Most organisational change does not fail because people openly resist it.

It fails because people agree in public and disengage in private.

Heads nod in meetings, commitments are made in town halls, and follow-up emails are full of polite affirmation. Then, quietly, behaviour does not change. Old practices persist. New processes are delayed. Energy drains from the system without visible conflict. Leaders often describe this as “lack of buy-in” or “change fatigue”, yet behavioural research shows that something deeper and more predictable is occurring.

Gartner’s large-scale change research found that only 34 per cent of employees are truly engaged in supporting organisational change initiatives, even when more than 70 per cent express positive attitudes towards those same initiatives (Gartner, 2016). Public agreement is therefore a poor indicator of genuine commitment.

Neuroscience research helps explain why this pattern is so persistent. Functional MRI studies have shown that social rejection and the risk of exclusion activate the same neural pathways as physical pain, particularly within the anterior cingulate cortex (Eisenberger and Lieberman, 2004). Disagreeing with a dominant group narrative therefore feels neurologically unsafe, even in psychologically mature and well-intentioned workplaces. Public agreement becomes a protective behaviour rather than an expression of belief.

At the same time, behavioural economics demonstrates that people experience potential losses far more intensely than equivalent gains. Kahneman and Tversky’s foundational work on prospect theory showed that losses are weighted roughly twice as heavily as gains in human decision-making (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). Organisational change, however positively framed, inevitably carries perceived losses relating to competence, status, routines, control and identity. These losses are often unspoken yet deeply felt, and they silently shape behaviour long after public commitments have been made.

This combination of social safety seeking and loss aversion creates a perfect environment for false agreement. People are not being disingenuous. They are being adaptive. They choose safety, stability and identity protection in ways that allow them to appear cooperative while preserving personal equilibrium. The result is a form of organisational politeness that feels harmonious on the surface yet quietly erodes execution beneath it.

Traditional change management approaches unintentionally amplify this problem. Communication campaigns focus on building awareness and explaining the rationale for change. Engagement surveys reward visible positivity. Leaders, under pressure to demonstrate momentum, often interpret dissent as resistance to be corrected rather than information to be learned from. In doing so, organisations inadvertently teach people that agreement is safe and doubt is dangerous. The system becomes fluent in the language of support while behaviour remains unchanged.

The question therefore is not why people resist change. It is why they comply without committing. Understanding this distinction is central to leading meaningful transformation. Real change does not begin when people understand what is happening. It begins when they feel psychologically safe enough to tell the truth about what the change costs them, threatens in them and requires from them. Until that truth becomes discussable, public agreement will continue to mask private resistance, and leaders will continue to mistake politeness for progress.

What is really happening beneath polite agreement

When people publicly support change and privately resist it, leaders often interpret this as cynicism, apathy or lack of accountability. Behavioural science suggests a different explanation. What appears as disengagement is more accurately understood as a rational protective response to perceived psychological and social risk. Beneath polite agreement, three predictable dynamics are almost always present.

The first is the primacy of social safety over truth. Human beings are neurologically wired to preserve belonging because social connection has been central to survival throughout evolutionary history. Modern neuroscience has demonstrated that social threat is processed by the brain as real danger. Eisenberger, Lieberman and Williams showed that experiences of social exclusion activate the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula, the same regions associated with physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003). This means that speaking against a dominant narrative in a group does not merely feel uncomfortable. It feels unsafe at a biological level. In organisational settings, this manifests as reluctance to voice doubt, raise concerns or challenge strategic direction, particularly when senior leaders are present. Public agreement therefore becomes a self-protective behaviour. It preserves social standing, avoids reputational risk and reduces the possibility of being perceived as negative, difficult or disloyal. People choose safety over candour, not because they lack integrity, but because their nervous system is seeking protection.

