There is a particular unease that comes from hearing a leader agree with you in private and then watching their commitment thin out the moment peers begin to speak. You can feel the shift instantly: the firm nod becomes a softer one, the language moves from “let’s do it” to “let’s explore”, and the idea you thought you were carrying together suddenly becomes yours alone. It is tempting in moments like this to assume that the leader is inconsistent or overly impressionable. Yet the more we look at what behavioural research tells us, the more this interpretation misses the deeper mechanics at play.

People at every level of an organisation are shaped by their context, and senior leaders perhaps most of all. They do not sit above the system. They sit inside multiple systems simultaneously: social, political, emotional and reputational. Each of these systems exerts a pull on their choices. One of the most powerful forces is social conformity. Decades of research, beginning with Solomon Asch’s now well-known experiments, show that individuals will alter their stated views simply to remain aligned with a group, even when the group is clearly mistaken. In leadership settings, where relationships are long-standing and the currency is credibility rather than accuracy, this force is magnified. What looks like a change of mind is often a shift towards maintaining cohesion with a peer group whose ongoing approval matters more in the moment than any single proposal.

Layered onto this is the psychological reality of loss aversion. Humans are disproportionately motivated to avoid loss rather than pursue gain. This is not about money in most workplaces. It is about reputation, conflict and relational cost. A leader may genuinely believe your idea has merit, but when objections surface publicly, those objections represent potential losses: political pushback, friction with a colleague, a future moment where they may need to defend something that makes others uncomfortable. Even if the risk is small, the human brain is calibrated to respond more strongly to potential loss than to potential benefit. What looks like wavering is often a rational attempt to minimise foreseeable discomfort.

Another dynamic at work is pluralistic ignorance, the belief that one’s private view is held by very few, even when in reality it is widely shared. A single forceful objection can create the illusion that the whole room is sceptical. Leaders, especially those who try to keep discussion balanced, may interpret silence as dissent or interpret a vocal minority as a broader sentiment. They step back not because their conviction has dissolved but because they assume they are in the minority, and standing alone feels unwise.

All of this occurs under the weight of cognitive load. Senior leaders carry a significant volume of competing priorities and incomplete information. When the mind is saturated, it relies on heuristics that favour simplicity, harmony and short-term risk reduction. In practice, this means a leader may sincerely commit to an idea in a quiet one-to-one, with the mental space to reflect, and then shift course in a busy meeting where competing issues are jostling for attention. The inconsistency is not a flaw in character. It is the natural effect of a taxed cognitive system that is trying to reduce complexity wherever it can.

