We live in a time of constant connection but fleeting closeness. Messages travel faster than meaning, and collaboration often happens through screens rather than shared spaces. In such a climate, maintaining real relationships requires more than communication. It requires presence, the capacity to build trust, mutual respect, and genuine care across the noise of daily work and life.

In the EQ-i model, Interpersonal Relationships are defined as the ability to establish and maintain mutually satisfying relationships that are characterised by trust, compassion, and giving and receiving support (Stein & Book, 2011). It is the emotional intelligence skill that turns interaction into connection. At its heart, it asks: do the people around you feel seen, valued, and safe with you, and do you feel the same with them?

When interpersonal connection weakens, the costs ripple widely. In workplaces, tasks continue but energy fades. Conversations become transactional, and collaboration turns into coordination without warmth. People feel lonely even in teams. In personal life, relationships thin into logistics, with updates replacing intimacy and proximity replacing presence. Over time, the absence of meaningful connection leads to burnout, cynicism, and disengagement (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008).

Strong interpersonal relationships, by contrast, act as a buffer and a source of vitality. They provide psychological safety, belonging, and resilience. Research consistently shows that people with strong social ties experience greater well-being, lower stress, and higher performance (Fredrickson, 2001; Dutton & Heaphy, 2003). In organisations, teams grounded in trust and mutual care solve problems more creatively and recover more quickly from setbacks.

Interpersonal skill is not about being extroverted or sociable. It is about being available, emotionally, mentally, and relationally. It is the ability to offer presence without pretense and to receive it without defence. This means caring enough to listen, trusting enough to be honest, and humble enough to both give and receive help.

Why interpersonal relationships matter

If interpersonal relationships are the foundation of collaboration and care, why do they often receive less attention than performance or productivity? The answer lies in habit. Many people assume that relationships form naturally, yet in reality, they are sustained by intention.

Emotional resilience through connection

Strong relationships buffer stress. People cope better when they feel supported and valued. In a high-pressure environment, knowing that someone has your back provides both psychological safety and courage to take risks.

Better collaboration and decision-making

Teams that trust one another share information freely and challenge ideas without fear. This leads to better solutions and faster recovery from mistakes. Trust turns debate into dialogue and disagreement into discovery.

Greater engagement and wellbeing

People are energised when they feel part of something larger than themselves. Research shows that social connection is one of the strongest predictors of happiness and health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). The strength of your relationships determines the strength of your motivation.

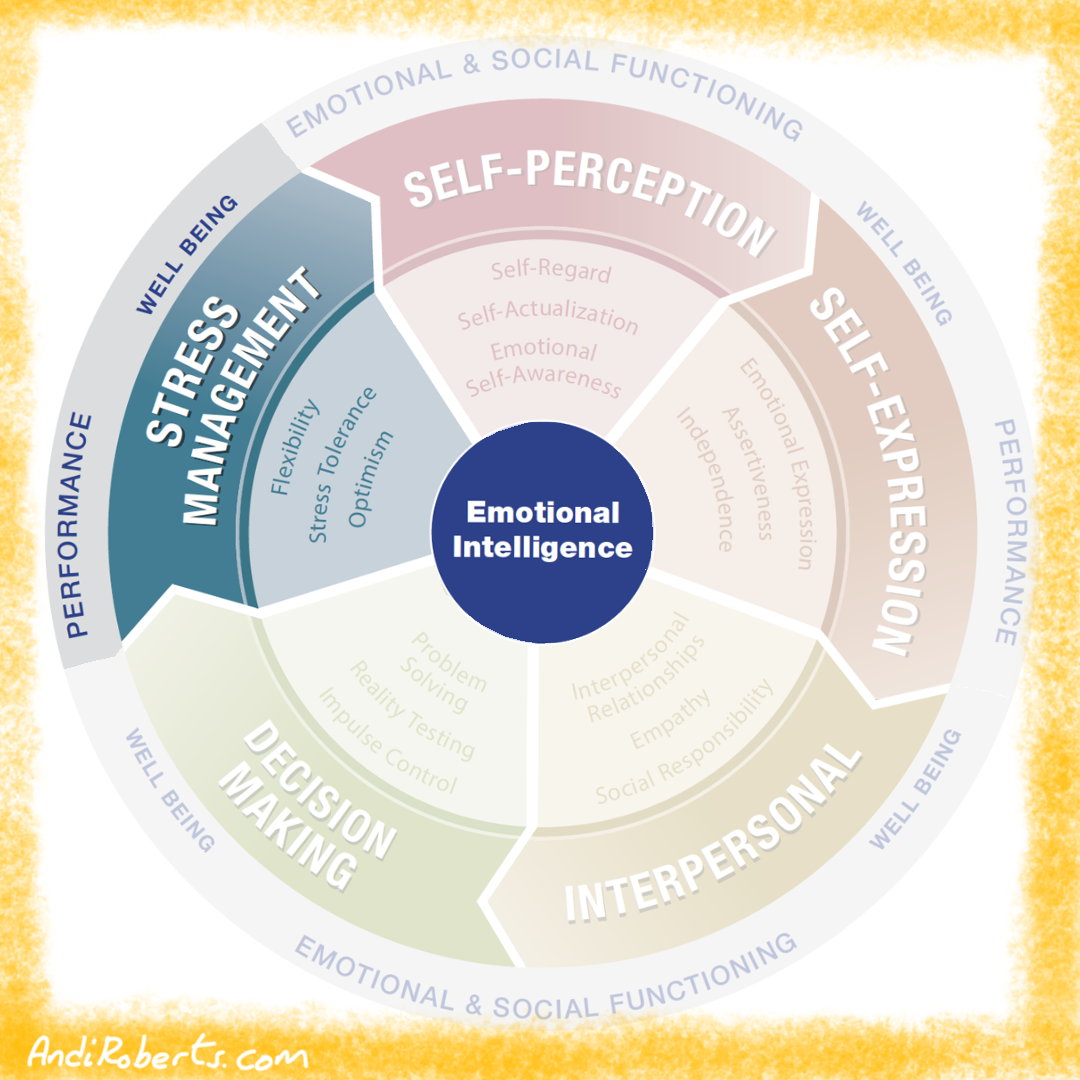

A core competency in the EQ-i model

In the EQ-i framework, interpersonal relationships are not a soft skill but a central pillar of emotional intelligence. They integrate empathy, social responsibility, and communication into a single, sustaining force. Without strong relationships, emotional intelligence remains theoretical. With them, it becomes visible in everyday life, in how you respond, how you listen, and how you show care.