The second dynamic is loss aversion, which quietly dominates decision-making long after a change has been intellectually accepted. Prospect theory demonstrates that potential losses are experienced as significantly more powerful than equivalent gains (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). In the context of organisational change, leaders tend to focus communication on opportunity, improvement and future benefit. Employees, however, experience change through the lens of what might be taken away. This includes the loss of competence as familiar tasks are replaced, the loss of status as roles are redefined, the loss of autonomy as new systems introduce controls, and the loss of predictability as routines are disrupted. These losses are rarely named openly, yet they exert a stronger influence on behaviour than any promised benefit. Public agreement allows people to avoid conflict while privately slowing down, delaying or selectively complying in order to protect what still feels secure.

The third dynamic is identity threat. Work is not simply a set of tasks. It is a primary source of meaning, social position and self-definition. Research in social identity theory demonstrates that when aspects of identity are threatened, people respond defensively even in the absence of conscious awareness (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Organisational change can unintentionally send messages such as your previous way of working is no longer valued, your expertise is becoming obsolete, or your contribution matters less in the future state. These messages may not be explicitly stated, yet they are often felt. When identity is threatened, people rarely argue. They withdraw. They disengage quietly. They comply superficially while withholding full participation in order to preserve a sense of dignity and self-worth.

Together, these three forces create the conditions for false agreement to flourish. Polite compliance becomes a survival strategy. People maintain social belonging, protect themselves from perceived loss, and defend their identity without ever having to openly resist. From the outside, the organisation appears aligned. Underneath, energy leaks away through quiet non-adoption, selective engagement and passive delay.

Understanding these dynamics is essential because it reframes the leadership task. False agreement is not a behavioural failure to be corrected. It is a signal that the change conversation is happening in a way that does not yet feel safe, balanced or human enough for people to tell the truth. Until those underlying psychological forces are addressed, no amount of additional communication, training or accountability will produce genuine commitment.

Why traditional change management unintentionally makes this worse

Most organisational change efforts are built on a well-intended but flawed assumption, that if people understand the case for change, they will naturally commit to it. Considerable investment is therefore made in communication plans, roadshows, slide decks, FAQs and engagement surveys, all designed to explain why the change is necessary, urgent and beneficial. These approaches are rational, logical and carefully structured. Behavioural science shows, however, that they often deepen the very resistance they are trying to remove.

Understanding creates awareness, but awareness does not create ownership. Decades of research into attitude–behaviour gaps demonstrate that people can hold positive attitudes towards an initiative while failing to change their behaviour in practice. A meta-analysis of 47 studies found that intentions explain only around 28 per cent of actual behaviour, with the majority of behavioural variance driven by situational, emotional and social factors rather than rational belief (Sheeran, 2002). In other words, people can genuinely agree that a change is sensible, necessary and beneficial, and still not enact it.

Traditional change programmes also tend to unintentionally signal that dissent is undesirable. Leaders often present a unified narrative of certainty, clarity and confidence in order to inspire trust. While well meaning, this can make doubt feel like disloyalty. Engagement surveys typically reward positivity, optimism and alignment, reinforcing the idea that support is the correct response. Over time, organisations become fluent in the language of affirmation. People learn what to say. They do not necessarily change what they do.

Power dynamics further amplify this effect. Research on authority gradients demonstrates that individuals are significantly less likely to challenge or question those in senior positions, even when they hold relevant information or concerns (Milgram, 1963; Edmondson, 2018). In change settings, this means that critical insights about feasibility, workload, risk and unintended consequences often remain unspoken. Leaders receive compliance signals rather than learning signals, and private resistance becomes the only available outlet for unexpressed doubt.

Formal change management also tends to emphasise speed, momentum and visible progress. Milestones, traffic-light dashboards and adoption metrics encourage leaders to look for evidence that the organisation is “on board”. These systems unintentionally reward surface-level compliance. People focus on appearing aligned rather than working through what the change truly requires of them. Quiet resistance is therefore not a failure of discipline. It is a rational adaptation to an environment where disagreement feels unsafe and uncertainty is unwelcome.

The result is a subtle but powerful distortion. Leaders believe they are managing change. In reality, they are managing agreement. The system becomes skilled at producing the appearance of alignment while the deeper work of commitment remains undone. Energy is spent on presentation rather than participation. The organisation moves forward on paper while behaviour remains anchored in the past.

