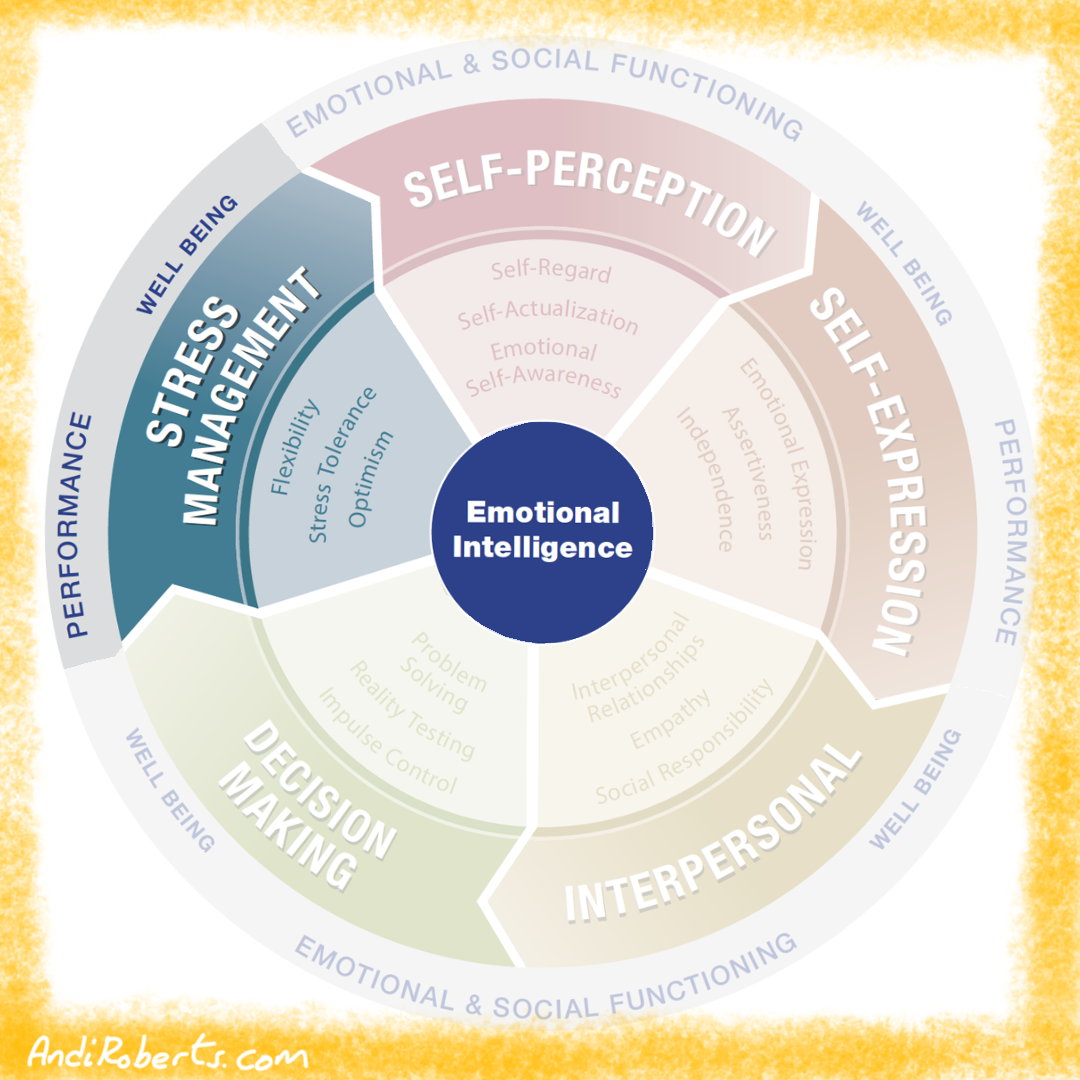

Modern work often rewards individual success, visibility, and competition. Yet personal achievement alone cannot sustain belonging or meaning. Human beings flourish when they contribute to something larger than themselves, when their actions serve both their own growth and the wellbeing of others. Social responsibility is the emotional intelligence that makes this possible. It is the ability to act with care, fairness, and cooperation, ensuring that what benefits the self also strengthens the whole.

In the EQ-i model, social responsibility is defined as the ability to demonstrate oneself as a cooperative, contributing, and constructive member of one’s social group; to show concern for the welfare of others; and to act in ways that benefit one’s community (Stein and Book, 2006). It represents emotional intelligence turned outward. Empathy becomes contribution, and values become practice. This capacity is not about charity or compliance. It is about the steady discipline of acting with integrity and regard for others, even when no one is watching.

When social responsibility is absent, the costs surface slowly. Teams begin to fracture into silos. Short-term advantage replaces shared purpose. People become cautious rather than caring, guarding time and information rather than sharing them. At the other extreme, those who give endlessly without reciprocity burn out, carrying the emotional weight for everyone else. In both cases, cooperation collapses. The invisible threads of trust that hold communities together start to fray.

Healthy social responsibility, by contrast, creates balance. It grounds fairness and compassion in daily behaviour. It makes generosity sustainable. When individuals contribute consciously to their group’s welfare, they strengthen their own resilience and purpose. When organisations act responsibly toward their people and communities, they earn not just performance but loyalty. Responsibility, at its best, is not a burden but a source of energy. It tells us that we belong to one another.

Why social responsibility matters

It anchors ethics in everyday behaviour

Values mean little until they are lived. Social responsibility turns ethical principles into visible habits: how feedback is given, how workload is shared, and how decisions affect others. This translation from belief to practice is what gives values their credibility.

It sustains cooperation and fairness

True collaboration depends on mutual care. When people act responsibly toward one another, they make interdependence safe. They share credit, support others under pressure, and distribute effort more evenly. This balance prevents burnout and resentment while deepening trust.

It builds belonging through contribution

Belonging is not created by slogans or social events but by participation that matters. When people contribute in ways that visibly improve the group, they feel valued and connected. Responsibility transforms “being part of” into “making a difference to.”

It expands foresight and perspective

Acting responsibly requires awareness of systems and consequences. It invites reflection on who benefits, who bears the cost, and what values are being served. This awareness broadens perspective and strengthens ethical judgment under pressure.

A foundation of emotional maturity

In the EQ-i framework, social responsibility grows alongside empathy and interpersonal relationships, but it carries a distinct orientation. It moves from understanding others’ feelings to supporting their wellbeing. It connects emotional awareness with collective action. Without it, empathy risks remaining internal and unexpressed. With it, empathy becomes service.

