Bruce Tuckman’s team development model (Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing and Adjourning) has shaped leadership thinking since the 1960s. For decades, it has been treated as the default explanation of how teams develop and mature.

But many leaders now question whether Tuckman’s model still fits modern teams. Work today is more fluid, distributed and interdependent. Teams form and reform quickly, authority is shared, psychological safety and inclusion are central, and change is continuous. In this context, the traditional five-stage sequence often fails to reflect how real teams actually grow, struggle and adapt.

This article explores the limitations of Tuckman’s model for 21st-century teams and introduces a contemporary alternative pattern designed for complexity: Aligning, Belonging, Co Creating, Adapting and Sustaining.

Update January 2026: This article outlines the core “Five Movements” framework. To understand the risks and dysfunctions associated with each movement, read the follow-up article: The Shadow Side of the Five Movements.

Bruce Tuckman’s five-stage model has been a staple of organisational life since the 1960s. Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing and Adjourning offered leaders a reassuring map of how teams were expected to develop. It captured something true for its time: teams were often stable, co located, and given clear, bounded tasks. They typically did pass through phases of orientation, conflict and consolidation before reaching performance. The model became popular not only because of its descriptive accuracy, but because it gave leaders the illusion of control. If teams moved through these stages, leaders could believe that progress was unfolding as it should.

But the organisational context that gave rise to Tuckman’s model has changed. Work today is more dynamic, more distributed, and more interdependent than the world of the 1960s. Many teams do not stay together long enough to move linearly through five tidy stages. People rotate in and out. The work evolves while the team is doing it. Authority is more shared, culture more diverse, communication more hybrid, and expectations more fluid. Modern teams often experience multiple overlapping cycles of clarity, confusion, conflict, learning and reinvention, none of which map neatly onto the original sequence.

Moreover, Tuckman’s model is silent on essential conditions that modern research has brought to the forefront: psychological safety, inclusion, identity, belonging, distributed leadership and continuous learning. These are no longer peripheral concerns; they are central to whether teams can think well together. The presumption that teams “storm” early and then settle is contradicted by experience: teams encounter tensions whenever context shifts, membership changes or uncertainty increases. They revisit these moments regularly, and their success depends less on following a sequence and more on their capacity to create safety, connection and adaptability in real time.

None of this makes Tuckman irrelevant as a piece of history. It simply makes it insufficient. When leaders rely on it as the definitive story of team development, they risk imposing a structure that hides more than it reveals. They can misinterpret normal, healthy team behaviour as failure simply because it does not match the expected order. They can overlook the demands of modern complexity and cling to a model that was built for a different world.

For this reason, it is helpful to explore alternatives. The following is not a replacement or a universal truth. It is offered instead as a possible idea, a contemporary pattern based on what teams seem to need now. It frames team development not as a linear march through fixed stages, but as a set of recurring movements that teams cycle through repeatedly as conditions change. These movements are: Aligning, Belonging, Co Creating, Adapting and Sustaining.

They invite leaders and teams to pay attention not to the order of development, but to the experience and needs of the people doing the work.