This is the moment where many change efforts quietly stall. Not because people are incapable, but because the design of the change conversation has not yet created the conditions for ownership. To lead real change, leaders must move beyond selling, explaining and reassuring. They must begin to redesign the conversation itself.

The real leadership task, shifting from compliance to ownership

When change efforts stall beneath polite agreement, leaders often respond by increasing communication, tightening accountability and reinforcing expectations. These actions are logical, yet they address the surface of the problem rather than its source. The real issue is not whether people understand what is being asked of them. It is whether they experience themselves as participants in the change or as recipients of it. This distinction determines whether behaviour follows.

Ownership is fundamentally different from compliance. Compliance is transactional. It is driven by obligation, surveillance and the avoidance of negative consequence. Ownership is relational. It is driven by meaning, agency and belonging. Behavioural science shows that these two states activate different motivational systems within the brain. Self-determination theory, one of the most extensively validated motivational frameworks in psychology, demonstrates that people sustain effort and change behaviour most reliably when three psychological needs are met, autonomy, competence and relatedness (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

When these needs are undermined, people may still comply, but they do not commit.

Most organisational change unintentionally erodes all three. Autonomy is reduced as new processes prescribe how work must be done. Competence is threatened as familiar skills become less central. Relatedness becomes conditional as support is subtly linked to positivity and visible alignment. The result is not open rebellion but quiet withdrawal. People protect themselves by doing the minimum required while withholding discretionary energy, creativity and initiative.

Peter Block describes this pattern as the difference between treating people as consumers of change and inviting them into citizenship. Consumers wait to be served. Citizens take responsibility for what they create together. Behavioural research supports this distinction. Studies on participative decision-making show that when individuals are involved in shaping decisions that affect their work, both commitment and performance increase significantly, even when the final outcome is not their preferred option (Somech, 2002). Participation does not simply create satisfaction. It creates psychological ownership.

False agreement therefore becomes a diagnostic signal rather than a failure. It indicates that the change has not yet become something people can author, influence or shape. It is still something being done to them rather than created with them. Until that shifts, no amount of communication or enforcement will produce genuine engagement.

This reframes the leadership task. The role of the leader is not to persuade people to accept the change. It is to create the conditions in which people can take responsibility for it. This requires a different kind of conversation, one that moves away from selling certainty and towards inviting participation. It requires leaders to trade control for contribution, and performance for partnership.

Real change begins when people stop asking, “What do you want us to do?” and start asking, “What are we willing to take responsibility for together?” That question marks the moment when polite agreement can finally begin to turn into real commitment.

The five strategies that convert false agreement into real commitment

Once leaders recognise that false agreement is a signal of missing ownership rather than missing understanding, the question shifts from persuasion to participation. The task is no longer to convince people to accept the change, but to redesign the conversations and conditions through which people can become authors of what is being created.

Together, the five strategies that follow form a coherent leadership model for converting surface alignment into genuine ownership. Each one addresses a different psychological barrier that sustains polite compliance and quiet resistance. Collectively, they restore autonomy, dignity and belonging to the centre of change leadership. When these conditions are present, commitment begins to replace compliance and behaviour begins to follow.

1. Replace selling with asking

One of the most reliable ways to deepen private resistance is to try harder to sell the change. When leaders respond to slow adoption with more presentations, stronger narratives and greater emphasis on benefits, they often trigger a predictable psychological reaction. Human beings have a fundamental need to preserve autonomy. When people feel that their behaviour is being directed or engineered, they instinctively protect their sense of agency by withdrawing commitment. This reaction is known in behavioural psychology as psychological reactance, the motivational state that arises when individuals perceive that their freedom to choose is being threatened (Brehm, 1966). Even well-intended persuasion can therefore produce the opposite of its desired effect.