Social responsibility begins with the nearest circle and expands outward. It is present in the fairness of a decision, the generosity of a gesture, and the courage to speak for those who cannot. Each small act strengthens the culture around it. Over time, these everyday contributions form the ethical architecture of trust.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Social responsibility reflects the capacity to contribute meaningfully to the welfare of others, to participate in group life, and to act with a sense of shared obligation. In the EQ-i model, this composite describes how a leader balances personal priorities with collective needs, demonstrates care for others, and engages responsibly in teams and communities. The developmental question is not simply whether a leader helps, cooperates, or volunteers, but how proportionately they offer support and participation. When expressed in balance, this capability strengthens trust, cohesion, and consistent contribution. When underused it results in disengagement, reluctance to commit, and self focus. When overused it can lead to over-functioning, taking on too much, or prioritising harmony over integrity. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Unwilling to be involved in the group or team. |

Cooperative and dependable in group settings. |

Takes on more than is healthy or sustainable. |

|

Hesitant to commit to group activities. |

Contributes time, care, and effort to shared goals. |

Makes popular choices rather than principled choices. |

|

Focuses mainly on own tasks and priorities. |

Acts responsibly and follows through on commitments. |

Becomes rigid around rules, norms, or expectations. |

|

Difficulty following through on collective responsibilities. |

Feels genuine concern for others’ welfare. |

Allows others to lean too heavily on them or exploits their reliability. |

|

Limited interest in group success or cohesion. |

Balances personal and group needs effectively. |

Absorbs others’ work, problems, or emotional burdens. |

|

Avoids responsibility beyond own role. |

Helps create a sense of fairness and mutual support. |

Over identifies with being the helper or rescuer. |

Balancing factors that keep social responsibility healthy and sustainable

In the EQ-i framework, social responsibility is strengthened by other emotional capabilities that prevent helpfulness from becoming over-functioning, and care from becoming self-sacrifice. These balancing factors ensure that contribution remains purposeful, reciprocal, and grounded rather than driven by guilt, pressure, or dependency.

Self actualisation: Self actualisation provides a sense of personal purpose that keeps social responsibility anchored and authentic. Leaders with strong self actualisation contribute from fulfilment rather than from a need for approval or significance. They give because it aligns with their values, not because they feel compelled or responsible for everyone’s wellbeing. This prevents overuse by ensuring that contribution does not replace personal meaning, identity, or growth.

Interpersonal relationships: Healthy interpersonal relationships ensure that social responsibility remains mutual rather than one-directional. When leaders cultivate strong relational connections, giving and support flow both ways. They develop the ability to ask for support, set shared expectations, and honour boundaries within relationships. Strong interpersonal relationships prevent social responsibility from sliding into rescuing, people pleasing, or over-accommodating others at personal cost.

Empathy: Empathy enables leaders to understand what others truly need rather than assuming or over-identifying. When empathy is well balanced, leaders support others in ways that are helpful but not intrusive, considerate but not enabling. It allows them to distinguish between appropriate support and over-responsibility. Empathy also protects against burnout by ensuring that care is grounded in accurate perception rather than emotional over-extension, guilt, or taking on problems that belong elsewhere.

Eight practices for strengthening social responsibility

Social responsibility grows not from obligation but from intention. It is the steady habit of contributing to something larger than oneself, whether that is a team, a community, or the relationships we inhabit every day. In the EQ-i model, social responsibility is less about heroic acts and more about consistent, grounded participation in the wellbeing of others. The eight exercises that follow offer practical ways to deepen this sense of shared contribution. Some cultivate inner alignment, such as reconnecting with personal values or clarifying motives for helping. Others focus on behaviour, such as strengthening dependability or practising healthy boundaries. Together, they form a toolkit for responsible, sustainable, and meaningful engagement.

Each exercise follows the same structure:

Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

Steps guide you through the process.

Examples demonstrate application in real contexts.

Variations offer ways to adapt.

Why it matters grounds the practice in research and insight.

These practices are not about self sacrifice or people pleasing. They help leaders contribute without over extending, engage without losing themselves, and support others without becoming responsible for what is not theirs. Social responsibility is, at its heart, a balance between personal integrity and collective care. It reminds us that contribution is most powerful when it is intentional, sustainable, and aligned with our values, and that the quality of what we give is shaped by the clarity of why we give it.

Values to action audit

Most people can name a handful of values they care about. Far fewer can point to the daily choices that make those values visible. Social responsibility is not a posture or a slogan. It is the quiet consistency between what we say matters and what we actually do when nobody is watching. The gap between belief and behaviour is where trust is either built or lost.

A Values to Action Audit closes that gap. It invites you to translate ideals into observable behaviours that benefit others. The goal is not perfection. The goal is integrity. When your actions reflect your principles, people experience you as reliable and fair. Teams can relax. Communities can trust your word. Over time, consistency becomes contribution because it removes the friction of second guessing your intentions.

This exercise is deliberately simple. You will name your top values, identify the behaviours that express them, and then examine your week for alignment and drift. The outcome is clarity about where you are already contributing and where a small shift could serve the common good more fully.

Steps

1) Name your top values

Choose three to five values that matter most to you. Examples include fairness, courage, stewardship, respect, inclusion, honesty, and service. Write them in your own words so they feel alive rather than abstract. If you work within an organisation, consider which stated values you personally commit to uphold. Keep the list short enough to remember.

Why: Focus creates traction. A long list diffuses attention and invites rationalisation. A short list invites accountability because you can hold it in mind when you decide and act.

2) Define visible behaviours for each value

For each value, list two or three concrete behaviours that would make it visible to others. For fairness, you might rotate opportunities and share credit. For inclusion, you might structure meetings so quieter voices have time to speak. For stewardship, you might protect people’s time and use resources carefully. Make these behaviours specific enough that someone else could observe them without guessing.

Why: Values only guide action when they are translated into verbs. Clarity about what the value looks like prevents drift and turns good intentions into habits.

3) Scan your last seven days for alignment

Look back over the past week. Where did you act in line with your stated behaviours, and where did you fall short? Write one example of alignment and one example of drift for each value. Be precise about moments, not general impressions. Note any patterns that appear, such as time pressure, emotional triggers, or particular contexts that make alignment harder.

Why: Recent and concrete review prevents wishful thinking. Patterns reveal the conditions under which values are most at risk, which allows you to plan supports rather than rely on willpower.

4) Choose one micro commitment for the next seven days

Select one value and one behaviour to practise deliberately this week. Keep it small and testable. For example, invite two additional voices in every meeting you chair, or acknowledge one unseen contribution each day. Schedule reminders where they matter, such as in your calendar holds or meeting agendas.

Why: Change sticks when it is specific and repeatable. A micro commitment turns reflection into practice and allows you to gather evidence that the behaviour is possible in real conditions.

5) Create a simple accountability loop

Tell one person what you are practising and ask them to notice it. Invite quick feedback at the end of the week. If appropriate, share what you learned with your team and name the next behaviour you will work on. Keep records in a short log so you can see progress across weeks.

