentic and powerful. If they clash, others sense the gap immediately.

Drama therapy and somatic psychology use rehearsal to strengthen this alignment. By “trying on” emotions through posture, gesture, breath, and tone, we practise the physical vocabulary of expression before stepping into real conversations. This builds both authenticity and range: we discover that we can express sadness without collapse, anger without aggression, joy without awkwardness.

Embodied rehearsal is not performance. It is practice in congruence. It trains us to let the body support the message, so that emotions are not just stated but lived in communication.

Steps

-

Choose the focus emotion

Identify one emotion you often find hard to express. Perhaps anger feels unsafe, sadness feels weak, or joy feels embarrassing. Write it down.

Why: Choosing a specific emotion gives rehearsal direction and allows you to focus on an area of growth.

-

Find its posture

Stand or sit and let your body shape itself into that emotion. For anger, you might stand tall, shoulders square, fists clenched. For sadness, you might let your shoulders slump and gaze drop. For joy, you might open the chest and lift the chin.

Why: Emotions live in the body before they reach words. Posture is often the most direct doorway into feeling.

-

Add breath and movement

Notice how this emotion breathes. Is it shallow, fast, deep, or slow? Try moving as the emotion might move — pacing, rocking, bouncing.

Why: Breath and movement make the emotion dynamic, not static. They help you inhabit it more vividly.

-

Layer in vocal tone

Speak a neutral phrase like “This matters to me” or “I am here” while in the posture and breath of the emotion. Match the tone to the feeling: firm for anger, soft for sadness, bright for joy.

Why: Voice is the bridge between inner experience and outer communication. It carries the emotional charge that words alone cannot.

-

Exaggerate, then soften

Push the expression beyond what feels natural: louder, softer, bigger, smaller. Then bring it back to a moderate level.

Why: Exaggeration builds tolerance for intensity and shows you that you can modulate expression rather than avoid it.

-

Integrate with real words

Practise speaking an actual sentence you might want to use, “I felt hurt when…” or “I’m proud of this work”, while maintaining the posture, breath, and tone.

Why: Integration ensures the body supports the meaning, making your expression congruent and believable.

-

Reflect on congruence

Afterwards, ask: Did my body, voice, and words align? How did it feel to speak this way? What shifted compared to my usual expression?

Why: Reflection consolidates learning and prepares you to apply it spontaneously in life.

Workplace Examples

-

Asserting a boundary: An employee rehearses saying no with squared shoulders, steady breathing, and a firm but respectful tone: “I can’t take this on right now.” When spoken in a meeting, the boundary lands clearly without defensiveness.

-

Recognising others: A leader practises expressing gratitude with open posture, leaning forward slightly, and warm tone. Later, when thanking a team member, the appreciation feels authentic and energises the room.

Personal Examples

-

Parenting: A parent who hides sadness practises letting shoulders drop and speaking softly: “I feel sad I missed your event.” When shared at home, the sadness feels real and is met with empathy.

-

Friendship: Someone rehearses expressing joy with open arms, upright posture, and smiling voice: “I’m so happy for you.” When said to a friend, the joy feels unforced and contagious.

Variations

-

Mirror rehearsal: Practise in front of a mirror to observe whether your face, posture, and voice support or undercut your words.

-

Partner feedback: Practise with a trusted friend or coach. Express an emotion and ask: “Did my body and tone match the words?”

-

Emotion circuits: Cycle through anger, sadness, joy, and fear, embodying each fully, then speaking a phrase. This broadens your expressive vocabulary.

-

Group exercise: In team workshops, members can rehearse expressing appreciation, frustration, or excitement through body and words, then reflect together.

Why it matters: When emotions are misaligned with the body, others sense hesitation, inauthenticity, or even contradiction. When words, tone, and posture align, expression feels natural, trustworthy, and impactful.

Research on embodied cognition shows that posture and movement influence both internal emotion and external communication (Niedenthal, 2007). Practising embodied expression strengthens authenticity and builds confidence to voice emotions clearly in real interactions.

The deeper truth is this: emotions are not abstract states. They are lived through the body. Practising them physically ensures that when the moment comes to speak, your body and words move together, not against each other.