In organisational change, this dynamic is subtle but powerful. Leaders increase communication in order to build alignment. Employees experience this as pressure. They may continue to express agreement, yet privately disengage in order to preserve a sense of independence and self-determination. The more the change is sold, the less people feel that it belongs to them.

The antidote to this is not softer selling. It is a different form of conversation altogether. Ownership begins when people are invited into authorship rather than asked for acceptance. Questions, when asked genuinely, return agency to the system. They shift people from defending their position to participating in the creation of what comes next.

Research on participatory change processes demonstrates that involvement in shaping decisions significantly increases commitment, even when the final decisions are constrained by organisational realities (Lines, 2004). What matters is not that people get their preferred outcome, but that they experience themselves as contributors rather than recipients.

This requires leaders to replace explanation with inquiry. Instead of asking whether people understand the change, leaders can ask what the change makes harder, what feels uncertain, what might be underestimated, and what would make the change worth personal investment. These questions invite people to surface private concerns in ways that feel legitimate and safe. They also generate information that leaders cannot obtain through formal reporting.

Asking rather than selling changes the psychological contract. It signals that people are trusted to think, not just to comply. It restores autonomy, reduces hidden resistance and begins to transform the change from a mandate into a shared endeavour.

2. Make doubt visible and respectable

False agreement thrives in environments where doubt is privately felt but publicly unsafe. Most organisations unintentionally create such environments by equating positivity with professionalism and certainty with leadership. In doing so, they remove the only socially acceptable channel through which people can express concern, ambiguity or disagreement. What remains is silence, followed by quiet non-adoption.

Psychological safety research demonstrates that when people do not feel safe to speak openly, they do not stop thinking critically. They simply stop sharing what they know. Edmondson’s research shows that teams with low psychological safety report fewer problems, not because fewer problems exist, but because fewer problems are voiced (Edmondson, 2018). The system therefore becomes progressively less informed while appearing more aligned.

Large group dialogue processes offer a practical remedy to this dynamic. Methods such as Open Space Technology were designed precisely to surface what is present but unspoken within a system. Harrison Owen observed that when people are given real freedom to name what matters to them, the conversations that emerge almost always reveal the issues that formal agendas avoid. These are not side conversations. They are the real change conversations.

What makes these processes powerful is not their informality, but their design logic. They create conditions in which autonomy is restored, hierarchy is softened, and peer-to-peer truth telling becomes socially safe. Behavioural research supports this design. Studies on participative dialogue show that when individuals are invited to define the agenda, their sense of psychological ownership increases significantly, which in turn predicts higher levels of commitment and follow-through (Pierce, Kostova and Dirks, 2001).

Doubt, when surfaced in such settings, stops being a threat to momentum and becomes a resource for learning. Questions about feasibility, workload, unintended consequences and role clarity are no longer experienced as resistance, but as contributions to the quality of the change itself.

Leaders who wish to convert polite agreement into real commitment must therefore stop treating doubt as a problem to be solved and begin treating it as information that must be hosted. This does not require the adoption of any particular methodology. It requires the creation of spaces where people can speak about what is difficult, what is uncertain and what feels risky without being judged or corrected.

Until doubt becomes visible and respectable, public agreement will continue to mask private resistance. When doubt is welcomed, however, the system begins to move from performance to participation, and from compliance to ownership.

3. Name the losses, not just the gains

Most organisational change narratives are constructed around improvement. They focus on what will be better, faster, simpler or more competitive in the future state. While these narratives are strategically sound, they unintentionally obscure a critical psychological reality. Every meaningful change carries loss. When losses are not named, they are not removed. They are simply carried privately.

Behavioural research consistently shows that people cannot fully engage in a new future while they are quietly grieving an unacknowledged past. Loss aversion, first articulated by Kahneman and Tversky, demonstrates that losses are experienced as significantly more emotionally powerful than gains (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). In organisational change, these losses are rarely dramatic, yet they are deeply personal. They include the loss of routines that provided rhythm to the working day, the loss of competence that came from being skilled in familiar systems, the loss of informal influence that came with knowing how things really worked, and the loss of identity tied to being experienced, reliable and trusted.