Levels of expression: low, balanced, and overused

Interpersonal relationships reflect the capacity to build and maintain mutually satisfying connections grounded in trust, empathy, and genuine care. In the EQ-i model, this composite describes how a leader navigates closeness, reciprocity, and relational presence. The developmental question is not simply whether a leader is sociable, but how proportionately they engage in emotional connection across different contexts. When expressed in balance, this capability supports collaboration, psychological safety, and long-term trust. When underused it results in distance, emotional guardedness, and difficulty forming meaningful bonds. When overused it can become intrusive, overly personal, or boundary-blurring. The table below summarises how this composite typically presents across low, healthy, and overused expression.

|

Low |

Balanced |

Overused |

|---|---|---|

|

Does not like or avoids intimacy. |

Able to build mutually satisfying relationships. |

Struggles when working alone or without social input. |

|

Not giving or emotionally responsive. |

Gives and receives support, affection, and connection. |

Invades personal space or becomes overly familiar. |

|

Shows little interest in relationships. |

Maintains relationships over time with reliability. |

Shares too much information or becomes emotionally exposing. |

|

Unable or unwilling to express feelings. |

Feels at ease in social situations and adapts well. |

Becomes overly revealing, intense, or boundary-blurring. |

|

Prefers isolation; operates as a loner. |

Balances connection with professionalism. |

Demonstrates clinginess, dependency, or inappropriate intimacy. |

Balancing factors that keep interpersonal relationships healthy and grounded

In the EQ-i framework, interpersonal relationships are strengthened and shaped by other emotional capabilities that support balanced connection. These balancing factors ensure that relational warmth does not collapse into dependency, that openness does not compromise boundaries, and that care does not override clarity.

Self actualisation: Self actualisation provides an internal anchor that prevents relationships from being used to fill emotional gaps. When leaders feel fulfilled, purposeful, and engaged in meaningful pursuits, they bring connection from a place of abundance rather than neediness. This ensures relationships are mutual, not compensatory. Leaders with strong self actualisation can offer genuine presence while maintaining their own direction, preventing interpersonal relationships from tipping into over-reliance or over-sharing.

Problem solving: Problem solving maintains steadiness in relationships by ensuring that emotion does not overshadow practical reality. It helps leaders address relational tensions constructively, resolve misunderstandings, and respond to conflict with clarity rather than avoidance or over-accommodation. Strong problem solving also allows leaders to distinguish relational challenges from operational ones, preventing emotional closeness from biasing decisions or clouding judgement.

Independence: Independence provides the boundary that protects relational health. Leaders with strong independence are capable of emotional closeness without losing autonomy. They can connect deeply while maintaining their own perspective, responsibilities, and sense of self. Independence prevents overuse of interpersonal relationships by balancing connection with self-reliance, ensuring that support-seeking and intimacy remain appropriate and contextually grounded.

Eight practices for building strong interpersonal relationships

Like all dimensions of emotional intelligence, relationships do not thrive by chance. They grow through daily habits of awareness, appreciation, and repair. The eight exercises that follow offer practical pathways to strengthen trust and connection. Some focus on reflection, such as auditing your network or tracking reciprocity. Others build behaviour in the moment, such as initiating repair or expressing appreciation. Together, they form a toolkit for relational depth.

Each exercise is structured in the same way:

- Overview explains the purpose and spirit.

- Steps guide you through the process.

- Examples show how it looks in real contexts.

- Variations offer ways to adapt.

- Why it matters grounds the practice in research and insight.

These practices are not about networking or charm. They are about cultivating the emotional habits that keep relationships alive: awareness, honesty, gratitude, and care. Interpersonal relationships are, in the end, not about who we know, but how we know them. They remind us that strength lies not in independence but in interdependence, and that connection, once nurtured, becomes both a source of resilience and a measure of humanity.

1 – Relationship audit

We rarely lose relationships in dramatic ways. They fade quietly through busyness, assumption, or neglect. We tell ourselves that trust is solid, that connection will resume when things calm down. But relationships, like fitness, weaken without attention. A relationship audit is a deliberate pause to notice who matters most, how connected you feel, and where renewal is needed.

In the EQ-i model, Interpersonal Relationships means forming and maintaining mutually satisfying bonds built on trust and compassion (Stein & Book, 2011). This competency is not about being sociable; it is about being intentional. Healthy relationships thrive when they are monitored and maintained, not left to drift on goodwill alone.

A relationship audit works like a health check. It helps you see which relationships are thriving, which are distant, and which need repair. People with strong relational awareness act early; they sense when tension or distance appears and respond before it hardens. Those who lack it often wait until the damage is done. An audit brings relationships back into conscious stewardship.

Steps

1 – Map your key relationships

Begin by listing eight to ten people who significantly affect your work or wellbeing. Include colleagues, customers, stakeholders, friends, mentors, and family members. Think broadly about influence and emotional impact, not just formal hierarchy or proximity. Who shapes your decisions? Whose energy lifts or drains you? Whose trust matters most to your success and happiness? Writing these names down transforms vague feelings into a visible network. You start to see your relational world as an ecosystem that needs conscious tending rather than something that simply exists.

Why: Clarity begins with visibility. Most people underestimate how many relationships quietly shape their experience. A written list externalises this hidden architecture, revealing where attention is concentrated and where it has quietly faded.

2 – Rate trust and connection

Next to each name, give two simple ratings from 1 to 5. The first, Trust, reflects how safe, reliable, and honest the relationship feels. The second, Connection, measures the sense of emotional closeness or the frequency and quality of recent contact. Be instinctive rather than analytical—your first impression is often the most accurate. A five in both categories represents a strong, mutually supportive relationship; lower scores highlight distance, tension, or neglect. Patterns begin to emerge quickly: who you rely on most, who you’ve lost touch with, and where energy might need to shift.

Why: Two numbers can reveal more than long reflection. High trust but low connection often points to a neglected friendship that could be easily rekindled. High connection but low trust may signal a relationship that looks busy on the surface but feels uneasy underneath. Quantifying helps the emotional become actionable.

3 – Identify relational zones

Once the ratings are complete, group your relationships into four broad zones. Thriving relationships combine high trust and high connection: they are solid foundations that deserve appreciation and maintenance. Distant relationships hold trust but lack regular contact; these are sleeping allies waiting for a small spark of renewal. Fragile relationships are active but uncertain—perhaps marked by misunderstandings or mismatched expectations. Strained relationships score low on both measures and may require careful reflection before re-engagement. Seeing these zones mapped out creates a relational dashboard of your world at a glance.

Why: Categorising makes priorities visible. You cannot nurture everyone equally, and not all relationships need the same kind of attention. This step helps you distinguish between those to appreciate, those to revive, and those to approach with care or boundaries.

4 – Choose one focus relationship

Select one relationship from your “distant” or “fragile” zones to focus on this month. Think of a small, specific action that would strengthen trust or increase connection. It might be sending a message of appreciation, scheduling a short conversation, or addressing a misunderstanding you’ve been avoiding. Choose an action that feels meaningful yet achievable within the next week. This focused experiment keeps the audit practical and builds momentum.

Why: Focus prevents overwhelm. Trying to repair or nurture every relationship at once creates paralysis. Choosing one allows visible progress and reinforces the belief that relationships change through steady intention, not grand reinvention.

5 – Schedule review

Finally, treat this as an ongoing practice rather than a one-time reflection. Mark a reminder in your calendar to repeat the audit monthly or quarterly. Each round should be quicker and sharper. Over time, you will see which relationships are deepening, which have drifted again, and which remain persistently strained. Adjust your actions accordingly.

Why: Relationships evolve constantly. Regular review turns connection from a reactive habit into a deliberate rhythm. When you make space for reflection, you catch small signs of drift before they become disconnection.

Workplace examples

Project partner drift: A manager realises her once-trusted peer has gone quiet since a reorganisation. She schedules a short catch-up coffee, learns about new challenges, and re-establishes collaboration.