Why: Accountability transforms preference into standard. When others know what you stand for and what you are working on, trust grows because your values become predictable in public.

Workplace examples

Hiring fairness: A manager lists fairness as a core value. Visible behaviours include diverse shortlists and structured interviews. After the audit, she notices informal referrals are crowding out other candidates. She adds a blind screen step and debriefs outcomes with the hiring panel. The team experiences the process as more transparent and credible.

Inclusion in meetings: A product lead commits to inclusion. He defines one behaviour as inviting two quiet contributors before closing any discussion. After a week of practice he notices better ideas surface and decisions face fewer objections later, because more perspectives were integrated early.

Personal examples

Family stewardship: Someone values stewardship at home. They define it as planning shared resources with care, including time. After noticing frequent last minute schedule changes, they introduce a Sunday 15 minute planning check in. Stress lowers and commitments become more reliable.

Community service: A neighbour values service. She defines one behaviour as offering practical help to an elderly resident once a month. After three months the small rhythm becomes a natural part of her routine and inspires two others on the street to join.

Variations

-

Team alignment lab: As a team, choose one shared value and co define three behaviours. Run a two week experiment and debrief what helped and what hindered alignment.

-

Red team your values: Ask a trusted colleague to challenge where your actions may contradict your stated values. Treat it as data, not criticism.

-

Trigger plan: For each value, identify one situation that tempts drift and write a pre decision plan. For example, when pressed for time, postpone decisions that affect fairness until you can review options.

-

Public standard: Add one value behaviour to a meeting charter or ways of working document so the group can uphold it together.

-

Quarterly refresh: Repeat the audit every quarter and retire any value that has become performative. Replace it only if you are willing to define behaviours and be accountable.

Why it matters: Alignment builds trust. People judge values by what they repeatedly see, not by what is written on a wall. Research on behavioural integrity shows that perceived alignment between words and actions increases credibility, commitment, and performance. In practice, even small, consistent behaviours that serve fairness, inclusion, or stewardship create social capital that teams rely on when pressure rises. In communities, visible alignment signals care and invites others to contribute alongside you.

The deeper truth: Values do not live in statements. They live in moments. Every calendar invite, every credit shared, every listening choice is a chance to make your principles real. When your actions match your values, others feel safer and more seen. Responsibility stops being a burden and becomes a way of moving through the world with coherence. That coherence is the quiet strength people trust.

Integrity Moments Journal

Integrity is rarely tested in grand, cinematic scenes. It is tested in small choices that arrive without announcement. Do you speak up when a quiet voice is overlooked. Do you correct a minor error that benefits your side. Do you keep a promise that has become inconvenient. These moments accumulate. Over time they shape whether people experience you as trustworthy and whether your community feels safe in your presence.

An Integrity Moments Journal brings those choices into focus. Instead of assuming you act with integrity, you record concrete instances where fairness, honesty, or courage were at stake. You write what happened, what you chose, why you chose it, and what the outcome was. The purpose is not to judge yourself but to notice patterns. With awareness, you can design better conditions for responsible action and reduce the quiet drift that pressure often creates.

This exercise is simple enough to sustain and serious enough to matter. It trains a habit of reflection that turns values into lived practice.

Steps

1) Define your integrity lenses

Begin by choosing three lenses that matter to you, such as fairness, honesty, and courage. Write a one sentence definition for each in your own words. Keep the lenses visible in your journal header so they shape what you notice.

Why: Clarity about what to look for sharpens attention. When lenses are explicit, you start catching small moments that would otherwise pass unnoticed.

2) Capture one moment per day

For the next two weeks, record one situation each day where your integrity was engaged, even slightly. Note the context, who was involved, and the decision you faced. This can be as ordinary as whether to attribute a colleague’s idea or whether to question a biased comment. Keep it factual and brief.

Why: Daily capture builds sensitivity. Frequency matters more than depth at first. You are training the muscle that detects when ethical choice is present.

3) Describe the choice you made and what guided it

After each entry, write what you did and why. Include the pressures you felt, such as time, status, loyalty, convenience, or fear of awkwardness. Be honest about rationalisations you used. Name any value or principle that supported your decision.

Why: Understanding your drivers reveals patterns. You learn what nudges you toward integrity and what pulls you away. With that awareness, you can design supports and avoid traps.

4) Note the impact on people and trust

Add two quick lines on impact. Who benefited. Who was harmed or ignored. How did this affect trust in the short term and possibly in the long term. If the impact is unclear, say so and return to review it later.

Why: Responsibility lives in consequences. Considering impact widens the view beyond your intention and strengthens accountability to others.

5) Identify one refinement for tomorrow

End each entry by writing a micro adjustment you will try next time. Examples include slowing down before deciding, inviting a quiet perspective, naming a conflict of interest, or documenting a concern. Keep it specific and realistic.

Why: Small refinements compound. A daily adjustment converts reflection into practice and builds confidence that change is possible under real conditions.

Workplace examples

Attribution and credit: You notice that your summary included a colleague’s insight without naming them. In the journal you record the moment, the pressure to look decisive, and the small harm to fairness. The next day you correct the record in the team channel and adopt a habit of naming sources in notes.

Bias in a meeting: A dismissive comment is made about a contractor’s accent. You feel the room tighten and choose to say, “I want us to stay respectful. Let us focus on the idea.” You record the discomfort, the relief on two faces, and your plan to check in with the contractor afterward. The journal helps you see how small interventions set tone.

Personal examples

Keeping a promise: You had planned to help a neighbour but a long day tempts you to cancel. You keep the commitment and note that reliability is a value you want to live. You also see a pattern of overpromising and decide to commit more thoughtfully in future.

Honest conversation: A family member repeats a story that leaves out your effort. You choose to name it gently rather than let resentment build. In the journal you record your fear of conflict, the relief that followed, and the plan to speak earlier next time.

Variations

-

Three check words: At the top of each day’s entry write three words that describe the pressures you felt most, such as hurry, approval, or loyalty. Patterns will emerge within a week.

-

Weekly integrity review: Once a week, scan entries and star the one choice you are proud of and the one you wish to improve. Share one insight with a trusted peer.

-

Team practice: Invite a team to collect anonymous integrity moments and discuss themes in a retrospective. Focus on conditions that support good choices.

-

Trigger cards: From your journal, create small prompt cards, such as “slow down,” “name the source,” or “invite the quiet voice.” Keep them visible in meetings.

-

Scenario rehearsal: Choose one recurring dilemma and rehearse a better script in advance. Write the exact words you will use. Preparation lowers the cost of acting.

