We have all encountered the dynamic. You are in a senior leadership meeting, the stakes are high and a critical issue is on the table. Yet instead of addressing the elephant in the room a colleague deflects. They offer vague agreement, shift the topic or remain silent. Later in the corridor or on a private call the truth finally surfaces, but by then the moment to act has passed.

It is easy to label this behaviour as a lack of courage, professionalism or accountability. However, the data suggests this is not an isolated lack of character but a systemic organisational haemorrhage.

Research by VitalSmarts into the “cost of silence” surveyed over 1,000 leaders and employees. They found that 72 per cent of people fail to speak up when a peer fails to pull their weight or makes a mistake. Furthermore, the study calculated that the average person wastes seven days complaining, doing unnecessary work or ruminating about the problem instead of speaking up. In financial terms they estimated that every failed conversation costs an organisation approximately £5,500 (or $7,500) and over eight hours of lost productivity.

If avoidance is this expensive why is it so common?

Behavioural science suggests that most senior leaders do not avoid difficult conversations because they are incompetent. They avoid them because they are human beings responding to perceived threats, social costs and cognitive biases. The silence is not an accident. It is a rational calculation.

To influence these colleagues we must stop judging their character and start addressing the psychological drivers behind their silence. By understanding why they avoid the conversation you can change the conditions that make silence their default strategy.

1. The risk manager: managing personal safety rather than avoiding responsibility

When a senior colleague skirts a difficult topic they are often performing a rapid and unconscious risk assessment. At senior levels difficult conversations are rarely just about the work. They implicitly question competence, judgement and status. To a leader whose career is built on being the one with the answers, uncertainty does not just feel uncomfortable. It feels dangerous.

Amy Edmondson’s foundational work on psychological safety defines it as “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking” (Edmondson, 1999). When this safety is low the brain processes social friction as a biological threat. Neuroscience shows that social threat activates the same neural pathways as physical pain. The amygdala hijacks the prefrontal cortex, which is the very part of the brain needed for logic and strategy. This creates a cognitive paradox. The more critical the conversation, the less capable their brain becomes of engaging in it. Your colleague is not disengaged. They are protecting their professional identity from the risk of exposure.

The leadership task: Your role is to change the risk equation. You must make it safer to speak than to stay silent.

- Lead with bounded fallibility: Open the conversation by admitting your own uncertainty. Phrases like “There may be things I am missing here” or “I want your honest assessment even if it challenges my view” signal that the conversation is about joint problem solving rather than performance evaluation.

- Separate identity from impact: Explicitly state that the discussion is about outcomes rather than character. Try saying “Your judgement is not in question. I want to examine the impact of this specific decision.”

The core shift: When a colleague avoids a difficult conversation ask not “Why are they being resistant?” Ask “What interpersonal risk do they believe they are managing?”

2. The pragmatist: learned futility and the efficiency of silence

Some colleagues do not avoid conversations because they feel unsafe. They avoid them because they believe they are pointless.

This is learned futility. It is a behaviour rooted in energy conservation. Senior leaders operate under immense cognitive load and they must decide where to invest their limited political and emotional capital. If a leader has repeatedly seen that candour leads to no action or acknowledgement then silence becomes a rational efficiency strategy. Morrison and Milliken (2000) described “organisational silence” not as a lack of ideas but as a response to systems that signal voice is unwelcome or wasted. This is the extinction principle of behavioural psychology. When an action stops producing a result the organism eventually stops performing the action. They are not resisting you. They are running a return on investment calculation on their own energy.

The leadership task: Your role is not to ask better questions but to demonstrate that voice has consequences.

- Close loops publicly: If you ask for candour you must show where it went. Even if you cannot act on their input explain why. Silence after feedback confirms their suspicion that speaking up was a waste of time.

- Make micro impact visible: Reference their input in later decisions. Tell them “We adjusted this timeline based on the concern you raised last week.” When people see their voice leaves a mark on the work the efficiency calculation changes.

The core shift: Ask not “Why do they not care?” Ask “What has their experience taught them about whether voice is worth the effort?”

3. The status protector: preserving face and reputation

At the executive level reputation is currency. Difficult conversations often threaten what sociologists call Face which is a person’s public self image.