Team imbalance: A team leader notices he invests most energy in high performers while neglecting quieter contributors. He begins two-minute weekly check-ins, which lift engagement across the team.

Personal examples

Friendship neglect: Someone scores high trust but low connection with an old friend. They send a quick voice note: “I miss our talks. Want to catch up soon?” The friendship warms again.

Family strain: A parent rates low trust and low connection with a teenager. They introduce a weekly no-agenda chat, focusing on curiosity rather than correction, slowly rebuilding closeness.

Variations

- Visual map: Draw your network as circles, placing people closer or farther based on connection. Colour-code by trust.

- Team audit: Teams rate connection across the group, then discuss results in a safe, open dialogue.

- Quarterly habit: Repeat seasonally to track change and momentum.

- Reciprocity lens: Add a column for “Am I mostly giving or receiving?” to reveal hidden imbalances.

Why it matters: Research on social capital shows that diverse, well-maintained relationships increase wellbeing, innovation, and resilience (Cross & Parker, 2004). When ties decay, communication falters and opportunities narrow. Relationship audits prevent quiet erosion by turning attention into action. They remind us that connection, like any valuable asset, must be reviewed, renewed, and reinvested in.

The deeper truth: Connection is a form of stewardship. Most people manage projects with discipline but relationships by assumption. A relationship audit reverses that equation. It says: these people matter, and I will not leave our connection to chance. Each name on your list represents a thread of trust that needs tending. When you care for those threads, you strengthen not just your network but your sense of belonging.

2 – Five-minute check-in

Relationships often weaken not through conflict but through silence. We get busy, assume people know we value them, and postpone simple conversations until connection becomes awkward. Yet trust grows less from grand gestures and more from small, consistent moments of presence.

A five-minute check-in is a micro-practice for keeping relationships alive. It is intentional but light touch: a brief call, message, or chat that communicates “I see you” and “we still matter.” It requires no agenda, no formal meeting, and no special occasion, only the decision to reach out.

In the EQ-i model, Interpersonal Relationships are defined by mutual satisfaction, compassion, and trust (Stein & Book, 2011). Regular check-ins cultivate all three. They signal reliability, build emotional safety, and prevent the distance that erodes collaboration and closeness.

Steps

Choose one person

Start by identifying one relationship that would benefit from a small act of renewal. This might be a colleague you rely on but have not spoken to lately, a stakeholder whose goodwill is fading, a friend you have lost touch with, or a family member who feels distant. The key is not to overthink. If someone’s name keeps crossing your mind, they are probably the right choice. The goal is to focus on one person at a time so the practice feels personal and achievable. Selecting a single relationship prevents the exercise from becoming another overwhelming task and ensures each connection receives your full attention.

Why: Focus creates intention. Choosing one person channels energy where it counts and stops this practice from dissolving into a vague “I should reach out more.” It turns goodwill into deliberate action.

Reach out briefly

Once you have chosen the person, reach out in a way that feels natural and proportionate to your relationship. It could be a short message, a quick call, or a few words exchanged in passing. Keep your tone light and authentic: “I was just thinking of you—how are things going?” or “It’s been a while since we caught up. How’s your week?” The aim is not to cover everything or fix anything but simply to reconnect. Five minutes is plenty. The strength of the practice lies in frequency, not duration.

Why: Small contact breaks inertia. The act of reaching out bridges emotional distance before it solidifies. It signals care without pressure, showing that connection matters even when time is short.

Listen first

When the other person responds, resist the pull to fill the silence or steer the conversation toward your own updates. Focus entirely on what they are saying. Let them speak freely, and respond with genuine curiosity: “That sounds like it’s been a lot to manage,” or “Tell me more about that.” Listening in this way communicates respect far more deeply than advice or reassurance ever could. You are not solving; you are witnessing.

Why: Being heard is one of the most powerful forms of validation. Active, undivided listening reduces defensiveness and restores trust, reminding others that they are valued beyond their role or output.

Share a small update

After listening, offer a short and sincere glimpse from your side. This could be a piece of personal news, appreciation, or reflection: “I wanted to say how much I appreciated your help on that project,” or “I’ve been experimenting with earlier starts and it’s changed my energy.” Keep it light, real, and proportionate. The goal is to invite reciprocity, not to shift the spotlight.

Why: Relationships thrive on mutuality. Small, appropriate sharing keeps the exchange balanced and human, reinforcing that connection is a two-way act of generosity.

End on appreciation

Close the interaction with a specific expression of thanks or warmth: “I really enjoyed catching up,” or “Thanks for taking the time to talk.” If it feels right, suggest a small next step such as “Let’s do this again soon.” Endings shape memory. Leaving someone with a note of gratitude makes the next conversation easier to begin.

Why: Appreciation strengthens emotional residue. It converts a fleeting exchange into a small but meaningful act of care, reinforcing trust and belonging.

Workplace examples

Cross-team connection: A project manager messages a colleague she rarely sees: “Quick check-in. How is your workload this month?” The short exchange surfaces a shared bottleneck and leads to a joint solution.

Remote leadership: A team leader schedules one five-minute call per day with a different team member. Over a month, morale rises as people feel seen beyond their output and minor snags are solved early.

Personal examples

Friendship maintenance: A friend sends a short text: “Just checking in. How are you doing this week?” The reply arrives within minutes and a coffee date is set without fuss.

Family reconnection: A sibling calls briefly during a walk: “Had a thought about you today. How is your week?” The simple ritual restores warmth that had cooled.

Variations

- Connection habit: Do one five-minute check-in each weekday for two weeks. Track mood and relationship shifts in a simple log.

- Voice notes: Use short voice messages to add warmth and tone without the pressure of a live call.

- Meeting start-ups: Begin team meetings with a one-minute personal check-in round to build group rhythm.

- Appreciation edition: Dedicate one day a week to appreciation only. No requests. Just thanks.

- Boundary-friendly version: If you tend to overrun, set a visible timer and say at the start, “I have five minutes and wanted to say hello.”

Why it matters: Micro-connections compound. Brief, frequent moments of genuine contact increase belonging, engagement, and resilience. In workplaces, regular check-ins create the social fabric that keeps collaboration flexible under pressure. In personal life, they prevent relationships from slipping into the background of busyness.

The deeper truth: Connection thrives on rhythm, not intensity. Five minutes of genuine presence can matter more than an hour of distracted conversation. The check-in is a declaration of care disguised as simplicity. Practised consistently, it turns relationships from background noise into a living network of trust.

3 – Emotional honesty lite

Many people move through conversations half-present, careful with words and cautious with feelings, quietly calculating what is safe to show. It is understandable. Workplaces and even friendships often reward composure over candour. Yet when emotion disappears, so does depth. We may stay polite and efficient, but connection thins out until relationships become purely functional.

Emotional honesty is the practice of letting others see a trace of your inner state. Not the full flood, not forced vulnerability, but a small, deliberate transparency. The “lite” version recognises that emotion does not have to be heavy to be human. By revealing just enough of what you feel, you invite trust, understanding, and repair. It is a discipline of alignment, ensuring that what you say matches what you feel so others can meet the real you rather than the edited one.