When leaders speak only of opportunity, they unintentionally invalidate these losses. People learn that there is no safe place to talk about what they are giving up. They therefore protect themselves quietly by slowing adoption, selectively engaging and keeping emotional distance from the change. This behaviour is often mislabelled as resistance, when it is more accurately understood as unresolved grief.

Psychological research on transition shows that acknowledgement of loss is a prerequisite for adaptation. Bridges’ work on transition theory demonstrates that people must psychologically disengage from the old before they can meaningfully engage with the new (Bridges, 2004). Skipping this phase does not speed change. It delays it.

Leaders who wish to convert public agreement into private commitment must therefore begin naming what is being lost, not only what is being gained. This requires courage because it introduces emotional truth into strategic conversation. It invites people to speak about what they will miss, what will become harder, and what parts of their professional identity feel threatened.

When losses are acknowledged, people experience themselves as seen rather than managed. This recognition restores dignity and allows emotional energy to be released rather than suppressed. Only then can people begin to invest fully in building what comes next.

Naming loss is not a sentimental exercise. It is a strategic act. It clears the emotional ground on which real commitment can grow.

4. Create small acts of choice

Commitment is not created through belief alone. It is built through behaviour. People begin to feel ownership of a change not when they agree with it, but when they take part in shaping it through visible action. This is why small, meaningful acts of choice are so powerful. They convert abstract endorsement into lived participation.

Behavioural science demonstrates that when individuals experience even limited choice, their sense of agency increases significantly. Research on self-determination shows that perceived autonomy is a primary driver of sustained motivation and behavioural persistence (Deci and Ryan, 2000). When change is introduced in highly prescribed ways, autonomy is reduced and people protect themselves by disengaging quietly. When people are invited to make choices, even within constraints, they begin to re-enter the change as authors rather than subjects.

These choices do not need to be grand or strategic. In fact, small choices are often more effective because they are immediately actionable and psychologically accessible. Allowing teams to decide where to pilot new practices, what legacy activities to stop in order to create capacity, how to sequence adoption, and how to adapt processes to local realities restores a sense of influence. These choices communicate that people are trusted to shape how the change becomes real in their context.

Behavioural research on the foot-in-the-door effect shows that small initial acts of participation significantly increase the likelihood of larger future commitments (Freedman and Fraser, 1966). When people take even modest ownership actions, they begin to align their identity with the change. They move from seeing it as an external initiative to seeing it as something they are part of creating.

Small acts of choice also surface practical insight. They reveal obstacles, resource constraints and unintended consequences that formal planning often overlooks. Leaders gain real data while people gain real agency.

When choice is absent, false agreement persists because there is no behavioural pathway through which ownership can grow. When choice is present, commitment becomes visible, measurable and self-reinforcing.

This is the moment where change starts to feel real, not because it is mandated, but because people have begun to shape it with their own hands.

5. Shift accountability from compliance to contribution

Most organisational accountability systems are designed to measure compliance. They ask whether people are aligned, whether milestones have been met, and whether required actions have been completed. While necessary for operational control, these measures are poorly suited to generating genuine commitment. They reward visible conformity rather than meaningful participation. In environments where false agreement is already present, this emphasis unintentionally deepens disengagement by teaching people how to look compliant without becoming invested.

Behavioural research shows that accountability framed around obligation activates extrinsic motivation, which is effective for short-term compliance but weak for sustained behavioural change (Deci, Koestner and Ryan, 1999). When people are primarily motivated by external pressure, they do what is required and little more. Discretionary effort, innovation and resilience decline because these behaviours require intrinsic commitment.

Contribution-based accountability reframes participation from obedience to ownership. Instead of asking whether people are aligned, leaders ask what individuals and teams are willing to take responsibility for creating. Instead of tracking whether instructions have been followed, leaders track what people have chosen to contribute to the success of the change. This shift restores agency and reinforces identity as a contributor rather than a subordinate.