Brown and Levinson’s politeness theory (1987) posits that direct criticism is a “face threatening act.” For a senior leader admitting a mistake or engaging in a conversation that implies failure can feel like a direct withdrawal from their bank of political capital. In high visibility roles leaders are often performing confidence even when they feel doubt. To drop that mask feels like a loss of authority. Their deflection is not an accident. It is a sophisticated strategy to save face designed to maintain social standing and authority. In this context agreement is not about alignment. It is about performance art designed to keep their status intact.

The leadership task You must lower the identity threat before you can address the performance challenge.

- Use permission based entry: Give them agency before the dive. Ask “Can I raise something that might feel uncomfortable but could materially improve our outcome?” Permission reduces the feeling of attack.

- Frame the issue as shared risk: Move the spotlight from their performance to collective reputation. Ask “If this continues how does this reflect on us six months from now?” This turns avoidance from a safety strategy into a liability.

The core shift: They are not hiding the truth. They are managing how they are seen. Your influence grows when you allow dignity to be protected while truth is spoken.

4. The harmoniser: when conflict is emotionally expensive

For some conflict is not just politically risky but physiologically draining.

Personality research specifically the Big Five model shows that individuals high in Agreeableness value harmony and cooperation above all else. For these leaders confrontation triggers a high cost in emotional labour (Hochschild, 1983). They have to work significantly harder than others to regulate their own nervous system in the presence of tension. They are often highly empathetic which means they feel the stress of the room acutely. They are not weak. They are temperamentally wired to smooth over friction. When a conversation promises high emotional voltage they naturally default to delay or excessive politeness. This is not cowardice. It is a nervous system response to preserve their own equilibrium.

The leadership task: Your task is to reduce the emotional cost of clarity.

- Introduce structure before emotion: Use written framing or clear options before the meeting. Say “Here are three options with risks and trade offs.” Structure moves the brain from emotional processing to analytical processing.

- Normalise tension: Explicitly name the discomfort so they do not have to. Try “This conversation might feel tense but that is just a sign that the decision matters.” This reframes tension as information rather than danger.

The core shift: Some colleagues are not avoiding responsibility. They are avoiding emotional depletion.

5. The discounter: optimising for short term comfort

Finally there is the cognitive bias of temporal discounting. Humans are wired to value immediate comfort over future benefit.

Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory (1979) and Laibson’s work on hyperbolic discounting (1997) show that we systematically undervalue future risks when faced with immediate pain. Avoiding a difficult conversation today feels like a win because it preserves immediate comfort. The long term cost of misalignment or failure feels abstract and distant. These leaders are effectively taking out a high interest loan on their future peace of mind. They are choosing the smaller immediate reward of a pleasant afternoon over the larger future reward of a solved problem. It is a flaw in human probability processing where the present moment is weighted too heavily against the future.

The leadership task: Your task is to force the future into the present.

- Convert inaction into explicit future cost: Ask “If we avoid this conversation now what is the price we pay in October?” Make the future penalty vivid and immediate.

- Make passive choices visible: Remind them that “Not deciding is also a decision.” By framing avoidance as an active choice with specific consequences you remove the illusion of safety.

The core shift: Avoidance often looks like kindness. In reality it is delayed cost.

Wrapping up

When we work with colleagues who avoid difficult conversations our instinct is often to push harder. We try to force courage or demand accountability. But behavioural science teaches us that trying to change a person’s personality is the slowest and least effective way to change an organisation.