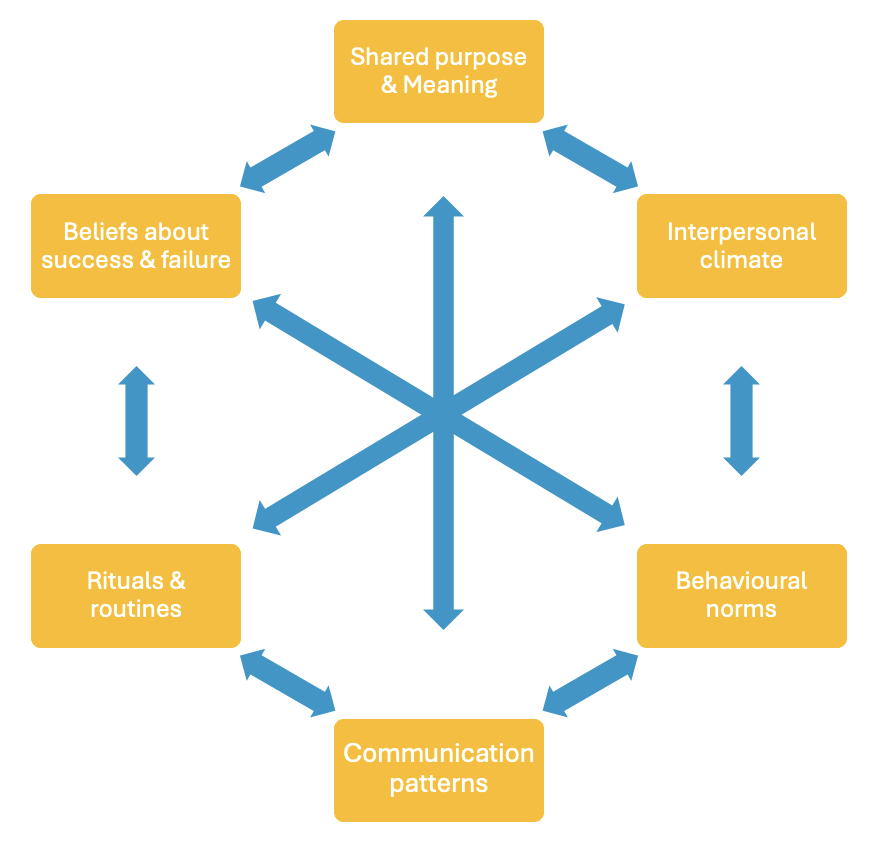

Taken together, these forces create a picture that is far more textured than the simple narrative of “my leader changed their mind”. They reveal an environment in which leaders are constantly reading the room, managing invisible expectations and making micro-judgments about where to place their energy and allegiance. Understanding this allows us to approach influence differently. Instead of trying to harden someone’s commitment or prevent them from being swayed, we can work on shaping the context so that staying steady becomes less costly socially, politically and cognitively. That is where upward influence truly begins.

Strategies for influencing upward

BEFORE THE MEETING

1. Pre-align the people who influence your leader’s sense of risk

The most reliable predictor of a leader shifting position in public is the presence of a confident peer who voices doubt. Social conformity research shows that dissenting opinions carry disproportionate weight when they come from perceived equals, and leaders will often move to align with the loudest or most certain view to maintain relational standing. By meeting with those individuals before the formal discussion, you reduce the emotional hazard for your leader. You are not seeking unanimous agreement. You are simply lowering the temperature so the idea is not introduced into a hostile environment.

Leadership moves:

-

Identify two or three people whose reactions tend to sway your leader.

-

Meet with them quietly, well before any formal discussion.

-

Share your thinking early and ask what concerns they would want addressed.

-

Adjust your proposal in good faith and reflect their input explicitly in the meeting.

This does not guarantee support, but it dramatically reduces the pressure on your leader to protect themselves by stepping back.

2. Build a shared purpose before introducing your recommendation

Behavioural studies show that when people anchor first on purpose rather than the solution, they process information more openly. This is related to anchoring bias and motivated reasoning: once a preferred solution is introduced, others evaluate it through personal interests, departmental priorities, and existing habits. If you create a shared purpose early with your leader, you give them a lens strong enough to withstand competing pressures. In effect, you provide a reference point more compelling than the noise of the moment.

Leadership moves:

-

Meet your leader beforehand and agree on the problem statement and success criteria.

-

Use language that centres on outcomes the leader already values.

-

Position your recommendation as one of several ways to meet that purpose.

-

Ask for agreement on the purpose in writing to solidify the anchor.

This approach creates cognitive stability. Your leader is less likely to shift when the conversation is anchored in shared intention rather than individual preference.

3. Reduce perceived risk by offering a trial, not a sweeping decision

Loss aversion tells us that humans fear loss twice as much as they value equivalent gain. For leaders, “loss” often means conflict, political exposure, or being associated with an idea that later fails. By proposing a limited pilot or trial, you reduce the perceived stakes of supporting you. Psychologically, pilots create a reversible path, which makes it safer to say yes. Culturally, they signal humility and learning rather than unilateral change.

Leadership moves:

-

Frame your recommendation as a small-scale, time-bound trial.

-

Define two or three learning questions the pilot will answer.

-

Specify what data you will bring back to review the decision.

-

Ask your leader only to sponsor the pilot, not the full rollout.

This allows your leader to maintain public support without fearing future consequences. It also reduces the likelihood of backtracking under pressure.