Research on psychological ownership shows that when individuals feel that a change initiative is partly “theirs”, they demonstrate higher levels of care, persistence and initiative (Pierce, Kostova and Dirks, 2001). This sense of ownership is created not through formal assignment, but through voluntary commitment to specific contributions.

In practice, this means asking different questions in meetings, reviews and one-to-one conversations. Leaders can ask what people are willing to commit to, what support they need to fulfil those commitments, and what they have learned through trying. These conversations invite people to define their own participation and to take responsibility for their part in the collective outcome.

Contribution-based accountability also makes disengagement visible in healthy ways. It is easier to notice when people are not choosing to contribute than when they are quietly complying. This creates opportunities for honest dialogue about capacity, confidence, clarity and readiness rather than defaulting to blame.

When accountability is reframed around contribution, false agreement loses its hiding place. People either step into authorship or surface what is holding them back. Both outcomes strengthen the change.

Conclusion – The deeper truth about leading change

People do not resist change. They resist being changed without having a voice in what they are becoming. What looks like disengagement is often a quiet form of self-protection in environments that feel emotionally unsafe, identity-threatening or autonomy-reducing. False agreement is therefore not a failure of character. It is a signal about the quality of the conversation taking place.

Behavioural science shows that sustained change depends less on communication and more on agency, dignity and belonging. When people experience themselves as recipients of change, they comply on the surface and withdraw beneath it. When they experience themselves as contributors, commitment begins to grow.

This reframes the role of leadership. The leader’s task is not to sell certainty, but to design conversations in which people can speak honestly, influence what is being created and choose what they are willing to contribute. Change accelerates not when leaders push harder, but when people are invited into authorship of the future they are being asked to inhabit.

Real change begins when ownership replaces compliance.

Self-reflection questions

- Where in your organisation might people be agreeing publicly while disengaging privately, and what might this be signalling about the safety of your change conversations.

- What losses might people be experiencing because of your current change agenda that have not yet been named or acknowledged.

- What genuine choices and contributions could you invite from people that would allow them to become authors rather than recipients of this change.