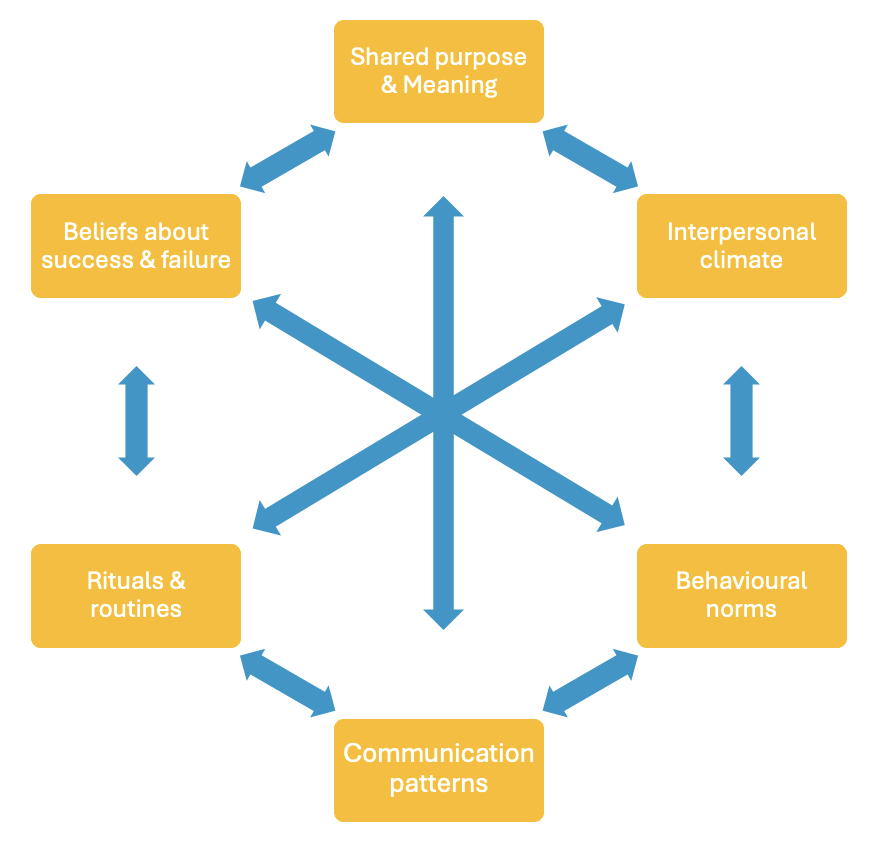

The more effective path is to change the environment in which that person is operating. Resistance is rarely about stubbornness. It is about a mismatch between the behaviour you want and the incentives the brain perceives. Your leverage as a leader lies in your ability to diagnose the specific barrier your colleague is facing.

- Is it Safety? (Reduce the risk)

- Is it Futility? (Show the impact)

- Is it Face? (Protect their dignity)

- Is it Emotion? (Add structure)

- Is it Time? (Reveal the future cost)

When you stop treating silence as a character flaw and start treating it as a signal about the quality of the conversation, you shift from being a critic to being an architect. You design a space where honesty is not just possible but rational. That is when the real work begins.

Additional reading

How to deal with passive aggressive behaviour at work Passive aggressive behaviour is costly. This guide explores why ambiguity is used as a weapon and offers five evidence based moves to interrupt the spiral of incivility. It focuses on regulating your reaction and naming behaviour without diagnosing the person.