Steps

Notice the emotion beneath your surface

Before speaking, pause for a brief emotional check-in. Ask yourself, “What am I actually feeling right now, beneath the task?” It might be mild irritation masked as calm, pride hiding behind modesty, or nervousness disguised as urgency. Take a few slow breaths and name it to yourself: “I am tense,” “I am relieved,” “I am hopeful.” Naming pulls vague sensations into conscious awareness. If the emotion feels layered, write down the first few words that come to mind. This small act of labelling creates emotional literacy and prevents unspoken feelings from hijacking your tone or body language.

Why: What you cannot name, you cannot manage. When emotion remains vague, it leaks sideways through sarcasm, sharpness, or withdrawal. Recognising it early transforms reactivity into choice. It lets you decide what to express, what to contain, and how to align both with intention.

Choose how much to reveal

Emotional honesty does not mean full exposure. It means discernment, finding the amount of truth appropriate to the moment. Before you speak, consider the relationship, context, and purpose. What level of honesty will move the connection forward rather than make it heavy? Sometimes it is a simple tone adjustment: “I felt a little uneasy in that meeting.” Other times, it might be a direct statement: “I was frustrated because expectations were unclear.” The goal is calibration: enough truth to connect, not so much that it overwhelms.

Why: Proportion builds safety. Flooding others with unfiltered emotion shifts the burden to them, while withholding everything creates distance. Calibrated honesty keeps the focus on understanding, not emotional management. It tells others, “I trust you with this, and I am still steady.”

Speak from ownership, not accusation

When you express a feeling, centre it on your experience rather than the other person’s behaviour. “I felt disappointed when the report was late” is very different from “You let me down.” Use “I” statements that connect emotion to context. Avoid moral labels like “right,” “wrong,” or “unprofessional,” which close the door to empathy. Emotional honesty depends less on the words themselves and more on whether your tone carries curiosity instead of judgment.

Why: Ownership invites openness. When emotion is presented as data rather than blame, others can listen without defensiveness. It keeps dialogue anchored in shared learning rather than personal attack.

Link emotion to what you value

Every emotion points to something you care about. Frustration signals blocked purpose; anxiety points to uncertainty; joy reveals alignment. After naming your emotion, articulate the value behind it: “I felt anxious before the presentation because I care about representing our work well,” or “I felt annoyed because reliability matters to me.” This transforms emotion from reaction to revelation, showing others what drives you, not just what agitates you.

Why: Values-based honesty turns feeling into meaning. It helps others see the intention beneath the emotion and strengthens mutual understanding. Over time, it builds a map of what matters to you, which deepens trust and predictability.

Invite reciprocity

After expressing your emotion, pause and open space for the other person: “That is how it was for me. How was it for you?” This small invitation transforms the dynamic from a statement into a conversation. You model emotional literacy and make it safe for others to match your level of candour. Be prepared to listen without rebuttal, even if their response surprises you. The goal is connection, not correction.

Why: Mutual honesty fosters equality. When both sides speak from authentic emotion, power imbalances soften and dialogue becomes cooperative rather than transactional. It rebalances the emotional field of the relationship.

Integrate and close

Once you have spoken and listened, take a moment to settle the exchange. You might say, “Thanks for hearing me. That cleared the air,” or “I feel lighter now that we talked about it.” Integration is what transforms emotional honesty from a moment of exposure into a moment of repair. If appropriate, agree on a small next step that builds on the clarity you have created.

Why: Emotional expression without closure can linger like static. Integration grounds the conversation and turns vulnerability into progress. It communicates maturity and shows that honesty can coexist with steadiness.

Workplace examples

Team friction: A designer says to a project lead, “I felt frustrated when feedback arrived last minute. It made me scramble, and I care about producing my best work.” The conversation leads to earlier reviews rather than resentment.

Manager transparency: Before a big pitch, a leader admits, “I am a bit nervous. I want us to do justice to what we have built.” The admission breaks tension and the team relaxes, sensing shared humanity.

Personal examples

Friendship drift: You tell a friend, “I have missed our regular chats lately. I feel like we have been on different tracks.” The comment opens a candid talk about changing priorities without blame.

Family repair: A sibling says, “I was hurt when you joked about me at dinner. I know you did not mean it badly, but it stuck with me.” The honesty prevents small wounds from festering.

Variations

- Micro-version: Practise expressing one emotion per day in under ten words. Simplicity sharpens courage.

- Value tracing: When strong feelings arise, ask, “What value is this emotion protecting?” Write it down before responding.

- Listening exchange: With a partner, alternate expressing one short emotion-value pair each week (“I felt… because I value…”).

- Written honesty: If saying it feels too risky, begin with a short message or note. The aim is expression, not performance.

- Public honesty: In a team setting, model this lightly: “I am relieved that we are aligned,” or “I am disappointed we missed that deadline, and I want to learn from it.”

Why it matters: Research shows that identifying and articulating emotion reduces physiological stress, improves problem-solving, and increases relational satisfaction (Lieberman et al., 2007; Gross, 2002). But the real significance lies in what follows: emotional honesty bridges empathy and authenticity. It ensures that relationships are not built on guesswork or restraint, but on accurate understanding.

The deeper truth: Emotional honesty is a quiet act of courage. It is not about disclosure; it is about alignment. When your internal world and your external words match, you create integrity. Others can relax because they no longer need to interpret you. Over time, this congruence builds the kind of trust that cannot be demanded or engineered, only earned through truth spoken calmly and without apology.

4 – Reciprocity log

Strong relationships depend on a rhythm of give and take. Yet in professional and personal life, many people drift out of balance. Some over-give to feel needed or in control, while others under-give to protect their independence. Both patterns erode trust over time. True reciprocity means both people feel that their contributions matter, that care, effort, and listening flow in both directions.

A Reciprocity Log helps you observe those flows. It is not about counting favours or keeping score, but about noticing patterns of energy, attention, and support. When you can see those patterns clearly, you can choose to rebalance them, which strengthens mutual respect and sustainability in your relationships.

Steps

Observe your giving

Over several days, pay quiet attention to how you give. This might include time, advice, encouragement, feedback, or simple emotional presence. Write down a few examples each day: “Helped a colleague prepare for a meeting,” “Listened to a friend’s problem,” “Stayed late to fix an issue.” Do not judge; just record. The goal is to become conscious of how generosity naturally shows up in your behaviour.

Why: Awareness begins with observation. Most people overestimate or underestimate how much they give. By writing it down, you turn vague impressions into data. This helps you see whether your support comes from genuine care or from habit, duty, or the need for approval.

Notice your receiving

For the same period, track the support, kindness, or attention you receive. It might be someone sharing insight, offering help, checking in, or giving appreciation. Record these moments without minimising them. Notice how you respond: do you accept easily, deflect, or downplay it? Receiving well is as relationally important as giving.

Why: Many people are uncomfortable being on the receiving end. They rush to return the favour or dismiss the help. Yet accepting support with gratitude is a gift in itself; it allows others to contribute. When you receive openly, you signal trust and equality.

Reflect on the balance

After a week, review your notes. Look for themes. Are you consistently in the role of helper or listener? Do certain relationships feel one-sided? Are there people who give generously to you while you rarely initiate? Note where you feel energised and where you feel depleted. Healthy reciprocity feels alive, not transactional.

Why: Reflection turns information into insight. Imbalance is not always about quantity; sometimes it is about emotional availability. You might realise that you offer advice freely but rarely reveal your own challenges, which can keep others at a distance. Balance is about exchange, not symmetry.