A possible 21st century pattern: five developmental movements

Aligning

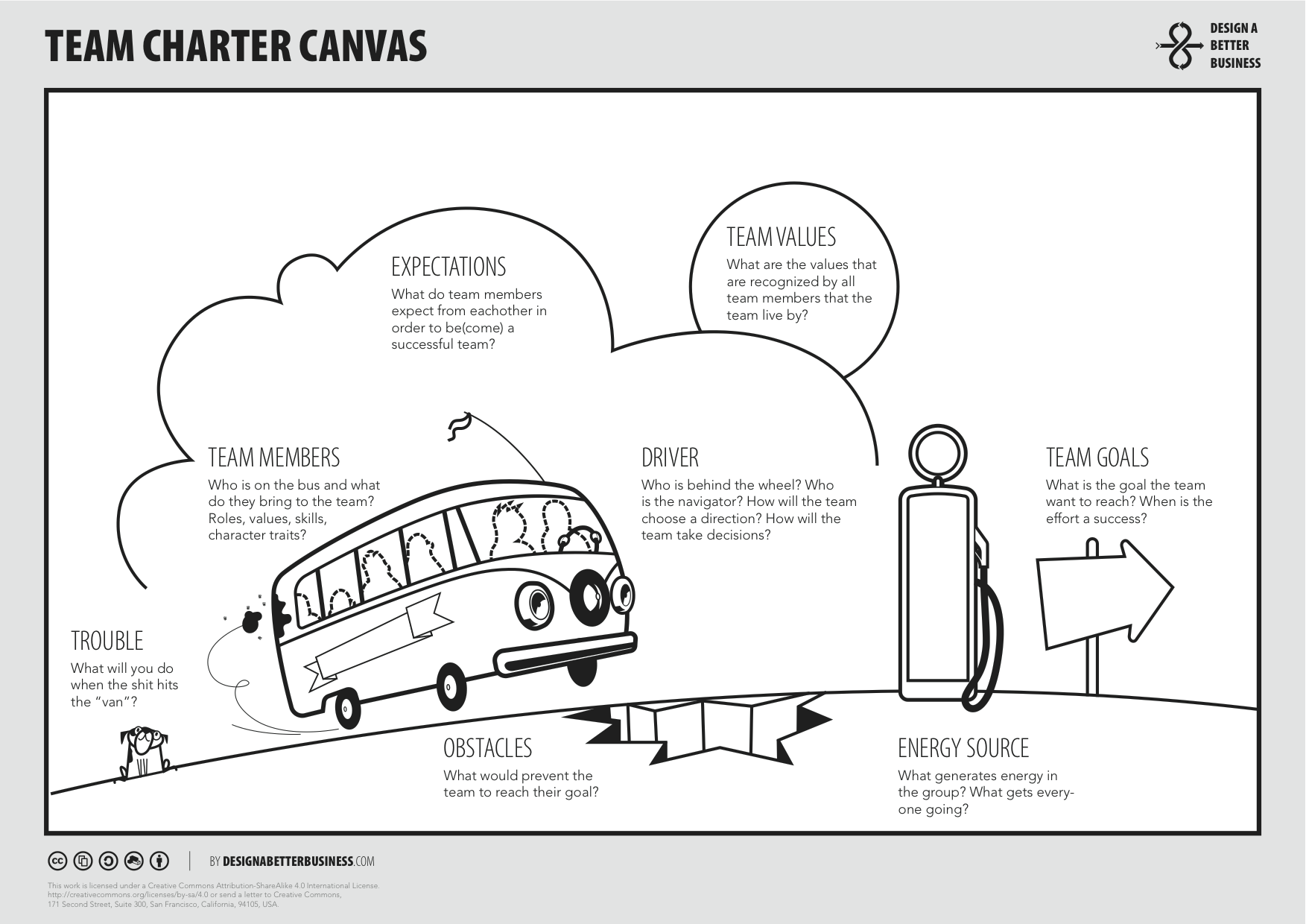

Modern teams rarely begin with certainty. They start with ambiguity, evolving expectations, and stakeholders whose needs may shift even as the work begins. Aligning is the movement where teams create shared purpose, identity,and intention. It goes beyond reviewing project documents; it requires candid discussion of why the team exists, what value it aims to create, and the constraints within which it operates. Without aligning, teams move quickly but not coherently. They leap into activity without agreement on direction, leading to rework, frustration, and conflicting assumptions.

Leadership moves for Aligning

-

Host “Purpose” conversations: Draw out each member’s understanding of the task, then synthesise it into a shared mission the whole team recognises.

-

Surface hidden assumptions: explicitly ask, “What are we taking for granted that we have not yet discussed?”

-

Co-write a working agreement: Capture expectations for communication, responsibilities, decision rights, and boundaries.

-

Re-align regularly: Treat alignment as a compass check, not a one-off event. Revisit purpose whenever context shifts or membership changes.

Belonging

Belonging is the foundation on which all productive collaboration rests. It is not about creating a cosy atmosphere; it is about establishing psychological safety so that people can think aloud, disagree thoughtfully, and bring their full perspective into the work. Where Tuckman positioned conflict early, modern research shows that productive conflict only becomes useful when belonging has been built first. People must feel accepted before they can challenge ideas without it feeling like an attack on their identity.

Leadership moves for Belonging

-

Model vulnerability: Name uncertainty, ask for input, and admit when you do not know to lower the stakes for others.