Exercise 8: Narrative externalisation

When strong emotions arise, many of us fuse with them. We say, I am angry. I am anxious. I am sad. The emotion becomes an identity. This makes expression harder, instead of sharing how we feel, we fear being judged as the feeling itself: If I am anger, then I am dangerous. If I am sadness, then I am weak.

Narrative therapy offers a different approach: externalisation (White & Epston, 1990). Instead of seeing emotions as who we are, we treat them as visitors, signals, or characters that come and go. “Anger is visiting me right now.” “Sadness is sitting beside me.” “Anxiety is knocking at the door.” By naming emotions this way, we create space. We are not swallowed by the feeling; we are in relationship with it.

This shift matters for expression. When emotions are externalised, it becomes easier to speak about them. You can describe what anger wants, what sadness is telling you, what joy is asking you to celebrate. The listener hears not a confession of identity but a story about a companion emotion. Expression becomes vivid, imaginative, and less threatening for speaker and listener alike.

Steps

-

Notice the emotion

Begin with awareness. Ask: What am I feeling right now? Anger, fear, sadness, joy, or something more nuanced like shame, relief, or anticipation?

Why: Specific naming creates the foundation for externalising.

-

Give the emotion a character

Imagine the emotion as if it were a visitor, animal, weather pattern, or character. Anger might be a storm. Sadness might be a quiet guest in the corner. Joy might be a firework.

Why: Metaphor makes emotion tangible, easier to describe, and less fused with your identity.

-

Speak about it as separate

Use phrases like: “Anger showed up when my ideas were ignored.” “Sadness is sitting with me today.” “Anxiety is knocking, asking me to prepare.”

Why: Separation reduces shame and helps you express the emotion without being defined by it.

-

Explore its message

Ask: What is this visitor trying to tell me? What value is it pointing to? For example, anger may signal fairness, sadness may reveal love, fear may ask for safety.

Why: Emotions, seen as messengers, become information rather than threats.

-

Express it to another

Share your externalised description with a trusted person: “Sadness is visiting because I miss the closeness we had.” Notice how it feels different from saying “I am sad.”

Why: Sharing from an externalised frame makes the emotion easier to hear, often sparking curiosity instead of defensiveness.

-

Reflect on the effect

Afterwards, ask: Did speaking this way make the emotion easier to express? Did it change how the other person responded?

Why: Reflection builds awareness of how language shapes expression and reception.

Workplace examples

-

Team frustration: A project manager says, “Frustration visited me in that meeting because timelines kept slipping.” Colleagues engage the metaphor, asking, “What is frustration asking of us?” This creates dialogue rather than blame.

-

Leadership transparency: A leader shares, “Anxiety is hovering as we enter this merger; it’s reminding me to prepare carefully.” The team feels reassured, not alarmed, by the honesty.

Personal examples

-

Friendship: Someone says, “Loneliness is knocking since you moved away.” The friend responds with empathy and an invitation to reconnect. The metaphor softens the heaviness of the feeling.

-

Parenting: A parent tells their child, “Joy is dancing in me when I hear you play music.” The expression lands playfully, strengthening connection.

Variations

-

Art-based externalisation: Draw the emotion as a character or scene. Share the drawing with someone as a way of expressing the feeling.

-

Dialogue with the visitor: Write a short dialogue: “Anger, why are you here?” “To remind you that fairness matters.” Speaking it aloud deepens the sense of separation and meaning.

-

Storytelling circles: In teams or families, invite members to share emotions as visitors: “Today, excitement dropped by,” “Stress came knocking.” This normalises expression without self-judgment.

-

Naming ritual: At the start or end of the day, name one “visitor emotion” aloud: “Today, hope joined me,” or “Exhaustion tagged along.” A simple rhythm that keeps emotions acknowledged.

Why it matters: Externalisation reshapes the relationship between self and feeling. Instead of being defined by an emotion, you stand beside it and give it voice. Research in narrative therapy shows that externalising reduces stigma, supports self-compassion, and opens space for new meaning (White & Epston, 1990).