Choose one relationship to rebalance

Pick one person where the flow feels uneven. If you tend to over-give, practise restraint and invite their contribution: “I would value your view on this,” or “Could you take the lead this time?” If you tend to under-give, find a genuine way to offer help or recognition: “I appreciated your input — can I return the favour somehow?” Start with one small adjustment and observe the effect.

Why: Change begins in micro-moments. Shifting one relational pattern has ripple effects. It often surprises people how quickly others respond to small invitations for mutuality once they sense the space is safe.

Express gratitude for both directions

Close your reflection by acknowledging a few people who either supported you or allowed you to support them. You might send a short message or mention it in conversation: “I appreciated how you helped me think that through,” or “It meant a lot that you trusted me with that.” Expressing gratitude consolidates the cycle of giving and receiving.

Why: Gratitude reinforces awareness. When you name what you appreciate, you strengthen that dynamic and remind yourself that generosity and receptivity are both vital forms of connection.

Workplace examples

Over-giver awareness: A team leader realises that she constantly solves others’ problems, leaving little room for colleagues to contribute. She begins to ask, “What do you think would work best?” instead of offering solutions immediately. The shift builds confidence and collaboration.

Under-giver correction: A technical expert notices that he relies heavily on a peer’s advice but rarely acknowledges it. He starts expressing thanks in team meetings and offers reciprocal help in another area. The relationship quickly becomes more balanced.

Personal examples

Family reciprocity: A parent who often supports their adult children starts asking for their perspectives on decisions. This signals respect for their wisdom and deepens mutual maturity.

Friendship repair: Someone who always listens but rarely shares begins opening up about their own challenges. The friendship becomes less about counselling and more about connection.

Variations

- Energy ledger: Instead of counting acts, rate each day’s relational energy as “gave more,” “received more,” or “balanced.” Patterns will emerge over time.

- Gratitude reflection: End each week by writing one sentence of appreciation for something you received.

- Generosity challenge: Once a month, offer support where it is not expected or visible, such as mentoring someone quietly.

- Receiving challenge: Once a week, accept help without deflection or apology.

- Team reciprocity map: In a group setting, have members share one way they supported someone and one way they were supported. It normalises interdependence.

Why it matters: Reciprocity is the circulatory system of trust. Without it, relationships lose oxygen. Over-givers burn out, and under-givers lose credibility. Research on social exchange theory shows that perceived fairness and mutuality are key predictors of satisfaction and commitment in both work and personal settings (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Practising awareness and rebalancing through a Reciprocity Log sustains connection without exhaustion.

The deeper truth: Giving and receiving are not opposites; they are two expressions of belonging. When you give freely but also allow yourself to receive, you communicate equality, humility, and respect. You stop performing strength and start participating in humanity. Over time, this balance creates relationships that are generous, alive, and sustainable, the kind that nourish rather than drain.

5 – Repair conversation

Even the strongest relationships fracture at times. Words are misread, expectations collide, tempers flare, or silence replaces dialogue. What matters most is not the absence of rupture but the ability to repair it. Repair conversations are deliberate acts of reconnection. They acknowledge that something went wrong without turning it into a battle of blame.

Most people either avoid such conversations, hoping time will fix what discomfort cannot, or they rush into them defensively, eager to prove their point. Both paths leave residue. True repair is slower and more conscious. It requires humility, empathy, and emotional regulation, qualities that allow both people to step back from who is right toward what restores trust.

A repair conversation is not about rewriting the past. It is about reopening the channel of goodwill so the relationship can breathe again.

Steps

Acknowledge the rupture

Begin by naming that something between you feels unsettled. Use clear, simple language: “I feel that our last exchange left some tension between us,” or “It seems we have not been in sync lately.” The goal is not to assign fault but to make the disconnection visible. Avoid “you always” or “you never” statements. Focus on what you have noticed and how you feel. Sometimes even acknowledging awkwardness breaks the ice: “This feels a bit uncomfortable to raise, but I think it is worth talking about.”

Why: Denial keeps tension alive. When tension is unspoken, it grows into distance or resentment. Naming the rupture calmly signals maturity and courage. It tells the other person that you value the relationship more than your comfort.

Take responsibility for your part

Before discussing what the other person did, identify your own contribution to the situation. This could be a tone, an assumption, a delay, or a lack of clarity. Express it first: “I realise I may have sounded dismissive,” or “I see now that I did not share enough context.” Taking responsibility does not mean taking full blame; it means owning your influence on the dynamic.

Why: Self-responsibility lowers defensiveness. When you start by acknowledging your own part, you create safety for the other person to reflect too. It models accountability and shows that you are not entering the conversation to win but to heal.

Name the impact, not the intent

Describe how the situation affected you without assuming motives. “When you interrupted me in front of the client, I felt undermined,” is different from “You were trying to make me look bad.” Speak about the impact on your emotions, trust, or ability to work together. Intent can be debated; impact cannot.

Why: Impact-based language prevents escalation. It moves the conversation from accusation to information. It invites empathy by giving the other person access to your experience rather than to your judgment.

Listen for their perspective

Once you have spoken, pause and listen. Ask, “How was this for you?” or “What did you experience?” Let them speak without interruption. This is often the most difficult step because it requires holding space for discomfort without defending yourself. Stay curious. Reflect back what you heard to confirm understanding.

Why: Listening repairs dignity. Even if you disagree, allowing the other person to tell their story rehumanises the interaction. It dissolves the emotional distance that caused the rupture in the first place.

Seek understanding, not victory

Shift from competing narratives toward shared sense-making. Look for overlap: “We both wanted the project to succeed,” or “We both care about fairness.” Where possible, name what you now understand better: “I see why that moment felt disrespectful to you.” Agreement is not the goal; understanding is.

Why: Understanding changes the emotional climate. When both people feel seen and heard, the nervous system relaxes. Only then can genuine repair occur.

Agree on one future behaviour

Close by identifying a small, forward-looking action. “Next time, let us clarify roles before the meeting,” or “If something feels off, let us address it quickly.” Keep it simple and practical. This step converts insight into new relational practice.

Why: Repair without change risks repetition. By translating learning into action, you signal that trust is being rebuilt not just with words but with evidence.

Workplace examples

Team tension: Two colleagues clash over project ownership. One initiates repair: “I think our last discussion left us both frustrated. I realise I was pushing hard on timelines. I value your input and want to align better.” The conversation ends with clearer roles and mutual respect.

Manager-employee conflict: A manager apologises for a harsh tone: “I see now that my feedback sounded personal. That was not my intent. I care about your development and want us to communicate openly.” The admission restores trust faster than justification ever could.

Personal examples

Family misunderstanding: After a heated conversation, one sibling says, “I felt hurt when you cut me off yesterday. I know I raised my voice too. Can we try again?” The other sibling, disarmed by the tone, admits they also felt overwhelmed. The dialogue resets the relationship.

Friendship distance: A friend notices weeks of silence and reaches out: “I sense something changed between us. I miss how easy things were. Did I do something that upset you?” The honesty turns awkwardness into reconnection.

Variations

- Written repair: If speaking feels too tense, begin with a message or letter expressing reflection and care. It can open the door for later dialogue.

- Micro-repair: Use simple phrases to address small ruptures early: “That comment did not land well for me,” or “Can we rewind for a moment?”