Why it matters: Integrity builds the trust that social responsibility requires. People believe what they repeatedly observe. Recording and reflecting on daily ethical choices increases behavioural integrity, which research links to credibility, engagement, and sustained performance. In communities, visible follow through and fairness create psychological safety and a sense of shared stewardship. Small, consistent acts of integrity become the culture others can rely on when pressure rises.

The deeper truth: Integrity is not the absence of compromise. It is the presence of consciousness. When you can see your choices clearly, you stop outsourcing your ethics to convenience or habit. You begin to act in ways that match who you intend to be. Over time, that consistency becomes quiet strength. People do not have to guess your motives. They can trust your judgment, and you can trust yourself.

Circle of contribution

Social responsibility begins close to home. Before we can act for the greater good, we must understand the web of relationships we already inhabit and how our choices affect them. Every decision we make sends ripples through this web, shaping trust, wellbeing, and collaboration. The Circle of Contribution makes that network visible.

This exercise asks you to map the people, teams, and communities your work or life touches. It then invites you to identify what you give, what you receive, and where there may be imbalance or missed opportunity. Seeing your circle laid out on paper helps you notice where your contribution is strong and where it may have weakened through neglect, overload, or lack of awareness.

The aim is not guilt or perfection. It is perspective. By visualising your contribution, you move from an individual mindset to an interdependent one. You begin to see yourself as part of an ecosystem rather than a collection of isolated roles. Over time, this awareness deepens accountability and expands care beyond immediate self-interest.

Steps

1) Map your contribution circle

Draw yourself at the centre of a page. Around you, place concentric circles labelled Close relationships, Workplace or team, Wider organisation, and Community or society. Populate each circle with names or groups you influence or depend on. This may include colleagues, clients, mentors, neighbours, or causes.

Why: Most people underestimate their reach. Seeing it visualised reveals hidden dependencies and networks of influence. Awareness expands responsibility.

2) Identify your contributions

Next to each name or group, list what you actively contribute. Contributions can be tangible (time, knowledge, support, advocacy) or intangible (trust, encouragement, example). Include what you offer voluntarily and what others rely on without asking.

Why: Articulating your contributions builds agency. It helps you see how you already serve others and where your effort has impact beyond intention.

3) Note what you receive

For each connection, write what you gain in return. This may be information, learning, friendship, emotional support, or opportunity. Acknowledge both material and relational forms of reciprocity.

Why: Recognising what you receive prevents self-importance and reinforces interdependence. Giving and receiving are equally part of responsibility.

4) Spot imbalances or gaps

Look for areas where contribution and benefit are out of balance. Are there relationships where you give without recognition or drain energy without renewal. Are there outer circles where your expertise could add value but you stay silent. Choose one imbalance to address constructively.

Why: Balance sustains contribution. Without renewal, generosity becomes depletion. Without generosity, independence becomes isolation.

5) Commit to one visible act of contribution

Select one relationship or group where you want to strengthen contribution in the next two weeks. Make the action concrete and proportionate, such as mentoring a new colleague, thanking a supplier publicly, or volunteering for a community task. Schedule it and follow through.

Why: Responsibility becomes real through behaviour. Visible contribution reinforces integrity and reminds others that care can be practical.

Workplace examples

Cross-functional contribution: A project manager realises her influence extends beyond her immediate team. She identifies operations and finance as outer-circle stakeholders who depend on her communication. She begins sending concise weekly updates to both groups. Coordination improves and small issues stop escalating.

Mentoring and renewal: A senior engineer notes that he receives continual learning from younger colleagues’ innovations but rarely reciprocates. He schedules short mentoring sessions to share institutional knowledge. Morale rises and expertise circulates more evenly.

Personal examples

Neighbourhood reciprocity: A parent recognises that they rely on neighbours for last-minute childcare but contribute little beyond friendly chats. They start organising small play swaps and share equipment. Trust deepens and the sense of mutual support grows.

Friendship maintenance: Someone sees that one long-time friend always initiates contact. They decide to take the next turn, planning a visit and writing appreciation. The friendship begins to feel balanced again.

Variation – Ripple map of impact

Once your Circle of Contribution feels clear, extend it into a Ripple Map of Impact. This version explores how each contribution affects others indirectly.

-

Select one contribution you identified earlier, such as mentoring, sharing knowledge, or improving a process.

-

Draw concentric ripples outward from that action. In the first ripple, note who benefits directly. In the second, note who benefits indirectly (for example, the mentee’s team or the customer who experiences improved service).

-

Estimate the secondary effects, such as time saved, confidence gained, or culture improved. Write both tangible and intangible outcomes.

-

Ask what conditions amplify or limit these ripples. Do they depend on communication, resources, or leadership support.

-

Reflect on sustainability. How could this ripple continue without your constant input.

Why: The Ripple Map of Impact cultivates systems thinking within emotional intelligence. It expands responsibility beyond immediate relationships and builds appreciation for the networked effects of your behaviour. Understanding ripples helps you act with foresight, designing contributions that endure and multiply.

Other variations

-

Team ripple reflection: In a team meeting, map collective contributions and discuss unseen beneficiaries. This deepens pride and shared accountability.

-

Reverse ripple: Ask others to map the ripples of your contribution from their perspective. You may discover influence you never intended but which shapes culture and morale.

-

Temporal ripple: Add a time dimension. Which actions have short-term versus long-term effects. Balance your energy accordingly.

-

Ethical ripple: For each contribution, note possible unintended harm. Responsibility includes awareness of side effects, not just intentions.

Why it matters: People thrive in systems where contribution is seen, reciprocated, and renewed. Research on prosocial behaviour shows that giving meaningfully to others enhances wellbeing, engagement, and sense of belonging. In organisations, visible contribution builds psychological safety and reinforces shared purpose. Mapping your circle clarifies not only what you do for others but how you are sustained in return. That clarity supports healthier collaboration and a more equitable distribution of effort.

The deeper truth: Social responsibility begins with recognition. Every role you hold connects you to others who depend on your integrity, generosity, and restraint. Seeing that web clearly transforms small actions into acts of stewardship. The Circle of Contribution teaches that you are never acting alone. Every choice sends ripples across relationships you may never see. When you understand those ripples, you start choosing with greater care. That care is what responsibility looks like in practice.

Service exchange

Social responsibility is not only about giving. It is also about allowing yourself to receive. Many well-intentioned people equate responsibility with self-sacrifice, as if the measure of contribution were depletion. Yet the healthiest systems, whether in teams, families, or communities, are those in which support flows both ways.

The Service Exchange exercise restores that balance. It invites you to map where you offer help and where you allow help in return. The goal is to move from one-directional generosity to sustainable reciprocity. When everyone gives and receives, energy circulates, trust grows, and belonging deepens.

In emotionally intelligent terms, this exercise strengthens empathy in action. It transforms concern for others into practical interdependence. You learn that service is not charity but partnership. It is a two-way exchange of care that keeps relationships alive and equitable.