The deeper truth is this: emotions are not your identity. They are companions that visit, bringing messages about what matters. By speaking of them as visitors, you free yourself from shame and give others an easier way to listen. Emotional expression becomes not an admission of weakness but a story about the values and needs that guide your life.

Conclusion: Speaking emotions into life

Emotional expression is not a one-time skill to master. It is a daily practice of giving voice to what matters, in ways that others can hear and understand. The eight exercises in this article are not techniques to perform but doorways into presence. Each one offers a way to bring feelings out of the shadows of silence and into the shared space of dialogue and connection.

This matters because emotions are not side notes to life. They are signals, teachers, and bridges. When suppressed, they become distortions that surface in stress, withdrawal, or conflict. When expressed, they become pathways to trust, resilience, and understanding. To practise emotional expression is to choose openness over hiding, clarity over confusion, and connection over distance.

The practices outlined here are deliberately varied. A thought–feeling log helps you see the patterns beneath silence. Reframing emotion as resource turns fear into information. Embodied rehearsal teaches the body to align with words. Anchoring allows you to summon confidence at will. Gratitude in action transforms appreciation into connection. Narrative externalisation gives difficult emotions a voice without shame. Together, these practices form a cycle of expression: noticing, embodying, reframing, voicing, and sharing.

Emotional expression is not about dramatic displays or constant openness. It is about choice. It gives you the ability to decide when and how to voice what you feel, with honesty and clarity. Over time, this practice strengthens not only relationships but also self-trust. You come to know that you can face your emotions, name them, and speak them into life.

Reflective questions

-

Which of the eight practices feels most natural for you to try, and which feels most stretching? What does that reveal?

-

In what settings do you most often mute your emotions, and what would change if you voiced them more directly?

-

Which emotion in your life most needs a healthier expression: anger, sadness, joy, or fear? What practice might open that doorway?

-

How might your relationships shift if you spoke feelings not only in moments of tension but also in moments of gratitude and joy?

Emotional expression is not about becoming someone else. It is about becoming more fully yourself. By practising expression, you create the possibility of relationships rooted in trust and a life lived with greater clarity and connection.

Do you have any tips or advice on practising emotional expression?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