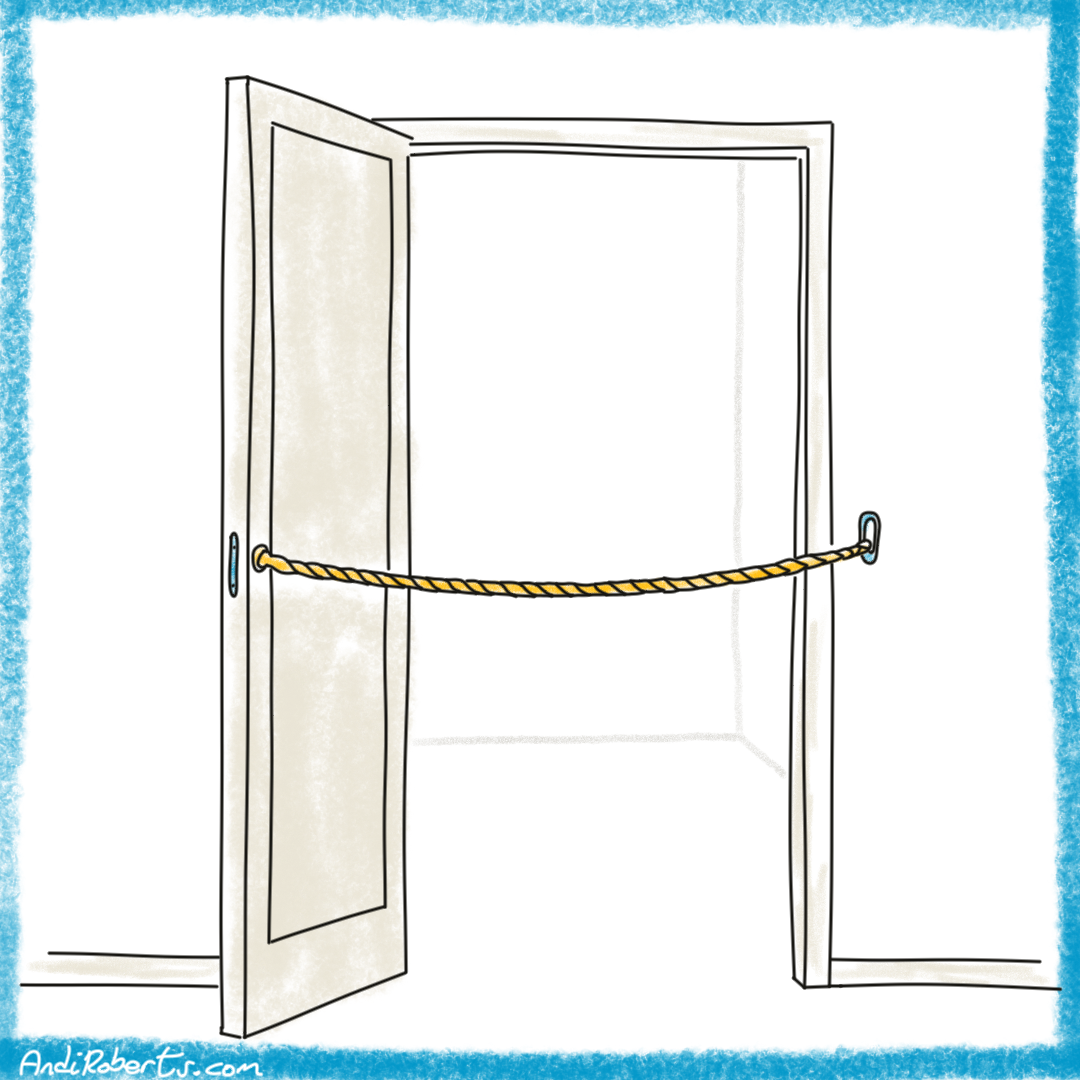

How to influence others without manipulating them Influence is an invitation rather than an imposition. This article introduces five specific doors of influence including Rationalising, Asserting and Inspiring. It helps leaders identify which style they over rely on and which they neglect.

Why people agree in public but resist change in private Most change initiatives fail because of false agreement. This piece examines the psychological drivers behind the nodding head phenomenon such as social safety and loss aversion. It offers strategies to shift teams from compliance to ownership.

The self expression realm of emotional intelligence Self expression bridges internal feeling and external action. This breakdown of the EQ model explores how emotional expression, assertiveness and independence work together. It is essential for leaders who struggle to stand their ground without aggression.

The interpersonal realm of emotional intelligence Leadership is an act of relationship. This overview covers the three capacities of the interpersonal realm which are interpersonal relationships, empathy and social responsibility. It explores how to build the trust that sustains performance.

The leadership skills library A comprehensive resource of over 100 leadership capabilities. Each entry includes definitions, barriers and enablers. Relevant tabs for this topic include Accountability, Conflict management, Managerial courage and Feedback.

Do you have any tips or advice for engaging with those who do not engage?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Sources:

Brown, P. and Levinson, S.C. (1987) Politeness: some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Costa, P.T. and McCrae, R.R. (1992) Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Edmondson, A. (1999) ‘Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp. 350–383.

Hochschild, A.R. (1983) The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) ‘Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk’, Econometrica, 47(2), pp. 263–291.

Laibson, D. (1997) ‘Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), pp. 443–477.

Morrison, E.W. and Milliken, F.J. (2000) ‘Organizational silence: a barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world’, Academy of Management Review, 25(4), pp. 706–725.

VitalSmarts (2010) Cost of conflict: why silence is killing your bottom line. Provo, UT: VitalSmarts.

Leave A Comment