Steps

1) List your current acts of service

Begin by writing down the ways you currently help others. Include formal and informal contributions: mentoring, covering tasks, listening, volunteering, or offering advice. Note where these acts occur within your team, your family, your social circles, or your wider community.

Why: Seeing all your giving in one place clarifies both scope and load. It also helps you identify which contributions energise you and which quietly drain you.

2) Identify where you receive support

Now list where you are on the receiving end of help. Who teaches you, backs you up, checks on you, or listens when you are under pressure. Include both emotional and practical support. If your list is short, that is useful information.

Why: Many people undervalue or avoid receiving help because they equate it with weakness. Recognising how others contribute to you builds humility and connection. It reminds you that interdependence is a strength, not a deficit.

3) Spot imbalances and assumptions

Compare the two lists. Where do you give far more than you receive. Where do you rely on others without acknowledgment. Write a short reflection on what might drive these imbalances. Is it habit, pride, time, guilt, or a belief that others will not reciprocate.

Why: Awareness exposes invisible patterns. Unequal exchanges, even unintentional, can create fatigue or resentment. Balance protects both generosity and dignity.

4) Create a service swap

Choose one person or small group with whom you can rebalance service. Offer help where you have capacity and explicitly invite help where you need it. For example, trade project feedback for mentoring, share resources in return for perspective, or alternate organising duties on a community initiative.

Why: Reciprocity builds trust faster than unilateral giving. Service swaps also model equality, showing that care is most genuine when it circulates.

4) Acknowledge contributions openly

Make it a habit to name and appreciate what others give. Write thank-you notes, mention contributions in meetings, or express gratitude in private conversation. Acknowledgment converts invisible support into visible value.

Why: Recognition fuels responsibility. When people feel seen for what they give, they are more likely to sustain their contribution without burnout.

Workplace examples

Team reciprocity: A senior consultant notices she often mentors junior staff but rarely asks for support herself. She begins a reverse mentoring relationship, learning new tools from a graduate analyst while continuing to offer coaching. Both gain confidence and respect grows across levels.

Project swap: Two departments agree to a service exchange: one provides process improvement expertise, the other offers data analysis in return. Each saves time, builds appreciation, and reduces the “us versus them” mindset.

Personal examples

Family balance: A parent realises they take on most household logistics. They create a “service swap” chart where tasks rotate weekly. Family members begin to appreciate the effort behind daily routines, and relationships feel more cooperative.

Friendship reciprocity: One friend is known for emotional support but struggles to ask for help. She decides to share a personal challenge instead of staying in the listener role. The friend responds with care, deepening trust and balance.

Variations

-

Service inventory: Once a quarter, record all the people and groups you help. Mark which interactions are mutual and which are one-sided. Identify one to rebalance.

-

Invisible labour audit: With a team, list tasks that sustain others but are often unacknowledged, such as organising, note-taking, or emotional care. Rotate these roles.

-

Reciprocity circles: In small groups, each person states one thing they can offer and one thing they need. Match exchanges. This works well in leadership retreats or communities of practice.

-

Reverse exchange: Choose someone who usually helps you and find a small, meaningful way to reciprocate: even symbolic acts matter.

-

Ripple reflection: Link this to the previous exercise by mapping how reciprocal acts of service create secondary benefits, such as increased morale or learning across boundaries.

Why it matters: Research in social and organisational psychology consistently shows that reciprocity strengthens cooperation and trust. Teams that balance giving and receiving demonstrate higher morale and lower burnout. When individuals both contribute and accept support, they report greater wellbeing and belonging. Reciprocity is also a safeguard against the emotional fatigue that can accompany over-responsibility. It keeps compassion renewable.

The deeper truth: True responsibility does not mean doing everything yourself. It means participating in the shared care of the world around you. When you allow help in as readily as you offer it, you acknowledge a deeper truth: that dignity lies in mutuality. Service is not a one-way act of generosity but a living exchange that connects people in respect and gratitude. Every time you give and receive with openness, you strengthen the fabric of trust that holds communities together.

Ethical foresight pause

Social responsibility often reveals itself in moments of decision. These are not always headline-making choices about right and wrong, but everyday decisions about fairness, inclusion, or priorities. In fast-moving environments, it is easy to act on habit or pressure, telling ourselves we will reflect later. The problem is that later rarely comes. The Ethical Foresight Pause creates that moment of reflection before the decision, when it can still shape the outcome.

This exercise introduces a structured way to think before acting. It slows down impulsive reasoning, invites multiple perspectives, and helps you weigh the broader consequences of your choices. Instead of asking, “What should I do right now,” you learn to ask, “What will this decision mean for others later.”

Practised consistently, this small pause builds ethical maturity. You learn to hold tension between competing needs: performance and fairness, loyalty and truth, ambition and care. The aim is not perfection but perspective. Responsibility begins with remembering that every choice sits within a system of people, values, and ripple effects.

Steps

1) Recognise the decision moment

Notice when you are about to make a choice that affects others: approving a policy, assigning work, delivering feedback, or allocating resources. These are ethical moments, even when they seem routine. Mark them mentally as “pause points.”

Why: Ethical blind spots often occur in speed or habit. Recognising decision moments transforms ordinary actions into opportunities for conscious responsibility.

2) Pause and surface the context

Take a short break, even thirty seconds, to step back from urgency. Ask yourself: What is at stake here? Who is affected? What pressures or assumptions are shaping my reaction? Write a few quick notes if possible, or run these questions silently before responding.

Why: Pausing interrupts automaticity. It allows your prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and empathy, to re-engage before the moment of choice.

3) Run the ethical foresight questions

Use these five short prompts to test your decision:

-

Who gains and who loses if I act this way?

-

What values or principles are being upheld or violated?

-

How would I explain this decision to the people affected?

-

What unintended consequences might emerge later?

-

What choice would build the most trust, not just the most convenience?

Why: Structured questioning transforms vague ethical intuition into deliberate reasoning. It makes invisible trade-offs visible and integrates both logic and care.

4) Consult a perspective outside your own

If time allows, check your reasoning with someone who sees the world differently; a colleague from another team, a stakeholder, or a trusted peer. Ask, “How does this look from where you stand?” or “What might I be missing?”

Why: Perspective-taking reduces bias and broadens fairness. It anchors ethical judgment in diversity rather than assumption.

5) Decide and document the reasoning

Make your choice and note in one or two lines why you made it, especially if you hold a position of influence. Even a short record of your reasoning improves transparency and helps others learn from your process.

Why: Ethical foresight grows stronger through traceability. Writing down rationale promotes accountability and consistency, especially in leadership.