-

Amplify quiet voices: actively invite contributions from those who may be culturally or temperamentally less likely to interrupt.

-

Distinguish safety from comfort: Remind the team that “safe” means it is safe to speak up, not that every conversation will feel comfortable.

-

Humanise the remote space: Use check-ins to build the relational “connective tissue” that buffers against stress.

Co-Creating

Once a team has built clarity and belonging, it can begin co-creating its ways of working. This movement is dynamic and involves shaping norms together rather than inheriting them. However, for co-creation to produce genuine innovation, it must explicitly include Structured Conflict.

In a desire to preserve the “Belonging” established in the previous movement, many modern teams fall into the trap of “artificial harmony, nodding along to avoid tension. Co-creating resists this by normalising friction. It acknowledges that the best solutions emerge from the collision of different viewpoints. Teams in this movement actively design how they will disagree, ensuring that challenge is viewed as a duty to the work, not a disruption.

Leadership moves for Co-Creating

-

Designate a “Challenger”: Rotate the role of a “devil’s advocate” in meetings to ensure ideas are stress-tested and to authorise dissent.

-

Normalise experimentation: Encourage pilots and learning loops rather than large, rigid plans.

-

Create “Conflict Protocols”: Agree in advance on how the team will handle deadlock or disagreement (e.g., “If we disagree, we run a test,” or “We use ‘fist of five’ voting”).

-

Mine for conflict: When everyone agrees too quickly, ask, “What are we missing? Who sees a risk here?”

Adapting

In the 21st century, performance is not a destination but a capability. Teams that thrive are those that can adapt quickly to change. Adapting involves scanning the environment, noticing emerging challenges, shifting priorities, and redistributing authority as needed.

This differs from Tuckman’s Performing stage, which implied stability. Modern work rarely offers such stability. High-performing teams are those that can reorient themselves repeatedly without losing cohesion. They treat change not as a failure of planning, but as a normal condition of the landscape.

Leadership moves for Adapting

-

Introduce pauses: Create “sense-making” moments whenever new information emerges to recalibrate.

-

Enable distributed leadership: Empower those with the most relevant knowledge, not necessarily the highest rank—to make timely decisions.

-

Frame change as learning: ask, “What is this shift inviting from us?” rather than “Why is this happening to us?”

-

Capture lessons continuously: Conduct “After Action Reviews” mid-stream, not just at the end of projects.

Sustaining

All teams end, transition, or transform. Sustaining is the movement where teams reflect on their journey and manage their resources, specifically, their Energy.

While Tuckman’s Adjourning focused on disbanding, Sustaining acknowledges that 21st-century work is often continuous and “always-on.” Without intentional intervention, teams burn out. Sustaining involves pacing the work, protecting cognitive capacity, and ensuring that the team’s human battery does not run dry. It also involves “Endings”—honouring contributions and capturing knowledge so that when members leave, the team’s intelligence remains.

Leadership moves for Sustaining

-

Manage energy, not just time: Monitor the team for signs of burnout and actively de-prioritise work when capacity is breached.

-

Institutionalise recovery: Mandate “quiet hours” or meeting-free days to allow for deep work and cognitive rest.

-

Facilitate “Retrospectives of Worth”: Identify not just what was achieved, but how the team grew and what practices should be carried forward.

-

Create knowledge bundles: Ensure key decisions and artefacts are documented, so transitions don’t result in amnesia.

These movements are cyclical. Teams may return to aligning when new members join, revisit belonging when trust is strained, or re-enter co creating when tools or expectations shift. What matters is not following a sequence, but cultivating awareness and responsiveness. Modern teams succeed not because they march through five predictable stages, but because they attend to purpose, people, collaboration, learning and stewardship as ongoing, interconnected practices.

Any thoughts on this idea?

Do you have any tips or advice for developing teams in the 21st century?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

A warning: the shadow side

While this pattern offers a more realistic map than Tuckman, it is not a silver bullet. Every model has a risk. Healthy movements can mutate into dysfunction if they are not monitored. Aligning can harden into dogma and Belonging can slip into artificial harmony.

I have explored these specific pitfalls and how to fix them in a companion guide: The Shadow Side of the Five Movements: Diagnosing Team Dysfunction

I recommend reading that next if you are planning to introduce this model to your team.

Leave A Comment