- Third-party reflection: Before initiating a major repair, talk with a neutral person to clarify your emotions and avoid rehearsed blame.

- Team reset: In groups, normalise repair by debriefing tense meetings together: “What worked? What felt off? What can we do differently next time?”

- Silent repair: When words are not yet possible, small gestures like a kind message or an offer of help can begin the healing process.

Why it matters: Conflict avoidance corrodes trust faster than conflict itself. Research on relationship maintenance (Gottman, 1999; Holmes, 2002) shows that successful teams and couples are not those without tension but those that repair quickly and respectfully. Repair conversations restore psychological safety and preserve the emotional equity built over time. In organisational contexts, they prevent chronic resentment, miscommunication, and disengagement.

The deeper truth: Repair is not about erasing pain. It is about choosing connection over pride. Every relationship has moments when trust wobbles. What defines maturity is how quickly we move from self-protection to re-engagement. When you practise repair, you declare that the relationship matters more than the story of who was right. In that choice lies the real work of emotional intelligence: to stay open, even after being hurt.

6 – Sharing gifts

Relationships thrive when people feel recognised not only for what they need but for what they bring. Too often, connection focuses on problems, gaps, or expectations: what is missing, what should change, what went wrong. Over time, this creates a subtle imbalance, as if the relationship is built around fixing or accommodating each other rather than valuing what is already present.

Peter Block writes that community is built through the act of sharing gifts, the talents, qualities, and experiences each person contributes to the relationship. When we name and exchange these gifts, we create a foundation of appreciation and equality. This exercise invites you to identify and voice those gifts in your key relationships, deepening respect and mutual confidence.

The practice of sharing gifts does not require grand gestures. It begins with small acknowledgements: noticing a strength, articulating appreciation, or expressing how someone’s presence enriches your life or work. Over time, these exchanges shift relationships from transactional to transformational.

Steps

Reflect on your own gifts

Begin by taking quiet time to identify three or four qualities or skills you bring to relationships. Consider not only your professional strengths but also the ways you contribute emotionally or socially: humour, reliability, calmness, creativity, perspective, kindness, curiosity, or courage. Think about what others often thank you for or rely on you to provide. Write them down, and be honest about what feels most natural to you rather than what you think you should offer.

Why: You cannot share what you do not recognise. Many people undervalue their natural contributions because they come easily. Naming them helps you see your presence as a gift rather than a duty and strengthens your sense of worth in connection.

Notice the gifts of others

Think about two or three people who matter in your daily life or work. For each, identify what you genuinely appreciate or depend on. It might be insight, empathy, humour, discipline, or steadiness under pressure. Focus on what they bring that enhances the relationship, not simply what they do for you.

Why: Relationships deepen when we move beyond evaluation toward appreciation. Seeing others through the lens of contribution changes how you interact with them. It builds respect and shifts attention from deficiencies to assets.

Name and share the gifts

Choose one relationship and express your recognition directly. You might say, “I value how you bring calm to tense situations,” or “Your honesty always helps me see things more clearly.” Keep it short, specific, and sincere. If it feels awkward, remember that naming strengths is an act of courage in a culture that often emphasises criticism over appreciation.

Why: Speaking appreciation aloud activates connection. Research on positive psychology shows that gratitude and strength recognition strengthen bonds and trust. When people hear how they contribute, they feel seen, which increases engagement and reciprocity.

Invite their perspective

After sharing your appreciation, invite the other person to reflect on what they see as their own gifts or what they appreciate in you. You might ask, “What do you think you bring to our partnership?” or “What do you appreciate about how we work together?” Listen without deflecting or modesty. This turns the conversation into a true exchange rather than a one-way compliment.

Why: Mutual sharing creates balance. It prevents the interaction from becoming performative and reinforces equality. When both sides speak about their contributions, the relationship gains mutual awareness and strength.

Integrate the gifts into collaboration

Finally, look for ways to consciously build on these recognised gifts in your interactions. If one of you brings structure and the other brings creativity, plan how those strengths can complement each other in future projects or conversations. Let shared awareness guide how you divide work, make decisions, or support each other.

Why: Recognition without application fades. When gifts are integrated into collaboration, appreciation turns into alignment. This helps both people operate from their strengths, reducing friction and increasing trust.

Workplace examples

Team partnership: A project manager tells a colleague, “I really value your steadiness. When things get chaotic, you bring calm that helps the team focus.” The colleague responds, “And I appreciate your clarity when we are under pressure.” The conversation shifts their partnership from functional to appreciative.

Leader and team: A manager opens a team meeting by naming each person’s distinct contribution: “Maya, your creativity keeps our ideas fresh. Leo, your follow-through makes sure those ideas succeed.” The team feels seen and begins to acknowledge each other’s strengths in turn.

Personal examples

Family connection: A parent tells their teenager, “I love how you bring humour into our home, even when things feel heavy.” The teenager smiles and replies, “And I like that you always listen when I need to vent.” The exchange deepens emotional safety.

Friendship renewal: Two friends who have drifted apart reconnect over coffee. One says, “You have always had a way of helping me see what really matters. I have missed that.” The simple naming reopens a sense of warmth and belonging.

Variations

- Gift circle: In a group or team, invite everyone to name one gift they bring and one they see in another person. It creates an atmosphere of recognition.

- Written reflection: Send a short note or email naming one gift you value in someone. Written words carry lasting weight.

- Reciprocal check-in: Pair with a colleague and spend two minutes each naming what you appreciate about the other’s contribution.

- Personal journal: Keep a running list of gifts you notice in people around you. Review it when relationships feel strained to reconnect with gratitude.

- Start-of-meeting ritual: Begin team meetings with one brief appreciation to reinforce a culture of acknowledgment.

Why it matters: Recognition fuels connection. When people know that their unique qualities are seen and valued, they feel safe to contribute fully. Research on relational appreciation shows that consistent, genuine acknowledgment increases motivation and collaboration (Algoe et al., 2008). In teams, this practice improves trust and resilience. In personal life, it nurtures emotional intimacy and belonging. Sharing gifts turns relationships from a focus on exchange into one of celebration.

The deeper truth: Sharing gifts is not about flattery or performance. It is about naming what is already true. Every relationship is a meeting of strengths, yet most of those strengths remain unspoken. When you voice them, you transform ordinary connection into mutual respect. You remind each other that value flows in both directions, and that being seen for who we are is one of the deepest human needs. In the end, sharing gifts is not just an act of kindness; it is an act of recognition that says, “We both matter here.”

7 – Relational patterns reflection

Relationships are shaped as much by our internal patterns as by the dynamics between people. The ways we connect, withdraw, pursue, protect, or disclose often develop long before the relationships in which they play out. These patterns influence how close we allow ourselves to be, how we respond to tension, how we interpret others’ behaviour, and how much of ourselves we bring into connection. When they remain unexamined, they can create friction, misunderstanding, or emotional imbalance, even in relationships we value deeply.

Relational patterns reflection invites you to look inward before looking outward. Instead of trying to fix the relationship or the other person, this practice focuses on increasing awareness of your own habitual responses. It begins with noticing how you tend to show up: where you lean in, where you hold back, where you over-give, and where you protect yourself. By naming these patterns, you create space between impulse and action, allowing for more intentional connection.