Further reading & resources

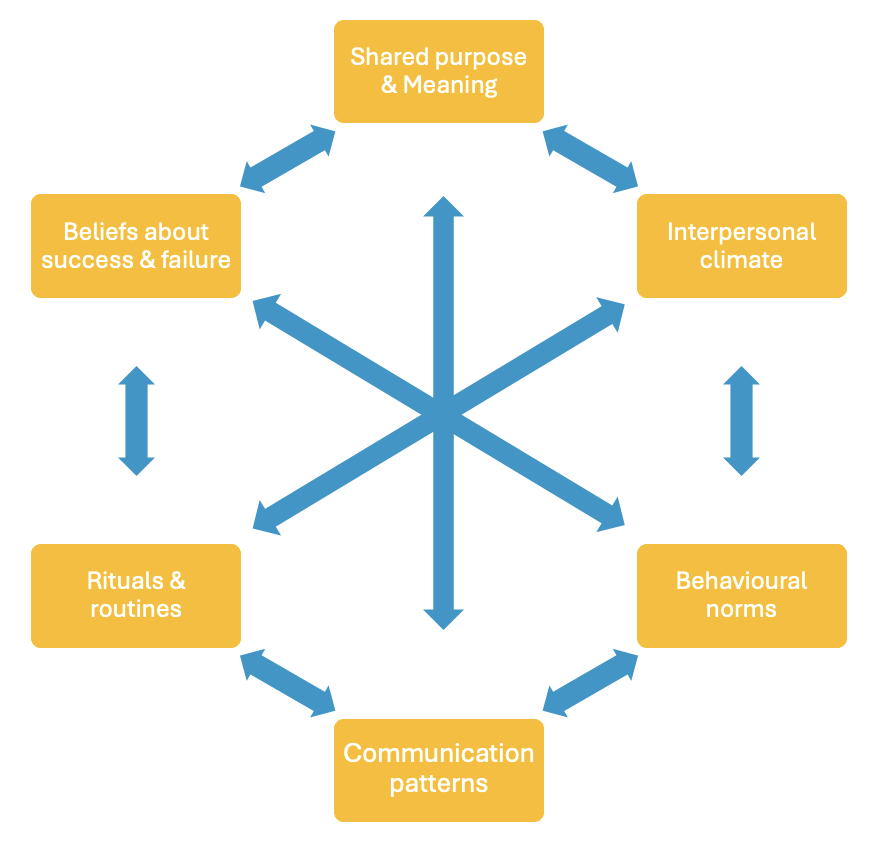

How can I create a positive climate for organisational change? Change cannot take root in a toxic environment. This article explores the six specific leadership behaviors, from clarity to fairness, that build the psychological climate necessary for transformation to succeed.

Debunking the leadership myth that people do not like change A deeper dive into why “resistance” is often a rational response to loss, confusion, and bad design. This piece challenges the standard narrative and offers a more human centered view of adaptation.

How can I get change to stick? (BJ Fogg’s B=MAP) Using BJ Fogg’s behavioral science framework, this guide explains why relying on motivation alone fails and how to design “ability” and “prompts” to make new behaviors automatic.

How do I rebuild trust and resilience in my team after constant change? When teams are exhausted from constant restructuring, standard change management isn’t enough. Learn the four resilience behaviors (Candour, Resourcefulness, Compassion, Humility) that restore stability.

Everyday Habits for Transforming Systems (Adam Kahane Summary) A practical summary of Adam Kahane’s approach to systems change, focusing on how small, everyday habits like “working with the cracks” can shift complex systems from the inside out.

OpenSpace Beta: A guide to 90-day transformation For leaders looking for a radical alternative to slow change programs. This sketchnote summary outlines how to use large group dialogue (Open Space Technology) to flip an organization from command and control to self organization in just three months.

Do you have any tips or advice for helping people engage with change?

What has worked for you?

Do you have any recommended resources to explore?

Thanks for reading!

Sources:

- Beer, M., Eisenstat, R.A. and Spector, B. (1990) ‘Why change programs don’t produce change’, Harvard Business Review, November–December.

- Brehm, J.W. (1966) A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Bridges, W. (2004) Transitions: Making sense of life’s changes. 2nd edn. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (2000) ‘The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour’, Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), pp. 227–268.

- Deci, E.L., Koestner, R. and Ryan, R.M. (1999) ‘A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation’, Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), pp. 627–668.

- Edmondson, A.C. (2018) The fearless organisation: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Eisenberger, N.I. and Lieberman, M.D. (2004) ‘Why rejection hurts: A common neural alarm system for physical and social pain’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(7), pp. 294–300.

- Eisenberger, N.I., Lieberman, M.D. and Williams, K.D. (2003) ‘Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion’, Science, 302(5643), pp. 290–292.

- Freedman, J.L. and Fraser, S.C. (1966) ‘Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(2), pp. 195–202.

- Gartner (2016) Engaging employees in change. Stamford, CT: Gartner Research.

- Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) ‘Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk’, Econometrica, 47(2), pp. 263–291.

- Kotter, J.P. (1995) ‘Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail’, Harvard Business Review, March–April.

- Lines, R. (2004) ‘Influence of participation in strategic change: Resistance, organisational commitment and change goal achievement’, Journal of Change Management, 4(3), pp. 193–215.

- Milgram, S. (1963) ‘Behavioral study of obedience’, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), pp. 371–378.

- Pierce, J.L., Kostova, T. and Dirks, K.T. (2001) ‘Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organisations’, Academy of Management Review, 26(2), pp. 298–310.

- Sheeran, P. (2002) ‘Intention–behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review’, European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), pp. 1–36.

- Somech, A. (2002) ‘Explicating the complexity of participative management: An investigation of multiple dimensions’, Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(3), pp. 341–371.

- Tajfel, H. and Turner, J.C. (1979) ‘An integrative theory of intergroup conflict’, in Austin, W.G. and Worchel, S. (eds.) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–47.

Leave A Comment