DURING THE MEETING

4. Establish the purpose of the conversation before anyone debates the solution

Group dynamics shift rapidly once solutions are presented. People begin defending positions rather than exploring possibilities. To prevent this, begin by grounding the meeting in the shared purpose you co-created. This aligns with research on framing effects: when a conversation is framed around a collective goal, participants are more likely to seek alignment than to compete for influence. It also signals that you are not pushing an agenda but stewarding a larger interest.

Leadership moves:

-

Open with a simple recap of the purpose and desired outcome.

-

Name the conditions you want to hold the group to, such as curiosity or shared accountability.

-

Invite others to add to or refine the purpose before moving forward.

This creates psychological safety and reduces the chance that your leader will feel pulled away by competing narratives.

5. Neutralise social pressure by bringing quieter supporters into the conversation

Asch’s conformity studies revealed that unanimity, even false unanimity, is incredibly persuasive. However, a single ally, even a modest one, reduces conformity dramatically. In a meeting, this means that if only critics speak, your leader will feel surrounded. If supportive voices speak early, the leader will feel balanced. This is not manipulation. It is creating a more accurate social picture.

Leadership moves:

-

Invite one or two supportive colleagues to contribute early in the discussion.

-

Ask them beforehand to share practical benefits or clarifications.

-

If resistance emerges, reinforce alternative views with calm statements like, “I know some colleagues have found this useful, so perhaps we can hear from them.”

Your leader will be more likely to maintain alignment when they are not isolated. Social pressure becomes social support.

6. Reduce cognitive load by surfacing decisions clearly and simply

Leaders under pressure experience cognitive overload, which leads to risk-averse behaviour and quick shifts in position. When a conversation becomes chaotic or heavy with detail, the leader’s mind reaches for the safest option: delay or retreat. You can counter this by simplifying the decision space. Studies on choice architecture and cognitive load show that people make more stable commitments when options are presented cleanly and the consequences are transparent.

Leadership moves:

-

Summarise the discussion in the moment using calm, neutral language.

-

Offer a small number of well-framed options, such as “Do we want to proceed with the pilot, adjust the scope or pause for more information?”

-

Check whether the leader wants the group to decide now or at a later stage.

This protects your leader from the overwhelm that often triggers sudden reversals.

Wrapping up

Influence at senior levels is rarely a matter of better arguments. It is the cumulative effect of how we prepare the ground, how we read the room and how we place ourselves in relationship with the people who hold formal authority. When a leader shifts position in public, it is tempting to interpret this as a personal slight or a failure of courage. Yet the behavioural science tells a different story. Much of what we label inconsistency is simply human psychology playing out under pressure, amplified by the complexity of organisational life. Once we see the dynamics clearly, we can stop trying to make someone more steadfast than the system allows, and instead work on reshaping the conditions that surround them.

What ultimately steadies a leader’s commitment is not persuasion, insistence or the tactical defence of an idea. It is the presence of shared purpose, the reduction of social risk, the careful engagement of others before tensions arise and the creation of a simpler, less costly path for people to follow. These moves are acts of stewardship. They acknowledge that influence happens in community, not in isolation. They also remind us that our responsibility is not to win every argument, but to bring people together in a way that makes accountability and progress more possible.

At its heart, this is an invitation to shift the story. Instead of focusing on why a leader wavers, we can turn our attention to the ways we might help them stand more comfortably, and to the choices we can make that do not rely on anyone else being braver, louder or more certain. Influence becomes less about convincing and more about creating the environment in which good decisions can take hold.

Three reflective questions

-

Which part of your current approach to influencing upward relies on hoping your leader will behave differently, and what might change if you focused instead on shaping the surrounding conditions?

-

Who needs to be in the conversation before the meeting, not during it, for your next proposal to have a more stable foundation?

-

What level of responsibility are you willing to take for creating clarity, reducing risk and strengthening the social fabric around your ideas?

How can I influence others without manipulating them is another article that may be of interest on the topic of influence

Do you have any tips or advice for raising influence upwards?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Leave A Comment