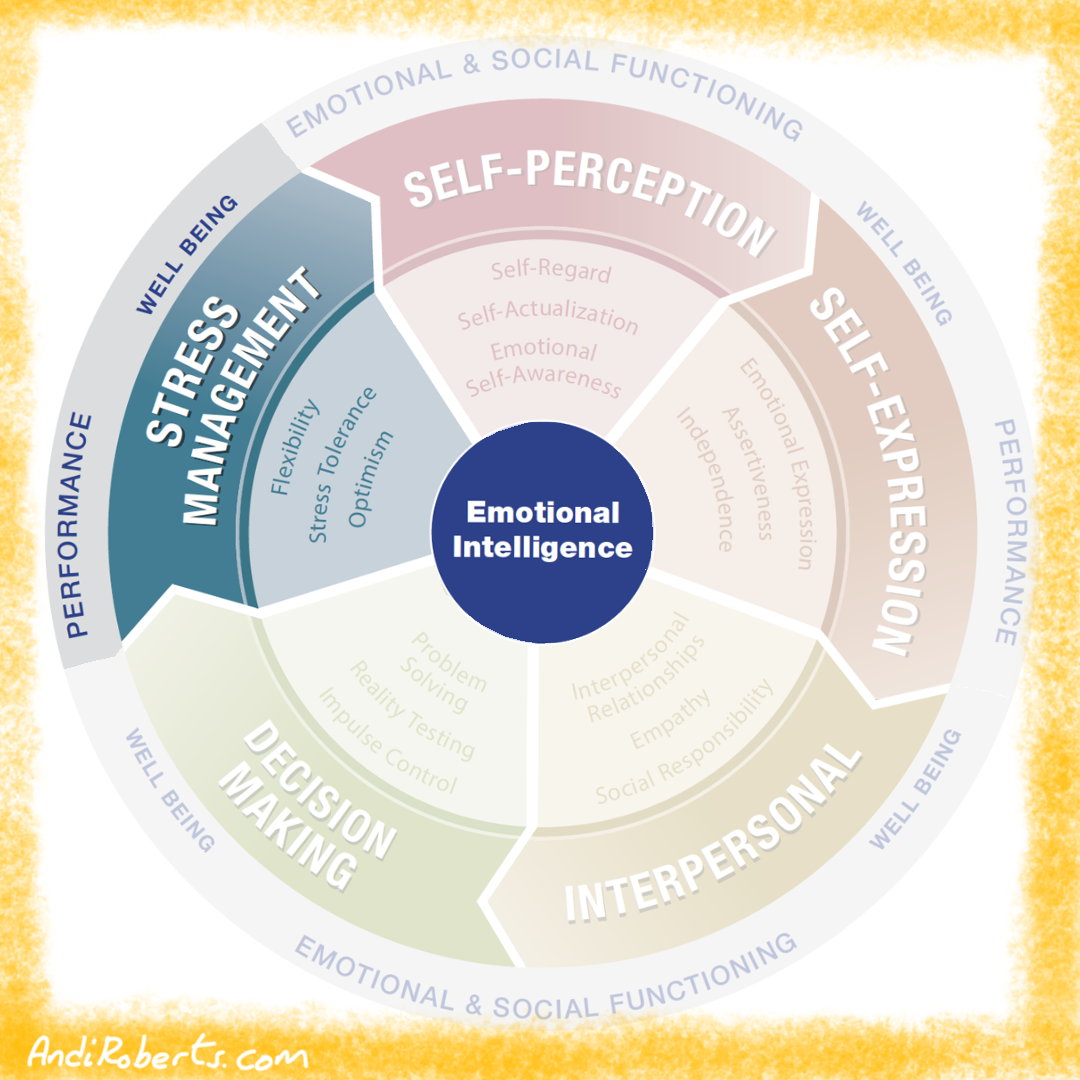

Emotional Expression is one of three components of the Self Expression facet from the MHS EQ-i Emotional Intelligence model, along with Independence and Assertiveness.

Sources

Bandler, R. and Grinder, J. (1979) Frogs into princes: Neuro linguistic programming. Moab, UT: Real People Press.

Barrett, L.F. (2006) ‘Solving the emotion paradox: Categorization and the experience of emotion’, Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(1), pp. 20–46.

Barrett, L.F. (2017) How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Edmondson, A. (1999) ‘Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp. 350–383.

Ellis, A. (1955) ‘New approaches to psychotherapy techniques’, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 11(3), pp. 207–260.

Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam.

Greenberg, L.S. (2002) Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Gross, J.J. (2002) ‘Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences’, Psychophysiology, 39(3), pp. 281–291.

Gross, J.J. and John, O.P. (2003) ‘Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), pp. 348–362.

Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D. and Wilson, K.G. (1999) Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990) Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte.

King, L.A. and Emmons, R.A. (1990) ‘Conflict over emotional expression: Psychological and physical correlates’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), pp. 864–877.

Lieberman, M.D., Eisenberger, N.I., Crockett, M.J., Tom, S.M., Pfeifer, J.H. and Way, B.M. (2007) ‘Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli’, Psychological Science, 18(5), pp. 421–428.

Mehrabian, A. (1971) Silent messages. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Niedenthal, P.M. (2007) ‘Embodying emotion’, Science, 316(5827), pp. 1002–1005.

Seligman, M.E.P. (2002) Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M.E.P. and Schulman, P. (1986) ‘Explanatory style as a predictor of productivity and quitting among life insurance sales agents’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), pp. 832–838.

Srivastava, S., Tamir, M., McGonigal, K.M., John, O.P. and Gross, J.J. (2009) ‘The social costs of emotional suppression: A prospective study of the transition to college’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), pp. 883–897.

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E. (2011) The EQ edge: Emotional intelligence and your success. 3rd edn. Mississauga, ON: Wiley.

Tulving, E. and Thomson, D.M. (1973) ‘Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory’, Psychological Review, 80(5), pp. 352–373.

White, M. and Epston, D. (1990) Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: W.W. Norton.

Leave A Comment