Workplace examples

Resource allocation: A manager must choose between funding a high-profile innovation project and maintaining a small support programme for vulnerable customers. Using the foresight questions, she realises the latter aligns more strongly with the organisation’s values of inclusion and service. She maintains the support funding and communicates the reasoning transparently, earning credibility across teams.

Performance feedback: A leader considers giving gentle but vague feedback to avoid discomfort. The pause reveals that kindness without clarity undermines fairness and growth. He chooses direct but compassionate honesty, guided by the value of respect.

Personal examples

Neighbourhood decision: A community volunteer debates whether to exclude a late-paying member from an event. The foresight pause highlights that inclusion and dignity matter more than minor loss. She decides to welcome them, strengthening community trust.

Family dilemma: A parent considers cancelling an outing after a stressful week. The pause reveals that the deeper value is reliability. They choose to go, modelling follow-through and balance for their children.

Variations

-

Team decision ritual: Before approving a major initiative, teams run the five foresight questions together. The discussion takes five minutes and surfaces unseen implications early.

-

Ethics check column: Add a brief “values impact” note to decision documents or project templates to embed reflection into workflow.

-

Reverse foresight: After a challenging decision, replay it using the same five questions. Identify what you would do differently next time.

-

Ethical buddy system: Pair with a peer who agrees to serve as a “reflection partner” when you face ambiguous choices.

-

Pressure pause drill: Practise pausing in low-stakes moments, such as deciding email tone or meeting timing, so the habit is ready when pressure rises.

Why it matters: Ethical reasoning depends on time and awareness. Under pressure, people default to self-protection or conformity. Research on moral decision-making shows that deliberate reflection increases fairness, reduces ethical lapses, and strengthens trust within teams. The Ethical Foresight Pause creates that reflective micro-moment in fast contexts. Over time, it builds a culture where integrity is expected, not exceptional.

The deeper truth: Most ethical failures are not caused by malice but by momentum. People act quickly, assume good intent, and move on. Responsibility asks for a different rhythm. A pause. A question. A wider lens. The Ethical Foresight Pause teaches that conscience is not a sudden voice but a cultivated practice. Each time you stop to consider who is affected and what values are in play, you strengthen both your moral clarity and your humanity. Responsibility begins in a single breath of reflection.

Community micro-action

Social responsibility is at its strongest when it moves beyond awareness into action. It is one thing to care about fairness, inclusion, or wellbeing in theory. It is another to do something about it, however small. The Community Micro-Action exercise bridges that gap. It helps you turn your values into tangible behaviour, not through grand gestures or corporate campaigns, but through consistent, visible, local acts that strengthen the fabric of community.

In the EQ-i model, social responsibility means acting as a cooperative, constructive member of the groups you belong to. Micro-actions embody that principle. They are small, intentional contributions that signal, “I am part of this, and I care about our collective wellbeing.” Examples might include mentoring a new employee, organising a shared resource for your neighbourhood, improving accessibility in your workplace, or simply initiating honest conversations about how to make the environment fairer for all.

What matters is not scale, but sincerity. Research on prosocial behaviour shows that even small contributions increase wellbeing and belonging for both the giver and the receiver. Over time, consistent micro-actions create a culture of mutual support, a visible reminder that social responsibility is not an abstract ideal but a lived daily practice.

Steps

1) Choose a community that matters to you

Begin by identifying one community where you belong and can make a difference. This could be your team, department, professional network, neighbourhood, volunteer group, or online community. Clarify why this community matters to you, what shared values or needs connect you to it.

Why: Responsibility without belonging feels abstract. Focusing on a real community creates emotional connection and accountability. You care more when the group’s wellbeing affects your own.

2) Identify one small, meaningful gap

Ask yourself: What is missing or under-served here? Where could things be fairer, easier, kinder, or more inclusive? This might be a lack of mentorship, recognition, or psychological safety. Look for small leverage points where effort would make a visible difference.

Why: Social change begins with noticing. Small, specific gaps are more actionable than abstract ideals. You do not need to fix everything, you only need to start somewhere that matters.

3) Design your micro-action

Define one act you can take within your capacity and influence. Keep it simple and sustainable: starting a peer support circle, sharing knowledge openly, checking in on isolated colleagues, or introducing a more inclusive practice in your team. Ensure it aligns with your values and the community’s needs.

Why: Intentionality distinguishes action from impulse. Designing a specific behaviour creates focus and makes follow-through more likely.

4) Invite others to participate

Social responsibility multiplies when shared. Once your micro-action is underway, invite one or two others to join or build on it. Frame it as an opportunity, not an obligation: “I’ve started doing this small thing to make our team work better, would you like to join me?”

Why: Collaboration transforms contribution into culture. When others see responsibility as shared, they are more likely to act and sustain change beyond your personal effort.

5) Reflect and renew

After a few weeks, pause to review. What changed? Who benefited? How did it feel? What did you learn about your community, and about yourself? Use these insights to refine or evolve your action — perhaps passing leadership to someone else or starting a new initiative.

Why: Reflection completes the learning cycle. It turns action into wisdom and prevents good intentions from fading into one-time gestures.

Workplace examples

Peer mentoring micro-action: A software engineer notices new graduates struggling to navigate onboarding. She starts a “peer buddy” system, pairing newcomers with experienced colleagues for informal support. The time investment is minimal, but morale and retention improve.

Inclusion micro-action: A manager realises that remote staff rarely speak in team meetings. He starts rotating facilitation duties so each person leads occasionally. The small change increases engagement and ensures all voices are heard.

Personal examples

Neighbourhood care: A resident observes that elderly neighbours struggle with digital tools for local updates. He creates a printed version of key information each month and delivers it personally. Over time, the gesture builds trust and connection among generations.

Community learning: A parent joins a local sustainability group and volunteers to host short workshops on waste reduction. Attendance grows, and a sense of shared agency emerges, people feel capable, not overwhelmed.

Variations

-

One-hour action: Dedicate one hour a month to a specific contribution outside your normal role; mentoring, volunteering, or advocacy. Keep a record of actions and outcomes.

-

Team micro-pledge: At the end of a meeting, ask everyone to name one small way they can strengthen team wellbeing this week. Revisit next meeting.

-

Skill-sharing chain: Each person teaches one skill or insight to someone else, who then pays it forward. This creates a continuous loop of contribution.

-

Kindness in systems: Instead of random acts of kindness, look for structural kindness; policies, norms, or routines that make fairness automatic.

-

Community ripple mapping: Combine with Exercise 3 by drawing the ripple effects of your micro-action; who benefits directly, and who indirectly as a result.

Why it matters: Psychological and organisational research shows that consistent small contributions have a disproportionate impact on collective wellbeing. They increase trust, belonging, and motivation across groups. Studies in positive psychology also find that altruistic acts strengthen life satisfaction and reduce stress by shifting focus from self-concern to shared purpose. Community micro-actions are how responsibility becomes visible: they show that everyone has power to make things better, however modestly.