This is not about blame or self-criticism. It is about understanding the templates that guide your relational behaviour so you can make conscious choices rather than default ones. When you know your patterns, you can recognise when they serve the relationship and when they interfere with it. Over time, this reflective capacity deepens emotional maturity, strengthens independence, and enriches the quality of your connection with others.

Steps

1 – Identify your relational signature

Begin by reflecting on the patterns that tend to appear across your relationships at work or in life. Notice whether you:

-

pursue closeness quickly or take a long time to trust

-

avoid conflict or move toward it

-

over-function (fix, soothe, take responsibility) or under-function (withdraw, minimise effort)

-

rely on humour, silence, intensity, or caretaking as relational strategies

Write down the two or three patterns you recognise most clearly.

Why: Every person has a relational signature: a set of predictable ways they move toward or away from others. Identifying this signature reduces blind spots and helps you understand the emotional habits you bring to connection.

2 – Notice your relational triggers

Think about the situations that activate these patterns most strongly. It may be ambiguity, criticism, power differences, time pressure, or emotional exposure. Describe one or two recent moments when you slipped into an automatic pattern and note what triggered it.

Why: Patterns do not appear randomly. They surface in response to internal cues or environmental pressures. Naming these triggers helps you anticipate when you are likely to react rather than respond.

3 – Explore the protective purpose

Every relational pattern, even the unhelpful ones, exists to protect something: your sense of worth, your need for safety, your desire for approval, or your fear of rejection. Gently ask yourself, “What is this pattern trying to protect?” Write your answer without judgement.

Why: Understanding the protective function invites compassion rather than frustration. When you see the intention behind the pattern, you can work with it rather than fight it.

4 – Identify one shift that would improve connection

Looking at the pattern and its trigger, choose one small behavioural shift that would strengthen a key relationship. It may be pausing before withdrawing, asking a clarifying question instead of assuming, or expressing one feeling rather than suppressing it. Keep the shift small and specific.

Why: Awareness becomes powerful when it leads to choice. A small, intentional change can alter the entire emotional tone of a relationship without requiring dramatic action.

5 – Revisit the relationship with awareness

Think of someone who matters to you. Reflect on how your pattern shows up with them. Before your next interaction, take a moment to recall the shift you identified. Enter the conversation with intention rather than habit and observe how the interaction changes.

Why: Reflective insight becomes relational impact when it is applied in real connection. Practising awareness in one relationship helps you develop relational maturity that transfers to others.

Examples

Team collaboration: A leader notices they tend to take over tasks when the team feels stressed. Through reflection, they realise this pattern is driven by a desire to stay useful. Their shift is to pause and ask, “How can I support without taking the work away?” Team ownership strengthens as a result.

Conflict avoidance: A manager recognises that they withdraw during tension to avoid saying something they regret. The shift becomes naming one honest observation early in the conversation. The discussion becomes more open and less charged.

Over-sharing: A colleague realises they disclose too quickly in an attempt to build closeness. Their shift is to slow down and let trust build gradually. Relationships feel steadier and more reciprocal.

Family pattern: Someone notices they intervene quickly in family disagreements to keep the peace. The shift becomes allowing ten seconds before speaking. The family learns to solve more issues without rescue.

Friendship dynamics: A person realises they often expect friends to initiate plans. The shift becomes sending one invitation each month. Friendships deepen with shared effort.

Variations

-

Timeline reflection: Map your relational pattern across three significant relationships from different life stages. Notice what stayed constant.

-

Pattern spotting: Keep a two-week log noting when your pattern appears. Look for trends.

-

Trigger mapping: List five contexts where you feel most reactive. These often reveal the core relational trigger.

-

Strength reflection: Identify how your pattern also functions as a strength (e.g., sensitivity, independence, loyalty).

-

Pre-conversation pause: Before a difficult interaction, name your likely pattern and choose an alternative response.

Why it matters: Relational self-awareness is one of the strongest predictors of healthy, balanced interpersonal relationships. When leaders understand their own patterns, they reduce emotional reactivity, communicate more clearly, and create space for others to be themselves. Research on attachment and interpersonal effectiveness shows that self-reflection increases trust, reduces misinterpretation, and supports healthier boundary-setting. It also prevents relational overuse, such as over-sharing or over-involvement, and underuse, such as emotional detachment.

By noticing and naming your patterns, you strengthen the balancing factors of independence, problem solving, and self actualisation. You become more deliberate, less driven by old scripts, and more able to create relationships that feel mutual, respectful, and grounded.

The deeper truth: Relational maturity begins with knowing the shape of your own heart. When you understand the habits that protect you, you can choose when to soften, when to step forward, when to hold back, and when to let go. You become less ruled by past patterns and more guided by present intention.

Over time, relational patterns reflection transforms how you show up. You stop repeating old relational scripts and begin writing new ones. You connect with others not from habit, but from awareness. And in that shift, you offer something profound: a version of yourself that is both more authentic and more free.

8 – Micro-acknowledgements

Relationships are sustained not only by meaningful conversations or deep moments of connection but by the small, steady signals that say, “I see you,” “I value you,” and “You matter here.” These micro-acknowledgements often pass unnoticed because of their simplicity. A nod of appreciation, a short thank you, or a brief recognition of someone’s effort may last only a few seconds, yet these moments accumulate into a powerful relational foundation.

Human beings attune to micro-signals more than we realise. In social psychology, these are known as “relational bids,” the tiny cues people offer in the hope of being recognised or valued. When these bids are noticed and met, trust deepens. When they are missed, dismissed, or overshadowed by stress, relationships subtly weaken over time. Micro-acknowledgements are a deliberate practice of meeting these relational bids with presence and appreciation.

Unlike formal recognition or gratitude rituals, micro-acknowledgements are light-touch, frequent, and grounded in the everyday. They do not require preparation, emotional intensity, or long conversations. They simply require noticing: noticing effort, noticing contribution, noticing someone’s emotional state, or noticing that a person has made your day easier in a way they may not even realise. This noticing communicates respect and relational warmth in a culture that often prioritises speed over connection.

Over time, micro-acknowledgements protect relationships from erosion, misunderstandings, and emotional distance. They keep connection alive during busy seasons and strengthen a sense of belonging without grand gestures or dramatic interventions.

Steps

1 – Practise noticing small contributions

Spend a day paying attention to small acts around you: a colleague who anticipates a need, someone who shows patience in a difficult meeting, a teammate who takes extra care in communication, or a friend who reaches out even briefly. Write down at least three of these moments at the end of the day.

Why: Awareness precedes acknowledgement. When you slow down enough to notice everyday contributions, your relational lens widens. This trains your mind to see value not just in outcomes but in effort, intention, and presence.

2 – Offer a one-sentence acknowledgement

Choose one moment you noticed and speak a simple, direct acknowledgement to the person involved. Keep it short, grounded, and specific. You might say, “Thanks for the clarity you brought to that discussion,” or “I appreciated how you checked in with the team this morning.” Avoid flourish or embellishment. Sincerity is the core.

Why: Short acknowledgements land more easily because they do not require emotional preparation on either side. Research on micro-affirmations shows that small signals of recognition have disproportionate positive impact on motivation and trust.