The deeper truth: Responsibility without action is only awareness. The Community Micro-Action reminds us that contribution does not require authority or grand resources, only intention and follow-through. Every small act of fairness, care, or inclusion signals that the community matters and that we matter to it. When you make responsibility tangible in your daily life, you turn empathy into structure, values into movement, and belonging into reality. Over time, these small ripples form the culture you wish existed.

Responsibility boundary map

Social responsibility becomes unsustainable when we take on what is not ours to carry. Many leaders over-give not because they lack boundaries, but because they lack clarity about them. They absorb others’ tasks, worries, and emotional burdens out of care, competence, or habit. Over time, this blurs roles, weakens collaboration, and drains energy that should be directed toward meaningful contribution. The Responsibility Boundary Map brings that landscape into focus.

This exercise helps you identify what is genuinely your responsibility, what belongs to others, and where you may be stepping in out of guilt, fear, or over-functioning. It invites you to see the invisible lines around your work, your relationships, and your emotional labour. Mapping these boundaries does not reduce care. It strengthens it by ensuring that your contribution is grounded, appropriate, and sustainable.

The aim is not to withdraw or protect yourself excessively. It is to make responsibility accurate. When you work within your appropriate scope, you support others without rescuing them, collaborate without losing yourself, and contribute in ways that are both effective and healthy. Clear boundaries are not barriers to responsibility. They are the conditions that make responsibility real.

Steps

1) Define what is yours to hold

At the top of a page, write three headings: Tasks, Decisions, and Emotional Labour. Under each, list what genuinely sits within your role or responsibility. Include what you are accountable for, what you control, and what people rightly expect from you.

Why: Most overload begins with blurred categories. Naming what is yours creates a foundation for noticing where you may be absorbing unnecessary load.

2) Identify what belongs to others

Next, create a second list. Under the same three headings, map what clearly sits with other people. This may include colleagues’ tasks, your team’s decision-making, or emotions that are not yours to manage or fix.

Why: Seeing others’ responsibilities on paper reduces the impulse to step in automatically. It builds respect for their autonomy and competence.

3) Spot the boundary crossings

Circle any items where you tend to cross the boundary. These may be tasks you take over to be helpful, decisions you escalate or absorb unnecessarily, or emotions you carry on behalf of others. Write briefly why you step in. Common reasons include wanting control, avoiding conflict, feeling needed, or fearing disappointment.

Why: Boundary crossings are often unconscious. Bringing them into awareness reveals the emotional drivers behind over-responsibility. Awareness creates choice.

4) Clarify your healthy zone of responsibility

Draw two concentric circles. In the inner circle, write what you will actively own. In the outer circle, write what you will support without taking on. Support might include coaching, offering clarity, or providing resources rather than doing the work yourself.

Why: Healthy responsibility is neither withdrawal nor over-functioning. Defining a support zone maintains care while protecting sustainability.

5) Choose one boundary reset

Select one boundary you want to strengthen in the next week. This might be delegating a task fully, delaying your impulse to fix someone’s stress, or redirecting a question back to the person responsible. Plan the wording you will use and the moment you will apply it.

Why: Boundaries gain strength through behaviour, not intention. One small reset can shift relational expectations and restore balance.

Examples

Role clarity reset: A team leader realises she routinely takes over tasks during crises. She identifies these as her team’s responsibilities and reframes her role as coaching rather than rescuing. Accountability increases and stress reduces across the team.

Emotional overreach: A manager notices he often absorbs colleagues’ frustration and carries it home. By mapping emotional labour, he distinguishes empathy from ownership and begins validating feelings without internalising them.

Decision ownership: An executive recognises he makes decisions one level below his remit. He returns decisions to the appropriate owners with support, increasing empowerment and reducing bottlenecks.

Family load: A parent realises they routinely solve adult children’s problems. They shift from fixing to guiding. Relationships become more respectful and less dependent.

Friendship imbalance: Someone notices they hold more emotional weight in a friendship than the other person. They reset the balance by sharing honestly and encouraging mutual responsibility.

Community involvement: A volunteer recognises they keep taking on extra roles because others avoid stepping up. They set limits and help the group redistribute tasks more fairly.

Variations

- Boundary labelling: Place a coloured mark next to each boundary crossing indicating emotional drivers, such as fear, habit, or control.

- Responsibility conversation: Share your map with a colleague or partner and align on shared boundaries.

- Delegation audit: Create a boundary map specifically for delegation. Identify what you should release and what prevents you from doing so.

- Emotional labour diary: For one week, note emotional loads you carry that do not belong to you. Patterns become visible quickly.

Why it matters: Research on prosocial behaviour shows that sustained contribution depends on clear psychological and relational boundaries. When people take on too much, they become exhausted, resentful, or controlling. When responsibility is accurately held, teams function more effectively, relationships become more balanced, and individuals feel more autonomy and trust.

Healthy boundaries also strengthen empathy, because they allow care without self-loss. They reinforce integrity by helping leaders act from principle rather than pressure. Ultimately, responsibility is most powerful when it is chosen, not absorbed.

The deeper truth: Boundaries are not walls. They are commitments to what is true. When you understand what is yours to hold, you stop rescuing, overreaching, or trying to compensate for others’ avoidance. You begin contributing from clarity, not compulsion.

The Responsibility Boundary Map reminds us that responsibility is a shared space, not a solo burden. When you hold your part well and let others hold theirs, you create conditions where everyone can act with maturity, integrity, and care. In that balance, social responsibility becomes both sustainable and transformative.

Collective impact reflection

Social responsibility does not end at the boundaries of our immediate roles. Every action, decision, and behaviour contributes to a wider system: a team culture, an organisational climate, a community, or a social environment. Much of this impact is invisible in the moment. We see only the task completed, the message sent, or the behaviour displayed, but not the broader effects that ripple outward. Collective impact reflection helps bring these wider consequences into awareness.

This exercise invites you to zoom out from the personal to the collective. It challenges you to consider how your choices influence the wellbeing, confidence, cohesion, or culture of the groups you belong to. It moves social responsibility from a series of individual actions to an understanding of yourself as part of a living system, where even small decisions accumulate and shape the environments around you.

The goal is not to create pressure to be perfect. It is to cultivate foresight and humility. When you reflect on your broader impact, you begin to see how your presence contributes to or detracts from the collective. You recognise that leadership is not only what you do intentionally, but also what you do inadvertently. Over time, this awareness strengthens integrity, deepens care, and encourages choices that support the group as a whole.

Steps

1) Identify a recent action or decision

Choose one event from the past week where you contributed to a task, conversation, or decision. It might be a meeting intervention, an email you sent, feedback you gave, or support you offered to someone.

Why: Starting with a single, concrete moment grounds the reflection. It is easier to see impact clearly when you narrow your focus.

2) Map the direct impact

List the people who were directly affected by your action. Note how the event influenced them in practical and emotional terms. Consider clarity, workload, confidence, motivation, or stress.

Why: Direct impact is the first ripple. Seeing it explicitly reminds you that your actions rarely land in isolation.

3) Explore the indirect impact

Move one ripple further. Ask: “Who else was affected because the first group was affected?” This may include team members who experienced the downstream effects, customers who felt the quality shift, or colleagues whose decisions relied on yours.

Why: Most meaningful impact happens indirectly. Developing sensitivity to secondary effects is a hallmark of socially responsible leadership.

4) Consider the cultural or systemic influence

Ask yourself how your action influenced the broader norms or culture. Did it reinforce transparency, respect, inclusion, or accountability? Or did it unintentionally strengthen avoidance, urgency, silence, or dependency?

Why: Systems are shaped by repeated behaviours. Understanding cultural impact helps you act with intention rather than habit.

5) Identify one future shift

Based on what you see, choose one small adjustment you could make next time to enhance the collective good. This might be communicating earlier, seeking input, sharing credit, or slowing down to clarify expectations.

Why: Reflection without adjustment is insight without influence. A small shift, repeated over time, shapes cultures as much as large initiatives.

Examples

Team morale ripple: A manager realises that her brief acknowledgement of a colleague’s hard work not only boosted one person’s confidence but also signalled to the entire team that effort is recognised. She decides to integrate small recognitions into weekly meetings.

Clarity ripple: An engineer notices that unclear instructions created confusion for two colleagues and indirectly slowed another team’s timeline. He commits to adding a clarity check to all technical messages.

Presence ripple: A leader reflects on a moment of visible frustration during a meeting. While the issue was minor, the ripple included increased anxiety across the room. He resolves to settle himself before entering challenging discussions.

Family atmosphere: Someone realises that rushing anxiously through their morning routine influences the whole household. They shift to preparing the night before to create a calmer start for everyone.

Community involvement: A neighbour notices that greeting others consistently changes the tone of the street, increasing warmth and connection. They commit to doing it more intentionally.

Friendship ripple: A person reflects that cancelling plans last-minute caused inconvenience for one friend and created tension across a wider group. They set a boundary to avoid overcommitting.

Variations

- Ripple diary: At the end of each day, choose one action and write its first and second ripple.

- Group ripple discussion: With your team, reflect on how collective actions shape culture. Identify positive ripples to reinforce.

- Impact lens for decisions: Before making a decision, pause and ask, “What are the likely first and second ripples?” Then refine your approach.

- Anonymous ripple audit: Invite trusted colleagues to share how your actions ripple outward. This expands insight beyond self-perception.

Why it matters: Collective impact reflection builds systems thinking within emotional intelligence. Research on organisational behaviour shows that individuals often underestimate the influence of seemingly small behaviours on the group. Leaders who understand their ripple effects act with greater ethical awareness, strengthen trust, and cultivate climates where people feel considered and respected.

This practice also prevents over-responsibility by clarifying what kinds of influence you truly hold and what lies outside your reach. It builds humility as well as agency. Over time, collective impact thinking shifts organisations from reactive silos to interdependent systems rooted in shared accountability.

The deeper truth: Every action becomes part of a larger story. Whether you intend it or not, your behaviour shapes the emotional and relational landscape around you. When you begin to see the wider effects of your choices, responsibility becomes less about effort and more about awareness.

Collective impact reflection teaches that leadership is not confined to moments of high visibility. It is woven through the small, ordinary decisions that accumulate into culture. When you act with foresight and care, you help build environments where people can thrive. That is the essence of social responsibility.

Conclusion: Serving with integrity

Social responsibility is not a fixed trait or a single act of goodwill. It is a practice of alignment between values and behaviour, empathy and action, self and community. It asks us to hold two truths at once: that our choices matter to others, and that the wellbeing of others sustains us in return. Every day offers moments, large and small, where this alignment is tested. How we respond defines the quality of our relationships and the integrity of our leadership.

When social responsibility fades, systems become efficient but hollow. People begin to optimise tasks rather than care for outcomes. Decisions lose moral weight. By contrast, when responsibility is alive, it brings warmth to structure and conscience to ambition. Teams grounded in fairness and contribution are not only more ethical; they are more resilient and innovative. They move through conflict with respect because they share a deeper commitment to one another’s success.

The six practices in this chapter are not moral lessons but practical lenses. Each one makes the invisible visible. A Values-to-Action Audit grounds intention in behaviour. An Integrity Moments Journal sharpens awareness of daily choices. A Circle of Contribution widens perspective beyond the self. Service Exchange keeps generosity reciprocal. The Ethical Foresight Pause protects against short-sighted decisions. And Community Micro-Actions translate caring into concrete change. Together, these practices cultivate a habit of stewardship, a way of living and working that honours both individuality and interdependence.

Social responsibility does not ask for perfection, only presence. It invites you to consider the ripple effects of your actions and to choose contribution over indifference. When you act with integrity and care, you strengthen more than relationships. You strengthen the invisible fabric of trust that allows groups, organisations, and societies to endure.

Reflective questions

-

Which of the six practices feels most natural to you, and which one stretches your current habits of care or fairness?

-

In what areas of your work or community life do you tend to overgive or undergive? What would balance look like?

-

When have you seen integrity in action from someone else, and how did it affect your trust in them?

-

What is one small, visible act you could take this week to strengthen the wellbeing of your team, family, or community?

-

How might your influence change if you treated every interaction as an opportunity to leave the system stronger than you found it?

Social responsibility begins quietly, in how you listen, how you decide, and how you treat those without power to repay you. Over time, these moments form a pattern of trust and care that others can feel. In this sense, social responsibility is not an obligation but a privilege: the chance to act as a steward of the shared spaces we all depend on.

Do you have any tips or advice on raising social responsibility?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Social Responsibility is one of the three facets of Interpersonal realm that also includes Empathy and Interpersonal Relationships.

References

Bar-On, R. (1997) BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) Technical Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Block, P. (2011) Flawless Consulting: A Guide to Getting Your Expertise Used. 3rd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Block, P. (1993) Stewardship: Choosing Service Over Self-Interest. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Edmondson, A. (1999) ‘Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp. 350–383.

Gardner, H. (2011) Truth, Beauty, and Goodness Reframed: Educating for the Virtues in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Basic Books.

Keltner, D. (2016) The Power Paradox: How We Gain and Lose Influence. New York: Penguin Press.

Stein, S. J. and Book, H. E. (2006) The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons Canada.

Leave A Comment