3 – Name the effect, not just the action

Extend your acknowledgement with one phrase that names why it mattered. “That helped me refocus,” “It made the task smoother,” or “It lifted the mood in the room.” This frames the action in terms of meaningful impact rather than politeness.

Why: Naming impact strengthens relational awareness. People often underestimate the effect of their behaviour. Hearing the difference they made reinforces confidence and reciprocity.

4 – Look for emotional cues, not only performance cues

Micro-acknowledgements are not only for visible actions. They can also respond to emotional effort, such as someone staying calm during tension, showing courage in a meeting, or offering kindness when it was not required. Acknowledge the emotional dimension when you see it: “I noticed how steady you stayed during that conversation. It helped all of us.”

Why: Emotional labour is often invisible and unrecognised. Naming it validates the deeper work that enables teams and relationships to function under pressure.

5 – Build a daily or weekly rhythm

Choose a rhythm that works for you: one micro-acknowledgement every day, three per week, or one per meeting. Keep it intentionally low-stakes. Over time, this becomes a relational habit rather than a task.

Why: Consistency creates cumulative strength. Small signals, repeated over time, generate more trust than occasional grand gestures.

Examples

Team environment: A team member says, “Thanks for the way you summarised our discussion. It helped us land quickly.” The moment takes five seconds, yet the colleague feels their contribution was seen, increasing motivation.

Leadership presence: A leader pauses after a demanding meeting and quietly tells someone, “I appreciated your calmness. It kept the conversation constructive.” This reinforces emotional maturity as a valued contribution.

Remote collaboration: During a virtual call, a manager acknowledges, “I noticed you had the documents ready ahead of time. It made this discussion much smoother.” The comment strengthens connection across distance.

Family: A partner says, “I saw how patiently you handled that stressful moment. It helped us stay centred.” The brief acknowledgement nurtures emotional safety.

Friendship: A friend texts, “Thanks for checking in today. It meant a lot.” The micro-gesture keeps the friendship warm even in busy seasons.

Variations

-

Three-minute practice: At the end of each day, reflect for three minutes on micro-contributions you noticed. Choose one to acknowledge the next day.

-

Silent noticing: Even when you do not voice the acknowledgement, practise mentally naming the contribution. This increases your relational sensitivity.

-

Meeting opener: Start meetings with one sentence of appreciation directed at the group or an individual.

-

Written micro-notes: Use a simple one-line message or email. Written micro-acknowledgements often have lasting effect.

-

Emotional focus day: Dedicate one day to noticing emotional contributions such as kindness, patience, or restraint.

Why it matters: Micro-acknowledgements build relational stability by reinforcing psychological safety and belonging. They counteract the tendency to notice only what is missing or what creates friction. Research in relational neuroscience shows that small positive signals strengthen trust, increase oxytocin, and create a sense of visibility and validation. In teams, they improve engagement and reduce the emotional cost of collaboration.

Unlike large recognition efforts, micro-acknowledgements are sustainable. They weave appreciation into the texture of everyday life, preventing relationships from drifting into indifference or transactional patterns. Over time, these micro-moments create a shared emotional memory that makes relationships resilient during stress and uncertainty.

The deeper truth: Connection is maintained not by extraordinary moments but by ordinary ones, repeated with care. Micro-acknowledgements teach us that being seen does not require dramatic gestures. It requires noticing, presence, and the willingness to speak a simple truth: “You made a difference today.” These small acts hold relationships together in a world that moves too fast to celebrate the quiet contributions that matter most.

In the end, micro-acknowledgements are less about praise and more about recognition of humanity. They remind us that we are shaped by the signals we give and receive, and that even the smallest moment of presence can strengthen the relational threads that help us feel part of something larger.

Conclusion: Belonging with intention

Interpersonal relationships are not simply a by-product of working or living together. They are a daily practice of noticing, appreciating, and repairing. The six exercises in this article are not social niceties but pathways into presence. Each one strengthens a different muscle of connection: awareness of who matters, honesty about how we relate, gratitude for what we receive, and courage to repair what has been strained.

This matters because disconnection is costly. When relationships drift, collaboration becomes mechanical, and care fades into politeness. When trust breaks and remains unaddressed, teams lose their spark and individuals lose their sense of belonging. At the other extreme, when relationships blur into over-dependence, boundaries weaken and fatigue follows. Healthy relationships balance openness with autonomy, giving and receiving in equal measure.

Interpersonal skill sits at the centre of emotional intelligence because it makes every other skill visible. Empathy without relationship is sympathy from a distance. Self-regard without relationship risks isolation. Social responsibility without relationship becomes duty without warmth. Connection is where emotional intelligence takes form, where understanding turns into care, and care turns into trust.

The practices outlined here are deliberately varied. The Relationship Audit builds awareness of your social landscape. The Five-Minute Check-In restores connection through brief but intentional presence. Emotional Honesty Lite cultivates openness without oversharing. The Reciprocity Log helps balance giving and receiving. The Repair Conversation restores trust when it has been tested. And Sharing Gifts renews appreciation and belonging. Together, they form a rhythm of relational care: awareness, honesty, balance, repair, and appreciation.

Interpersonal relationships are not about being liked by everyone. They are about showing up with integrity, curiosity, and compassion. They remind us that influence without connection is hollow, and that productivity without trust is brittle. To belong with intention is to choose presence over convenience, appreciation over assumption, and repair over resentment. It is how emotional intelligence becomes visible in everyday life.

Reflective questions

- Which of your relationships feel most alive and which feel most neglected? What does that reveal about your patterns of attention?

- How do you tend to respond when trust is strained? Do you withdraw, confront, or repair?

- In your daily routines, where could you make small shifts to increase real connection, not just communication?

- How balanced is your pattern of giving and receiving support? What might it look like to restore equilibrium?

- If you were to name the three people who most sustain your energy and purpose, how could you show them appreciation this week?

Interpersonal relationships are not about collecting contacts but cultivating connection. They are the soil in which trust, collaboration, and wellbeing grow. When you treat relationships as living systems that need tending, you create the conditions for both success and humanity to flourish.

Do you have any tips or advice on raising interpersonal relationships?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Interpersonal Relationships is one of the three facets of Interpersonal realm that also includes Empathy and Social Responsibility.

References

Algoe, S.B., Haidt, J. and Gable, S.L. (2008) ‘Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life’, Emotion, 8(3), pp. 425–429.

Bar-On, R. (1997) BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) Technical Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Block, P. (2018) Community: The Structure of Belonging. 2nd edn. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Cacioppo, J.T. and Patrick, W. (2008) Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. New York: W.W. Norton.

Dutton, J.E. and Heaphy, E.D. (2003) ‘The power of high-quality connections’, in Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E. and Quinn, R.E. (eds.) Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, pp. 263–278.

Fredrickson, B.L. (2001) ‘The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions’, American Psychologist, 56(3), pp. 218–226.

Gottman, J. and Silver, N. (1999) The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. New York: Crown.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B. and Layton, J.B. (2010) ‘Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review’, PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Kahn, W.A. (1993) ‘Caring for the caregivers: Patterns of organizational caregiving’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(4), pp. 539–563.

Seligman, M.E.P. (2011) Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York: Free Press.

Stein, S.J. and Book, H.E. (2006) The EQ Edge: Emotional Intelligence and Your Success. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons Canada.

Leave A Comment